Published online Feb 16, 2019. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v11.i2.115

Peer-review started: August 17, 2018

First decision: August 31, 2018

Revised: January 29, 2019

Accepted: February 13, 2019

Article in press: February 13, 2019

Published online: February 16, 2019

Processing time: 185 Days and 9.9 Hours

Stevens - Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a severe adverse drug reaction associated with involvement of skin and mucosal membranes, and carries significant risk of mortality and morbidity. Mucus membrane lesions usually involve the oral cavity, lips, bulbar conjunctiva and the anogenitalia. The oral/anal mucosa and liver are commonly involved in SJS or TEN. However, intestinal involvement is distinctly rare. We herein review the current literature regarding the gastrointestinal involvement in SJS or TEN. This review focuses mainly on the small bowel and colonic involvement in patients with SJS or TEN.

Core tip: The oral/anal mucosa and liver are commonly involved in Stevens -Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). However, intestinal involvement is distinctly rare. We herein review the current literature regarding the gastrointestinal (GI) involvement in SJS or TEN. The extent of the GI involvement, clinical presentations, endoscopic and histopathological features, treatment options, and prognosis are described in this article.

- Citation: Jha AK, Suchismita A, Jha RK, Raj VK. Spectrum of gastrointestinal involvement in Stevens - Johnson syndrome. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 11(2): 115-123

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v11/i2/115.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v11.i2.115

Stevens - Johnson syndrome (SJS) comprises a widespread, cutaneous eruption with features resembling erythema multiforme in combination with constitutional symptoms such as fever and malaise, and mucosal lesions classically affecting the eyes, mouth, and genitalia[1]. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is defined by involvement of at least 30% of total body surface area (TBSA) of the skin, and frequently involves at least two mucus membranes[2]. The skin involvement in SJS and SJS/ TENS overlap is < 10% and 10%-30% of TBSA, respectively. Fuchs syndrome or atypical SJS a very rare entity is defined as SJS-like mucositis without skin involvement[3].

Extracutaneous manifestations of the SJS or TEN can occur and may involve the conjunctiva, buccal mucosa, trachea, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and genitourinary tract. Mucus membrane lesions usually involve the oral cavity, lips, bulbar conjunctiva and the anogenitalia. The mucosal lesions may go parallel, may follow or even precede the rash[4,5]. We herein review the current literature regarding the GI involvement in SJS or TEN. This review focuses mainly on the small bowel and colonic involvement in patients with SJS or TEN, which are distinctly rare.

SJS or TEN have been postulated to be a hypersensitivity reaction triggered by a variety of stimuli[4,6]. The most common precipitants are drugs followed by infections with mycoplasma, herpes and cytomegalo virus[7]. Beta lactam/sulfonamide antibiotics, NSAIDs (diclofenac, ketorolac, sulindac, piroxicam, and oxyphenbutazone), chlormezanone, and aromatic anticonvulsant are the most common drugs responsible for SJS or TEN.

The pathogenesis of SJS or TEN appears to be an immune mediated process. Damage of keratinocytes and mucosal epithelium is mediated by a cell-mediated and cytotoxic immune process. Activated T-cells stimulate extensive apoptosis by direct cell-cell interactions (via CD95 and Fas ligand-mediated signaling pathway), and by secretion of factors such as perforin, granulysin and cytokines (TNFa)[8-10]. The skin and other tissues appears to be affected by common mechanism of the Fas-ligand and the perforin-granulysin pathways. The mechanism by which SJS or TEN affects the intestine is identical to one that causes skin lesions. The pathologic features of both the skin and GI lesions are similar to acute graft-vs-host disease such as full-thickness epithelial necrosis and detachment, epithelial crypt cells necrosis, and a relative sparing of lamina propria. However, lymphomononuclear cell infiltrations of lamina propria can be present in some patients[11,12]. The colonic mucosa is found to constitutively express CD95[13]. The mechanism of delayed and/or persistent intestinal inflammation is not clear.

GI complications are not uncommon in SJS or TEN and are usually mild. Some of the GI manifestations can be observed in about 10% of patients with SJS or TEN[4,14]. Severe GI involvement of SJS or TEN is rare but potentially life-threatening. In a study by Yamane et al[14], GI involvement noted in 9 (10%) of patients with SJS or TEN (n = 87). Common GI symptoms were diarrhea, intestinal bleeding, and severe appetite loss. One patient was expired due to perforation of intestine, DIC and pneumonia[14]. The oral/anal mucosa and liver are frequently involved in patients with SJS or TEN[14,15]. Esophageal involvement in patients with SJS or TEN is not so rare. Esophageal ulcer and chronic esophageal stricture formation have been described in SJS or TEN[16-20]. Small bowel and colonic involvement are distinctly rare. We were able to find detailed reports of about 25 cases [age (range) 8-81 years; male: female ratio of 7:18] of SJS or TEN with GI involvement (Table 1 and Table 2)[11,12,21-39]. Details of patients with small bowel and colonic involvement are summarized in Table 2. Small bowel and colonic lesions are often associated with lesions in the other parts of GI tract. Isolated involvement of the small bowel and colon does occur but is quite uncommon. The “skip” involvement of the GI tract has been described in SJS or TEN with the distal stomach and small and/or large bowel involvement, and sparing of the esophagus and proximal stomach[37].

| Ref. | Age (yr), Sex | TBSA (%) | GI Symptoms | Extent of GI involvement/Complications | Treatment | Outcome |

| [21] | 71, F | 30 | GI bleed, D | (1) Ileus, Intraabdominal abscess, Jejunal perforation, Gastiric/colonic ulcer; (2) LA grade C esophagitis | (1) Steroid, IVIg; (2) Plasmapheresis; (3) Surgery | Survived (LOS-2 mo) |

| [14] | 74, M | 40 | - | Intestinal perforation | Steroid, IVIg | Expired (after 31 d) |

| [22] | 44, F | 0 | GI bleed | Gastric/rectal erosions | Steroid | Survived (LOS-31 d) |

| [23] | 62, F | > 30 | AP, V | Intestinal infarction | Intestinal resection | Expired (after few days) |

| [24] | 28, M | 90 | AD | Mesentric ischaemia | (1) IVIg; (2) Jejeunal-ileal resection | Survived (LOS-10 d) |

| [25] | 56, F | 60 | D, Hypoalbumenia | Esophageal/duodenal/ileocolonic erosions | Steroid, IVIg, TPN | Survived |

| [26] | 61, F | - | Odynophagia, GI bleed | Esophageal/recto-sigmoid ulcers | Steroid | Survived (LOS-1 mo) |

| [27] | 23, M | - | AP,D, GI bleed | Colonic ulcers | Steroid, Probiotics | Survived (DOI-2 mo) |

| [28] | 8, M | 40 | V, AD, D | Ileoileal intussusception | Surgery | Survived (LOS-15 d) |

| [29] | 71, F | 95 | AD, D, GI bleed | Esophageal/gastric/sigmoid colonic erosions | IVIg | Expired (after 24 h) |

| [30] | 30, F | 61 | D, GI bleed | Jejunal/colonic ulcers | Steroid, TPN, PE | Survived (DOI-5 mo) |

| [31] | 52, F | > 30 | D, GI bleed | Ileocolonic stenosis | Ileo-cecal resection | Survived |

| [32] | 17, M | 73 | D, GI bleed | (1) Microscopic duodenitis; (2) Ileocolonic ulcerations | Steroid, TPN, EN, Probiotics | Survived (DOI-6 mo) |

| [33] | 62, M | 70 | Massive GI bleed | Confluent esophago-gastroduodenal ulceration | Steroids | Expired (after 21 d) |

| [34] | 81, F | 40 | Jaundice | Mucosal erosions in upper GI tract | IVIg | Survived (LOS-14 d) |

| [35] | 46, F | > 75 | D, GI bleed | Mucosal sloughs/ulcers (autopsy) | Steroids, Cyclophosphamide | Expired (LOS-9 mo) |

| [36] | 48, F | 40 | D, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy | (1) Gastritis; (2) Multiple ileal strictures; (3) Multiple pseudodiverticular sacs; (4) Pseudomembranes formation | TPN, Ileal resection | Survived (LOS > 9 mo) |

| [12] | 69, F | 37 | AP, GI bleed | (1) Sigmoid colon ulcers; (2) Perforations (sigmoid colon, cecum); (3) Ileal necrosis | Steroids, Ileal resection/ colectomy | Survived (LOS-5 mo) |

| [11] | 4 cases (mean 42 (3F:1M) | Mean 37 | AP and GI bleed in all | (1) Duodenitis (2 cases); (2) Oesophagitis (1 case); (3) Procosigmoiditis (4 cases); (4) Jejunoileal involvement (1 case) | Ileal resection (1case) | Expired (3 cases), Survived (1 case) |

| [37] | 41, F | > 70 | AP, D, GI bleed | (1) Gastroduodenitis; (2) Sigmoiditis | Steroid | Expired (after 15 d) |

| [38] | 53, F | > 75 | AP, D | Small bowel ulcers | Steroid | Expired (after 17 d) |

| [39] | 48, F | - | AP, D, GI bleed | Subacute intestinal obstruction | Steroid | Expired (after 8 hrs) |

| Total reported cases | 25 |

| Age (range) | 8-81 yr |

| M:F (ratio) | 7:18 |

| TBSA (%) | 0%-95% (all patients except one had > 30% of skin involvement) |

| Time of appearance of GI symptoms | 0 wk-7 wk (usually within two weeks) after appearance of rash/mucosal lesions |

| Chief symptoms | GI bleeding-17 (68%) Diarrhoea-13 (52%) Abdominal pain-10 (40%) Abdominal distension-3 (12%) Vomiting-2 (8%) |

| Complications/ Extent of GI involvement | Luminal erosions/inflammation-15 (60%) Ulcer (Single or multiple)-9 (36%) [Large bowel (6). Small bowel (3), Esophageal (3), Gastric (2)] Perforation-3 (12%) (small bowel/colon) Strictures-2 (8%) (ileal/ileo-colonic) Mesentric ischaemia/ Intestinal infarction/ Ileoileal intussusceptions,/ Pseudodiverticular sacs/ Intraabdominal abscess,/ Pseudomembranes formation/ Subacute intestinal obstruction-One each Malabsorption/ Hypoalbumenia/ Protein-losing enteropathy- One each |

| Treatment | Medical [Steroids (14), IVig (4), TPN (4), Probiotics (2), PP (1), PE (1), EN (1)] Surgery-8 (32%) |

| Outcome | Survived- 14 (56%) [LOS (range)- 10 d -9 mo, DOI (range)-1-6 mo] Expired-11 (44%) |

GI manifestations usually reveals within two weeks of cutaneous lesions, but it can present many weeks after initial cutaneous symptoms. Symptoms may persist for months after disappearance of skin lesions, and duration of as long as 9 mo have been described (Table 1 and Table 2). Passage of a tubular mass of necrotic epithelium and fibrinous exudates in the stool was reported after 25 d of skin lesion[35].

The usual presenting symptoms include GI bleeding (hemetemesis, melena, and hematochezia), diarrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distension and dysphagia. Diarrhoea is usually profuse and watery. Patients may also present with blood mixed in with the stool. Inflammation of GI tract such as esophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis, jejunitis, ileitis and colitis are common GI lesions (60%). Ulcers in the colon, small bowel, esophagus and stomach are responsible for GI bleeding in these patients (36%). Patients can be diagnosed with ulcers in multiple locations. Large bowel is most common site of ulcer followed by small bowel and stomach. Intestinal perforation and strictures (single or multiple) have been reported in three (12%) and two (8%) patients, respectively. Mesentric ischaemia, intestinal infarction, intraabdominal abscess, ileoileal intussusceptions, and subacute intestinal obstruction (one patient each) have also been described in SJS. Patients can also presents with protein-losing enteropathy, malabsorption syndromes, and hypoalbumenia. Evaluation of a patient presented with diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy and malabsorption syndrome revealed multiple ileal strictures, pseudodiverticular sacs and pseudomembranes formation. Stricture, intestinal wall edema, intussusception and luminal stenosis caused by erosion and sublation of intestinal mucosa are the reasons for intestinal obstruction in these patients[31,36,39]. Laprotomy and necropsy of a patient presented with subacute intestinal obstruction showed hemorrhage, petechie, ecchymosis, and congestion in the stomach, small bowel, proximal large bowel and gall bladder[39]. Heye et al[40] showed an association between perforation of sigmoid diverticulitis and SJS, though the casual relationship was unclear.

SJS or TEN is mostly treated with prolonged antibiotic course and immunosuppressive drugs and the GI symptoms may appear late in the course of illness. The differential diagnosis in such clinical scenario often includes infective colitis especially viral, antibiotic associated diarrhea, pseudomembranous colitis and first episode of inflammatory bowel disease.

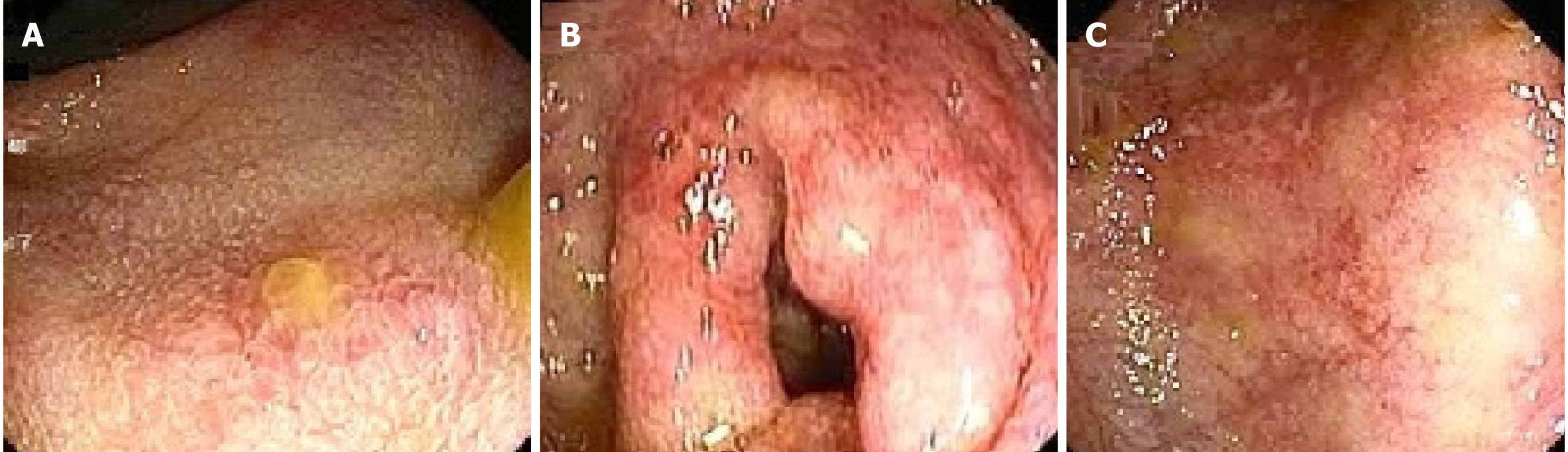

There are various endoscopic findings observed in patients with SJS/TEN. These include the hyperemia, erythema, congestion, friability, erosions, superficial or deep ulcerations and necrotic plaque formation with mucosal sloughing (Figure 1) (Table 1). Ulcer may be irregular, friable and covered with white fibrin-like exudates[21]. Whitish plaques and pseudomembrane formation over the damaged mucosa are the other endoscopic findings in SJS or TEN. Although colonic pseudomembrane has not been reported yet, ulcerations with adherent pseudomembrane have been described in the esophagus and ileum[16,36].

Histopathological (HPE) features of biopsy or autopsy specimen include mucosal ulceration with epithelial necrosis and lymphomononuclear cell infiltrations in early stage, and severe necrotic ulcerations, lymphomononuclear infiltration of the lamina propria and inflamed granulation tissue, later in the course[11,12,37]. Lamina propria is relatively spared in these patients. HPE of healing colonic ulcer showed marked crypt architectural distortion and significant crypt loss, suggesting injury to the crypt stem cell population[21].

Hepatic complications of SJS or TEN includes asymptomatic hepatic enzymes elevation, hepatitis, cholestastic hepatitis, and hepatic failure. In a study by Yamane et al[14], hepatitis was the most common complication in seen in 47% of patients with SJS or TEN. Cholestatic liver disease, which may precede the skin manifestations of SJS or TEN, has been reported in nearly 12 cases of SJS or TEN[41-45]. Acute liver failure also has been described in association with SJS or TEN; however the exact casual relationship was not established[46].

Pancreas involvement is rarely described in patients with SJS or TEN. A few cases of asymptomatic pancreatic enzymes elevation and acute pancreatitis are described in SJS or TEN[47-49]. In a study by Dylewski et al[47], enteral nutrition was tolerated by all patients of TEN with asymptomatic pancreatic enzymes elevation. Therefore, in the absence of symptomatic pancreatitis, patients with SJS or TEN can be supported with enteral nutrition[47].

Treatment of SJS or TEN is still controversial. Withdrawal of offending drugs and admission in a burn intensive care unit is recommended. Disease severity and prognosis can be assessed with the SCORTEN criteria[50].The treatment of SJS or TEN is largely supportive. Supportive care include the management of airway, fluid and electrolyte balance, monitoring of renal function, nutritional supplementation, adequate analgesia, care of skin and mucosal surfaces, and prevention of infection. Currently used medical therapy comprised of systemic corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg), cyclosporine, plasmapheresis, plasma exchange, antitumor necrosis factor drugs and N-acetylcysteine, but none has been established as the most effective therapy. Systemic steroids are used as standard of care for treatment of SJS or TEN. A few case series have reported favorable outcomes in patients treated with corticosteroids and immunoglobulin[8,51,52]. But, data does not support use of steroid as sole therapy, and are no longer recommended[53]. A meta-analysis showed no survival benefit among SJS or TEN patients treated with intravenous immunoglobulin[54].

Patients of SJS or TEN with GI involvement may be treated conservatively or may require surgery. Conservative treatment consists of supportive measures, systemic steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, probiotics, plasma exchange, and supplemental nutrition. Role of steroid in patients with SJS or TEN with GI involvement is trickier. Steroids may exacerbate mucosal sloughing, GI bleeding and perforation in SJS or TEN. Huang et al[54] showed decreased rates of GI complications of SJS or TEN after steroids were removed from their treatment protocol. Therefore, the choice of treatment depends on the available guidelines and the experience of the treating physician. A multidisciplinary approach is warranted, and treatment should be determined on an individual basis. Out of 25 patients, surgery was performed in eight (32%) cases. It is worth mentioning that in the patients who required a surgical intervention (8 patients) for GI manifestations, all but one patient was survived (Table 1).

Patients with SJS or TEN and intestinal involvement have a poor prognosis. Nearly half (44%) of reported cases had fatal outcome (Table 2). Patients who survived have increased risk of late GI complications. These include strictures of the esophagus, ileum and anal canal as well as ileal pseudodiverticulae[15,17,36].

GI complications are not uncommon in SJS or TEN and are usually mild. Severe GI involvement of SJS or TEN is rare but potentially life-threatening. GI manifestations usually reveal within two weeks of cutaneous lesions, but these symptoms may be delayed. These patients may be treated conservatively or may require surgery. The conservative treatment is mainly supportive and current data does not support use of steroid or IVIg. A multidisciplinary approach is warranted and treatment should be determined on an individual basis.

Pathogenesis of SJS or TEN is still not clear. Mechanism of patchy/skip involvement of GI tract are unknown. Better understanding of pathogenesis may help to develop a new and effective therapy for this dangerous disease. Because of rarity of disease, the randomized controlled trials regarding the efficacy of various drugs are difficult to perform. Therefore, multicentre randomized controlled trials are warranted to compare the efficacy of available treatment options.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Hashimoto R, Huguet JM, Fouad YM S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD. Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2003; 870-871. |

| 2. | Chan HL. Observations on drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in Singapore. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:973-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li K, Haber RM. Stevens-Johnson syndrome without skin lesions (Fuchs syndrome): a literature review of adult cases with Mycoplasma cause. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:963-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, Spence RJ, Peck MD, Jeng JC, Mozingo DW, Yowler CJ, Sheridan RL, Ahrenholz DH, Caruso DM, Foster KN, Kagan RJ, Voigt DW, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, Wolf S, Molitor F. A multicenter review of toxic epidermal necrolysis treated in U.S. burn centers at the end of the twentieth century. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23:87-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roujeau JC. The spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a clinical classification. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:28S-30S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sontheimer RD, Garibaldi RA, Krueger GG. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Auquier-Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, Naldi L, Correia O, Schröder W, Roujeau JC; SCAR Study Group. Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions. Correlations between clinical patterns and causes of erythema multiforme majus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: results of an international prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1019-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Viard I, Wehrli P, Bullani R, Schneider P, Holler N, Salomon D, Hunziker T, Saurat JH, Tschopp J, French LE. Inhibition of toxic epidermal necrolysis by blockade of CD95 with human intravenous immunoglobulin. Science. 1998;282:490-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in RCA: 722] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abe R, Yoshioka N, Murata J, Fujita Y, Shimizu H. Granulysin as a marker for early diagnosis of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:514-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chung WH, Hung SI, Yang JY, Su SC, Huang SP, Wei CY, Chin SW, Chiou CC, Chu SC, Ho HC, Yang CH, Lu CF, Wu JY, Liao YD, Chen YT. Granulysin is a key mediator for disseminated keratinocyte death in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Nat Med. 2008;14:1343-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in RCA: 544] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chosidow O, Delchier JC, Chaumette MT, Wechsler J, Wolkenstein P, Bourgault I, Roujeau JC, Revuz J. Intestinal involvement in drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis. Lancet. 1991;337:928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Carter FM, Mitchell CK. Toxic epidermal necrolysis--an unusual cause of colonic perforation. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:773-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Möller P, Koretz K, Leithäuser F, Brüderlein S, Henne C, Quentmeier A, Krammer PH. Expression of APO-1 (CD95), a member of the NGF/TNF receptor superfamily, in normal and neoplastic colon epithelium. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yamane Y, Matsukura S, Watanabe Y, Yamaguchi Y, Nakamura K, Kambara T, Ikezawa Z, Aihara M. Retrospective analysis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in 87 Japanese patients--Treatment and outcome. Allergol Int. 2016;65:74-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ting HC, Adam BA. Stevens-Johnson syndrome. A review of 34 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:587-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lamireau T, Leauté-Labrèze C, Le Bail B, Taieb A. Esophageal involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Endoscopy. 2001;33:550-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V. Esophageal stricture as a late sequel of Stevens-Johnson syndrome in adults: incidental detection because of foreign body impaction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:437-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Carucci LR, Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diffuse esophageal stricture caused by erythema multiforme major. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:749-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Edell DS, Davidson JJ, Muelenaer AA, Majure M. Unusual manifestation of Stevens-Johnson syndrome involving the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract. Pediatrics. 1992;89:429-432. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Heer M, Altorfer J, Burger HR, Wälti M. Bullous esophageal lesions due to cotrimoxazole: an immune-mediated process? Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1954-1957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brown CS, Defazio JR, An G, O'Connor A, Whitcomb E, Hart J, Gottlieb LJ. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis with Gastrointestinal Involvement: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38:e450-e455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Majima Y, Ikeda Y, Yagi H, Enokida K, Miura T, Tokura Y. Colonic involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome-like mucositis without skin lesions. Allergol Int. 2015;64:106-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fava P, Astrua C, Cavaliere G, Brizio M, Savoia P, Quaglino P, Fierro MT. Intestinal involvement in toxic epidermal necrolysis. A case report and review of literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1843-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pradka SP, Smith JR, Garrett MT, Fidler PE. Mesenteric ischemia secondary to toxic epidermal necrolysis: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2014;35:e346-e352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nishimura K, Abe R, Yamaguchi M, Ito T, Nakazato S, Hamade Y, Saito N, Moriuchi R, Katsurada T, Watanabe M, Iitani MM, Shimizu H. A case of toxic epidermal necrolysis with extensive intestinal involvement. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:P14. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fortinsky KJ, Fournier MR, Saloojee N. Gastrointestinal involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome: prompt recognition and successful treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:285-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jha AK, Goenka MK. Colonic involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a rare entity. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bouziri A, Khaldi A, Hamdi A, Borgi A, Ghorbel S, Kharfi M, Hadj SB, Menif K, Ben Jaballah N. Toxic epidermal necrolysis complicated by small bowel intussusception: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:e9-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kedward AL, McKenna K. A fatal case of toxic epidermal necrolysis with extensive intestinal involvement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sakai N, Yoshizawa Y, Amano A, Higashi N, Aoki M, Seo T, Suzuki K, Tanaka S, Tsukui T, Sakamoto C, Arai M, Yamamoto Y, Kawana S. Toxic epidermal necrolysis complicated by multiple intestinal ulcers. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:180-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Otomi M, Yano M, Aoki H, Takahashi K, Omoya T, Suzuki Y, Nakamoto J, Kataoka K, Yagi Y, Yamamoto Y. [A case of toxic epidermal necrolysis with severe intestinal manifestation]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;105:1353-1361. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Powell N, Munro JM, Rowbotham D. Colonic involvement in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Garza A, Waldman AJ, Mamel J. A case of toxic epidermal necrolysis with involvement of the GI tract after systemic contrast agent application at cardiac catheterization. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:638-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Huang DB, Wu JJ, Lahart CJ. Toxic epidermal necrolysis as a complication of treatment with voriconazole. South Med J. 2004;97:1116-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sugimoto Y, Mizutani H, Sato T, Kawamura N, Ohkouchi K, Shimizu M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis with severe gastrointestinal mucosal cell death: a patient who excreted long tubes of dead intestinal epithelium. J Dermatol. 1998;25:533-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Michel P, Joly P, Ducrotte P, Hemet J, Leblanc I, Lauret P, Lerebours E, Colin R. Ileal involvement in toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell syndrome). Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1938-1941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Zweiban B, Cohen H, Chandrasoma P. Gastrointestinal involvement complicating Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Roupe G, Ahlmén M, Fagerberg B, Suurküla M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis with extensive mucosal erosions of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1986;80:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Beck MH, Portnoy B. Severe erythema multiforme complicated by fatal gastrointestinal involvement following co-trimoxazole therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Heye P, Descloux A, Singer G, Rosenberg R, Kocher T. Perforated sigmoid diverticulitis in the presence of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Morelli MS, O'Brien FX. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and cholestatic hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2385-2388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Maggio MC, Liotta A, Cardella F, Corsello G. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and cholestatic hepatitis induced by acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Slim R, Fathallah N, Aounallah A, Ksiaa M, Sriha B, Nouira R, Ben Salem C. Paracetamol-induced Stevens Johnson syndrome and cholestatic hepatitis. Curr Drug Saf. 2015;10:187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Claes P, Wintzen M, Allard S, Simons P, De Coninck A, Lacor P. Nevirapine-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis and toxic hepatitis treated successfully with a combination of intravenous immunoglobulins and N-acetylcysteine. Eur J Intern Med. 2004;15:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Klein SM, Khan MA. Hepatitis, toxic epidermal necrolysis and pancreatitis in association with sulindac therapy. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:512-513. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Limauro DL, Chan-Tompkins NH, Carter RW, Brodmerkel GJ, Agrawal RM. Amoxicillin/clavulanate-associated hepatic failure with progression to Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:560-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Dylewski ML, Prelack K, Keaney T, Sheridan RL. Asymptomatic hyperamylasemia and hyperlipasemia in pediatric patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:292-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 48. | Tagami H, Iwatsuki K. Elevated serum amylase in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:250-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Coetzer M, van der Merwe AE, Warren BL. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a burn patient complicated by acute pancreatitis. Burns. 1998;24:181-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Guégan S, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Roujeau JC, Revuz J. Performance of the SCORTEN during the first five days of hospitalization to predict the prognosis of epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:272-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Tripathi A, Ditto AM, Grammer LC, Greenberger PA, McGrath KG, Zeiss CR, Patterson R. Corticosteroid therapy in an additional 13 cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a total series of 67 cases. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2000;21:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Metry DW, Jung P, Levy ML. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in children with stevens-johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: seven cases and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1430-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Schneider JA, Cohen PR. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Concise Review with a Comprehensive Summary of Therapeutic Interventions Emphasizing Supportive Measures. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1235-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Huang YC, Li YC, Chen TJ. The efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:424-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |