Published online Sep 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.175

Peer-review started: March 17, 2018

First decision: April 11, 2018

Revised: May 22, 2018

Accepted: June 13, 2018

Article in press: June 13, 2018

Published online: September 16, 2018

Processing time: 184 Days and 14.9 Hours

The progression of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in patients who are taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has been reported by several investigators, leading to concerns that PPI therapy does not address all aspects of the disease. Patients who are at risk of progression need to be identified early in the course of their disease in order to receive preventive treatment. A review of the literature on GERD progression to Barrett’s esophagus and the associated physiological and pathological changes was performed and risk factors for progression were identified. In addition, a potential approach to the prevention of progression is discussed. Current evidence shows that GERD can progress; however, patients at risk of progression may not be identified early enough for it to be prevented. Biopsies of the squamocolumnar junction that show microscopic intestinalization of metaplastic cardiac mucosa in endoscopically normal patients are predictive of future visible Barrett’s esophagus, and an indicator of GERD progression. Such changes can be identified only through biopsy, which is not currently recommended for endoscopically normal patients. GERD treatment should aim to prevent progression. We propose that endoscopically normal patients who partially respond or do not respond to PPI therapy undergo routine biopsies at the squamocolumnar junction to identify histological changes that may predict future progression. This will allow earlier intervention, aimed at preventing Barrett’s esophagus.

Core tip: A review of the literature on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) progression and the associated physiological and pathological changes was performed. Current evidence shows that GERD can progress; however, patients at risk of progression may not be identified early enough for it to be prevented. We propose that endoscopically normal patients who partially respond or do not respond to PPI therapy undergo routine biopsies at the squamocolumnar junction to identify histological changes that may predict future progression. This will allow earlier intervention, aimed at preventing Barrett’s esophagus.

- Citation: Labenz J, Chandrasoma PT, Knapp LJ, DeMeester TR. Proposed approach to the challenging management of progressive gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(9): 175-183

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i9/175.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.175

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been defined as a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus causes troublesome symptoms such as heartburn and/or regurgitation[1]. This primarily symptomatic definition is not a precise guide to the objective presence of disease. There is not always a clear correlation between reflux symptoms and objective evidence of the disease such as esophagitis or increased esophageal acid exposure on 24-h pH monitoring. Patients may have typical reflux symptoms in the absence of endoscopic esophagitis [referred to as non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)][1], or endoscopic esophagitis in the absence of typical reflux symptoms[2,3]. In both situations, a 24-h esophageal pH monitoring study is required to confirm the presence of the disease.

In practice, it is common for primary care physicians to initiate treatment with a trial of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in patients with symptoms of GERD. If symptoms are relieved, the diagnosis of GERD is confirmed. However, studies have shown that the PPI trial has a limited ability to identify GERD, particularly if the patient presents with atypical symptoms[4,5]. In the absence of a complete response to PPI treatment, the PPI dose is usually doubled[6]. If this does not lead to symptom resolution, a 24-h pH study, with or without impedance, should be performed in the absence of PPI treatment to determine whether or not the patient has GERD. Further increase in PPI dose or prescription of an alternative PPI is recommended in the event of a positive GERD diagnosis following pH monitoring[6]. This approach to the diagnosis and treatment of GERD has popularized the notion that patients whose symptoms persist under PPI therapy have not received a sufficiently high dose. The possibility of progression of GERD under PPI therapy is not commonly considered by physicians. Despite this, progression of GERD under therapy has been demonstrated by several clinical investigators[7-10], and has raised concern that PPI treatment may not address all aspects of the disease. The pathology of early disease is not fully understood because endoscopy is indicated only when PPI treatment is ineffective, and biopsy is not recommended in patients who appear endoscopically normal[6,11]. This may prevent early identification of endoscopic risk factors for visible Barrett’s esophagus (BE), the pre-malignant lesion of esophageal adenocarcinoma[12]. Furthermore, the structure and functional status of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) in patients who have an incomplete response to PPI therapy is rarely evaluated, despite its important role in the disease[7].

Two scenarios have been proposed regarding the natural history of GERD. The first is that GERD can be categorized as either NERD or erosive reflux disease (ERD), and that patients remain in their diagnosed category[13,14]. The second is that GERD is a spectrum disorder, with NERD at one end of the spectrum, and BE and esophageal adenocarcinoma at the other, with the possibility of disease progression over time[9,15]. Current evidence appears to support the hypothesis that GERD is progressive, with several studies showing progression in cohorts of patients with different initial disease categorizations[8,10,15,16].

One of the largest studies of GERD progression (the ProGERD study) involved 2721 patients from Germany, Switzerland, and Austria[8]. Patients were categorized endoscopically as having NERD or ERD, and those with ERD were further categorized based on Los Angeles (LA) classification grades (A-D) at baseline; patients with evidence of BE were excluded from the analysis of progression. Patients underwent an initial endoscopy followed by 4-8 wk of esomeprazole therapy. Maintenance therapy was then provided by each patient’s primary care physician; patients were followed for 5 year during which they underwent repeat endoscopies. Progression to BE (confirmed by endoscopy and biopsy) was observed in 5.9% of patients with NERD, 12.1% of patients with mild-to-moderate ERD (LA grade A/B) and 19.7% of patients with severe ERD (LA grade C/D). Overall, 10% of patients had progressed to BE by the end of the 5-year follow-up period, clearly demonstrating disease progression in a proportion of patients receiving PPI therapy. This study also established that although the treatment of GERD with PPIs can improve symptoms and heal erosive esophagitis, it does not appear to prevent progression to BE.

Pace et al[15] reported data from a study of 33 patients with NERD who were referred to a gastrointestinal clinic in Milan, Italy and followed for 10 year. Patients were endoscopically normal but had an abnormal 24-h esophageal pH at baseline (acid exposure > 5%). Within 5 year of a GERD diagnosis, 17 of the 18 patients (94.4%) who underwent endoscopy had esophagitis. All of the patients were taking PPIs, either at the recommended dose (11/18) or at half the recommended dose (7/18). When active therapy was discontinued during follow-up, symptoms of GERD returned in 96.6% of available patients [median follow-up time 10 year (range 7-14 year)]. This study demonstrated that NERD is a chronic disease that can progress in severity over time in patients taking PPIs, and therefore requires protracted medical therapy. It further demonstrated that the absence of endoscopic esophagitis at presentation is not a positive prognostic factor.

GERD progression in patients undergoing PPI therapy has been shown to be related to a defective LES. In a study of 40 Swedish patients with GERD (confirmed by increased esophageal acid exposure on 24-h pH monitoring) who were treated with PPIs and followed up for 21 year, progression to BE occurred in 45% of patients (18/40)[7]. Manometric evaluation of the LES was performed at the beginning of the study and at the end of the follow-up period. Progression was associated with a significant reduction in mean intra-abdominal LES length on manometry (P = 0.01) and significantly greater esophageal acid exposure on pH monitoring (P = 0.004) than was observed in patients who did not experience disease progression. Furthermore, a trend towards increased use of PPIs and an increase in the number of patients who developed erosive esophagitis was observed over the 21-year period. These results implied that patients with a long duration of GERD were at risk of progression despite PPI treatment and that this was likely to be due to deterioration of the LES during the course of therapy. This study was the first to introduce this concept, which has since led to the prospective examination of LES function prior to PPI therapy in patients with GERD.

The concept that PPI efficacy decreases with increased damage to the LES, and with increased compromise in esophageal body function, has been corroborated in a prospective study of patients with GERD[17]. In this study, a defective LES was defined as LES pressure of less than 8 mmHg and/or abdominal length of less than 1.2 cm. If more than 20% of peristaltic contractions were ineffective, the esophageal body was regarded as being compromised. PPI failure, shown by the recurrence of symptoms or esophagitis, was reported in 7.7% of patients (2/26) with a normal LES and normal esophageal body, 38.1% of patients (24/63) with a defective LES and normal esophageal body, and 79.5% of patients (31/39) with a defective LES and a compromised esophageal body. These results strongly indicated that PPI therapy is less effective in patients with a defective LES than in those with a normal LES, and that a compromised esophageal body contributes further to PPI inefficacy.

In an effort to further understand the mechanical factors implicated in GERD progression, Lord et al[18] investigated the effects of distorted hiatal anatomy, the manometric condition of the LES, and esophageal exposure to acid and bile, on GERD severity. The study population comprised 39 patients with NERD, 42 patients with mild ERD (esophagitis that was healed with PPI therapy), 35 patients with severe ERD (esophagitis that persisted despite PPI therapy), and 44 patients with BE. All patients were taking PPIs prior to subsequent surgical treatment. Patients with severe ERD or BE had a significantly higher prevalence of distorted hiatal anatomy, a defective LES, and esophageal acid exposure. Esophageal bile exposure was significantly higher in patients with BE than those with NERD, mild ERD or severe ERD. The significant anatomical and physiological differences between patients with mild ERD and those with severe ERD are indicative of differences in the mechanical properties of the antireflux barrier. Variability in PPI dose is therefore not the only contributing factor to GERD severity, and treatment with PPIs is unlikely to prevent progression in patients with advanced abnormalities in hiatal anatomy and LES function; major antireflux surgery is usually required in such patients. Where PPIs are ineffective, early intervention with an LES augmentation procedure may prevent progression to severe ERD, and obviate the requirement for major antireflux surgery.

The most important information gained from the aforementioned studies is that treatment with PPIs does not prevent progression to BE in a proportion of patients, and that damage to the LES is significantly more prevalent in these patients compared with those whose disease does not progress. These findings encourage the identification of individuals at risk of GERD progression through manometric evaluation of LES function and 24-h esophageal pH monitoring. These patients may be candidates for a surgical procedure to improve LES function that may, consequently, improve PPI efficacy[18].

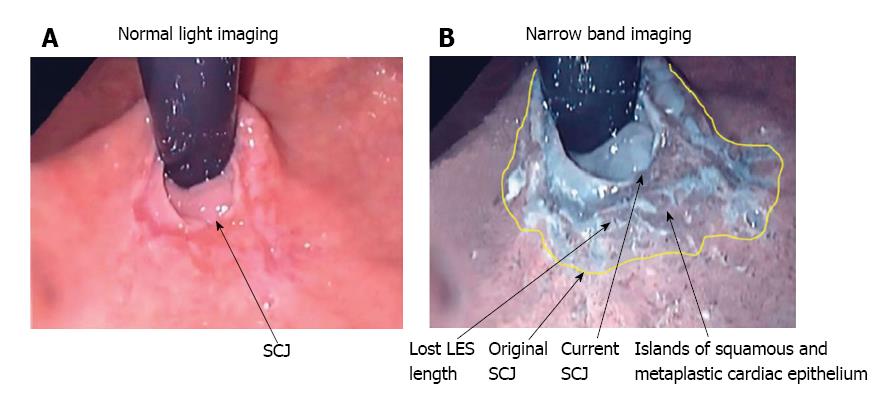

Upper endoscopy is recommended in patients with atypical symptoms who do not respond to PPI therapy[6]. Narrow band imaging (NBI), which enhances the contrast between the esophageal mucosa and the gastric mucosa, has improved visualization of the morphology of the squamo-columnar junction (SCJ) (Figure 1) and been demonstrated to improve the endoscopic diagnosis of GERD. In a study of 107 patients with NERD (n = 36), ERD (n = 41) or no disease (n = 30), which compared conventional endoscopy with NBI, micro-erosions, increased vascularity, and pit patterns at the SCJ were clearly visible using NBI, but were not visible using conventional endoscopy[19]. Furthermore, NBI proved useful in distinguishing patients with NERD from healthy individuals. NBI is not expected to replace conventional endoscopy in the diagnosis of GERD; however, it can be useful for differentiating patients with NERD from patients with ERD, and for grading patients with ERD, and can therefore help to identify patients with severe disease who may be at risk of progression.

Ambulatory reflux monitoring can confirm the presence of GERD in patients with normal endoscopy and atypical symptoms[20,21]. The primary outcome of a 24-h pH monitoring study is the acid exposure time. Wireless pH monitoring allows the extension of the study time beyond 24 h, which has been demonstrated to increase the diagnostic yield[22]; however, wireless monitoring is expensive and therefore not widely available[21]. An alternative is pH-impedance monitoring, which is considered the gold standard[21]. This method detects all reflux (liquid, gas or mixed) regardless of acidity, and defines the direction of flow. A recent study investigated the potential of pH-impedance monitoring to predict symptomatic outcome over a 5-year period in 94 patients with GERD who were not taking PPIs. The investigators reported that phenotyping of GERD according to the strength of evidence of reflux from pH-impedance testing efficiently stratified symptomatic outcome, and could be useful in planning disease management[23]. In a study of GERD progression, patients with progressive disease had significantly increased esophageal acid exposure than those whose disease did not progress[7]. pH-impedance monitoring may therefore be useful in the identification of patients who may be at risk of progression.

Conventional water-perfused manometry and, more recently, high resolution manometry (HRM) are used to evaluate LES and esophageal body function in patients with GERD. The technical advantages of HRM include its high density of recording sites, advanced solid-state sensor technology, and sophisticated plotting algorithms, as well as its superior speed and ease of performance compared with conventional manometry[21,24]. However, a recent study comparing conventional manometry with HRM in the assessment of the LES in 55 patients with foregut symptoms, reported no difference between the two techniques in their measurement of resting LES pressure[24]. Furthermore, LES overall and abdominal length were consistently overestimated by HRM compared with conventional manometry. Consequently, HRM could limit the detection of LES abnormalities, leading to difficulties in the identification of LES abnormalities as a cause for PPI inefficacy.

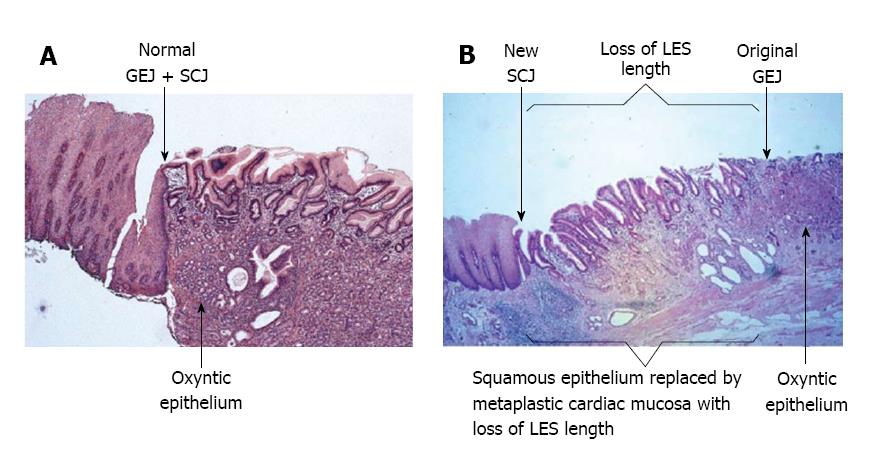

The identification of factors associated with progression to BE and the need for surgical intervention, are key to managing those patients whose disease is progressive. This requires an understanding of the pathophysiology and pathology of GERD. Physiological and pathological studies have introduced the concept that GERD begins at the SCJ. In the absence of squamous epithelial injury, the SCJ and the gastroesophageal junction are concordant[11,25]. As squamous epithelial injury occurs, metaplastic cardiac epithelium forms and the SCJ separates from the gastroesophageal junction and moves upwards into the esophagus. This process causes damage to the LES, resulting in greater esophageal exposure to acid and bile.

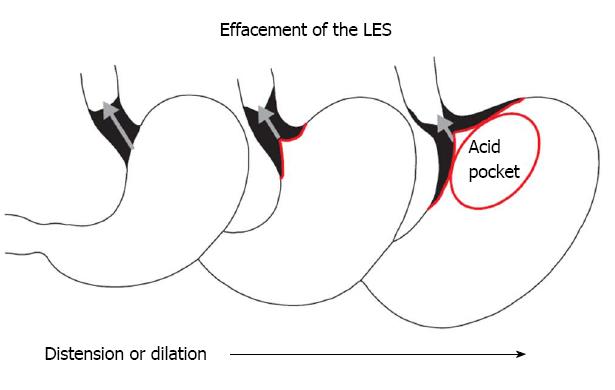

A normal LES occupies the entire abdominal esophagus and a small portion of the thoracic esophagus, and is lined with squamous epithelium. Gastric distension or postprandial non-pressurized gastric dilation causes transient effacement of the distal LES into the stomach (Figure 2)[25]. Effacement results in the uptake of the distal portion of the LES by the expanding fundus of the distended stomach. This results in loss of abdominal LES length and exposure of the squamous epithelium to acidic gastric juice in the acid pocket[26]. The subsequent inflammatory injury to the unprotected squamous epithelium results in metaplasia of the squamous epithelium to cardiac epithelium (Figure 1)[25,27]. Indeed, biopsies of the SCJ from 714 symptomatic patients with GERD who were endoscopically normal showed that in an acidic environment, the acid-damaged squamous epithelium heals by forming cardiac epithelium[11]. In an additional study of 334 patients with GERD symptoms and no visible evidence of BE, biopsies of the SCJ showed cardiac epithelium in 246 patients (73.7%)[27]. When present, cardiac epithelium was significantly associated with increased esophageal acid exposure, a structurally defective LES, and erosive esophagitis (Table 1). Strikingly, inflammation in the form of carditis was present in 237/246 patients (96%) and was associated with a significantly shorter LES, significantly lower LES pressure, and a significantly higher prevalence of a structurally defective LES than no carditis (Table 2)[27]. Individuals who had both carditis and esophagitis had a significantly greater prevalence of a structurally defective LES and greater esophageal acid exposure than individuals with carditis alone (Table 3)[27].

| Findings on multiple biopsies of the GEJ | |||

| No cardiac epithelium (n = 88) | Cardiac epithelium (n = 246) | P | |

| % time pH < 4 | 1.1 ± 4.6 | 6.0 ± 7.4 | < 0.01 |

| % hiatal hernia | 25 | 55.1 | < 0.01 |

| LES pressure (mmHg) | 13.2 ± 12.8 | 8.0 ± 8.0 | < 0.01 |

| LES abdominal length (mm) | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.2 | < 0.01 |

| LES overall length (mm) | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 1.6 | < 0.01 |

| % defective LES | 27.2 | 62.3 | < 0.01 |

| % esophagitis | 11.2 | 33.2 | < 0.01 |

| Findings on multiple biopsies of the GEJ | |||

| No carditis (n = 9) | Carditis (n = 237) | P | |

| % time pH < 4 | 3.1 ± 4.5 | 6.1 ± 7.2 | 0.14 |

| LES pressure (mmHg) | 10.6 ± 12.4 | 7.8 ± 8.2 | 0.03 |

| LES abdominal length (mm) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 0 |

| LES overall length (mm) | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 0.02 |

| % defective LES | 11.1 | 63.7 | < 0.01 |

| Carditis | |||

| No erosive esophagitis (n = 155) | Erosive esophagitis (n = 82) | P | |

| % time pH < 4 | 4.1 ± 6.5 | 9.2 ± 7.0 | < 0.01 |

| % hiatal hernia | 44.2 | 78.0 | < 0.01 |

| LES pressure (mmHg) | 10.0 ± 8.8 | 5.6 ± 5.0 | < 0.01 |

| LES abdominal length (mm) | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | < 0.01 |

| LES overall length (mm) | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 1.6 | < 0.06 |

| % defective LES | 54.2 | 81.7 | < 0.01 |

| % intestinal metaplasia | 8.3 | 19.5 | 0.02 |

The presence of metaplastic cardiac mucosa at the SCJ results in the formation of a squamo-oxyntic gap between the oxyntic gastric mucosa in the proximal stomach and the remaining squamous esophageal mucosa within the LES (Figure 3)[28]. The length of the squamo-oxyntic gap has been shown to be directly proportional to the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia (IM) of the cardiac epithelium (i.e., the formation of goblet cells). In a study of 1655 patients with GERD, IM was observed in: 24.3% of patients with a gap shorter than 1 cm; 83.5% of patients with a gap of 1-5 cm; and 100% of those with a gap longer than 5 cm[28]. The authors proposed that the length of the squamo-oxyntic gap could be used as a cellular criterion to diagnose GERD. Furthermore, the length of the gap provides an accurate assessment of GERD severity, and IM of the cardiac epithelium within the gap is the most accurate indicator of disease progression and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

These findings strongly support the concept that GERD starts at the SCJ with acid-induced cardiac metaplasia of the injured and inflamed effaced squamous epithelium of the most distal portion of the LES. This process can result in LES damage. These initial changes are subtle and microscopic, and a patient with early GERD is likely to appear endoscopically normal. A manometric assessment of the LES, measurement of esophageal acid exposure, and biopsies at and below the SCJ are therefore required for these changes to be identified.

In the ProGERD study, 171 patients who were endoscopically normal had microscopic IM on biopsy of the SCJ before any therapy[29]. After the 4-8-wk PPI treatment phase of the study, 128 of these patients had a follow-up endoscopy and biopsy of the SCJ; all had persistent microscopic IM. With continued PPI therapy, and endoscopy and biopsy at 2 and 5 year of follow-up, endoscopically visible BE was seen in 25.8% (33/128) of patients[29]. The implication of this finding is that a biopsy showing microscopic IM at the SCJ in a patient who is endoscopically normal indicates a high risk of progression to visible BE, a precursor to esophageal cancer.

An additional population-based study in Sweden assessed the risk of esophageal cancer in 796492 adults taking maintenance PPIs for different indications in 2005-2012. Of 201744 individuals taking PPIs for GERD, 316 developed esophageal cancer. The reported standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of esophageal cancer in patients with GERD who were taking PPIs was 6.87 (95%CI: 6.13-7.67). Furthermore, the SIRs of esophageal cancer were also increased among individuals without GERD, who used PPIs for indications not associated with any increased risk of esophageal cancer (e.g., individuals taking PPIs due to maintenance treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin). The authors concluded that the long-term use of PPIs is associated with increased risk of esophageal cancer in the absence of other risk factors[30].

Of concern is that the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of GERD recommend endoscopic examination only for patients who have an incomplete response to PPI treatment, and recommend routine biopsy only for those with visible evidence of a columnar-lined esophagus of more than 1 cm in length[6]. The histological and pathological features of early disease have therefore not been investigated. Contrary to these guidelines, we propose that patients who are undergoing endoscopy to investigate an incomplete response to PPI therapy, and who have no visible evidence of a columnar-lined esophagus, undergo a routine biopsy of the SCJ. We hypothesize that in a significant minority of such patients, biopsies of the SCJ will reveal the presence of microscopic IM. Based on the findings of the ProGERD study, these patients are at risk of progression to visible BE and are candidates for early preventive treatment[29]. Our hypothesis will need to be tested in the clinical setting to determine whether potentially progressive disease can be identified through routine biopsy of the SCJ in this subgroup of patients, and whether progression can be prevented through earlier intervention. In addition, the number of biopsies required, the cost-effectiveness, and the associated risk of bleeding[31] must be considered before acceptance of this proposed approach in clinical practice.

Acid suppression therapy is notably effective in patients who have a normal LES but less so in those who have a structurally defective LES[17]. Permanent structural alterations to the LES resulting from repeated effacement and chronic inflammation are difficult to correct without surgical intervention. The likelihood of symptom control and prevention of disease progression in patients with persistent symptoms on PPI therapy is greater if surgical correction of a compromised LES is carried out earlier rather than later. Nissen fundoplication has been demonstrated to prevent BE if performed before it develops, and if the fundoplication remains competent[32,33]. A study of 15 patients with microscopic IM at the SCJ in the absence of endoscopically visible BE showed complete regression of microscopic IM in 73.7% of patients (11/15) following early fundoplication[34]. In a separate control group of 45 patients with endoscopically visible BE, only 4.4% of individuals (2/45) showed regression of BE following fundoplication[34]. Despite the ability of the fundoplication procedure to induce significant regression of microscopic IM and prevent development of visible BE, the associated complications (including, dysphagia, bloating, and the inability to burp or vomit[35]) have discouraged the early use of this approach to prevent progressive disease.

Over the past decade, minimally invasive outpatient LES augmentation procedures have been developed[36-39]. Examples include the implantation of a collar of magnetic beads around the inferior border of the LES to prevent its effacement into the stomach[38]; the delivery of radiofrequency to the LES to reduce LES compliance[36]; neuromodulation of the LES through electrical stimulation to increase LES resting pressure[37]; and incisionless partial fundoplication performed using a flexible endoscope introduced to the stomach via the mouth[39]. Clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of LES augmentation in eliminating reflux symptoms and healing esophagitis in patients with GERD who have an incomplete response to PPI therapy[36,37,39,40]. These procedures avoid the complications associated with Nissen fundoplication, are reversible if required, and may therefore be appropriate for early surgical intervention with the goal of preventing disease progression. The effectiveness of these procedures to induce regression of microscopic IM at the SCJ and prevent progression to endoscopically visible BE and subsequent adenocarcinoma should be investigated in future clinical studies.

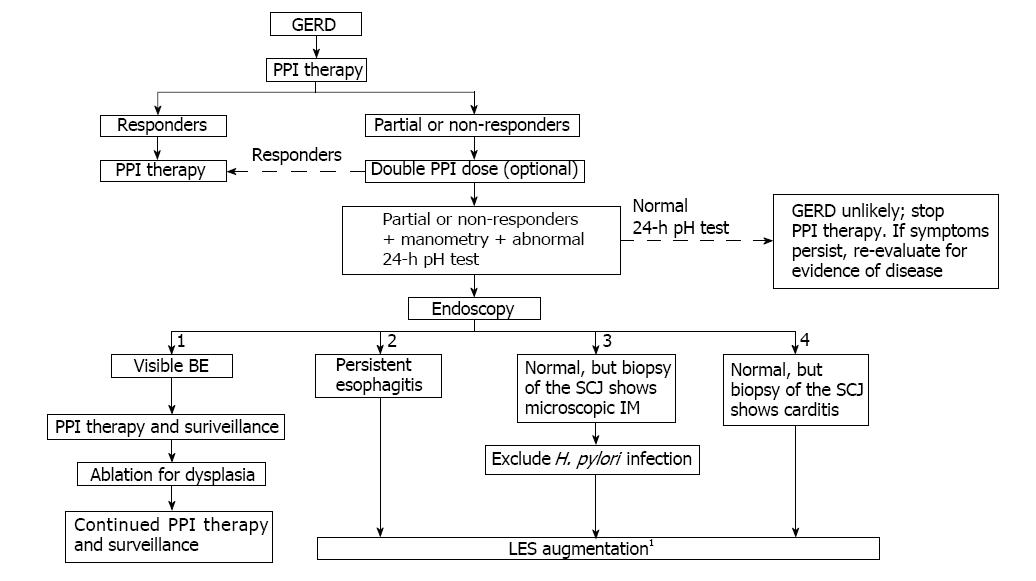

A proposed treatment algorithm that features early use of LES augmentation procedures to prevent GERD progression is shown in Figure 4. The algorithm emphasizes the use of endoscopy, manometry, and esophageal pH monitoring to assess patients with an incomplete response to PPI therapy. Following endoscopy, individuals are stratified into four groups: (1) patients with visible BE; (2) those with persistent esophagitis; (3) those who are endoscopically normal but have microscopic IM of the SCJ (identified by biopsy); and (4) patients who are endoscopically normal but have metaplastic cardiac mucosa with a squamo-oxyntic mucosal gap (identified by biopsy of the SCJ). LES augmentation is recommended for patients in groups (2) and (3) following a manometric evaluation of LES function. LES augmentation for patients in group (4) is only recommended if manometric evaluation reveals a permanently damaged LES. Nissen fundoplication should be considered for patients with extensive damage to the LES after a thorough discussion of the associated complications.

It is important that patients with GERD who are at risk of progression are identified early in the course of their disease in order to prevent the development of BE or other complications. This requires the early use of endoscopy, manometry and esophageal pH monitoring in those with an incomplete response to PPI therapy. In contrast to current management guidelines, we propose routine biopsy of the SCJ in such patients if their esophageal endoscopic evaluation is normal. If microscopic IM is identified, an LES augmentation procedure should be considered with the aim of preventing disease progression to endoscopically visible BE. This proposed approach must first be tested in the clinical research setting to confirm that the encouraging results obtained with the Nissen fundoplication procedure can be reproduced with an LES augmentation procedure.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Tseng PH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2449] [Article Influence: 128.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | DeMeester TR, Peters JH, Bremner CG, Chandrasoma P. Biology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: pathophysiology relating to medical and surgical treatment. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:469-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Graffner H, Vieth M, Stolte M, Engstrand L. High prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and esophagitis with or without symptoms in the general adult Swedish population: a Kalixanda study report. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:275-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bytzer P, Jones R, Vakil N, Junghard O, Lind T, Wernersson B, Dent J. Limited ability of the proton-pump inhibitor test to identify patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1360-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vakil N. Review article: how valuable are proton-pump inhibitors in establishing a diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22 Suppl 1:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308-328; quiz 329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1136] [Cited by in RCA: 1117] [Article Influence: 93.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Falkenback D, Oberg S, Johnsson F, Johansson J. Is the course of gastroesophageal reflux disease progressive? A 21-year follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1277-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Malfertheiner P, Nocon M, Vieth M, Stolte M, Jaspersen D, Koelz HR, Labenz J, Leodolter A, Lind T, Richter K. Evolution of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease over 5 years under routine medical care-the ProGERD study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:154-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pace F, Bianchi Porro G. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a typical spectrum disease (a new conceptual framework is not needed). Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:946-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Vieth M, Agréus L, Aro P. Erosive esophagitis is a risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus: a community-based endoscopic follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1946-1952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chandrasoma P, Wijetunge S, Ma Y, Demeester S, Hagen J, Demeester T. The dilated distal esophagus: a new entity that is the pathologic basis of early gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1873-1881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Campos GM, DeMeester SR, Peters JH, Oberg S, Crookes PF, Hagen JA, Bremner CG, Sillin LF 3rd, Mason RJ, DeMeester TR. Predictive factors of Barrett esophagus: multivariate analysis of 502 patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1267-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Agrawal A, Castell D. GERD is chronic but not progressive. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:374-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fass R, Ofman JJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease--should we adopt a new conceptual framework? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1901-1909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pace F, Bollani S, Molteni P, Bianchi Porro G. Natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease without oesophagitis (NERD)--a reappraisal 10 years on. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Labenz J, Nocon M, Lind T, Leodolter A, Jaspersen D, Meyer-Sabellek W, Stolte M, Vieth M, Willich SN, Malfertheiner P. Prospective follow-up data from the ProGERD study suggest that GERD is not a categorial disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2457-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Klaus A, Gadenstaetter M, Mühlmann G, Kirchmayr W, Profanter C, Achem SR, Wetscher GJ. Selection of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease for antireflux surgery based on esophageal manometry. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1719-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lord RV, DeMeester SR, Peters JH, Hagen JA, Elyssnia D, Sheth CT, DeMeester TR. Hiatal hernia, lower esophageal sphincter incompetence, and effectiveness of Nissen fundoplication in the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:602-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fock KM, Teo EK, Ang TL, Tan JY, Law NM. The utility of narrow band imaging in improving the endoscopic diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Malhotra A, Freston JW, Aziz K. Use of pH-impedance testing to evaluate patients with suspected extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:271-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, Zerbib F, Mion F, Smout AJPM, Vaezi M, Sifrim D, Fox MR, Vela MF. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut. 2018;67:1351-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 942] [Article Influence: 134.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sweis R, Fox M, Anggiansah A, Wong T. Prolonged, wireless pH-studies have a high diagnostic yield in patients with reflux symptoms and negative 24-h catheter-based pH-studies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:419-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Patel A, Sayuk GS, Kushnir VM, Chan WW, Gyawali CP. GERD phenotypes from pH-impedance monitoring predict symptomatic outcomes on prospective evaluation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ayazi S, Hagen JA, Zehetner J, Ross O, Wu C, Oezcelik A, Abate E, Sohn HJ, Banki F, Lipham JC. The value of high-resolution manometry in the assessment of the resting characteristics of the lower esophageal sphincter. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2113-2120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ayazi S, Tamhankar A, DeMeester SR, Zehetner J, Wu C, Lipham JC, Hagen JA, DeMeester TR. The impact of gastric distension on the lower esophageal sphincter and its exposure to acid gastric juice. Ann Surg. 2010;252:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rohof WO, Bennink RJ, Boeckxstaens GE. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the size and acidity of the acid pocket in the stomach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1101-1107.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Oberg S, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Chandrasoma P, Hagen JA, Ireland AP, Ritter MP, Mason RJ, Crookes P, Bremner CG. Inflammation and specialized intestinal metaplasia of cardiac mucosa is a manifestation of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. 1997;226:522-530; discussion 530-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chandrasoma P, Wijetunge S, Demeester SR, Hagen J, Demeester TR. The histologic squamo-oxyntic gap: an accurate and reproducible diagnostic marker of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1574-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Leodolter A, Nocon M, Vieth M, Lind T, Jaspersen D, Richter K, Willich S, Stolte M, Malfertheiner P, Labenz J. Progression of specialized intestinal metaplasia at the cardia to macroscopically evident Barrett’s esophagus: an entity of concern in the ProGERD study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1429-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brusselaers N, Engstrand L, Lagergren J. Maintenance proton pump inhibition therapy and risk of oesophageal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:172-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans J, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fisher L, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:707-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 32. | Nissen R. Gastropexy and “fundoplication” in surgical treatment of hiatal hernia. Am J Dig Dis. 1961;6:954-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gutschow CA, Schröder W, Prenzel K, Bollschweiler E, Romagnoli R, Collard JM, Hölscher AH. Impact of antireflux surgery on Barrett’s esophagus. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387:138-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | DeMeester SR, Campos GM, DeMeester TR, Bremner CG, Hagen JA, Peters JH, Crookes PF. The impact of an antireflux procedure on intestinal metaplasia of the cardia. Ann Surg. 1998;228:547-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kellokumpu I, Voutilainen M, Haglund C, Färkkilä M, Roberts PJ, Kautiainen H. Quality of life following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: assessing short-term and long-term outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3810-3818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 36. | Noar M, Squires P, Noar E, Lee M. Long-term maintenance effect of radiofrequency energy delivery for refractory GERD: a decade later. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2323-2333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Rodríguez L, Rodriguez PA, Gómez B, Netto MG, Crowell MD, Soffer E. Electrical stimulation therapy of the lower esophageal sphincter is successful in treating GERD: long-term 3-year results. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2666-2672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bonavina L, Saino G, Lipham JC, Demeester TR. LINX(®) Reflux Management System in chronic gastroesophageal reflux: a novel effective technology for restoring the natural barrier to reflux. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:261-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Trad KS, Barnes WE, Simoni G, Shughoury AB, Mavrelis PG, Raza M, Heise JA, Turgeon DG, Fox MA. Transoral incisionless fundoplication effective in eliminating GERD symptoms in partial responders to proton pump inhibitor therapy at 6 months: the TEMPO Randomized Clinical Trial. Surg Innov. 2015;22:26-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ganz RA, Peters JH, Horgan S, Bemelman WA, Dunst CM, Edmundowicz SA, Lipham JC, Luketich JD, Melvin WS, Oelschlager BK. Esophageal sphincter device for gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:719-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |