Published online May 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i5.93

Peer-review started: January 4, 2018

First decision: January 22, 2018

Revised: February 20, 2018

Accepted: March 14, 2018

Article in press: March 15, 2018

Published online: May 16, 2018

Processing time: 132 Days and 11.5 Hours

To investigate whether endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided insertion of fully covered self-expandable metal stents in walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) is feasible without fluoroscopy.

Patients with symptomatic pancreatic WOPN undergoing EUS-guided transmural drainage using self-expandable and fully covered self expanding metal stents (FCSEMS) were included. The EUS visibility of each step involved in the transmural stent insertion was assessed by the operators as “visible” or “not visible”: (1) Access to the cyst by needle or cystotome; (2) insertion of a guide wire; (3) introducing of the diathermy and delivery system; (4) opening of the distal flange; and (5) slow withdrawal of the delivery system until contact of distal flange to cavity wall. Technical success was defined as correct positioning of the FCSEMS without the need of fluoroscopy.

In total, 27 consecutive patients with symptomatic WOPN referred for EUS-guided drainage were included. In 2 patients large traversing arteries within the cavity were detected by color Doppler, therefore the insertion of FCSEMS was not attempted. In all other patients (92.6%) EUS-guided transgastric stent insertion was technically successful without fluoroscopy. All steps of the procedure could be clearly visualized by EUS. Nine patients required endoscopic necrosectomy through the FCSEMS. Adverse events were two readmissions with fever and one self-limiting bleeding; there was no procedure-related mortality.

The good endosonographic visibility of the FCSEMS delivery system throughout the procedure allows safe EUS-guided insertion without fluoroscopy making it available as bedside intervention for critically ill patients.

Core tip: The use of self-expanding and lumen-apposing metal stents for the drainage of walled-off necrosis has revolutionised the treatment options and outcome of this disease. Conventionally, these stents are placed by endoscopic ultrasound-guidance but under fluoroscopic control. We could demonstrate that all steps of the stent insertion are visible endosonographically which allows safe and controlled stent placement. Without the need for fluoroscopy and consequent radiation protection regulations, this procedure becomes available in the endoscopy unit and at the bedside of critically ill patients.

- Citation: Braden B, Koutsoumpas A, Silva MA, Soonawalla Z, Dietrich CF. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic walled-off necrosis using self-expanding metal stents without fluoroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(5): 93-98

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i5/93.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i5.93

Endoscopic management by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage and endoscopic necrosectomy has become the preferred treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) after necrotizing pancreatitis as it is minimally invasive and has lower morbidity compared to surgery[1,2]. Pancreatic pseudocysts can be relatively easily drained by insertion of plastic stents but the drainage of WOPN requires large caliber drainage or multi-stenting to empty the necrotic debris and often the remaining necrotic material has to be extracted by endoscopic necrosectomy[3-5]. The use of conventional plastic stents has limitations when treating WOPN because their narrow lumen is often prematurely occluded by necrotic debris[3].

The development of large caliber, specially designed lumen apposing fully covered self-expanding metal stents (FCSEMS) has provided new options for the drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections and improved clinical outcome[4-7].

Previously Rana et al[8] demonstrated that transmural drainage of non-bulging WOPN using plastic stents and nasocystic drains can be safely and effectively achieved non-fluoroscopically by endoscopic ultrasound guidance. The EUS-visibility during EUS-guided placement of metal stents has not been studied previously. However, the avoidance of radiation exposure and fluoroscopy would improve the availability of this outcome changing procedure for critically ill patients as it could be performed at the bedside.

Therefore, in this two-center, single arm study we investigated whether the transmural insertion of FCSEMS for large caliber drainage of WOPN is safely possible by EUS guidance only, avoiding fluoroscopy. For this purpose, we aimed to assess the EUS-visibility of all procedural steps that are required for EUS-guided transmural insertion of FCSEMS.

From May 2014 we started a prospectively maintained database to audit clinical outcome of EUS-guided therapy of pancreatic fluid collections. EUS-guided transmural drainage of walled-off necrosis by FCSEMS insertion performed between May 2014 and August 2017 were analysed. Participating centers were the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, United Kingdom and the Caritas Hospital in Bad Mergentheim, Germany.

The observational nature of the study was established with the respective Health Research Authority and Trust R and D department. The study was therefore registered locally in accordance with Trust clinical governance guidelines. All authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Patients underwent EUS-guided FCSEMS insertion only if computed tomography or MRCP had confirmed WOPN based on the revised Atlanta classification[9] and the patients were symptomatic due to gastric outlet obstruction or biliary obstruction, or ongoing infection and fever despite intravenous antibiotic therapy. EUS-guided transluminal drainage of the pancreatic collection was performed at least four weeks after onset of pancreatitis to allow for sufficient demarcation of the necrotic tissue. Patients were informed in detail about the risks and benefits of the endoscopic treatment and surgical and endoscopic alternatives. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before the endoscopic procedure.

Using a linear scanning therapeutic echoendoscope (EG 3870 Pentax Inc., Tokyo, Japan) EUS-guided drainage was performed in the endoscopy unit under endotracheal intubation and monitoring by an anaesthetic team. Doppler guidance was used to avoid intervening blood vessels and the optimal site for transmural access was selected giving the closest distance between necrotic fluid collection and the gastroduodenal lumen. Transmural access into the WOPN was achieved using a cystotome (Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, United States) or directly the Hot AxiosTM electrocautery system (Xlumena Inc., Mountain View, CA, United States).

A 0.035-inch guidewire was advanced under EUS-guidance and coiled at least twice into the cavity to stabilize the position. The new tract was enlarged using the diathermy of the cystotome or the AxiosTM electrocautery system before the stent delivery system (AxiosTM or NAGITM stent, TaeWoong Medical, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea) was introduced over the guidewire. For correct positioning, the opening of the distal flange in the cavity and slow withdrawal of the entire delivery system until the distal flange was in contact with the wall was controlled by EUS while the opening of the proximal flange was then observed endoscopically.

The EUS visibility of each step involved in the transmural stent insertion was assessed by the operators as “visible” or “not visible”: (1) Access to the cyst by needle or cystotome; (2) insertion of a guide wire; (3) introducing of the diathermy and delivery system; (4) opening of the distal flange; and (5) slow withdrawal until contact of distal flange to cavity wall.

Final correct position of the FCSEMS was confirmed endoscopically when the liquid content of the WOPN emptied through the stent into the gastric lumen. Fluoroscopy was not used at any time during the procedure.

As clinically indicated, endoscopic necrosectomy was performed through the large diameter metal stent[10]. When the collection had shrunk to less than 4 cm on ultrasound or computed tomography after at least 6 wk follow-up the metal stent was endoscopically removed. Additional pigtail plastic stents were not inserted during this study, neither through the FCSEMS to prevent stent migration nor after removal of the FCSEMS.

Further imaging after stent removal was reviewed to assess recurrence of pancreatic collections.

Primary outcome of this study was the technical feasibility of EUS-guided FCSEMS placement without fluoroscopy and the EUS visibility of the different steps during stent insertion. Technical success was defined as correct positioning of the transmural FCEMS without using fluoroscopy during the procedure. Secondary outcome parameters included adverse events and clinical outcome.

Continuous variables were reported in median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were described as frequencies. The technical success of EUS-guided stent insertion was reported according to intention-to-treat-analysis. Procedure-related adverse events are given as per-protocol.

From the prospective database, 27 consecutive patients with symptomatic walled-off necrosis after necrotizing pancreatitis were identified who were referred for EUS-guided insertion of FCSEMS to drain the fluid content and necrotic debris. Patient demographics and indications for endoscopic intervention are given in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Sex, male/female | 21/6 |

| Median age (interquartile range), yr | 54 (45-63) |

| Median size of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (interquartile range), cm | 14 (12-16) |

| Cause of pancreatitis | |

| Alcohol induced | 9 |

| Biliary | 17 |

| Idiopathic | 1 |

| Main indication | |

| Gastric outlet obstruction | 15 |

| Biliary obstruction | 3 |

| Infection/fever despite antibiotic therapy | 9 |

In 2 patients large diameter traversing arteries within the cavity were detected by Doppler during the orientating EUS, therefore the insertion of FCSEMS was not attempted to avoid possible erosion of the vessels by the stent edges with reducing collection size. In one patient a plastic stent was inserted instead, the other suffered a spontaneous haemorrhage into the necrotic cavity a week later and was found to have a necrotic tumour at surgery.

In all other patients, the EUS-guided insertion of the FCSEMS was technically successful achieving correct stent positioning without any fluoroscopy (92.6%) (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Patients, n = 27 |

| Technical success | 25 (92.6%) |

| Type of stent | |

| AxiosTM | 8 |

| NAGITM | 17 |

| Stent diameter, mm | |

| 12 | 2 |

| 14 | 11 |

| 15 | 10 |

| 16 | 2 |

| Transduodenal/transgastric/transoesophageal approach | 1/24/0 |

| Adverse events | 4 (in 3 patients) |

| Stent migration | 1 (after WOPN resolved) |

| Self-limiting bleeding | 1 |

| Perforation/Pneumoperitoneum | 0 |

| Readmission with fever | 2 |

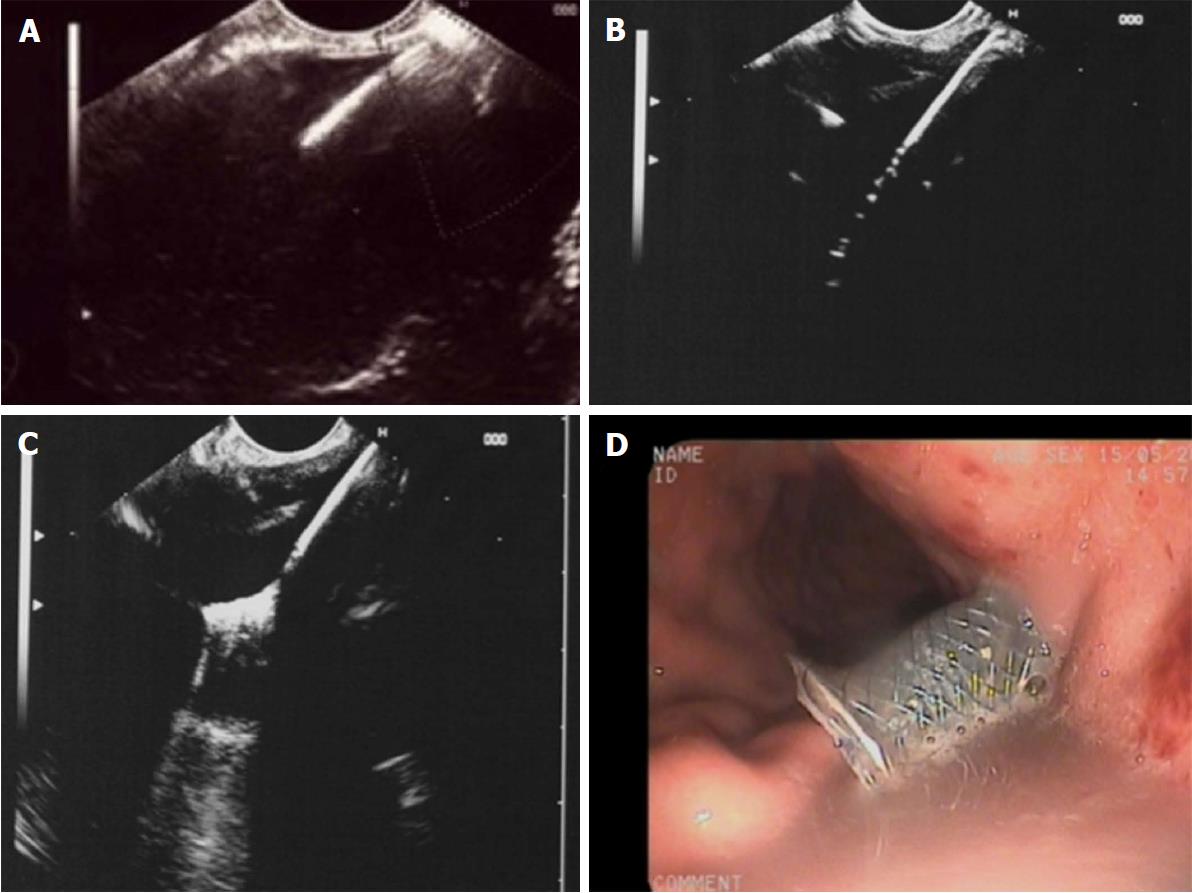

(1) Access to the cyst by needle or cystotome could be endosonographically visualized in all 25 patients; (2) insertion of a guide wire could be monitored on EUS in all patients, however, the visibility of the entire coiling of the wire was limited in 6 patients with large amounts of debris within the cavity (> 30%); (3) introduction of the diathermy and delivery system was clearly seen, both in all NAGITM as well as all Hot AxiosTM stents. The diathermy produces artefacts on EUS during transmural transition but the caliber difference between guidewire and diathermy/delivery system is clearly visible within the fluid filled cavity; (4) opening of the distal flange could be clearly observed using all stents; and (5) the slow withdrawal of the opened distal flange until reaching contact to the cavity wall could be continuously monitored with both stent types in all patients (Figure 1).

In nine patients, endoscopic necrosectomy through the large diameter metal stent became necessary due to incomplete clearance of debris or stent occlusion by obstructing necrotic tissue and/or infection.

Overall procedure-related adverse events occurred in 3 of 25 patients (12.0%); one patient developed self-limiting bleeding, two patients were readmitted with fever and a blocked stent and subsequently underwent endoscopic necrosectomy. In one of the readmitted patients the stent migrated spontaneously after 4 wk but the WOPN had already resolved. There was no procedure-related mortality (Table 2).

After 8 wk the WOPN had resolved in all but one patient (96.0%) to a diameter of less than 4 cm. The patient with persistent WOPN had deep extensions of the inflammatory cavity into the retrocolic gutter requiring additional percutaneous drainage.

There were no adverse events at the time of stent removal. From the 24 patients with successful resolution of the WOPN, 20 had further imaging (ultrasound, CT or MRCP) after six months. None had reoccurrence of pancreatic collections indicating disconnected pancreatic tail syndrome. Four patients did not have follow-up of more than 8 wk available as they had been discharged back to the referring hospitals.

The endoscopic management of WOPN has been simplified by technical advances in EUS and the development of specially designed, dumbbell-shaped, fully covered large caliber stents which can be placed endoscopically in a few or even only one step[5,11-13]. In contrast to plastic stents, the radial expansive forces of FCSEMS and the lumen-apposing design avoid leakage of fluid along the newly created transmural tract. The wide flanges should prevent dislodgment and migration.

Usually, FCSEMS are placed under EUS-guidance with fluoroscopic control of guidewire insertion, tract enlargement and stent deployment. In these series, we could show that all the steps required for endoscopic transmural insertion of FCSEMS into a WOPN can be visualized and safely monitored by EUS without the need for fluoroscopy. Although we used different stents due to availability and preference in the different centres, the EUS visibility of both types during all steps of the procedure was excellent: The cystotome access, the insertion of the guidewire, the transmural advancing of the diathermy and delivery system, the opening of the distal flange and the correct positioning by withdrawal to the wall of the WOPN could be controlled and displayed by EUS in all patients.

On the other hand, the endosonographic visibility of access needle, guide-wire, cystotome and stent delivery system might depend on the debris content within the WOPN. None of the WOPNs in this series had debris of more than 50% but we only very rarely see WOPN with debris filling more than 50% of the cavity.

Fluoroscopy has not been applied in any of the transgastric stent insertions in this study. It might be argued that the availability of fluoroscopy is important should adverse events occur during the procedure. However, the most common complications related to EUS-guided transluminal stent insertion into pancreatic collections can be managed endoscopically or recognized endosonographically as well. In case of massive bleeding it might be helpful to inflate a balloon within the stent to achieve tamponade. Stent dislocation or incorrect positioning is recognized endoscopically and usually requires repeating the procedure.

Recently, an intra-channel release technique has been described for the hot axios stent which also enables a fluoroless placement[14]. However, it remains unclear whether fluoroscopy has been used additionally in these cases and the visibility of the deployment steps has not been reported. Another retrospective recent study reports on 25 selected patients in whom EUS-guided stent insertion was safely performed without fluoroscopy[15].

The strength of our study is the fact that we included consecutive patients and systematically assessed the visibility of all procedure steps. Another advantage is that we tested the EUS-visibility of two types of stents, a lumen apposing and another FCSEMs, the most commonly inserted metal stents for the purpose of WOPN drainage.

In nine patients endoscopic necrosectomy to extract obstructing necrotic material from the stent was required. The large diameter of the stents allows the direct endoscopic access and the anchoring flanges prevent stent dislodgment during the endoscopic debridement of the necrotic cavity.

For 20 patients imaging follow-up after 6 mo was available. None of these patients had signs of re-occurrence of a peripancreatic collection after removal of the FCSEMS as would be expected in case of disconnected pancreatic tail syndrome. The large diameter of the newly created track between pancreatic cavity and gastric lumen by the FCSEMS might facilitate persistence of a pancreaticogastric fistula if the pancreatic tail cannot drain via the papilla.

Our study has some limitations. The endoscopists evaluated the visibility of the different procedure steps themselves during the intervention. The procedures were not recorded and images were not evaluated by a second person. Also, we are tertiary centers practicing advanced endoscopic ultrasound procedures and our results may not be replicated in other centers. However, we believe that patients with complex WOPN should be treated in expert centers with multidisciplinary teams and expertise in pancreatic surgery. In addition, our study was not randomized or controlled and the sample size was relatively small. Ideally, a larger randomized study with a control arm using EUS and fluoroscopic imaging should be conducted.

In conclusion, all procedural steps during EUS-guided insertion of FCSEMS are well visualized by EUS. Non-fluoroscopic EUS-guided transmural insertion of FCSEMS for drainage of WOPN is feasible and appears to be safe and effective. Without the need for fluoroscopy and radiation exposure, EUS-guided drainage of WOPN with insertion of FCSEMS can become a bedside intervention for critically ill patients.

Transluminal placement of specially designed fully covered self-expandable and lumen-apposing metal stents (FCSEMS) has improved the management and clinical outcome of walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN). Most often this procedure is performed under fluoroscopy after EUS-guided access.

Without the need for fluoroscopy EUS-guided drainage using large diameter metal stents would also become available in endoscopy units and at the bedside of critically ill patients. This procedure is often crucial for the management of patients with complex pancreatic necrosis.

The principal aim of this study is to assess the feasibility and safety of fluoroless, purely EUS-guided insertion of self-expandable and lumen-apposing stents for the drainage of walled-off pancreatic necrosis.

In 27 consecutive patients, we investigated the EUS-visibility of all procedural steps required to insert a fully covered self-expandable metal stent as transluminal drainage of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. EUS-visibility, technical success, outcome and adverse events were analysed.

All procedural steps could be visualised by EUS alone. Fluoroscopy was avoided in all patients undergoing transmural stent placement. EUS-guided insertion of the FCSEMS was technically successful achieving correct stent positioning in 92.6%.

Non-fluoroscopic EUS-guided transmural insertion of FCSEMS for drainage of WOPN is feasible and appears to be safe and effective.

Large multi-center studies and prospective registries would provide more information on the use of EUS-guided WOPN drainage as bedside intervention, its safety and long-term outcome, the best time intervals when to remove the metal stents.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fujino Y, Ker CG, Kin T, Kozarek RA, Nakano H, Sperti C S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, Geskus RB, Besselink MG, Bollen TL, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Hazebroek EJ, Nijmeijer RM. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 38.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van Brunschot S, Fockens P, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Voermans RP, Poley JW, Gooszen HG, Bruno M, van Santvoort HC. Endoscopic transluminal necrosectomy in necrotising pancreatitis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1425-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, Yates MR. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:7-17. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Baron TH, Pérez-Miranda M, Sánchez-Yagüe A, Gornals J, Gonzalez-Huix F, de la Serna C, Gonzalez Martin JA, Gimeno-Garcia AZ, Marra-Lopez C. Evaluation of the short- and long-term effectiveness and safety of fully covered self-expandable metal stents for drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: results of a Spanish nationwide registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:450-457.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Siddiqui AA, Adler DG, Nieto J, Shah JN, Binmoeller KF, Kane S, Yan L, Laique SN, Kowalski T, Loren DE. EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections and necrosis by using a novel lumen-apposing stent: a large retrospective, multicenter U.S. experience (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:699-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Shah RJ, Shah JN, Waxman I, Kowalski TE, Sanchez-Yague A, Nieto J, Brauer BC, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with lumen-apposing covered self-expanding metal stents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:747-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Braden B, Dietrich CF. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis: new technical developments. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16191-16196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rana SS, Bhasin DK, Rao C, Gupta R, Singh K. Non-fluoroscopic endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural drainage of symptomatic non-bulging walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS, Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis-2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. 2013;102-111. |

| 10. | Seifert H, Wehrmann T, Schmitt T, Zeuzem S, Caspary WF. Retroperitoneal endoscopic debridement for infected peripancreatic necrosis. Lancet. 2000;356:653-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Walter D, Will U, Sanchez-Yague A, Brenke D, Hampe J, Wollny H, López-Jamar JM, Jechart G, Vilmann P, Gornals JB. A novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: a prospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Binmoeller KF, Shah J. A novel lumen-apposing stent for transluminal drainage of nonadherent extraintestinal fluid collections. Endoscopy. 2011;43:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Itoi T, Binmoeller KF, Shah J, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:870-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anderloni A, Attili F, Carrara S, Galasso D, Di Leo M, Costamagna G, Repici A, Kunda R, Larghi A. Intra-channel stent release technique for fluoroless endoscopic ultrasound-guided lumen-apposing metal stent placement: changing the paradigm. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E25-E29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yoo J, Yan L, Hasan R, Somalya S, Nieto J, Siddiqui AA. Feasibility, safety, and outcomes of a single-step endoscopic ultrasonography-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections without fluoroscopy using a novel electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing, self-expanding metal stent. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:131-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |