Published online Sep 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.219

Peer-review started: March 22, 2018

First decision: April 18, 2018

Revised: June 12, 2018

Accepted: June 25, 2018

Article in press: June 27, 2018

Published online: September 16, 2018

Processing time: 179 Days and 13.5 Hours

For patients suffering from both biliary and duodenal obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stent placement is the treatment of choice. ERCP through an already existing duodenal prosthesis is an uncommon procedure and furthermore no studies have reported installing a covered metal stent onto an already existing bare metal stent in the common bile duct (CBD). We describe a rare case of a stent-in-stent dilatation of the CBD through an already existing self-expanding metal stent in the second part of duodenum for the patient presenting with jaundice in setting of biliary and duodenal obstruction from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The biliary obstruction was relieved with a decrease in bilirubin levels post-stenting.

Core tip: Patients with gastric outlet obstruction from duodenal, ampullary or pancreatic malignancy frequently develop biliary obstruction. These patients usually undergo prophylactic biliary stent placement as the likelihood of developing biliary stricture or obstruction is very high. Here, we present a case of a patient who already had a duodenal and biliary stent which required placement of a covered metal stent into the existing common bile duct prosthesis to relieve his biliary obstructive symptoms.

- Citation: Virk GS, Parsa NA, Tejada J, Mansoor MS, Hida S. Successful stent-in-stent dilatation of the common bile duct through a duodenal prosthesis, a novel technique for malignant obstruction: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(9): 219-224

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i9/219.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.219

Malignant gastric outlet obstructions (GOOs) often present with associated malignant biliary stenosis either on initial presentation or later in the clinical course[1]. Most patients get biliary stenting before having duodenal stents placed as it is difficult to access the papilla through the self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) in the duodenum[2-4] even though recent studies have shown that biliary stenting is feasible with high success rate through the duodenal stent[3,5]. We describe even a rarer case in which the patient already had a bare metal stent (BMS) in the common bile duct (CBD) and SEMS in the duodenum who needed further biliary stenting.

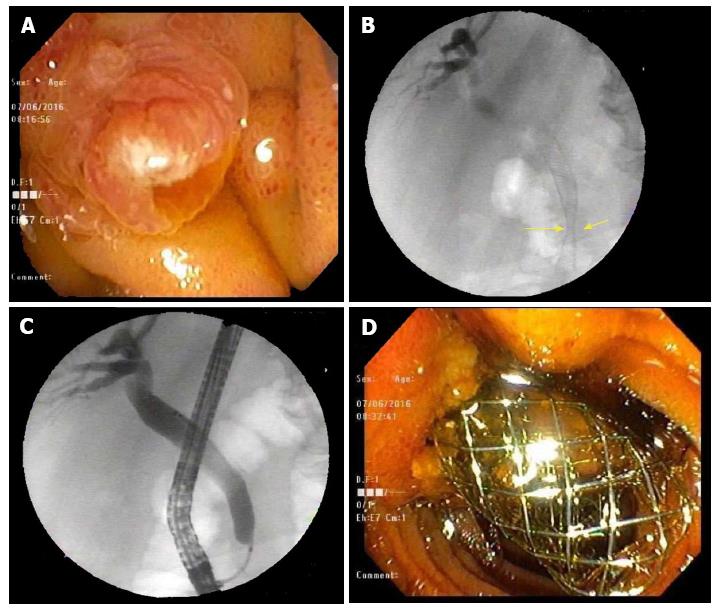

A 78-year-old man presented with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea and emesis. CT imaging showed findings consistent with GOO. A year prior in July 2016 he had presented to our facility with obstructive jaundice secondary to a pancreatic head mass (3 mm × 2 mm) with sonographic evidence suggesting both superior mesenteric artery and portal vein invasion. He underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and successful dilatation of the CBD with the placement of a 10 mm × 6 cm BMS approximately 5 cm into the CBD (Figure 1). Biopsy of the mass confirmed adenocarcinoma.

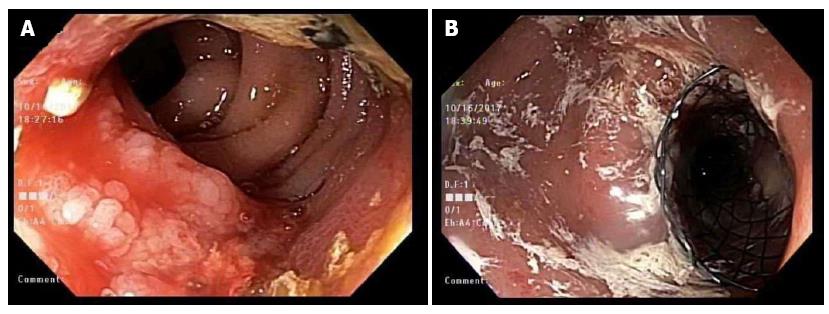

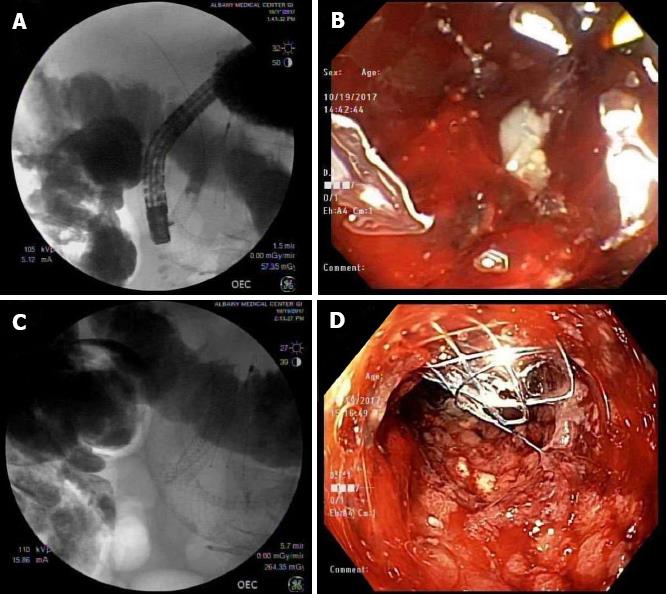

During hospitalization in October 2017, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed retained fluid in the gastric body. There was a malignant appearing, intrinsic moderate stenosis in the second part of the duodenum suggesting type II GOO. The biopsy showed active duodenitis with gastric metaplasia and inflammatory exudates consistent with an ulcer. This area was traversed and stented with a 22 mm × 12 cm WallFlex stent using fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 2). Three days later the patient underwent repeat EGD for acute, new onset jaundice and failure to respond to medical treatment. Endoscopic evaluation showed a patent WallFlex SEMS without any migration. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with fluoroscopy was simultaneously performed and confirmed the previously placed duodenal and biliary stents. The scope was passed through the duodenal stent with precision fluoroscopic guidance and the bile duct containing the previously placed CBD stent (10 mm × 6 cm BMS) was deeply cannulated with the short-nosed traction auto-tome and guidewire. Contrast was injected and ductal flow of contrast was adequate. Contrast extended to the main bile duct; however, the lower third of the main bile duct, the middle third of the main bile duct and CBD was completely obstructed by what appeared to be a mass with tumor ingrowth (the same mass that had eroded and obstructed the duodenum previously). A 0.035-inch × 260 cm straight guidewire (Hydra Jag wire) was passed into the biliary tree. Dilatation of the duodenal stent side was accomplished with a Hurricane 10 mm × 4 cm balloon dilator and was successful. One 10 mm × 4 cm covered metal stent (CMS) was placed 3 cm into the previous 10 mm × 6 cm BMS within the CBD. Bile and clear fluid flowed through the stent and the stent was in proper position (Figure 3). The patient’s total bilirubin dropped from 5.7 to 3.5 the next day. Four days later, his total bilirubin was 1.5, his acute symptoms had resolved and he was discharged from the hospital.

Relevant patient information: BMI 26.6, non-smoker. History: Coronary heart disease and percutaneous coronary intervention, cerebrovascular accident, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary embolism, nonresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma, hypothyroidism, depression and hypertension.

We have seen that patients who have GOO from duodenal, ampullary or pancreatic malignancy frequently develop biliary obstruction which may require either surgical or endoscopic intervention[1]. Usually we can divide patients into any one of the following three categories depending on the chronological order of the obstruction, i.e., biliary obstruction before the duodenal obstruction, concurrent biliary and duodenal obstruction or biliary obstruction after duodenal obstruction. In most cases duodenal obstruction happens later during the disease course[4,6,7]. Further classification can be done based on anatomic location of the duodenal obstruction in relation to the papilla. GOO type I has duodenal obstruction before the papilla, type II involves the papilla and type III is post papilla. GOO-II is the most difficult to manage via endoscopic stenting whereas GOO-III is the easiest to manage[4,6,7].

Before the advancement of endoscopic intervention, biliary bypass surgery was the treatment of choice[8]. With recent advancements in the endoscopic field (such as placement of biliary and duodenal SEMS), safer and more cost-effective ways have emerged to help improve the quality of life of patients who are otherwise not surgical candidates[9].

Typically, patients who present with malignant GOO typically undergo prophylactic biliary stent placement as the likelihood of developing biliary stricture or obstruction is very high; moreover, data in the past has shown that an estimated 60% of patients receiving duodenal stents also end up with biliary stents[2]. For patients who do not undergo biliary stenting (usually placed during the placement of an enteral stent), the gastroenterologist will have to uniquely perform the ERCP through an already existing duodenal stent. Our patient case fell under an even rarer clinical scenario in which not only did the patient have a duodenal stent, but he also had CBD prosthesis. To our knowledge this is the first case of true stent-in-stent placement of a BMS into the CBD through an already existing duodenal and CBD stent.

Studies in the past have explored risk factors and success rates of ERCP biliary metallic stenting in patients with an already existing SEMS due to duodenal obstruction. A study done by Yao et al[10] showed that for malignant duodenal stricture with SEMS, ERCP with biliary metallic stenting was safe and effective. The study showed that 60 mm duodenal stent had ERCP success rate of 88% as compared to longer 80-90 mm stents that had a success rate of 18.2%. Furthermore, type 1 (GOO above the ampulla) and 2 (GOO at the level of ampulla) GOO with stricture length greater than 3.5 cm had lower ERCP success rates than strictures with a length less than 3.5 cm. GOO type 3 (GOO distal to the ampulla) had 100% ERCP success rate. To summarize, a stricture length of > 3.5 cm and duodenal stent length of 80-90 mm were independent risk factors for the failure of ERCP in patients with prior SEMS in the duodenum[10].

A study done by Hamada et al[11] evaluated time to recurrent biliary obstruction (TBRO) in patients who underwent endoscopic biliary drainage combined with a duodenal stent. The median TBRO was 450 d but no information about subsequent intervention was mentioned[11]. Another study done by Moon et al[5] on 8 patients with duodenal and biliary obstruction showed that biliary stenting following a duodenal SEMS is highly successful and feasible but no data was mentioned for patients having persistent biliary obstruction after the abovementioned procedure.

Another way to relieve CBD obstruction is endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD). This is a relatively new technique in which a fistula is made between the biliary duct and intestine[12]. This method has been shown to be equivalent to percutaneous biliary drainage (PTBD) and is used as a salvage procedure after ERCP has failed and can be utilized in patients with or without duodenal stenosis[13,14]. A study done by Dhir et al[14] in patients that failed one or more ERCP attempts revealed that the short-term outcome of EUS-BD were comparable to that of ERCP. Similarly, another study done by Moon et al showed that EUS-BD is a therapeutic option when ERCP approach through the lumen of the duodenal SEMS fails. EUS-BD could be performed through the duodenum or through an existing mesh of a duodenal stent[3].

The treatment of initial malignant biliary stenosis resulting in GOO- II that is alleviated with a duodenal SEMS is the most common scenario of biliary and duodenal obstruction intervention. It is easier to stent the duodenal obstruction after stenting the biliary obstruction but not vice versa[7]; however, Moon et al[3,5] have shown great success in biliary stenting through duodenal stents. In our case, even though the patient had an existent biliary stent, accessing the CBD was difficult due to tumor invasion and bloody debris (Figure 3B). There was zero visualization of the papilla making fluoroscopy the only way to visualize and cannulate the CBD as compared to the naïve papilla (Figure 1A) that is seen during the initial CBD stent placement.

There have been previous studies showing plastic biliary stents that were combined with biliary and duodenal metal stenting[15,16], but to our knowledge, the above studies did not include patients with duodenal SEMS and CBD BMS who required further biliary stenting. Additionally, there are no published guidelines to follow in these scenarios. Our patient had an existing duodenal prosthesis along with a CBD BMS and was still experiencing biliary obstructive symptoms. The placement of the duodenal stent did not affect the patency of the existing CBD BMS. Considering ERCP as the first line therapy, we deployed a CMS on top of the BMS. This technique worked for our patient as a successful palliative and quality of life measure and was without any complications. By the time of hospital discharge, he had clinically improved and his total bilirubin continued to normalize.

While recently published literature has addressed initial stent placed into the CBD through a duodenal prosthesis for biliary obstruction, this is the first known case of inserting a second stent into the previous CBD stent through the duodenal prosthesis. In the future, endoscopists can consider this technique to stent an already existing CBD stent for alleviating malignant biliary obstruction in patients who are otherwise not candidates for surgical intervention. Researchers and clinicians should continue to investigate this modality and future utilization will allow us to identify any new findings or complications associated with this unique technique.

The patient with a bare metal stent (BMS) in the common bile duct (CBD) and self-expanding metal stent (SEMS) in the duodenum presented with worsening jaundice symptoms.

On esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) patient was found to have gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) type II and worsening jaundice due mass obstructing the CBD.

Pancreatic, duodenal or ampullary mass.

Main laboratory testing for a biliary and duodenal obstructing mass would be a tissue biopsy obtained via endoscopic guided technique.

CT scan of the abdomen was used initially to find GOO followed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas was found on biopsy.

Covered metal stent (CMS) was placed into the previous BMS within the CBD through the already existing duodenal SEMS with relief of jaundice symptoms.

To our knowledge other case reports don’t have concomitant BMS in the CBD and SEMS in the duodenum while getting CMS in the CBD stent.

Even though accessing the papilla through an already existing duodenal SEMS and CBD BMS may be difficult, endoscopists can try cannulating the CBD to relieve patient’s obstructive biliary symptoms, and if need deploy another stent.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: Guidelines of the CARE Checklist (2013) have been adopted while writing this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gonzalez-Ojeda AG, Kikuyama M, Rabago LR, Thomopoulos KC S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Adler DG, Baron TH. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Dormann A, Meisner S, Verin N, Wenk Lang A. Self-expanding metal stents for gastroduodenal malignancies: systematic review of their clinical effectiveness. Endoscopy. 2004;36:543-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Moon JH, Choi HJ. Endoscopic double-metallic stenting for malignant biliary and duodenal obstructions. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:658-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Baron TH, Harewood GC. Enteral self-expandable stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:421-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moon JH, Choi HJ, Ko BM, Koo HC, Hong SJ, Cheon YK, Cho YD, Lee MS, Shim CS. Combined endoscopic stent-in-stent placement for malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction by using a new duodenal metal stent (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:772-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Baron TH. Management of simultaneous biliary and duodenal obstruction: the endoscopic perspective. Gut Liver. 2010;4 Suppl 1:S50-S56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mutignani M, Tringali A, Shah SG, Perri V, Familiari P, Iacopini F, Spada C, Costamagna G. Combined endoscopic stent insertion in malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. Endoscopy. 2007;39:440-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Huang JJ, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Surgical palliation of unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma in the 1990s. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:658-66; discussion 666-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Johnsson E, Thune A, Liedman B. Palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction with open surgical bypass or endoscopic stenting: clinical outcome and health economic evaluation. World J Surg. 2004;28:812-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yao JF, Zhang L, Wu H. Analysis of high risk factors for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography biliary metallic stenting after malignant duodenal stricture SEMS implantation. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2016;30:743-748. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hamada T, Nakai Y, Lau JY, Moon JH, Hayashi T, Yasuda I, Hu B, Seo DW, Kawakami H, Kuwatani M. International study of endoscopic management of distal malignant biliary obstruction combined with duodenal obstruction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:46-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Iwashita T, Doi S, Yasuda I. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage: a review. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2014;7:94-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Artifon EL, Aparicio D, Paione JB, Lo SK, Bordini A, Rabello C, Otoch JP, Gupta K. Biliary drainage in patients with unresectable, malignant obstruction where ERCP fails: endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus percutaneous drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:768-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dhir V, Itoi T, Khashab MA, Park DH, Yuen Bun Teoh A, Attam R, Messallam A, Varadarajulu S, Maydeo A. Multicenter comparative evaluation of endoscopic placement of expandable metal stents for malignant distal common bile duct obstruction by ERCP or EUS-guided approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:913-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Novacek G, Pötzi R, Kornek G, Häfner M, Schöfl R, Gangl A, Püspök A. Endoscopic placement of a biliary expandable metal stent through the mesh wall of a duodenal stent. Endoscopy. 2003;35:982-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kaw M, Singh S, Gagneja H. Clinical outcome of simultaneous self-expandable metal stents for palliation of malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:457-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |