Published online Jan 16, 2020. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v12.i1.33

Peer-review started: June 26, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: August 9, 2019

Accepted: November 18, 2019

Article in press: November 18, 2019

Published online: January 16, 2020

Processing time: 178 Days and 1.4 Hours

The ingestion of foreign bodies (FBs) and food bolus impaction (FBI) in the digestive tract are commonly encountered clinical problems. Methods to handle such problems continue to evolve offering advantages, such as the avoidance of surgery, reduced cost, improved visualization, reduced morbidity, and high removal success rate. However, to date, no studies have evaluated the endoscopic management of FBs in Japan.

To elucidate level of safety and efficacy in the endoscopic management of FBs and FBI.

A total of 215 procedures were performed at Keio University Hospital between November 2007 and August 2018. Data were collected from medical charts, and endoscopic details were collected from an endoscopic reporting system. Procedures performed with a flexible gastrointestinal endoscope were only taken into account. Patients who underwent a technique involving FB or FBI from the digestive tract were only included. Data on patient sex, patient age, outpatient, inpatient, FB type, FB location, procedure time, procedure type, removal device type, success, and technical complications were reviewed and analyzed retrospectively.

Among the 215 procedures, 136 (63.3%) were performed in old adults (≥ 60 years), 180 (83.7%) procedures were performed in outpatients. The most common type of FBs were press-through-pack (PTP) medications [72 (33.5%) cases], FBI [47 (21.9%)], Anisakis parasite (AP) [41 (19.1%) cases]. Most FBs were located in the esophagus [130 (60.5%) cases] followed by the stomach [68 (31.6%) cases]. AP was commonly found in the stomach [39 (57.4%) cases], and it was removed using biopsy forceps in 97.5% of the cases. The most common FBs according to anatomical location were PTP medications (40%) and dental prostheses (DP) (40%) in the laryngopharynx, PTP (48.5%) in the esophagus, AP (57.4%) in the stomach, DP (37.5%) in the small intestine and video capsule endoscopy device (75%) in the colon. A transparent cap with grasping forceps was the most commonly used device [82 (38.1%) cases]. The success rate of the procedure was 100%, and complication were observed in only one case (0.5%).

Endoscopic management of FBs and FBI in our Hospital is extremely safe and effective.

Core tip: The present study highlights the level of efficacy and safety in the removal of foreign bodies in Japan, using different devices avoiding any type of lesion of the digestive tract. Extractions of foreign body using flexible endoscopy were enrolled in the analysis. Press-through-pack medications was the most common FB, as it is commonly used in Japan. We used a large caliber soft oblique cap and grasping forceps and there was no complication in any of the cases. The level of safety and efficacy were excellent, therefore we recommend using devices used in this study.

- Citation: Limpias Kamiya KJ, Hosoe N, Takabayashi K, Hayashi Y, Sun X, Miyanaga R, Fukuhara K, Fukuhara S, Naganuma M, Nakayama A, Kato M, Maehata T, Nakamura R, Ueno K, Sasaki J, Kitagawa Y, Yahagi N, Ogata H, Kanai T. Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies: A retrospective study in Japan. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 12(1): 33-41

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v12/i1/33.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v12.i1.33

The ingestion of foreign bodies (FBs) and food bolus impaction (FBI) are common problems in clinical practice globally. Pre-endoscopic series have shown that ≥ 80% of FBs are likely to pass without requiring intervention, 10%-20% will require non-operative intervention, and ≤ 1% will require surgery[1-6]. The ingestion of FBs mainly occurs in the pediatric population, with a peak incidence between 6 mo and 6 years of age[7]. Among adults, it occurs more commonly in those with psychiatric disorders, alcohol intoxication, and mental retardation and in incarcerated individuals looking for another opportunity to be sent to a medical facility[8]. Edentulous adults are also at risk of the ingestion of FBs, including their own dental prostheses (DP), and FBI[1]. Since the first report in 1972 on the removal of a FB using a flexible endoscope by McKechnie et al[9], this method has continued to evolve owing to its advantages, such as surgery avoidance, reduced cost, accessible technical facilities, visualization improvement, reduced morbidity, and high removal success rate (> 95%)[1,10] as well as the possibility of diagnosis of other diseases. However, to the best of our knowledge, currently, there are no reports on the endoscopic management of FBs and FBIs in Japan.

The present observational study was conducted at the Center for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopy of Keio University Hospital and was approved by the ethics committee of Keio University Hospital (approval ID 20180281). The study included the data of patients with a history of FB ingestion or FBI who underwent endoscopic therapy at Keio University Hospital between November 2007 and August 2018. Data were collected from medical records, and endoscopic details were collected through an endoscopic reporting system (Solemio ENDO, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Only procedures performed with a flexible gastrointestinal endoscope were considered. Additionally, only patients who underwent a technique involving FBs or FBI removal from the digestive tract were included. Patients who underwent a technique involving pushing of the FBI into the stomach without posterior removal were excluded. The following data were extracted: (1) Sex; (2) Age; (3) Outpatient or inpatient; (4) FB type; (5) FB location (laryngopharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, or colon); (6) FB type according to anatomical location; (7) Procedure time; (8) Procedure type [esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy (CS), or single-balloon enteroscopy (SBE)]; (9) Extraction device type; (10) Most used devices according to FB type; and (11) Success and technical complications. According to age, patients were divided into the following four groups: Children (< 15 years old), youth and adults (15-59 years old), old adults (60-79 years old), and very old adults (> 79 years old). FBs that were not very frequent were categorized as “others” (catheters, toothpicks, coins, cotton swabs, packs of illegal drugs, feces, shells, staples, stents, and vinyl). Procedure time was considered as the time required for removal of the FBs or FBI, which was calculated from the insertion of the flexible endoscope to complete extraction of the FB or FBI, including resolution of complications. With regard to the extraction device, we considered all devices used for the removal of the FB or FBI and for the protection of the digestive tract, including devices that were used in combination. Technical complications were considered as complications involving deep laceration, perforation, or bleeding of the mucosa that required additional procedures to achieve hemostasis. In this study, we did not take into account lacerations that showed slight bleeding, in which hemostasis occurred naturally. Procedure success was considered as complete removal of the FB or FBI from the digestive tract, with subsequent confirmation of absence of the FB or FBI on assessment of the digestive tract.

Categorical data are expressed as number and percentage (%), and the procedure duration was calculated as mean with standard deviation (SD) expressed in minutes. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software, version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

A total of 215 procedures were performed between November 2007 and August 2018. Patient background data are presented in Table 1. Of the 215 procedures, 106 (49.3%) were performed in male patients and 109 (50.7%) were performed in female patients. With regard to age, 2 (1%) procedures were performed in children, 77 (36%) were performed in youth and adults, 109 (51%) were performed in old adults, and 27 (12%) were performed in very old adults. Additionally, 180 (83.7%) procedures were performed in outpatients and 35 (16.3%) in inpatients.

| Number of patients (%) | |

| Sex (male/female) | 106 (49.3)/109 (50.7) |

| Age group | |

| < 15 yr | 2 (0.9) |

| 15-59 yr | 77 (35.8) |

| 60-79 yr | 109 (50.7) |

| > 79 yr | 27(12.6) |

| Outpatient/inpatient | 180 (83.7)/35 (16.3) |

Data on FB type are presented in Table 2. In this study, the most common FB was press-trough-pack (PTP) medications [72 (33.5%) cases], followed by FBI [47 (21.9%) cases], Anisakis parasite (AP) [41 (19.1%) cases], DP [23 (10.7%) cases], fish bone [9 (4.2%) cases], endoscopic video capsule device (VCE) [7 (3.3%) cases], spoon [3 (1.4%) cases], and others [13 (6.0%) cases]. On the other hand, the most common location was the esophagus [130 (60.5%) cases], followed by the stomach [68 (31.6%) cases], small intestine [8 (3.7%) cases], laryngopharynx [5 (2.3%) cases], and colon [4 (1.9%) cases].

| Number of patients (%) | |

| Foreign body type | |

| PTP medications | 72 (33.5) |

| Food bolus | 47 (21.9) |

| Anisakis parasite | 41 (19.1) |

| Dental prosthesis | 23 (10.7) |

| Fish bone | 9 (4.2) |

| Video capsule device | 7 (3.3) |

| Spoon | 3 (1.4) |

| Others | 13 (6.0) |

| Location | |

| Laryngopharynx | 5 (2.3) |

| Esophagus | 130 (60.5) |

| Stomach | 68 (31.6) |

| Small intestine | 8 (3.7) |

| Colon | 4 (1.9) |

Data on FB type according to anatomical location are presented in Table 3. The most common FBs according to anatomical location were PTP medications (40%) and DP (40%) in the laryngopharynx, PTP medications (48.5%) and FBI (36.2%) in the esophagus, AP (57.4%) and DP (13.2%) in the stomach, DP (37.5%) and VCE (25%) in the small intestine, and VCE (75%) in the colon.

| Anatomical location | Most common foreign bodies (number/total number) | % |

| Laryngopharynx | PTP (2/5) | 40.0 |

| Dental prosthesis (2/5) | 40.0 | |

| Esophagus | PTP (63/130) | 48.5 |

| Food bolus (47/130) | 36.2 | |

| Stomach | Anisakis parasite (39/68) | 57.4 |

| Dental prosthesis (9/68) | 13.2 | |

| PTP (7/68) | 10.3 | |

| Small intestine | Dental prosthesis (3/8) | 37.5 |

| Video capsule device (2/8) | 25.0 | |

| Colon | Video capsule device (3/4) | 75.0 |

As shown in Table 4, procedure type was dependent on the FB location. The most commonly used procedure was EGD [207 (96.3%) cases], followed by SBE [5 (2.3%) cases] and CS [3 (1.4%) cases]. The procedure times for FB and FBI removal according to location were as follows: Laryngopharynx, 14.2 min (SD 2.7 min); esophagus, 14.5 min (SD 1.1 min); stomach, 14.7 min (SD 1.3 min); small intestine, 31.1 min (SD 1.0 min); and colon, 45.2 min (SD 2.7 min). There was no significant difference in the procedure time across the locations.

| Number of patients (%) | ||

| Procedure type | ||

| EGD | 207 (96.3) | |

| CS | 3 (1.4) | |

| SBE | 5 (2.3) | |

| Procedure time (mean ± SD, min) | ||

| Laryngopharynx | 14.2 ± 2.7 | |

| Esophagus | 14.5 ± 1.1 | |

| Stomach | 14.7 ± 1.3 | |

| Small intestine | 31.1 ± 1.0 | |

| Colon | 45.2 ± 2.7 | |

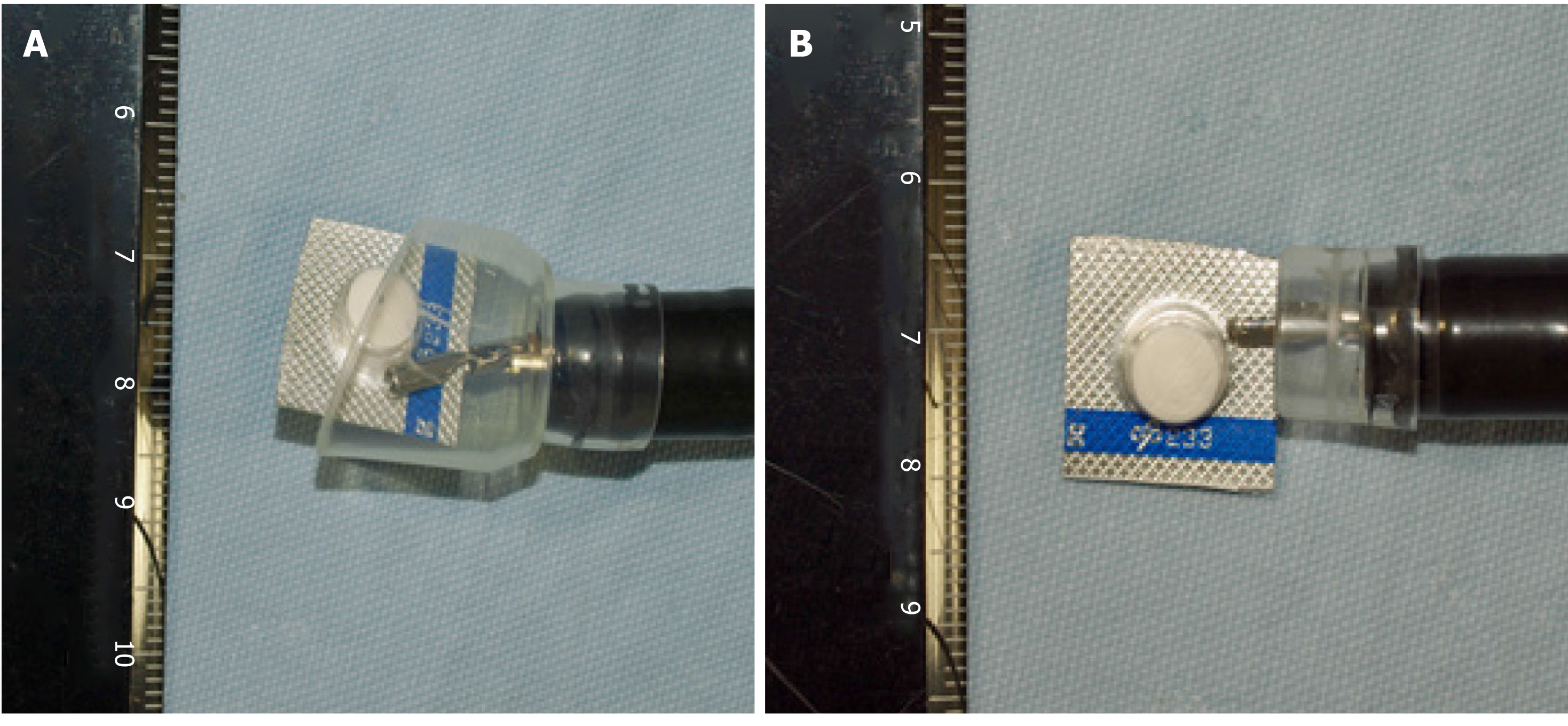

Data on the most used devices according to FB type are presented in Table 5. Different types of devices were used. Devices were used in combination or were used alone. The most common devices according to FB type were a large caliber soft oblique cap with grasping forceps for PTP medications (83.3%) (Figure 1 and Video, grasping forceps for FBI (76.5%), biopsy forceps for AP (97.5%), a large caliber soft oblique cap with grasping forceps for DP (73.9%), a large caliber soft oblique cap with grasping forceps for fish bone (88.8%), a net retriever for VCE (85.7%), and an over-tube with a snare for spoon (66.6%).

| Foreign body type | Device (number/total number) | Percentage (%) |

| PTP | Large caliber transparent cap and grasping forceps (60/72) | 83.3 |

| Food bolus | Grasping forceps (36/47) | 76.5 |

| Anisakis parasite | Biopsy forceps (40/41) | 97.5 |

| Dental prosthesis | Large caliber transparent cap and grasping forceps (17/23) | 73.9 |

| Fish bone | Large caliber transparent cap and grasping forceps (8/9) | 88.8 |

| Capsule device | Net retriever (6/7) | 85.7 |

| Spoon | Over-tube and polypectomy snare (2/3) | 66.6 |

FB removal was successful in all 215 cases (100%), and a complication was noted in only 1 case (0.5%). The complication involved a deep laceration of the mucosa that occurred during DP extraction, and the bleeding was immediately stopped with hemostasis endoclips. There was no need for surgery or re-admission after hospital discharge.

In the present study, most patients were older adults, and this might be because the index of older adults is the highest in the entire Japanese population at present[11]. PTP medications was the most common FB, as it is commonly used in Japan for packaging of medications and is ingested mostly among older adults owing to the use of medications for their different pathologies[12]. Sugawa et al[6] indicated in a review that PTP medications can be removed using a snare net with a protector over-tube or a retractable latex-rubber condom-type hood for mucosal protection. In our study, 83.3% of cases of impaction of PTP medications underwent removal involving a large caliber soft oblique cap and grasping forceps to avoid any damage to the mucosa, and there was no complication in any of the cases. As shown in Figure 1 and Video, a large caliber soft oblique cap can store the PTP medications avoiding mucosal damage, and thus, no complication occurred. A change in the material of PTP medications should be considered to avoid impaction and complications associated with PTP medications ingestion, as it was the most common FB in this study.

FBI was the second most common type of FB (21.9% of cases), and it was noted in the esophagus, which was the anatomical location with the highest incidence in this study. The endoscopic treatment options according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) include in block removal using grasping devices, a piecemeal approach, and advancement of the food bolus into the stomach[1]. Some controversy is present regarding the push technique as there is a perforation risk when applying this technique without first examining the distal esophagus[13]. However, two large studies did not report perforation in a total of 375 patients using the push technique[14,15]. Their approach involved the application of gentle pressure to the center of the food bolus or the reduction of the bolus by piecemeal removal followed by the application of gentle pressure when advancement of the bolus was not successful. It is considered safe to perform dilation after bolus extraction when there is an esophageal stricture in order to avoid recurrence[14,15]. According to previous studies, the push technique is considered as the primary method with a success rate of over 90% and with minimal complications[1,4-6,14,16-19]. The most commonly used technique in our endoscopic center was the piecemeal approach with grasping forceps (76.5% of cases), and there was no complication during or after the extraction. In patients with a suspected etiology of eosinophilic esophagitis, biopsy samples were taken after removal of the FBI, and in patients who presented with an esophageal stricture, balloon dilatation was performed in order to avoid recurrences. The third most common FB in this study was AP (19.1%), and it was commonly located in the stomach. This high percentage might be associated with the fact that in Japan, there is a cultural tradition of eating raw fish in popular dishes, such as sushi and sashimi, which are the main sources of nematodes. According to Tokiwa et al[20], of the 301 cases of food poisoning in Japan between 2013 and 2015, 294 cases involved Anisakis food poisoning, and the most common source of infection was mackerel fish. Opportunities to eat raw fish in sushi bars and Japanese restaurants outside Japan are increasing; therefore, it is important to know about the existence of this parasite and its endoscopic management, as removal is the only approach for symptom relief[21]. In our study, 97.5% of all cases of AP underwent extraction using biopsy forceps, and this approach was successful in all cases without any complications. The fourth most common FB in this study was DP. This FB was common in our study owing to the fact that people using a DP are often old adults or very old adults. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), the ASGE, and Bertoni et al[22] recommend the use of an over-tube as it helps to protect the esophageal and laryngeal mucosa from lacerations. If this protective device is not available, the use of a transparent cap or latex rubber hood is recommended to prevent mucosal injury[3]. In a recent study, Zhang et al[23] recommended the use of a transparent cap to allow a short procedure time and a clear visual field, in addition to mucosal protection. We used a large caliber soft oblique cap in 73.9% of cases. The only complication noted in this study was for DP despite the fact that grip and protection devices for the esophageal mucosa were used. This complication might have been associated with the extended time taken to visit our hospital, which increased the risk of a complication, the fact that the extraction was performed by a beginner endoscopist as our center is a university hospital, the limited working space in the esophagus, or the fact that the rate of complications for sharp-pointed objects is as high as 35%[1]. There were also cases of fish bone impaction and VCE retention, but they were not very frequent. In cases involving fish bone, which is a sharp-pointed object, according to the ASGE and ESGE guidelines and other reports[1-3,22,23], we performed extraction using a large caliber soft oblique cap and grasping forceps in 88.8% of cases, and there were no complications. On the other hand, in the few cases of VCE retention in the small intestine, we successfully used SBE, without any complications. However, double-balloon enteroscopy is also recommended by few reports[1,24,25] There were also some cases of VCE retention in the colon, and the device was removed by conventional CS using a net retriever in almost all cases. This approach was successful in all cases, and there were no complications.

The ASGE and ESGE have stated that only 10%-20% of FB ingestion cases require endoscopic removal[1,3]; however, according to our study, we believe that this percentage might be higher in Japan owing to differences in dietary habits, average population age, and cultural backgrounds between people from Western countries and those from Asian countries, and the most common FBs were sharp-pointed objects that have a higher risk of complications when compared with other types of FBs. Webb et al[10] reported a success rate of 98.8% for endoscopic removal, Li et al[19] reported a success rate of 94.1% in China, and Zhang et al[26] reported a success rate of 96.1% in South China, and most complications involved sharp-pointed objects, similar to our only complication; however, our success rate was 100%.

The present study has some limitations. The study involved a retrospective analysis with a small sample size. There might have been several biases in the current study, such as selection bias associated with the patient enrollment methodology (use of an endoscopic database only). Thus, patients who were expected to have difficulty in endoscopic removal might have directly undergone surgery. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this is the first study to elucidate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic retrieval of FBs and FBI in Japan.

In conclusion, endoscopic management of FBs is extremely safe and effective. The devices used for FB extraction depend on the location and type of FB. As most FBs in our study were sharp-pointed objects, we suggest always placing a large caliber soft oblique cap on the tip of the endoscope and not a straight transparent cap (Figure 1), this will help avoid mucosal injury from the sharp edges during extraction and will provide a clear visual field.

Endoscopic extraction of foreign bodies (FBs) is a method that can present complications depending on the type of management performed.

To date, there are no studies evaluating the endoscopic management of FBs in Japan.

The aim of this study is to elucidate level of safety and efficacy in the endoscopic management of FBs and food boluses in Japan.

This study was a retrospective medical record analysis. A total of 215 procedures were performed at Keio University Hospital between November 2007 and August 2018. Data were collected from medical charts, and endoscopic details were collected from an endoscopic reporting system. Procedures performed with a flexible gastrointestinal endoscope were only taken into account. Patients who underwent a technique involving FB or food bolus removal from the digestive tract were only included. Data on patient sex, patient age, outpatient, inpatient, FB type, FB location, procedure time, procedure type, removal device type, success, and technical complications were reviewed and analyzed retrospectively.

The most common type of FB were press-through-pack (PTP) [72 (33.5%) cases], food bolus [47 (21.9%)], Anisakis parasite (AP) [41 (19.1%) cases]. Most FBs were located in the esophagus [130 (60.5%) cases] followed by the stomach [68 (31.6%) cases]. The most common FBs according to anatomical location were PTP (40%) and dental prostheses (DP) (40%) in the laryngopharynx, PTP (48.5%) in the esophagus, AP (57.4%) in the stomach, DP (37.5%) in the small intestine and video capsule endoscopy device (75%) in the colon. A transparent cap with grasping forceps was the most commonly used device [82 (38.1%) cases]. The success rate of the procedure was 100%, and complication was observed in only one case (0.5%).

Endoscopic management of FBs is extremely safe and effective. The devices used for FB extraction depend on the location and type of FB.

We suggest always placing a large caliber soft oblique cap on the tip of the endoscope and not a straight transparent cap, this will help avoid mucosal injury from the sharp edges during extraction and will provide a clear visual field.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Doyle JJ, Farhat S, Nijhawan S S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher LR, Fukami N, Harrison ME, Jain R, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Maple JT, Sharaf R, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1085-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Birk M, Bauerfeind P, Deprez PH, Häfner M, Hartmann D, Hassan C, Hucl T, Lesur G, Aabakken L, Meining A. Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:489-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ambe P, Weber SA, Schauer M, Knoefel WT. Swallowed foreign bodies in adults. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:869-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ko HH, Enns R. Review of food bolus management. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:805-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sugawa C, Ono H, Taleb M, Lucas CE. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A review. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cheng W, Tam PK. Foreign-body ingestion in children: experience with 1,265 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1472-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nassar E, Yacoub R, Raad D, Hallman J, Novak J. Foreign Body Endoscopy Experience of a University Based Hospital. Gastroenterology Res. 2013;6:4-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McKechnie JC. Gastroscopic removal of a phytobezoar. Gastroenterology. 1972;62:1047-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Miyanaga R, Hosoe N, Naganuma M, Hirata K, Fukuhara S, Nakazato Y, Ojiro K, Iwasaki E, Yahagi N, Ogata H, Kanai T. Complications and outcomes of routine endoscopy in the very elderly. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E224-E229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sudo T, Sueyoshi S, Fujita H, Yamana H, Shirouzu K. Esophageal perforation caused by a press through pack. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16:169-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vizcarrondo FJ, Brady PG, Nord HJ. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:208-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vicari JJ, Johanson JF, Frakes JT. Outcomes of acute esophageal food impaction: success of the push technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:178-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Longstreth GF, Longstreth KJ, Yao JF. Esophageal food impaction: epidemiology and therapy. A retrospective, observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:193-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dray X, Cattan P. Foreign bodies and caustic lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:679-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ciriza C, García L, Suárez P, Jiménez C, Romero MJ, Urquiza O, Dajil S. What predictive parameters best indicate the need for emergent gastrointestinal endoscopy after foreign body ingestion? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wu WT, Chiu CT, Kuo CJ, Lin CJ, Chu YY, Tsou YK, Su MY. Endoscopic management of suspected esophageal foreign body in adults. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li ZS, Sun ZX, Zou DW, Xu GM, Wu RP, Liao Z. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper-GI tract: experience with 1088 cases in China. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:485-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tokiwa T, Kobayashi Y, Ike K, Morishima Y, Sugiyama H. Detection of Anisakid Larvae in Marinated Mackerel Sushi in Tokyo, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2018;71:88-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Furuya K, Nakajima H, Sasaki Y, Urita Y. Anisakiasis: The risks of seafood consumption. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018;21:1492-1494. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Conigliaro R, Bedogni G. A simple latex protector hood for safe endoscopic removal of sharp-pointed gastroesophageal foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:458-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang S, Wang J, Wang J, Zhong B, Chen M, Cui Y. Transparent cap-assisted endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper esophagus: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1339-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Extraction of entrapped capsules from the small bowel by means of push-and-pull enteroscopy with the double-balloon technique. Endoscopy. 2005;37:591-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Miehlke S, Tausche AK, Brückner S, Aust D, Morgner A, Madisch A. Retrieval of two retained endoscopy capsules with retrograde double-balloon enteroscopy in a patient with a history of complicated small-bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhang S, Cui Y, Gong X, Gu F, Chen M, Zhong B. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in South China: a retrospective study of 561 cases. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1305-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |