Published online May 16, 2020. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v12.i5.149

Peer-review started: March 27, 2020

First decision: April 29, 2020

Revised: May 6, 2020

Accepted: May 12, 2020

Article in press: May 12, 2020

Published online: May 16, 2020

Processing time: 49 Days and 12 Hours

A recent expert panel issued recommendations about the technical aspects of direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) for pancreatic walled-off necrosis (WON). However, significant technical heterogeneity still exists among endoscopists.

To report the outcomes of our DEN technique and how it differs from a recent expert consensus statement and previous studies.

Medical records of patients with WON who underwent DEN from September 2016 - May 2019 were queried for the following information: Age, gender, ethnicity, etiology of acute pancreatitis, WON location and size, DEN technical information, adverse events (AEs) and outcomes. Adverse events were graded according to the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Lexicon grading system. Technical success was defined as adequate lumen apposing metal stent (LAMS) deployment plus removal of ≥ 90% of necrosum. Clinical success was defined as complete resolution of WON cavity by imaging and resolution of symptoms at ≤ 3 months (mo) after last DEN. Data analysis was performed using mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, frequency and proportion for categorical variables, and median and range for interval data.

A total of 21 patients underwent DEN. Most of them were Hispanic and their mean age was 51 ± 17 years. The majority of the collections were located in the body of the pancreas and the mean size was 13 cm ± 5 cm. The most common indication was persistent vomiting. Antibiotics were administered only in cases of infected necrosis. All LAMS were placed without radiological guidance, dilated the same day of deployment and removed after a mean of 27 ± 11 d. Routine cross-sectional imaging immediately after drainage was not performed. The mean interval between DEN sessions was 7 ± 4 d and the mean number of DEN/patient was 3 ± 2. Technical and clinical success rates were both 95%. AEs were seen in 5 patients and included: Sepsis (2), stent migration (1), stent maldeployment (1), perforation (1). The sensitivity and positive predictive value of an occluded LAMS leading to sepsis was 50% and 0.11 respectively. No fatalities were observed.

Our DEN technique differed significantly from the one recommended by a recent expert panel and the one published in previous studies. Despite these differences excellent clinical outcomes were obtained.

Core tip: Currently, the most commonly accepted treatment for pancreatic walled-off necrosis is direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN). Despite recent recommendations by an international expert panel, no endoscopic technique and/or device has been adopted as a gold standard, and significant technical heterogeneity exists among endoscopists. In this study we provide a detailed description of the procedure including endoscopes and devices used; as well as how our technique differs from international recommendations and previous publications on the topic. In a predominantly Hispanic population, our DEN technique achieved excellent clinical outcomes.

- Citation: Mendoza Ladd A, Bashashati M, Contreras A, Umeanaeto O, Robles A. Endoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy in the United States-Mexico border: A cross sectional study. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 12(5): 149-158

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v12/i5/149.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v12.i5.149

Pancreatic walled-off necrosis (WON) remains a common complication of necrotizing pancreatitis that significantly impairs patients’ quality of life by any of the following: Persistent abdominal pain, infection, gastric outlet obstruction or enteral feeding intolerance. Endoscopic drainage with direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) has slowly replaced surgical necrosectomy due to its minimally invasive nature and superior clinical outcomes[1,2].

Although DEN is currently considered a standard procedure, the technical aspects of it vary widely among endoscopists and institutions. Currently, no official practice guidelines exist for DEN and several technical questions remain unanswered. In this study we provide an in-depth description of our DEN technique, its outcomes and how it differs from recent recommendations by an international expert panel and other previously published studies.

A retrospective medical record review was performed on a cohort of patients who underwent DEN for the management of WON at our interventional endoscopy unit from August 1, 2016 to June 31, 2019. The following information was recorded: Subject demographics, size and location of WON, indication for drainage; number, duration and frequency of DEN; device(s) and endoscope(s) used, clinical outcomes and adverse events (AEs).

Technical success was defined as correct placement of the lumen apposing metal stent (LAMS) between the cavity and the gastric/duodenal lumen, plus removal of ≥ 90% of necrosum. Clinical success was defined as complete resolution of the WON cavity by imaging and of patient’s symptoms at follow-up ≤ 3 mo after last DEN. Adverse events were graded according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy lexicon severity grading system[3]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for human research of our institution. Data analysis was performed using mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, frequency and proportion for categorical variables and median and range for interval data. A statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

A total of 21 patients underwent DEN during the study period and their demographic information is summarized in (Table 1). The majority were Hispanic males with a mean age of 51 ± 17. The most common etiology of acute pancreatitis was gallstone disease.

| Characteristics | n = 21 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 15 (71.4) |

| Female | 6 (28.6) |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 51 ± 16.9 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Hispanic | 16 (76.2) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 5 (23.8) |

| Etiology of pancreatitis, n (%) | |

| Biliary | 17 (81.0) |

| Alcohol | 3 (14.3) |

| Idiopathic | 1 (4.7) |

| Location of WON, n (%) | |

| Body | 17 (81.0) |

| Entire pancreas | 2 (9.5) |

| Head | 1 (4.7) |

| Tail | 1 (4.7) |

| WON dimension, mean ± SD, cm | 13.4 ± 5.0 |

| Indication for DEN, n (%)1 | |

| Persistent vomiting | 14 (66.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (61.9) |

| Infection/sepsis | 6 (28.6) |

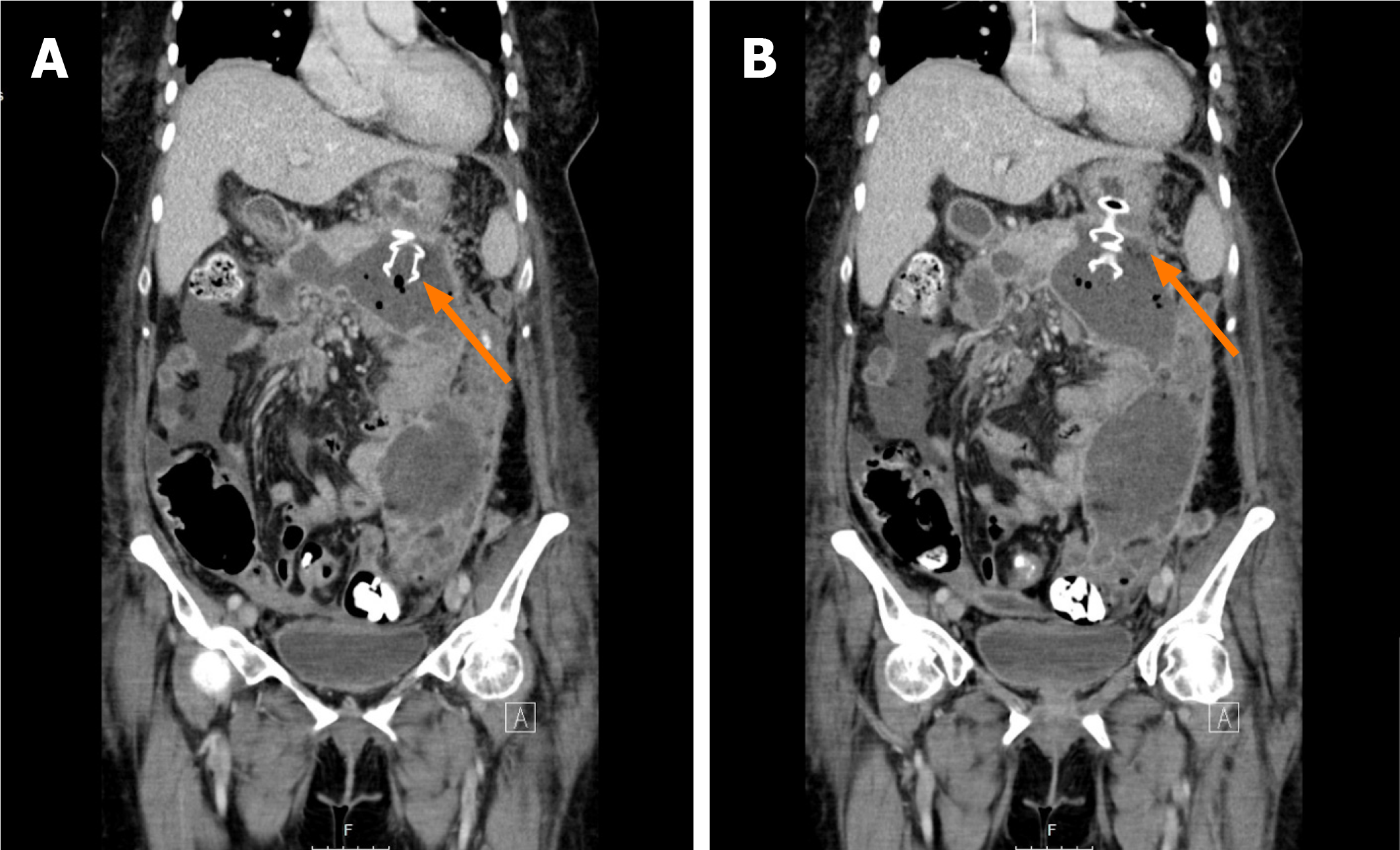

The mean size of the WON cavities was 13 cm ± 5 cm, and the majority of them were located in the body of the pancreas. The three main indications for drainage were persistent vomiting, abdominal pain, and infection. In some patients the indications overlapped.

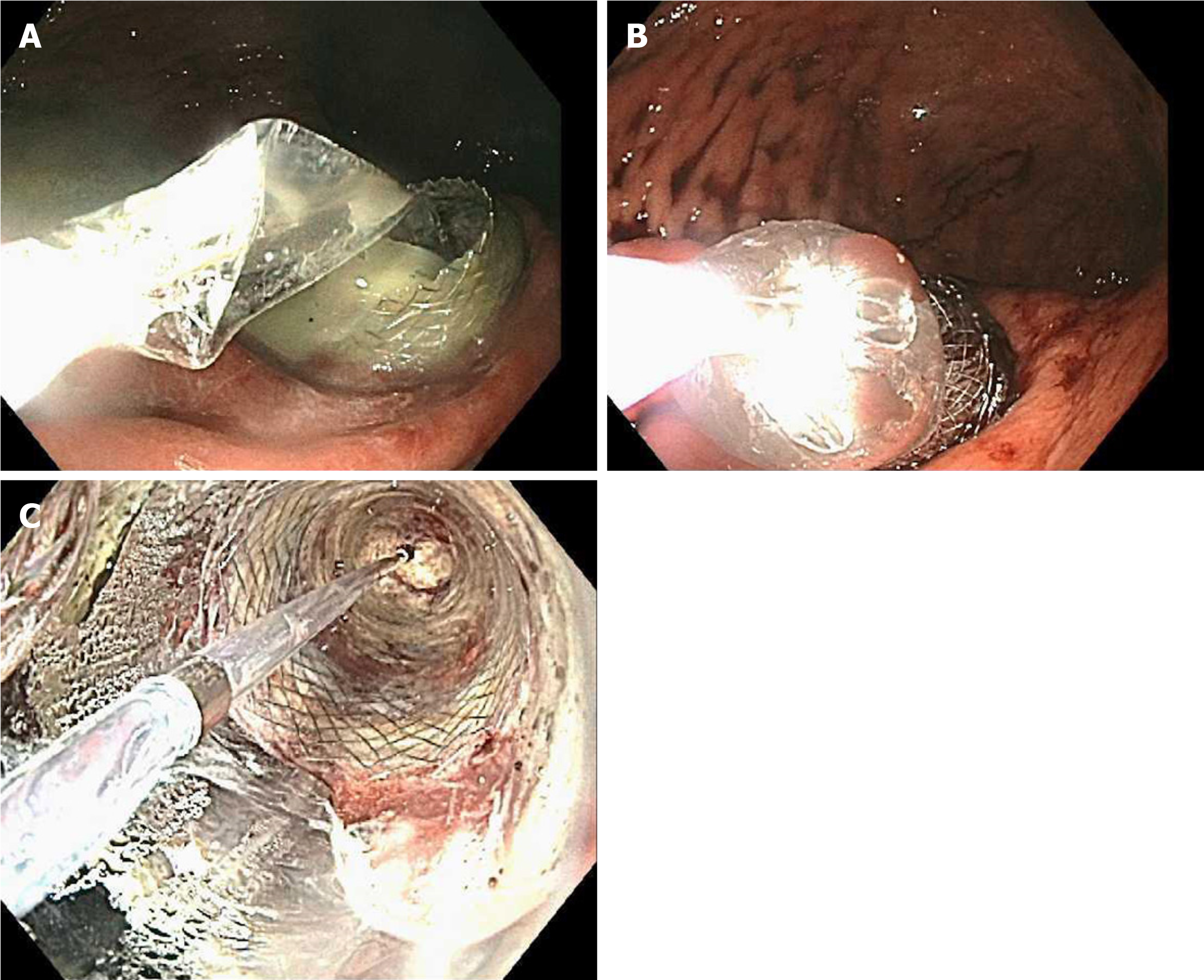

A total of 24 LAMS were placed in 21 patients (one patient required 3 LAMS and another one 2). Twenty-three were placed through the stomach and one through the duodenum. All the procedures were performed under general anesthesia by two experienced interventional endoscopists. Only the patients who presented with infected necrosis received antibiotic therapy prior to drainage as part of their standard of care treatment. In all cases the cavity was drained with an electrocautery enhanced 10 mm × 15 mm AXIOS™ Stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass) using the GF-UCT180 or the TGF-UC180J forward-viewing curvilinear array ultrasound gastrovideoscopes (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The first flange of the LAMS was deployed under sonographic guidance and the second one under endoscopic guidance (Figure 1). Fluoroscopy was not used to guide placement of the stent. All LAMS were dilated the same day of deployment to 15 mm using the distal 2 cm of a 12-13.5-15 mm wire guided esophageal CRE balloon dilation catheter (Boston scientific, Natick, MA, United States). Dilation was performed sequentially from 12 to 13.5 and finally to 15 mm. (Figure 2).

The mean interval from LAMS placement to first DEN was 5 ± 4 d. A total of 66 DEN sessions were performed and the mean number of DEN/patient was 3 ± 2. Each DEN was repeated every 7 ± 4 d, and the average duration of each session was 50 ± 29 min. All patients were kept on a regular diet for the entire duration of their treatment and were especially instructed to avoid all kinds of seeds until the stent was removed. The EVIS EXERA III (GIF-HQ190) video gastroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used in all cases. However, in 11 cases (17%), the EVIS EXERA II (GIF-2TH180) was also used. The 27 mm CaptiflexTM snare (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) was the most commonly used device for debridement (94%). Others included the HistolockTM resection device, the RaptorTM forceps, the TalonTM grasping device (US endoscopy, Mentor OH); the 2 cm Trapezoid™ RX Wireguided Retrieval Basket as well as the 12-15 mm and 15-18 mm Extractor™ Pro retrieval balloon catheters (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States). In some patients more than one device was used (Table 2). Immediately after each DEN the cavity was irrigated with 60 cc of a 1:1 solution of sterile water plus hydrogen peroxide at 3%. Necrosectomy was repeated until the endoscopist determined that ≥ 90% of necrosum had been removed (Figure 3). At that point a cross-sectional imaging study was obtained to evaluate the collection. If the result was favorable, the LAMS was then removed using the RaptorTM forceps (Figure 4) at a subsequent session. All LAMS were removed after a mean interval of 27 ± 11 d.

| LAMS | n = 24 |

| Trans-gastric, n (%) | 23 (96) |

| Body, n (%) | 17 (74) |

| Antrum, n (%) | 3 (13) |

| Cardia, n (%) | 1 (4.3) |

| Incisura, n (%) | 1 (4.3) |

| Pre-pyloric, n (%) | 1 (4.3) |

| Trans-duodenal | 1 (4) |

| Dilated same day, n (%) | 24 (100) |

| Placement to retrieval, mean ± SD, d | 27.2 (10.6) |

| DEN | n = 66 |

| DEN/patient, mean ± SD | 3.1 ± 2.2 |

| LAMS placement to first DEN, mean ± SD, d | 5.4 ± 4.4 |

| DEN duration, mean ± SD, min | 49.9 ± 28.9 |

| DEN interval, mean ± SD, d | 6.9 ± 4.1 |

| Endoscope n (%)1 | |

| EVIS EXERA III (GIF-HQ190) | 66 (100) |

| EVIS EXERA II (GIF-2TH180) | 11 (16.7) |

| Endoscpic device n (%)2 | |

| 27 mm Captiflex Snare | 62 (93.9) |

| Trapezoid RX Wireguided Retrieval Basket | 9 (13.6) |

| Raptor Forceps | 4 (6.1) |

| Roth Net Platinum Retriever | 4 (6.1) |

| Extractor Pro Balloon | 3 (4.5) |

| Single-Use Radial Jaw 4 Forceps | 2 (3.0) |

| Talon Grasping Device | 1 (1.5) |

Technical success was achieved in 20/21 patients (95%). Clinical success was achieved in 18/19 patients (95%). Two patients were lost to follow-up. No recurrences were observed after a median follow-up of 24 mo (range 10-38).

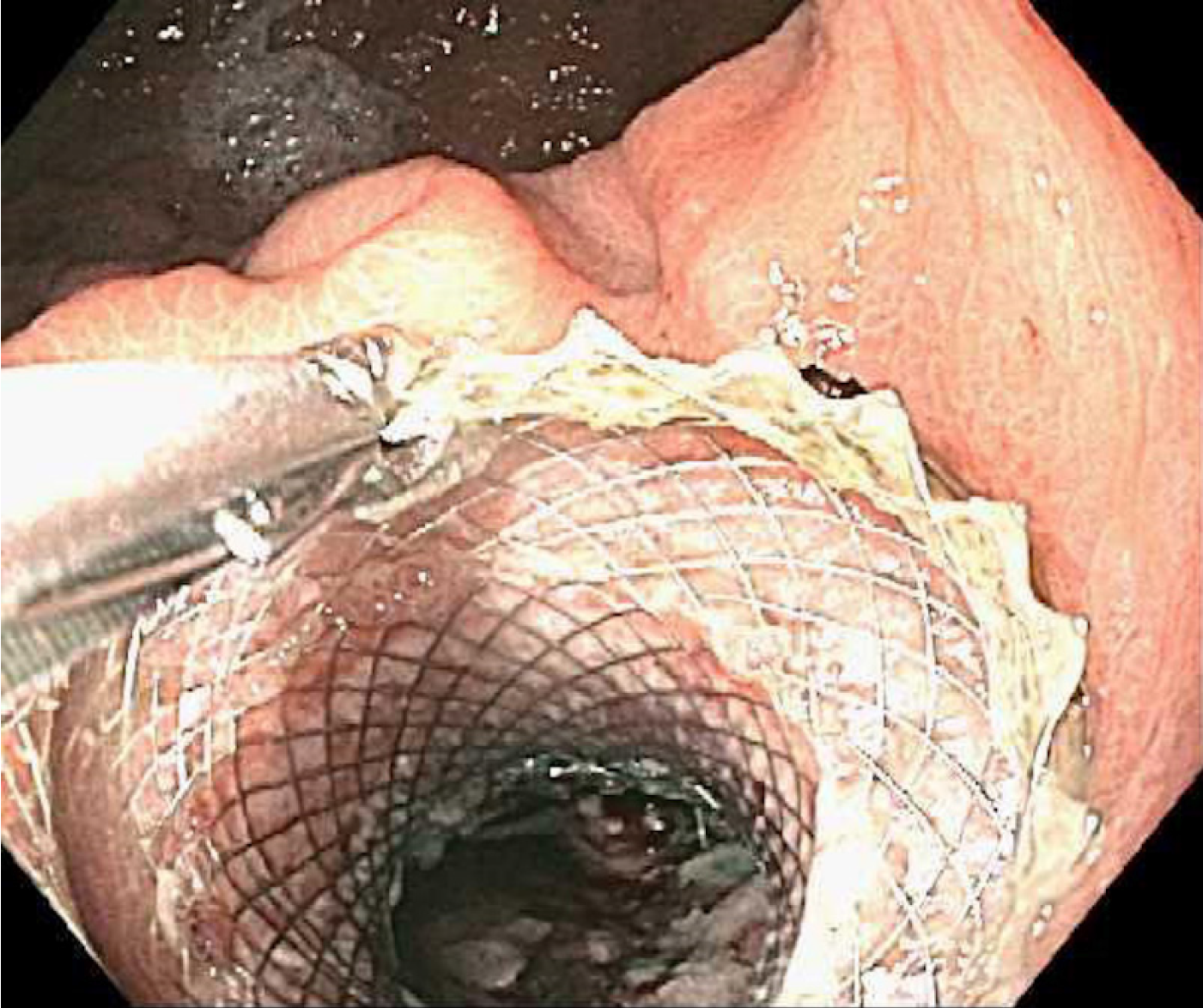

A total of 5 patients developed AE’s but only one of them was severe. No fatalities occurred (Table 3). Two patients developed sepsis within two weeks after initial LAMS placement. Emergent DEN was performed in both and complete occlusion of the LAMS was found in 1 of them. One of these patients required an unexpected LAMS exchange at a subsequent DEN session due to its entanglement with the debridement device; and a subsequent third LAMS at week 4 to complete treatment. In a third patient, the LAMS was accidentally misplaced inside the collection. To avoid further complications, it was left inside the collection and a new one was then successfully placed through the original puncture site (Figure 5). The second LAMS was then dilated, and DEN was performed as usual. Both stents were removed 4 wk later. A fourth patient had a full stent migration. A computed tomography of the abdomen could not identify the stent, confirming spontaneous passage. A fifth patient experienced a WON cavity wall rupture during DEN. He developed severe abdominal pain immediately after the procedure and required surgical intervention. He recovered completely.

| Subject | Complication | Severity grade1 | Treatment |

| 3 | Stent misplaced inside the collection | Mild | New stent placed through the same tract. Both stents removed after 4 wk. |

| 4 | Sepsis and entanglement of grasping device with the stent | Mild, Moderate | IV antibiotics and emergent DEN. Stent removed, and 2 more stents placed. |

| 5 | Cavity wall rupture | Severe | Exploratory laparotomy and IV antibiotics. |

| 11 | Stent migration | Mild | No treatment. Stent could not be found. |

| 15 | Sepsis | Mild | IV antibiotics and emergent DEN. |

Since the first report of endoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy with plastic stents[4], significant improvements have been made to the procedure. In 2005 Seewald et al[5] introduced the concept of dilating the puncture site to introduce an endoscope and perform DEN. In 2009, the use of a fully covered esophageal self-expandable metal stent was described by Sarkaria et al[6] and Antillon et al[7]. With the advent of LAMS, DEN evolved from a complicated and time consuming procedure, to a relatively simple one with excellent clinical outcomes in adequately trained hands[8-13]. As a result, DEN is now the preferred method for the management of WON in most centers around the world.

Although the procedure is now accepted as standard, its technique is not. One reason for this technical heterogeneity is the lack of specialized equipment. The development of debriding devices has lagged behind the one of those used to access the collection. Hence, a variety of devices are currently used for debridement: Biliary sweeping balloons, snares, lithotripsy baskets, rat tooth forceps and nets. This gap in specialized debriding equipment adds unnecessary risks to a procedure with a current AE rate of 3%-16%[9-11,13-16]. In an attempt to minimize AE, new devices have been tested[17,18], but none of them is ready for prime time.

Another reason is the lack of evidence either supporting or opposing the different technical aspects of the procedure. In light of this heterogeneity, a consensus by a panel of experts was recently published[19]. Seven aspects of the procedure were addressed, but strong agreement was reached in only 3 of them: (1) Drainage of WON with LAMS should be the standard of care; (2) The ideal diameter of the LAMS should be ≥ 15 mm; and (3) DEN should not be performed the same day of LAMS placement. No consensus was achieved on whether the LAMS should be dilated on the same day of deployment or not, the adequate timing for obtaining follow up cross-sectional imaging or for removing the LAMS, and the utility of nasocystic drains.

All DEN in this study were performed with the EVIS EXERA III GIF-HQ190 video gastroscope but occasionally the EVIS EXERA II GIF-2TH180 was also used. The 2nd operative channel in this endoscope, allowed the simultaneous introduction of two devices to assist in debridement (i.e., 2 snares) or keep potent suction while using a single device. Using this endoscope requires extra caution since its diameter is 12.6 mm, as opposed to the 9.9 mm of the EVIS EXERA III GIF-HQ190. Introducing a 12.6 mm endoscope through the 15 mm LAMS, paired with simultaneous use of 2 debriding devices through the endoscope may increase the risk of stent dislodgement.

The most reliable device for debridement was the snare. Large snares like the 27 mm CaptiflexTM were preferred but smaller ones such as the HistolockTM were also used. Other devices such as the RaptorTM forceps, the Extractor™ Pro retrieval balloon catheters, the Talon™ grasping device and the 2 cm Trapezoid™ RX Wireguided Retrieval Basket were used as well but the success rate with any of them was disappointingly low. In one case, the Talon™ grasping device got entangled with the LAMS during DEN and forced its removal. Difficulty determining the exact direction in which its prongs open during DEN makes this device suboptimal for debridement and prone to complications. Therefore, after this incident the device was not further used.

The most common indications for DEN were abdominal pain and persistent nausea/vomiting. Interestingly, infected WON was not as common as it has been in previous studies[11-14]. The reason(s) for this is/are unknown. Whether the incidence of infected WON is lower in Hispanics, should be investigated further. Despite the lack of agreement by the recent international expert panel regarding dilating the LAMS immediately after deployment; we dilated all of them to their maximum diameter the same day without complications. Since perforation has been reported during dilation of the LAMS[15], only the distal 2 cm of the balloon were introduced through its lumen. This prevented the tip of the balloon catheter to come in contact with the distal wall of the cavity, minimizing perforation risk.

The mean number of DEN sessions/patient was in concordance with that reported in some studies;[9,11,16] although others have reported fewer sessions[10,14]. This variation is a reflection of the different outcome definitions and the type of stent(s) utilized. Since none of these previous studies included removal of ≥ 90% of necrosum in their technical success definition, we expected a greater number of DEN sessions/patient. However, this was not the case. Interestingly our clinical outcomes were not different than those in studies in which such aggressive debridement was not required[9-13,15,17]. This finding suggests that complete debridement of the WON cavity may not be necessary to achieve adequate results.

Although the AE’s encountered in this study were similar to the ones reported in the literature[8-11,13], some deserve further discussion. Despite the common assumption that LAMS occlusion leads to infection, our findings did not support this notion. Two patients developed sepsis after initial drainage, and only one had an occluded LAMS. Of the 19 patients who did not develop sepsis, 8 (42%) had a completely occluded LAMS at some point during their treatment. Therefore, despite the lack of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to drainage, the sensitivity and positive predictive value of an occluded stent leading to sepsis was 50% and 0.11, respectively. This findings question the need for routine antibiotic prophylaxis when performing this procedure.

Regarding LAMS migration, previous studies have reported a rate of 0%-13%. It is important to understand that in these studies the LAMS have remained in place for an average of 8 wk and double pig tail plastic stents have been placed across its lumen to prevent migration[9,10,12,13,16]. Our migration rate was 5% despite not using such stents and removing the LAMS after a mean interval of only 4 wk. These findings suggest that LAMS migration is not related to any of these two factors. However, whether migration rate increases beyond 8 wk, remains unknown due to lack of data.

Due to our excellent clinical outcomes we developed our own institutional DEN protocol (Table 4). The major differences between our protocol, the recent recommendations and other published studies include: Lack of routine antibiotic prophylaxis prior to drainage, dilation of the LAMS the same day of deployment, aggressive debridement (≥ 90% of necrosum needs to be removed), lack of radiological imaging to guide the LAMS placement or immediately after it and finally, interval for LAMS removal.

| Perform all procedures under general anesthesia to protect the patient’s airway. Do not administer routine antibiotic prophylaxis except in patients undergoing treatment of infected necrosis. |

| Access the cavity with the AXIOS™ Stent and Electrocautery Enhanced Delivery System either through a GF-UCT180 curvilinear array ultrasound gastrovideoscope, or the TGF-UC180J forward-viewing curvilinear array ultrasound gastrovideoscope. Trans-gastric access is preferred, but if no safe window is found, trans-duodenal access is acceptable. |

| Deploy and dilate the LAMS on the same session. Dilation should be made with the distal 2 cm of the 12-13.5-15 mm CRE balloon dilation catheters in a sequential manner holding each diameter for 1 min until the maximum of 15 mm is achieved. |

| Perform the first DEN ≥ 1 wk after initial drainage and repeat weekly until the cavity is free of necrosum. Infuse 60 cc of 3% H2O2 into the cavity at the end of each DEN. Extending each DEN for > 1 h is not recommended. |

| Perform DEN with the EVIS EXERA III GIF-HQ190 or the II GIF-2TH180 video gastroscopes. If the 2TH180 is used, caution needs to be exercised as passing this endoscope through the LAMS may increase the risk of dislodgement. |

| Perform debridement with metal snares such as the CaptiflexTM or the HistolockTM. Avoid using other devices, especially those with open prongs as these may get entangled with the LAMS and force stent removal. |

| Obtain cross-sectional imaging once the cavity is free of necrosum and preparations are being made for stent removal (unless any acute adverse events are suspected before that). |

| Once the cavity is clean, remove the LAMS with a rat tooth forceps. |

This study has the following strengths. It is the first to describe outcomes in Hispanic patients, a constantly underrepresented minority in the literature. It also highlights the fact that deviations from the recommendations by an international expert panel still obtain excellent clinical outcomes. Finally, it provides an in-depth description of the technical aspects, types of endoscopes and devices used during the procedure. On the other hand, the main limitations include its relatively small sample size, retrospective design and the fact that the data comes from a single center in the United States.

In conclusion, despite its limitations this study proves that DEN is a procedure in which technical diversity within acceptable limits does not compromise clinical outcomes. Prospective multicenter randomized trials addressing topics such as the optimal interval for LAMS removal, the role of prophylactic antibiotics, cross-sectional imaging and complete debridement of the cavity are needed.

Currently, no official practice guidelines exist for direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN). A recent international expert panel issued recommendations about some of its technical aspects, but they are not universally applied by endoscopists worldwide.

To demonstrate that in DEN, flexibility within acceptable limits does not compromise outcomes.

To describe how our DEN technique differs from recent expert panel recommendations and other previously published studies. To provide an in-depth overview of our DEN technique with detailed description of endoscopes and devices used, as well as of its clinical outcomes and adverse events.

Retrospective review of medical records of patients with walled-off necrosis (WON) who underwent DEN. Technical success was defined as adequate lumen apposing metal stent (LAMS) deployment plus removal of ≥ 90% of necrosum. Clinical success was defined as complete resolution of WON cavity by imaging and of symptoms at ≤ 3 mo after last DEN. Data analysis was performed using mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, frequency and proportion for categorical variables, and median and range for interval data.

Data was collected on 21 patients. The mean age was 51 ± 17 years. The majority of patients were Hispanic and most of the collections were located in the body of the pancreas. Antibiotics were administered only in cases of infected necrosis. All LAMS were placed without radiological guidance, dilated the same day of deployment and removed after a mean of 27 ± 11 d. Routine cross-sectional imaging immediately after drainage was not performed. The mean number of DEN/patient was 3 ± 2. Technical and clinical success rates were both 95%. Two patients were lost to follow-up. Five patients experienced adverse events, but none were fatal.

This study showed that endoscopic management of pancreatic WON is a procedure in which technical diversity within acceptable limits does not compromise clinical outcomes. It suggests that antibiotic prophylaxis and complete debridement are not necessary; and that stent occlusion is not unequivocally associated to sepsis.

Prospective multicenter randomized trials addressing topics such as the optimal interval for LAMS removal, the role of prophylactic antibiotics, cross-sectional imaging and complete debridement of the cavity are needed.

The authors would like to thank the entire endoscopy staff for their assistance - in particular, Veronica Davitt, RN.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (136083); American College of Gastroenterology (35849).

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shi H S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Hazebroek EJ, Nijmeijer RM, Poley JW, van Ramshorst B, Vleggaar FP, Boermeester MA, Gooszen HG, Weusten BL, Timmer R; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tan V, Charachon A, Lescot T, Chafaï N, Le Baleur Y, Delchier JC, Paye F. Endoscopic transgastric versus surgical necrosectomy in infected pancreatic necrosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:770-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Nemcek A, Petersen BT, Petrini JL, Pike IM, Rabeneck L, Romagnuolo J, Vargo JJ. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1238] [Cited by in RCA: 1835] [Article Influence: 122.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Baron TH, Thaggard WG, Morgan DE, Stanley RJ. Endoscopic therapy for organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:755-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Seewald S, Groth S, Omar S, Imazu H, Seitz U, de Weerth A, Soetikno R, Zhong Y, Sriram PV, Ponnudurai R, Sikka S, Thonke F, Soehendra N. Aggressive endoscopic therapy for pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess: a new safe and effective treatment algorithm (videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:92-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarkaria S, Sethi A, Rondon C, Lieberman M, Srinivasan I, Weaver K, Turner BG, Sundararajan S, Berlin D, Gaidhane M, Rolshud D, Widmer J, Kahaleh M. Pancreatic necrosectomy using covered esophageal stents: a novel approach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:145-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Antillon MR, Bechtold ML, Bartalos CR, Marshall JB. Transgastric endoscopic necrosectomy with temporary metallic esophageal stent placement for the treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:178-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rinninella E, Kunda R, Dollhopf M, Sanchez-Yague A, Will U, Tarantino I, Gornals Soler J, Ullrich S, Meining A, Esteban JM, Enz T, Vanbiervliet G, Vleggaar F, Attili F, Larghi A. EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections using a novel lumen-apposing metal stent on an electrocautery-enhanced delivery system: a large retrospective study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1039-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Siddiqui AA, Adler DG, Nieto J, Shah JN, Binmoeller KF, Kane S, Yan L, Laique SN, Kowalski T, Loren DE, Taylor LJ, Munigala S, Bhat YM. EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections and necrosis by using a novel lumen-apposing stent: a large retrospective, multicenter U.S. experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:699-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Yan L, Dargan A, Nieto J, Shariaha RZ, Binmoeller KF, Adler DG, DeSimone M, Berzin T, Swahney M, Draganov PV, Yang DJ, Diehl DL, Wang L, Ghulab A, Butt N, Siddiqui AA. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy at the time of transmural stent placement results in earlier resolution of complex walled-off pancreatic necrosis: Results from a large multicenter United States trial. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:172-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sharaiha RZ, Tyberg A, Khashab MA, Kumta NA, Karia K, Nieto J, Siddiqui UD, Waxman I, Joshi V, Benias PC, Darwin P, DiMaio CJ, Mulder CJ, Friedland S, Forcione DG, Sejpal DV, Gonda TA, Gress FG, Gaidhane M, Koons A, DeFilippis EM, Salgado S, Weaver KR, Poneros JM, Sethi A, Ho S, Kumbhari V, Singh VK, Tieu AH, Parra V, Likhitsup A, Womeldorph C, Casey B, Jonnalagadda SS, Desai AP, Carr-Locke DL, Kahaleh M, Siddiqui AA. Endoscopic Therapy With Lumen-apposing Metal Stents Is Safe and Effective for Patients With Pancreatic Walled-off Necrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1797-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chandran S, Efthymiou M, Kaffes A, Chen JW, Kwan V, Murray M, Williams D, Nguyen NQ, Tam W, Welch C, Chong A, Gupta S, Devereaux B, Tagkalidis P, Parker F, Vaughan R. Management of pancreatic collections with a novel endoscopically placed fully covered self-expandable metal stent: a national experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:127-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Bapaye A, Itoi T, Kongkam P, Dubale N, Mukai S. New fully covered large-bore wide-flare removable metal stent for drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: results of a multicenter study. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thompson CC, Kumar N, Slattery J, Clancy TE, Ryan MB, Ryou M, Swanson RS, Banks PA, Conwell DL. A standardized method for endoscopic necrosectomy improves complication and mortality rates. Pancreatology. 2016;16:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rimbaș M, Rizzati G, Gasbarrini A, Costamagna G, Larghi A. Endoscopic necrosectomy through a lumen-apposing metal stent resulting in perforation: is it time to develop dedicated accessories? Endoscopy. 2018;50:79-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Siddiqui AA, Kowalski TE, Loren DE, Khalid A, Soomro A, Mazhar SM, Isby L, Kahaleh M, Karia K, Yoo J, Ofosu A, Ng B, Sharaiha RZ. Fully covered self-expanding metal stents versus lumen-apposing fully covered self-expanding metal stent versus plastic stents for endoscopic drainage of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: clinical outcomes and success. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:758-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bazarbashi AN, Ge PS, de Moura DTH, Thompson CC. A novel endoscopic morcellator device to facilitate direct necrosectomy of solid walled-off necrosis. Endoscopy. 2019;51:E396-E397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Vyas N, Sachdev M, Das A, Khosravi F. Pancreatic necrosectomy using an automated mechanical endoscopic tissue extraction device. VideoGIE. 2018;3:354-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Guo J, Saftoiu A, Vilmann P, Fusaroli P, Giovannini M, Mishra G, Rana SS, Ho S, Poley JW, Ang TL, Kalaitzakis E, Siddiqui AA, De La Mora-Levy JG, Lakhtakia S, Bhutani MS, Sharma M, Mukai S, Garg PK, Lee LS, Vila JJ, Artifon E, Adler DG, Sun S. A multi-institutional consensus on how to perform endoscopic ultrasound-guided peri-pancreatic fluid collection drainage and endoscopic necrosectomy. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:285-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |