Published online Sep 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.210

Peer-review started: May 4, 2018

First decision: June 15, 2018

Revised: July 22, 2018

Accepted: August 2, 2018

Article in press: August 3, 2018

Published online: September 16, 2018

Processing time: 143 Days and 20.2 Hours

To assess the utility of modified Sano′s (MS) vs the narrow band imaging international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) classification in differentiating colorectal polyps.

Patients undergoing colonoscopy between 2013 and 2015 were enrolled in this trial. Based on the MS or the NICE classifications, patients were randomised for real-time endoscopic diagnosis. This was followed by biopsies, endoscopic or surgical resection. The endoscopic diagnosis was then compared to the final (blinded) histopathology. The primary endpoint was the sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of differentiating neoplastic and non-neoplastic polyps (MS II/IIo / IIIa / IIIb vs I or NICE 1 vs 2/3). The secondary endpoints were “endoscopic resectability” (MS II/IIo/IIIa vs I/IIIb or NICE 2 vs 1/3), NPV for diminutive distal adenomas and prediction of post-polypectomy surveillance intervals.

A total of 348 patients were evaluated. The Sn, Sp, PPV and NPV in differentiating neoplastic polyps from non-neoplastic polyps were, 98.9%, 85.7%, 98.2% and 90.9% for MS; and 99.1%, 57.7%, 95.4% and 88.2% for NICE, respectively. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for MS was 0.92 (95%CI: 0.86-0.98); and AUC for NICE was 0.78 (95%CI: 0.69, 0.88). The Sn, Sp, PPV and NPV in predicting “endoscopic resectability” were 98.9%, 86.1%, 97.8% and 92.5% for MS; and 98.6%, 66.7%, 94.7% and 88.9% for NICE, respectively. The AUC for MS was 0.92 (95%CI: 0.87-0.98); and the AUC for NICE was 0.83 (95%CI: 0.75-0.90). The AUC values were statistically different for both comparisons (P = 0.0165 and P = 0.0420, respectively). The accuracy for diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) with high confidence utilizing MS classification was 93.2%. The differentiation of SSA/P from other lesions achieved Sp, Sn, PPV and NPV of 87.2%, 91.5%, 89.6% and 98.6%, respectively. The NPV for predicting adenomas in diminutive rectosigmoid polyps (n = 150) was 96.6% and 95% with MS and NICE respectively. The calculated accuracy of post-polypectomy surveillance for MS group was 98.2% (167 out of 170) and for NICE group was 92.1% (139 out of 151).

The MS classification outperformed the NICE classification in differentiating neoplastic polyps and predicting endoscopic resectability. Both classifications met ASGE PIVI thresholds.

Core tip: Endoscopic differentiation of colorectal polyps can be daunting. Especially with serrated lesions. The Modified Sano’s (MS) classification, the first classification that included sessile serrated adenoma/polyps was developed in 2013. In this randomised controlled trial we compare the accuracies of the well-established narrow band imaging international colorectal endoscopic classification and the MS classification. Although both classifications have met the ASGE PIVI statement thresholds for predicting histology in diminutive rectosigmoid polyps and post-polypectomy surveillance, MS was statistically more accurate.

- Citation: Pu LZCT, Cheong KL, Koay DSC, Yeap SP, Ovenden A, Raju M, Ruszkiewicz A, Chiu PW, Lau JY, Singh R. Randomised controlled trial comparing modified Sano’s and narrow band imaging international colorectal endoscopic classifications for colorectal lesions. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(9): 210-218

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i9/210.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.210

The majority of colorectal polyps are small and benign[1]. Current practice mandates biopsies or removal and pathological interpretation to confirm the diagnosis. With technological advancement in the endoscopy imaging field, the adoption of strategies such as “diagnose, resect and discard” for proximal polyps and “do not resect” for rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps (HPs) has become possible[2,3]. Apart from being cost-effective and perhaps time-efficient, these strategies could potentially reduce the risks of complications associated with polypectomy[4]. For larger lesions, advanced imaging modalities may have a role especially if required to differentiate early cancers confined to the intramucosal layer or infiltrating more than 1000 µm into the submucosa[5-8]. In vivo prediction of colorectal lesions is hence of utmost importance.

Numerous technologies including iScan, flexible spectral imaging colour enhancement (FICE) and narrow band imaging (NBI) have been available to assist in interrogating the surface pattern and microvascular architecture of colorectal polyps. A systematic review comparing standard white light endoscopy, chromoendoscopy and NBI with or without magnification concluded that magnified chromoendoscopy and NBI were the two most accurate modalities in predicting polyp histology[9]. Several studies have demonstrated that NBI is equivalent to chromoendoscopy in distinguishing neoplastic and non-neoplastic colonic polyps. A recent meta-analysis involving 28 studies reported high accuracy with NBI in diagnosing colorectal polyps based on an area under the hierarchical summary receiver-operating characteristic (HSROC) curve of 0.92[10]. Additionally, when high confidence predictions are made, the sensitivity (Sn) and negative predictive value (NPV) exceeded 90%. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) was not considered separately in these studies[10-13].

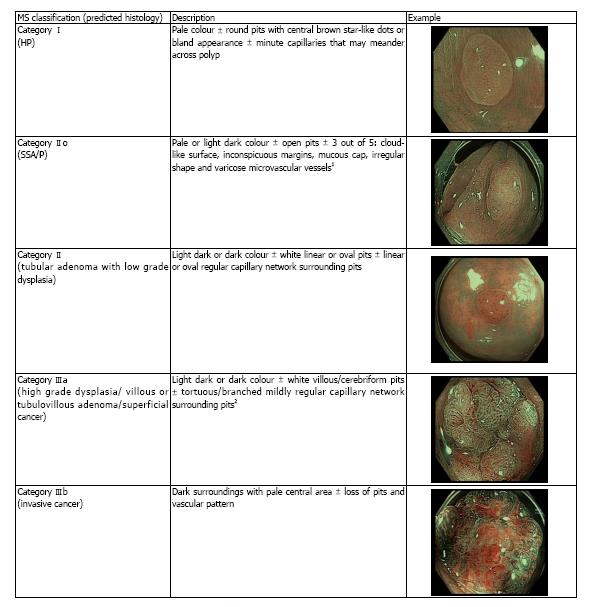

Differentiation of polyps can also be made using NBI with magnified endoscopy (NBI-ME) utilizing various classifications including the Sano’s classification, modified Sano’s (MS) classification, NBI international colorectal endoscopic (NICE), Hiroshima, Showa, Workgroup serrAted Polyps and Polyposis (WASP), JNET and Jikei classifications and 1 published classification for FICE with magnified endoscopy (FICE-ME)[5,11,14-17]. Many of these classifications have been validated in various studies. There are however no comparative data to date on the diagnostic accuracy of these different classifications. Recently the new WASP classification has emerged which included the differentiation of SSA/Ps from HP, but with inconsistent results[18]. The Sano’s classification was modified to include a classification for SSA/P in 2013[19]. As the original Sano’s classification was solely based on capillary pattern, the surface pattern was incorporated in the MS classification, in order to improve its diagnostic capability. The MS classification is defined in accordance with the colour, capillary network surrounding the pit pattern and surface pattern evaluated under magnification. By contrast, the NICE classification of colorectal polyps is based on 3 features including colour, vessel architecture and surface pattern evaluated not necessarily under magnification (Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively). Both the NICE and MS have been found to be independently valid tools for predicting polyp histology according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) statement[5,6,19,20].

| NICE I | NICE II | NICE III | |

| Colour | Same or lighter than background | Browner than background | Dark brown relative to background +/- patchy whiter areas |

| Vessels | None or isolated lacy vessels | Brown vessels surrounding white structures | Disrupted or missing vessels |

| Surface pattern | Dark or white spots of uniform size, or homogeneous absence of pattern | Oval, tubular or branched white structure surrounded by brown vessels | Amorphous or absent surface pattern |

| Likely pathology | Hyperplastic | Adenoma | Deep submucosal invasive cancer |

The ASGE’s PIVI statement[20] regarding colonic polyps has advised thresholds for endoscopic imaging, namely: (1) an endoscopic technology (when used with high confidence) should provide > 90% agreement in determining post-polypectomy surveillance intervals; and (2) the technology (when used with high confidence) should provide > 90% NPV for adenomatous histology for rectosigmoid polyps.

This was introduced to further guide endoscopists using new technologies into achieving measurable outcomes and aiding the incorporation of novel technologies into clinical practice.

There are no randomised trials comparing MS and NICE classifications. The aim of this study is to compare the accuracy of NBI with dual focus (DF) magnification in differentiating colorectal polyps using the NICE and the MS classifications. The NPV for neoplastic prediction (cancer, adenomas and SSA/Ps) within diminutive rectosigmoid polyps and the post-polypectomy surveillance intervals for each classification (based on the ASGE PIVI statement thresholds) was also evaluated.

This study was approved by the Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (TQEH/LMH/MH) and is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (No. NCT02963207). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to colonoscopy. Data were collected at the site of investigation by a research nurse and analysed by a study statistician. Only the endoscopist knew which arm of the trial the patient was on during the endoscopic diagnosis of the lesion. Neither the patient nor the pathologist was aware of the classification used on the lesion.

A concealed container containing 2 cards which randomised the participants to either MS or NICE classifications arm was used. Each week, a research nurse randomly selected a card from the concealed container. This generated allocation was then conveyed to the endoscopist.

All patients undergoing colonoscopy for any indication at the Lyell McEwin Hospital endoscopy unit were evaluated for eligibility by the researchers. Patients were recruited from June 2013 onwards. Inclusion criteria were age of 18 years or older with endoscopic findings of colonic polyps (of any size). Key exclusion criteria included known history of inflammatory bowel disease, familial polyposis syndrome, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, incomplete procedure due to poor bowel preparation or acute angles, current pregnancy and no polyps detected during the procedure.

All colonoscopies were performed by a senior endoscopist with a high level of expertise using the 190 series with DF capability (Exera III NBI system; Olympus Co. Ltd, Japan). This processor allows the NBI image to be enhanced by 150%. The DF function enables magnification of up to 70×. Both are push button techniques and image enhancement with magnification occurs within 1-2 s.

The patients whom had colonic polyps had their polyps assessed in real-time with NBI-DF. DF was used in both groups to standardize the evaluation. The endoscopist studied the lesion carefully at least for one minute. The size of the polyp was estimated by the endoscopist based on the size of the cap (outer diameter of 15 mm) and/or size of the snare/forceps. The polyp was initially examined in white light, then NBI, followed by magnification. Image acquisition was further enhanced with a distal cap attachment to the scope (short transparent cap from Olympus® - D-201, approximately 4 mm from distal end). Efforts were made to obtain a crisp clear still image with water pump and simeticone when needed (no dyes used). Histology in real-time of individual polyps was then predicted using either the NICE or the MS classification, with a confidence level (low/high).

The endoscopist scored each polyp found and the final endoscopic diagnosis was recorded by the research nurse who was present in the endoscopy suite. A clinical judgement was deemed as high in confidence when the endoscopist found a polyp with clear features of one subtype, as described in the classifications shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. If there was any uncertainty or doubt, the prediction was recorded as low confidence. All polyps were photographed and stored for future reference. No video recording was done. This was followed by biopsies and surgical resection in cases of predicted invasive cancer, or endoscopic resection to the remaining lesions. The histopathology was evaluated initially by a non-gastrointestinal (non-GI) specialist pathologist due to personnel limitations. However, if the diagnosis was uncertain the slides were forwarded to a specialist GI pathologist. The pathologists were blinded to the classification used and the prediction of the polyp by the endoscopist. The endoscopy diagnosies was then compared to the final histopathological diagnosis.

The primary endpoint of the study was to prospectively evaluate the Sn, specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV) and NPV of neoplastic (cancer, adenoma or SSA/P) vs non-neoplastic (HP, inflammatory) polyps based on either classification (MS II, IIo, IIIa and IIIb vs MS I or NICE 2, 3 vs NICE 1).

In addition, we assessed the concept of “suitability of endoscopic resection” of these polyps (MS II, IIo, IIIa vs MS I, IIIb or NICE 2 vs NICE 1, 3) and the diagnostic accuracy of SSA/Ps by the MS classification. To assess the ability of the NICE and MS classifications to match the PIVI-1 thresholds, high confidence NBI predictions of polyp histology were given an endoscopy-based surveillance interval. This was then compared with the recommended interval based on histologic assessment. For this calculation, polyps histologically classified as SSA/Ps but classified as NICE 1 or MS I were excluded. This was thought to mitigate bias as NICE has no separate SSA/P classification. As for the PIVI-2 thresholds, we calculated the negative predictive value (NPV) of high confidence NBI predictions for adenomatous histology of diminutive polyps using histology as a reference.

The sample size was calculated based on number of polyps. The primary aim was to test the performance of NBI diagnosis for polyp differentiation. Thus, it was estimated that a total sample size of 560 polyps would be required to have an 80% power with an alpha error of 0.05 to appreciate an increment of 7% in the prediction of histology with the MS classification.

Statistical analysis was performed by using statistical software, Stata 13.0 (StatCorp, TX, United States). Continuous variables are reported as either a mean ± SD or median and range. Means were reported unless the data were nonparametric. The Student’s t test was used to analyse continuous variables, and a Pearson χ2 analysis was used for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P value of 0.05 or less. The analysis applied to the classifications was in regards to the polyps, while the analysis for post-polypectomy surveillance was based on patients.

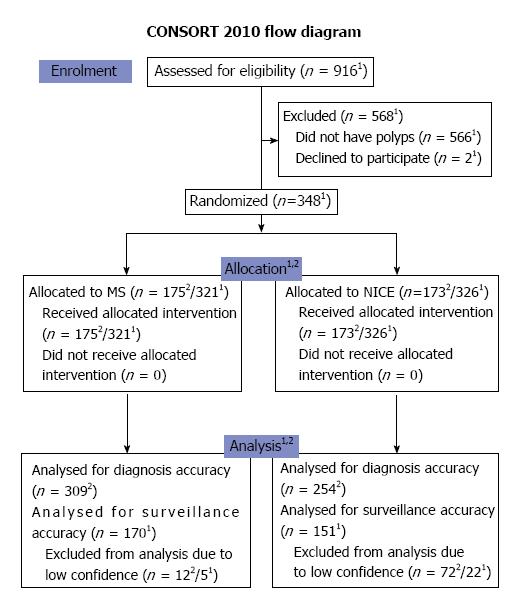

A total of 348 patients were included from June 2013 until June 2015 (Figure 2). The trial was terminated as we have reached the stipulated sample size. Both groups had similar demographics (Table 2). The total number of polyps predicted with high confidence in the MS classification was 309 out of 321 (96.3%). This was significantly higher in proportion as compared to that in the NICE arm (254 out of 326 polyps or 78% - as shown in Table 3). Characteristics of the polyps were not significantly different between both arms except for the mean size of polyps which was larger for the NICE arm (Table 3).

| Classification | Modified Sano’s | NICE | P value |

| age (mean ± SD) | 62.18 ± 14.06 | 64.41 ± 11.36 | NS |

| M:F (% male) | 191:118 (62%) | 178:76 (70%) | NS |

| Indication n (%) | |||

| Screening | 156 (50) | 115 (45) | NS |

| Surveillance | 86 (28) | 88 (35) | |

| Symptoms | 63 (20) | 49 (19) | |

| Others | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Total | 309 | 254 | |

| Classification | Modified Sano’s | NICE | P value |

| Confidence level n (%) | |||

| High | 309 (96.3) | 254 (78) | <0.0001 |

| Low | 12 (3.7) | 72 (22) | |

| Total | 321 | 326 | |

| Distribution based on size | |||

| ≤ 5 mm | 151 | 127 | NS |

| 6-9 mm | 63 | 42 | |

| ≥ 10 mm | 95 | 85 | |

| Size (mean ± SD, mm) | 10.17 ± 11.30 | 14.48 ± 19.47 | 0.0036 |

| Polyp distribution n (%) | |||

| Right colon | 95 (31) | 101 (40) | NS |

| Transverse colon | 60 (19) | 52 (20) | |

| Descending colon | 34 (11) | 27 (11) | |

| Rectosigmoid colon | 120 (39) | 74 (29) | |

| Total | 309 | 254 | |

| Paris n (%) | |||

| 1p | 28 (9) | 18 (7) | NS |

| 1s | 190 (61) | 156 (61) | |

| 2a | 81 (26) | 71 (28) | |

| 2b | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| 2c | 5 (2) | 6 (2) | |

| 3 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| Others | 12 | 15 | |

| Total | 309 | 254 | |

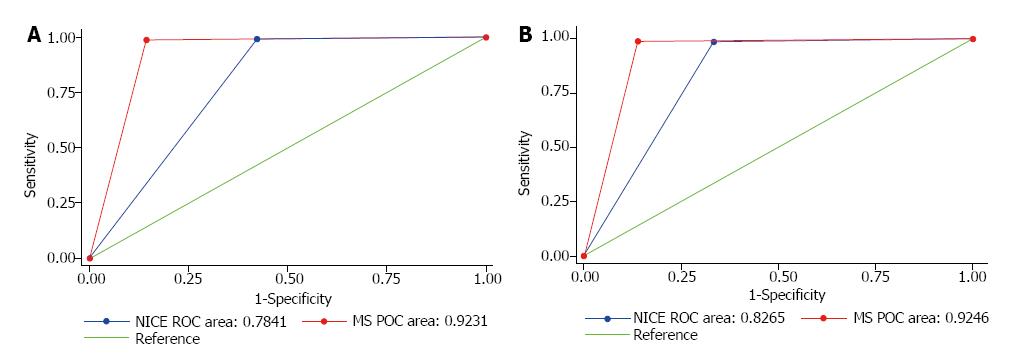

The Sn, Sp, PPV and NPV in differentiating neoplastic from non-neoplastic polyps were 98.9%, 85.7%, 98.2% and 90.9% for MS and 99.1%, 57.7%, 95.4% and 88.2% for NICE respectively. The MS arm had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.92 (95%CI: 0.86-0.98), whilst NICE had an AUC of 0.78 (95%CI: 0.69-0.88). There was a statistically significant difference between the MS and NICE’s AUC values (P = 0.0165) (Figure 3A).

The Sn, Sp, PPV and NPV in predicting ‘endoscopic resectability’ were 98.9%, 86.1%, 97.8% and 92.5% for MS and 98.6%, 66.7%, 94.7% and 88.9% for NICE respectively. The MS group had an AUC of 0.92 (95%CI: 0.87-0.98), whereas NICE had an AUC of 0.83 (95%CI: 0.75, 0.90). There was also a statistically significant difference between the AUC values (P = 0.0420) (Figure 3B).

The accuracy for diagnosis of SSA/P with high confidence using IIo on MS classification was 93.2%, and differentiation of SSA/P from other lesions achieved 87.2% of Sp, 91.5% of Sn, 89.6% of PPV and 98.6% of NPV (Table 4).

| SSA/P | Other histology | |

| MS IIo | 43 (13) | 5 (1.54) |

| Other MS classification | 4 (1.23)1 | 273 (84) |

Classification of polyps according to size is shown in Table 3. Of the high confidence polyps in the MS arm, 150 (48.5%) were diminutive (5 mm or less), 60 (19.5%) were small (6-9 mm) and 99 (32%) were large (≥ 10 mm). In the NICE arm, there were 254 polyps detected with high confidence which included 127 (50%) diminutive, 42 (16.5%) small and 85 (33.5%) large polyps.

The NPV for diminutive rectosigmoid polyps were 96.6% and 95% in MS and NICE arms respectively. The calculated accuracy of post-polypectomy surveillance for MS group was 98.2% (167 out of 170) and for NICE group was 92.1% (139 out of 151).

In the MS arm, there were 20 out 309 (6.4%) high confidence polyps’ inaccuracies. Misdiagnoses which were made were as follows: MS I (3 SSA’s and 1 normal mucosa), MS II (3 normal mucosa, 1 inflammatory polyp, 1 traditional serrated adenoma, 4 tubular adenoma with high grade dysplasia, 1 tubulovillous adenoma with low grade dysplasia and 1 villous adenoma with high grade dysplasia), MS IIo (2 tubular adenoma with low grade dysplasia and 1 HP) and MS IIIa (1 tubular adenoma with low grade dysplasia and 1 villous adenoma with invasive carcinoma).

In the NICE arm, there were 18 out of 254 (7.1%) inaccuracies in high confidence polyps - NICE I (1 normal mucosa, 2 tubular adenomas with low grade dysplasia), NICE II (5 normal mucosa, 5 HPs, 1 inflammatory polyp, 1 focal colitis cystica profunda, 1 cancer) and NICE III (1 tubulovillous adenoma with high grade dysplasia).

These resulted in 10 overcalled and 5 undercalled cases on the in vivo prediction for post-polypectomy surveillance interval (Table 5).

NBI is one of the most easily available and commonly used image-enhanced endoscopic modality. There are many NBI classifications for colorectal lesions, but only two thus far have included SSA/P separately (WASP and MS). The WASP classification was derived from NICE aiming to differentiate HP from SSA/P[18]. The classification does not address the differentiation of adenoma and invasive cancer. A simple, comprehensive and reliable classification is pivotal in clinical practice.

Hewett et al[4] has initially shown NICE subtypes 1 and 2 using non-magnified NBI. The accuracy, Sn and NPV for small colorectal polyps were 89%, 98% and 95%, respectively. The study did not include SSA/Ps. In this study, the MS classification has been proven to be more effective in differentiating neoplastic colorectal polyps (i.e., cancer or adenoma or SSA/P) from non-neoplastic polyps (i.e., inflammatory or HP) when compared to the NICE classification. This is probably attributed to the former’s design which has a sub-division for SSA/Ps. This subdivision may have given the MS classification an upper-hand over the NICE classification as some of the HP misdiagnosed by the NICE were in fact SSA/Ps.

In this study, both NBI classifications were able to meet the PIVI benchmarks as the post-polypectomy surveillance prediction accuracy and NPV for diminutive rectosigmoid polyps exceeded 90% in the two study arms. These findings are compatible with the results of the previous meta-analysis of 20 studies on NBI with and without magnification. The pooled NPV found was 91% for adenomatous histology[21].

SSA/Ps have been recognized as precancerous lesions and they account for up to one third of all sporadic colorectal cancers[22]. They may have been misdiagnosed due to the challenges both endoscopists and pathologists faced in distinguishing them from HPs for the past years.

Several investigators sought to discriminate SSA/Ps from HPs via NBI (without magnification) based on several specific endoscopic features with varying results[23-26]. A recently published prospective study by Yamashina et al[27] reported very high sensitivity (98%) but only modest Sp 59.5% for diagnostic criteria of SSA/Ps through identification of “expanded crypt openings” and “thick branched vessels” on magnified NBI. The WASP classification was not used for comparison in this study as it was only recently published and not available when our study began[18]. Similarly, although the JNET is currently being considered a gold standard in regard to polyp classification (excluding SSA/Ps), this had not been published by the time the study started.

The clinical use of real-time histology is already used in standard practice to evaluate “suitability for resection”. This means that if a lesion is endoscopically considered to be an invasive cancer or if it is predicted to be benign (e.g., distal diminutive HPs), endoscopic resection will not be attempted. Moreover, further benefits of endoscopic diagnosis may add to this “suitability for resection”. Two cost-analysis studies have proven the “diagnose, resect and discard” technique is cost-effective for diminutive polyps[28,29]. There are nevertheless several issues for consideration. For this technique to be adopted globally there should be a standard NBI classification that is easy for inexperienced endoscopists to learn and apply. There is potential risk for litigation if the endoscopists’ histology prediction is inaccurate and with a possibility of patients developing advanced pathology during the inter-surveillance period. In addition, the risk of bleeding and perforation associated with polypectomy may be increased if the endoscopist ‘overcalled’ any lesion. The MS classification could step in to allow these techniques with the more accurate up-to-date endoscopic diagnosis classification.

This study has limitations. All procedures were performed by a single expert. This may not be generalizable. Although other studies within our centre have validated the usefulness of the MS classification compared to NICE and JNET[30], studies utilizing the MS classification must be performed in other endoscopy centres by experts and non-experts to evaluate its reproducibility. The group randomization process used (per week instead of per patient) was not conventional and could have contributed to uneven distribution among both arms. However, this was not translated in demographic differences (Table 2). The reason for doing so was to mitigate possible confusion on which classification should be used for each patient and in order to allow a consistent mental focus on one classification at a time.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the MS classification was superior in differentiating non-neoplastic from neoplastic polyps and more accurately guided the endoscopic resection when compared to the NICE classification. MS is also accurate for predicting SSA/P histology, a subtype neglected by NICE. Nevertheless, both classifications met PIVI thresholds in managing diminutive polyps and determining post-polypectomy surveillance period.

Prediction of polyp histology may prevent unnecessary polypectomies and reduce cost.

The endoscopic differentiation of benign and malignant polyps is sometimes difficult, especially when looking into serrated lesions. Very few endoscopic classifications include the differentiation of sessile serrated lesions [e.g., modified Sano’s (MS)]. These have not being widely used partially due to lack of reliable comparison with the currently used classifications [e.g., narrow band imaging international colorectal endoscopic (NICE)]. The comparison of established classifications with a classification including serrated polyps’ differentiation in a randomised trial could help to support the use of the newer and more comprehensive classifications.

The main objective of this randomised controlled trial is to compare the established adenoma vs non-adenoma NICE classification and the newer neoplastic vs non-neoplastic MS classification.

This was a single centre randomised controlled trial (pathologist blinded) comparing the NICE classification with the MS classification for the endoscopic prediction of histology of colorectal lesions during colonoscopy.

MS classification had significantly higher proportion of high confidence diagnoses compared to NICE. Overall, the MS area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was 0.92 and NICE AUC was 0.78 (P = 0.0165). For predicting “endoscopic resectability”, MS AUC was also 0.92 and NICE AUC was 0.83 (P = 0.0420). The accuracy for diagnosis of SSA/P by MS classification was 93.2%. The NPV for diminutive rectosigmoid polyps were 96.6% and 95% in MS and NICE arms respectively. The calculated accuracy of post-polypectomy surveillance was 98.2% for MS and 92.1% for NICE. Utilizing MS, 6.4% of high confidence polyps were misdiagnosed. Utilizing NICE, 7.1% were misdiagnosed.

The MS classification has shown to be accurate in diagnosing colorectal lesions including sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. Both classifications surpassed the ASGE PIVI thresholds. MS classification may currently be the most accurate and comprehensive endoscopic classification for differentiation of colorectal polyps.

The use of classifications that incorporate the differentiation of serrated polyps such as the MS classification may be necessary. These should become the standard for adequate characterization of colorectal lesions. Nonetheless validation in different centres is required.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: El-Atrebi KEAR, Horesh N, Ishaq S, Mohamed SY, Serban ED S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Bond JH. Polyp guideline: diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance for patients with colorectal polyps. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3053-3063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rastogi A, Rao DS, Gupta N, Grisolano SW, Buckles DC, Sidorenko E, Bonino J, Matsuda T, Dekker E, Kaltenbach T. Impact of a computer-based teaching module on characterization of diminutive colon polyps by using narrow-band imaging by non-experts in academic and community practice: a video-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:390-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ladabaum U, Fioritto A, Mitani A, Desai M, Kim JP, Rex DK, Imperiale T, Gunaratnam N. Real-time optical biopsy of colon polyps with narrow band imaging in community practice does not yet meet key thresholds for clinical decisions. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:81-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hewett DG, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, Tanaka S, Saunders BP, Ponchon T, Soetikno R, Rex DK. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:599-607.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ikematsu H, Matsuda T, Emura F, Saito Y, Uraoka T, Fu KI, Kaneko K, Ochiai A, Fujimori T, Sano Y. Efficacy of capillary pattern type IIIA/IIIB by magnifying narrow band imaging for estimating depth of invasion of early colorectal neoplasms. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Hewett DG, Kaltenbach TR, Sano Y, Ponchon T, Saunders BP, Rex DK, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic prediction of deep submucosal invasive carcinoma: validation of the narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:625-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakadoi K, Tanaka S, Kanao H, Terasaki M, Takata S, Oka S, Yoshida S, Arihiro K, Chayama K. Management of T1 colorectal carcinoma with special reference to criteria for curative endoscopic resection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1057-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kitajima K, Fujimori T, Fujii S, Takeda J, Ohkura Y, Kawamata H, Kumamoto T, Ishiguro S, Kato Y, Shimoda T. Correlations between lymph node metastasis and depth of submucosal invasion in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma: a Japanese collaborative study. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:534–543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Subramaniam V, Mannath J, Hawkey CJ, Ragunath K. Utility of Kudo Pit Pattern for Distinguishing Adenomatous from Non Adenomatous Colonic Lesions In Vivo: Meta-Analysis of Different Endoscopic Techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB277. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | McGill SK, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP, Soetikno RM, Kaltenbach T. Narrow band imaging to differentiate neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps in real time: a meta-analysis of diagnostic operating characteristics. Gut. 2013;62:1704-1713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chiu HM, Chang CY, Chen CC, Lee YC, Wu MS, Lin JT, Shun CT, Wang HP. A prospective comparative study of narrow-band imaging, chromoendoscopy, and conventional colonoscopy in the diagnosis of colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 2007;56:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wada Y, Kashida H, Kudo SE, Misawa M, Ikehara N, Hamatani S. Diagnostic accuracy of pit pattern and vascular pattern analyses in colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Su MY, Hsu CM, Ho YP, Chen PC, Lin CJ, Chiu CT. Comparative study of conventional colonoscopy, chromoendoscopy, and narrow-band imaging systems in differential diagnosis of neoplastic and nonneoplastic colonic polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2711-2716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tanaka S, Sano Y. Aim to unify the narrow band imaging (NBI) magnifying classification for colorectal tumors: current status in Japan from a summary of the consensus symposium in the 79th Annual Meeting of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. Dig Endosc. 2011;23 Suppl 1:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yoshida N, Naito Y, Kugai M, Inoue K, Uchiyama K, Takagi T, Ishikawa T, Handa O, Konishi H, Wakabayashi N. Efficacy of magnifying endoscopy with flexible spectral imaging color enhancement in the diagnosis of colorectal tumors. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:65-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Saito S, Tajiri H, Ohya T, Nikami T, Aihara H, Ikegami M. Imaging by Magnifying Endoscopy with NBI Implicates the Remnant Capillary Network As an Indication for Endoscopic Resection in Early Colon Cancer. Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:242608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Uraoka T, Saito Y, Ikematsu H, Yamamoto K, Sano Y. Sano’s capillary pattern classification for narrow-band imaging of early colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc. 2011;23 Suppl 1:112-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | IJspeert JE, Bastiaansen BA, van Leerdam ME, Meijer GA, van Eeden S, Sanduleanu S, Schoon EJ, Bisseling TM, Spaander MC, van Lelyveld N, Bargeman M, Wang J, Dekker E; Dutch Workgroup serrAted polypS & Polyposis (WASP). Development and validation of the WASP classification system for optical diagnosis of adenomas, hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016;65:963-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singh R, Jayanna M, Navadgi S, Ruszkiewicz A, Saito Y, Uedo N. Narrow-band imaging with dual focus magnification in differentiating colorectal neoplasia. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 2:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rex DK, Kahi C, O’Brien M, Levin TR, Pohl H, Rastogi A, Burgart L, Imperiale T, Ladabaum U, Cohen J. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:419-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 463] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | ASGE Technology Committee. Abu Dayyeh BK, Thosani N, Konda V, Wallace MB, Rex DK, Chauhan SS, Hwang JH, Komanduri S, Manfredi M, Maple JT, Murad FM, Siddiqui UD, Banerjee S. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:502.e1-502.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Batts KP, Burke CA, Burt RW, Goldblum JR, Guillem JG, Kahi CJ, Kalady MF. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1315-29; quiz 1314, 1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 825] [Cited by in RCA: 830] [Article Influence: 63.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kumar S, Fioritto A, Mitani A, Desai M, Gunaratnam N, Ladabaum U. Optical biopsy of sessile serrated adenomas: do these lesions resemble hyperplastic polyps under narrow-band imaging? Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:902-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tadepalli US, Feihel D, Miller KM, Itzkowitz SH, Freedman JS, Kornacki S, Cohen LB, Bamji ND, Bodian CA, Aisenberg J. A morphologic analysis of sessile serrated polyps observed during routine colonoscopy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1360-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, van Eeden S, Tytgat KM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:916-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Singh R, Nordeen N, Mei SL, Kaffes A, Tam W, Saito Y. West meets East: preliminary results of narrow band imaging with optical magnification in the diagnosis of colorectal lesions: a multicenter Australian study using the modified Sano’s classification. Dig Endosc. 2011;23 Suppl 1:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Aoi K, Matsuura N, Nagai K, Matsui F, Ito T, Fujii M, Yamamoto S. Diagnostic features of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps on magnifying narrow band imaging: a prospective study of diagnostic accuracy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:117-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Hassan C, Pickhardt PJ, Rex DK. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:865-869, 869.e1-869.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kessler WR, Imperiale TF, Klein RW, Wielage RC, Rex DK. A quantitative assessment of the risks and cost savings of forgoing histologic examination of diminutive polyps. Endoscopy. 2011;43:683-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zorron Cheng Tao Pu L, Koay DSC, Ovenden A, Burt AD, Singh R. Prospective study predicting histology in colorectal lesions: Interim analysis of the NICE, JNET and MS classifications. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:252. [DOI] [Full Text] |