Published online May 16, 2019. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v11.i5.383

Peer-review started: January 29, 2019

First decision: April 13, 2019

Revised: May 9, 2019

Accepted: May 13, 2019

Article in press: May 14, 2019

Published online: May 16, 2019

Processing time: 107 Days and 15 Hours

Capecitabine is considered a first line agent in adjuvant therapy for breast and colorectal cancer. However, cases of severe diarrhea have been reported with increasing frequency in recent years. When diarrhea is severe and prolonged, capecitabine associated ileitis should be considered as a possible etiology.

Herein, we present two cases of capecitabine ileitis, specifically involving the terminal ileum and ascending colon. We will demonstrate the disease course and treatment modalities applied to alleviate this condition, as well as discuss the merits of using colonoscopy to aid in diagnosis.

Ultimately our cases demonstrate that symptomatic management with traditional anti-diarrheal medications is largely ineffective. Prompt recognition and discontinuation of capecitabine is an imperative step in proper management of this condition and colonoscopy with biopsy can be helpful when the diagnosis is unclear.

Core tip: There have been nine published cases describing capecitabine associated ileitis, and only four of these cases document use of colonoscopy. We are presenting the fifth and sixth case reports of colonoscopy-assisted diagnosis of this condition. Combining analysis of these six colonoscopy reports, we determined patterns in the presentation of this condition. Given that the differential etiologies of diarrhea are so broad, we believe that our findings collectively can improve the diagnostic accuracy and optimize treatment. Additionally, we believe that colonoscopy with biopsy should be indicated as a standardized diagnostic measure in patients on capecitabine with refractory diarrhea.

- Citation: Dao AE, Hsu A, Nakshabandi A, Mandaliya R, Nadella S, Sivaraman A, Mattar M, Charabaty A. Role of colonoscopy in diagnosis of capecitabine associated ileitis: Two case reports. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 11(5): 383-388

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v11/i5/383.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v11.i5.383

Capecitabine (Xeloda) is an oral 5-fluorouracil (FU) prodrug used as adjuvant and/or palliative chemotherapy in the treatment of colorectal and breast cancer. According to monotherapy trials, up to 53% of patients develop diarrhea as an adverse effect. This diarrhea is usually self-limited, allowing patients to continue capecitabine with dose limitation[1]; however, in rare cases capecitabine associated ileitis can occur, causing a severe persistent diarrhea characterized on endoscopy by mucosal inflammation in the ileum despite discontinuation of the drug. This complication has the potential to result in severe pain, electrolyte imbalances, nutritional deficiencies, and life-threatening hemodynamic instability. Our two cases characterize the disease course of capecitabine associated ileitis with a focus on imaging, colonoscopy findings, and treatment options for this uncommon condition.

(1) Case 1: A 72-year-old Caucasian female presented to the hospital with severe watery diarrhea; and (2) Case 2: A 42-year-old African American female presented to the hospital with severe voluminous bloody diarrhea.

(1) Case 1: She denied bloody stools, abdominal pain, fevers, or chills; and (2) Case 2: She was having six to ten bowel movements per day (some of which were bloody) with associated abdominal pain and fever.

(1) Case 1: The patient had a past medical history of with stage IIIC ascending colon adenocarcinoma and previously underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy and was started on adjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine. She additionally had a history significant for diabetes, hypertension, ischemic cardiomyopathy with a biventricular pacemaker, as well as coronary artery disease status post stent placement; and (2) Case 2: The patient had a past medical history of stage IIIC recurrent right breast cancer as well as deep vein thrombosis with pulmonary embolus on lovenox.

(1) Case 1: The patient was a nonsmoker and social drinker, with no relevant family history; and (2) Case 2: The patient was a nonsmoker and denied alcohol use. Family history was negative for cancer and otherwise noncontributory.

(1) Case 1: On admission, physical examination was notable for multiple oral ulcers, however she had a nontender abdominal exam and was otherwise unremarkable; and (2) Case 2: Physical exam was notable for mild tenderness to palpation of the epigastrium and right lower quadrant of the abdomen. Initial labs were notable for hypokalemia (K 2.9) and mild anemia (Hb 10.2), however there was no leukocytosis (WBC 4.4) or kidney injury (Cr 0.8).

(1) Case 1: Initial labs were concerning for severe malnutrition (albumin 1.7), leukopenia (WBC 1.5 K/mm3 with ANC 900) and acute kidney injury (Cr 1.32, baseline 1). Laboratory examination also included infectious workup with Clostridium difficile, stool cultures, ova and parasites, and rotavirus, all of which resulted as negative. Given her cardiac risk factors, there was concern for ischemic colitis, however lactate was normal and she denied any history of abdominal pain, melena, or hematochezia; and (2) Case 2: Laboratory examination included negative infectious workup with Clostridium difficile, Giardia, Ova and Parasites, stool culture, and rotavirus all resulting as negative.

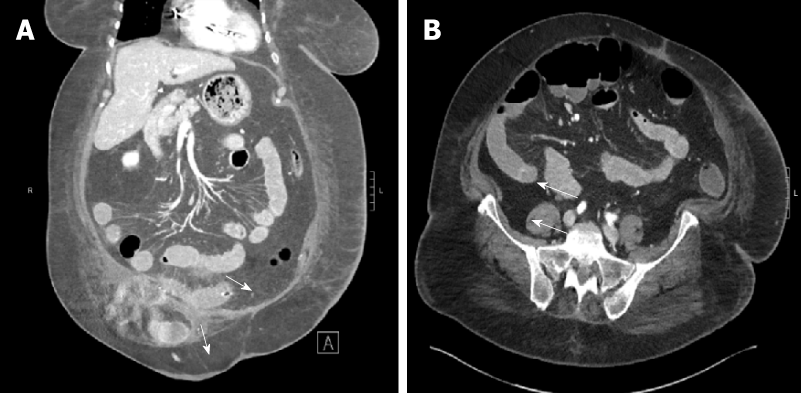

(1) Case 1: Initial computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis showed mildly dilated fluid-filled loops of small bowel with adjacent engorgement of vasa recta and mesenteric edema consistent with enteritis (Figure 1); and (2) Case 2: Initial CT Abdomen and Pelvis with contrast revealed marked thickening of the small bowel with fluid filled bowel loops.

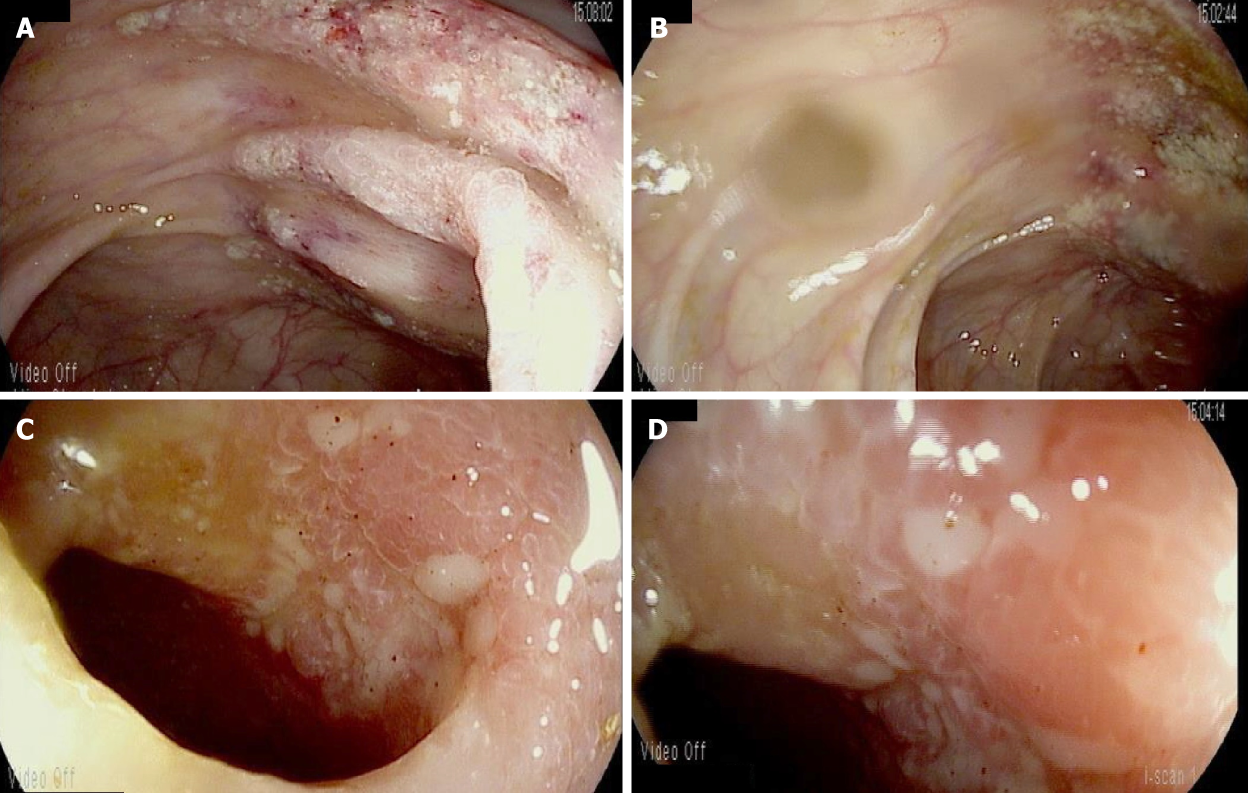

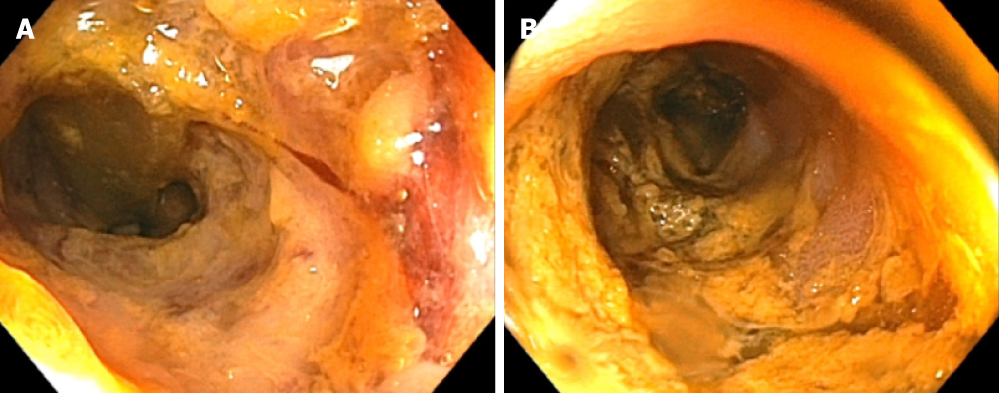

(1) Case 1: This prompted subsequent colonoscopy and ileoscopy, which demonstrated granular erythematous mucosa with ulceration both above and below the ileocolonic anastomosis (Figure 2). Ileal biopsy showed mucosal erosion with acute inflammation and occasional atypical glands most likely representing reactive changes without evidence of Cytomegalovirus or herpes simplex viruses on immunohistochemical stains; and (2) Case 2: On colonoscopy, the terminal ileum was found to have diffuse pseudomembranes with severe inflammatory exudates and spontaneous bleeding (Figure 3). The right colon demonstrated erythema and mucosal thickening suggestive of mild colitis. Biopsy from the ileum and colon showed necrotic and inflammatory debris, but was negative for granulomas or viral inclusions.

(1) Case 1: The final diagnosis was refractory diarrhea due to capecitabine associated ileitis; and (2) Case 2: The final diagnosis was bloody diarrhea due to capecitabine associated ileitis.

On admission, the patient’s capecitabine was held. In addition to fluid and electrolyte resuscitation, diarrhea was addressed with loperamide, lomotil, and octreotide - however symptoms did not improve. Cholestyramine (4 mg daily) was trialed to counter any biliary diarrhea that may have contributed due to her prior right hemicolectomy. Additionally oral budesonide was trialed for three days in case of chemotherapy induced mucositis given the development of oral sores. She eventually required a three week course of total parenteral nutrition to address her severe protein deficiency.

Capecitabine was held on admission due to concern that this was a potential etiology of the diarrhea. She underwent a short course of antibiotics that was then discontinued when infectious etiology was adequately ruled out. Despite stopping chemotherapy, diarrhea persisted and workup with a colonoscopy including ileoscopy was performed. As in the case above, the patient was initially fluid and electrolyte resuscitated and once infection was no longer a concern she was trialed on various anti-diarrheal medications that were ultimately unsuccessful including lomotil, loperamide, cholestyramine, and octreotide. Additionally, she was trialed on oral budesonide which improved abdominal pain however did not resolve the diarrhea. There was a discussion regarding initiation of parenteral nutrition however it was ultimately decided against as symptoms appeared to be improving by this time. Instead, she was trialed on a low lactose, low fat, high protein diet which seemed to contribute to the improvement of diarrheal symptoms by the end of her course.

(1) Case 1: Despite these interventions, the patient still had voluminous diarrhea for a total of four weeks after cessation of capecitabine. To date, she has not been restarted on capecitabine at any dose given the severity of her symptoms; and (2) Case 2: By four weeks after discontinuation of capecitabine, diarrhea had resolved and stools were improving in frequency and consistency. As in case 1, this patient was never restarted on capecitabine due to the severity of her diarrhea.

Capecitabine is an oral precursor of the antineoplastic agent FU. FU is a pyrimidine analog that inhibits the synthesis of the nucleoside thymidine, therefore interfering with normal DNA replication. Administration of FU is intravenous and nonspecific, resulting in harsh widespread toxicities including neutropenia, stomatitis, and diarrhea[2]. Capecitabine was developed as a preferred agent to FU due to its oral route of administration and its multi-step metabolism conferring a more targeted distribution of active metabolite. It is considered a first line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer when single agent fluoropyrimidines are indicated. The most clinically significant adverse effects of capecitabine include hand-foot syndrome and diarrhea, both of which can be so severe that treatment must be redirected.

Capecitabine induced ileitis is a rare yet severe adverse effect that has only been documented in few cases in the recent past. Roche Drug Safety identifies the incidence of suspected ileitis to be less than 0.01% of their patient population[3]. It was first recognized as a complication of capecitabine in 2012 by Radwan et al[3], however its exact pathophysiology is still unknown. It has been proposed that decreased blood flow to intestinal mucosa and pro-inflammatory cytokines may contribute to mucosal injury[4]. In a report by Lee et al[5], the authors describe two cases of capecitabine induced ileitis based on radiological evidence. Key management principles include early recognition of the adverse reaction, immediate cessation of capecitabine, and supportive therapy with total parenteral nutrition. In one of these cases, the diarrhea subsided 29 d post cessation of capecitabine[5]. This was the same amount of time required to resolve the diarrhea after stopping the chemotherapy as reported in our two cases. These findings suggest that capecitabine induced ileitis can last multiple weeks and is not likely to respond to more conservative methods such as antimotility agents (i.e., lomotil, loperamide) or antisecretory agents (i.e., octreotide).

To date, there have been only nine published cases describing capecitabine associated ileitis, and only four of these cases document use of colonoscopy in diagnosis[6-9]. We are presenting the fifth and sixth case reports of colonoscopy-assisted diagnosis of this condition. Combining our analysis of these six colonoscopy reports (Table 1), we have determined some patterns in the presentation of this condition. Firstly, capecitabine associated ileitis tends to localize in the terminal ileum. Secondly, a granular erythematous appearance of mucosa with ulcerations is commonly seen. Two of the six reports disclose a biopsy that is positive for eosinophilic infiltrates, and one report from our institution describes a pseu-domembrane with inflammatory exudates. Given that the differential etiologies of diarrhea in a hospitalized patient is so broad (colitis, bacterial vs viral infection, inflammation, medication-induced) we believe that these findings collectively can improve the diagnostic accuracy of this condition and optimize treatment options. Additionally, we believe that colonoscopy with biopsy should be indicated as a standardized diagnostic measure in patients on capecitabine with diarrhea refractory to conservative methods.

| Case report | Findings seen on (1) colonoscopy and (2) histology |

| Barton[6], 2006 | (1) Ulcerative ileitis (2) Eosinophilic infiltrates |

| Al-Gahmi et al[7], 2012 | (1) Isolated ulceration in the terminal ileum (2) Inflammatory changes and eosinophilic infiltrate but no evidence of malignancy or granulomas |

| Mokrim et al[8], 2014 | (1) Inflammatory changes in the ileal mucosa (2) Absence of intraepithelial lymphocytic infiltrates in favour of a non-atrophic ileitis |

| Van Hellemond et al[9], 2018 | Terminal ileitis Extensive inflammation of the small intestine |

| Case 1 | (1) Evidence of granular erythematous mucosa with ulceration both above and below the ileocolonic anastomosis in the terminal ileum and ascending colon(2) Mucosal erosion with acute and chronic inflammation and occasional atypical glands most likely representing reactive changes without evidence of Cytomegalovirus or herpes simplex viruses on immunohistochemical stains |

| Case 2 | (1) On colonoscopy, the terminal ileum was found to have diffuse pseudomembranes with severe inflammatory exudates and spontaneous bleeding.(2) Necrotic and inflammatory debris, but was negative for granulomas or viral inclusions. |

In all published cases, approach to management posed a significant challenge. It appears that a combination or trial of cessation of capecitabine, fluid and nutritional resuscitation with TPN, and administration of steroids have shown some benefit[6,7,10].

Ultimately our cases demonstrate that symptomatic management with traditional anti-diarrheal medications is largely ineffective. There may be some role in symptomatic management of abdominal pain with the use of oral steroids, however this prospect requires further study. Overall, capecitabine induced ileitis is a serious adverse effect that is being recognized with increasing frequency in recent years. Supportive management with parenteral nutrition, hydration, and pain management are the cornerstone of treatment while inflamed intestinal mucosa heals. Prompt recognition and discontinuation of capecitabine is an imperative step in proper management of this condition and colonoscopy with biopsy can be helpful when the diagnosis is unclear.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Guo JT, Lee CL, Smith RC, Wan QQ S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Saif MW, Katirtzoglou NA, Syrigos KN. Capecitabine: an overview of the side effects and their management. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:447-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Walko CM, Lindley C. Capecitabine: a review. Clin Ther. 2005;27:23-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Radwan R, Namelo WC, Robinson M, Brewster AE, Williams GL. Ileitis secondary to oral capecitabine treatment? Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:154981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Soares PM, Mota JM, Souza EP, Justino PF, Franco AX, Cunha FQ, Ribeiro RA, Souza MH. Inflammatory intestinal damage induced by 5-fluorouracil requires IL-4. Cytokine. 2013;61:46-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee SF, Chiang CL, Lee AS, Wong FC, Tung SY. Severe ileitis associated with capecitabine: Two case reports and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:1398-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Barton D. Ulcerative ileitis secondary to adjuvant capecitabine for colon cancer: a case report. UICC World Cancer Congress, Washington, DC, July 2006, 84-41. . |

| 7. | Al-Gahmi AM, Kerr IG, Zekri JM, Zagnoon AA. Capecitabine-induced terminal ileitis. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mokrim M, Aftimos PG, Errihani H, Piccart-Gebhart M. Breast cancer, DPYD mutations and capecitabine-related ileitis: description of two cases and a review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:pii: bcr2014203647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | van Hellemond IEG, Thijs AM, Creemers GJ. Capecitabine-Associated Terminal Ileitis. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11:654-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bouma G, Imholz AL. [Ileitis following capecitabine use]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2011;155:A3064. [PubMed] |