Published online Apr 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i4.74

Peer-review started: December 4, 2017

First decision: December 22, 2017

Revised: January 18, 2018

Accepted: March 14, 2018

Article in press: March 15, 2018

Published online: April 16, 2018

Processing time: 133 Days and 16.3 Hours

To evaluate the impact of the timing of capsule endoscopy (CE) in overt-obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB).

Retrospective, single-center study, including patients submitted to CE in the setting of overt-OGIB between January 2005 and August 2017. Patients were divided into 3 groups according to the timing of CE (≤ 48 h; 48 h-14 d; ≥ 14 d). The diagnostic and therapeutic yield (DY and TY), the rebleeding rate and the time to rebleed were calculated and compared between groups. The outcomes of patients in whom CE was performed before (≤ 48 h) and after 48 h (> 48 h), and before (< 14 d) and after 14 d (≥ 14 d), were also compared.

One hundred and fifteen patients underwent CE for overt-OGIB. The DY was 80%, TY-46.1% and rebleeding rate - 32.2%. At 1 year 17.8% of the patients had rebled. 33.9% of the patients performed CE in the first 48 h, 30.4% between 48h-14d and 35.7% after 14 d. The DY was similar between the 3 groups (P = 0.37). In the ≤ 48 h group, the TY was the highest (66.7% vs 40% vs 31.7%, P = 0.005) and the rebleeding rate was the lowest (15.4% vs 34.3% vs 46.3% P = 0.007). The time to rebleed was longer in the ≤ 48 h group when compared to the > 48 h groups (P = 0.03).

Performing CE within 48 h from overt-OGIB is associated to a higher TY and a lower rebleeding rate and longer time to rebleed.

Core tip: An early diagnosis with capsule endoscopy (CE) in overt-obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) patients can lead to an appropriate specific intervention, better long term-outcomes and reduce unnecessary medical costs. In this paper we evaluated the impact of the timing of CE in these patients. ESGE recommends performing CE as soon as possible after the bleeding episode, optimally within 14 d. We found that in spite of a similar diagnostic yield, performing CE within 48 h is associated with greater therapeutic yield, less rebleeding episodes, and a longer rebleeding-free time. This suggests that a more timely approach in the evaluation of overt-OGIB than the 14 d recommendation is advisable.

- Citation: Gomes C, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Ponte A, Silva J, Rodrigues JP, Sousa M, Silva JC, Carvalho J. Impact of the timing of capsule endoscopy in overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding on yield and rebleeding rate - is sooner than 14 d advisable? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(4): 74-82

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i4/74.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i4.74

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is defined as recurrent acute or chronic bleeding of unknown origin that persists or recurs despite negative findings from bidirectional endoscopy[1]. OGIB accounts for approximately 5% of all cases of gastrointestinal bleeding and is usually due to a lesion in the small bowel (SB)[2]. OGIB can be classified as overt or occult. Overt-OGIB refers to recurrent or persistent visible bleeding (hematochezia, melena or hematemesis) and occult-OGIB is defined as recurrent or persistent iron-deficiency anemia and/or positive fecal occult blood[1].

Since the introduction of Capsule Endoscopy (CE) in 2000[3], SB visualization became possible with this safe and non-invasive method. Its advent has resulted in a paradigm shift in the management of patients with OGIB[1]. OGIB is the main indication for both the performance of CE and device-assisted enteroscopy[2,4]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends CE as the first-line investigation in patients with OGIB, and in overt presentations, their recommendation is to perform CE as soon as possible after the bleeding episode, optimally within 14 d[2]. CE has been shown to have a high diagnostic yield (DY) in OGIB and is significantly more sensitive when compared to other alternative diagnostic radiographic and endoscopic methods[5-7].

Patients with overt-OGIB are more likely to present a significant lesion, which is associated with recurrent bleeding[8-11]. An early definitive diagnosis in these patients can lead to an appropriate specific intervention, better outcomes and reduce unnecessary medical costs[11,12].

Using CE early in the course of overt-OGIB seems to be attractive, because of the higher DY, and even if no lesion is found, at least, it has the potential to localize the source of the bleeding[12-15]. However, the data is limited and the optimal timing for CE in overt-OGIB remains unclear[1,16].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of the timing of CE in overt-OGIB in the DY, therapeutic yield (TY), rebleeding rate and time to rebleed, mainly when CE is performed within the first 48 h.

A cohort of patients with overt-OGIB who underwent CE after bidirectional endoscopy at Centro Hospital Vila Nova de Gaia from January 2005 to August 2017 was evaluated. Patients were follow-up until October 2017.

Patient clinical information was retrospectively collected from electronic medical records, including demographic characteristics (gender, age); comorbidities (cardiovascular, renal, hepatic disease, tumor, previous abdominal surgeries); medical therapy [anticoagulants, antiplatelet and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s)]; hemoglobin (Hg) at admission, international normalized ratio (INR) at admission, and number of units of packed red blood cells (RBC) transfused prior to CE.

The Given® Video Capsule and Mirocam® Video Capsule systems were used in this study. CE studies were carried out according to our unit’s protocol, which includes an overnight fast without prior bowel preparation, suspension of iron supplements 8 d before the procedure and a liquid diet in the last dinner. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients were allowed to have an oral light diet 4 h after CE ingestion. Patients in whom CE was Mirocam®, were evaluated 1 h and 2 h after CE ingestion. Removal of the recorder 12 h after CE ingestion or earlier if real-time viewing confirms that the device has already reached the colon. A prokinetic agent (metoclopramide 10 mg) was administered when the capsule was found in the stomach.

Overt-OGIB (melena or hematochezia) was subdivided into ongoing-overt-OGIB (bleeding during the procedure, at the time of CE) and previous-overt-OGIB (bleeding in the past but not during the procedure).

The period between overt-OGIB and CE was divided into 3 groups: Within 48 h (≤ 48 h); between 48 h and 14 d (48 h-14 d); and after 14 d (≥ 14 d). The outcomes of patients whose CE was performed before (≤ 48 h) and after 48 h (> 48 h), and before (< 14 d) and after 14 d (≥ 14 d), were also compared.

CE cleansing was evaluated according to the scale Brotz et al [17-18]. Cleansing was considered appropriate when graduated as excellent, good or fair.

CE findings were classified as positive and negative findings. Positive findings included bleeding without visible lesions, angiodysplasia, varices, hemangioma, ulcer, erosion, eroded polyps, diverticulum with bleeding stigmata, small-bowel tumor, or extra-small-bowel causes that could explain the bleeding (extra-SB cause of bleeding). Bleeding was subdivided into recent or active. The diagnostic yield was defined as the proportion of CE with positive findings to the total number of CE.

Treatment for OGIB was divided into medical, endoscopic, radiological or surgical. The therapeutic yield was defined as the proportion of patients performing one of the above mentioned treatments to the total number of patients.

The occurrence and time to rebleeding episodes, as well as the mortality, were also evaluated. Rebleeding episodes were defined as evidence of melena or hematochezia, a drop in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL or more from baseline, or the need for transfusion[19-21].

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 23.0. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the patient’s demographic features, clinical characteristics and type of endoscopic findings. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and numeric variables as means. Results are expressed as percentages or means ± SD for continuous variables.

The χ2 test was used to compare non-continuous variables. The t-test and ANOVA test were used to compare continuous variables. The Kaplan-Meier test was used to calculate the time to rebleed. The Log-Rank test was used to compare the time to rebleed between groups. A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

A total of 115 patients underwent CE for overt-OGIB. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 65.1 years (SD ± 14.6) and 51.3% percent (n = 59) were female. The mean delay between overt-OGIB and CE was 48.9 d (SD ± 161.5).

| No. of patients (n = 115) | All | ≤ 48 h(n = 39, 33.9) | 48 h-14 d(n = 35, 30.4) | ≥ 14 d(n = 41, 35.7) | P value1 |

| Time to CE after OOGIB, mean ± SD, d | 48.9 ± 161.5 | ||||

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 65.1 ± 14.6 | 63 ± 14.2 | 63.9 ± 15.9 | 68.2 ± 13.6 | 0.234 |

| Female sex | 59 (51.3) | 18 (46.2) | 20 (57.1) | 21 (51.2) | 0.64 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 61 (53) | 20 (51.3) | 16 (45.7) | 25 (61) | 0.40 |

| Renal disease | 20 (17.4) | 2 (5.1) | 8 (22.9) | 10 (24.4) | 0.045 |

| Hepatic disease | 8 (7) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (7.3) | 0.940 |

| Tumour | 7 (6.1) | 2 (5.1) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (7.3) | 0.91 |

| Previous abdominal surgeries | 27 (23.5) | 10 (25.6) | 8 (22.9) | 9 (22) | 0.92 |

| Drugs | |||||

| Anti-platelet drugs | 49 (42.6) | 17 (43.6) | 13 (37.1) | 19 (46.3) | 0.71 |

| Anticoagulation | 25 (21.7) | 8 (20.5) | 9 (25.7) | 8 (19.5) | 0.79 |

| NSAIDs | 10 (8.7) | 4 (10.3) | 2 (5.7) | 4 (9.8) | 0.75 |

| Melena | 63 (54.8) | 18 (46.2) | 21 (60) | 24 (58.5) | 0.41 |

| Hematochezia | 52 (45.2) | 21 (53.8) | 14 (40) | 17 (41.5) | 0.41 |

| On-going OOGIB | 62 (53.9) | 39 (100) | 17 (48.6) | 6 (14.6) | < 0.001 |

| Hg at admission, mean ± SD, g/dL | 8.91 ± 6.24 | 8.51 ± 2.65 | 8.26 ± 2.32 | 9.93 ± 9.88 | 0.12 |

| INR at admission, mean ± SD | 1.61 ± 1.18 | 1.57 ± 1.00 | 1.83 ± 1.65 | 1.47 ± 0.77 | 0.08 |

| Packed RBC transfusions, mean ± SD, units | 1.41 ± 1.31 | 1.41 ± 1.37 | 1.51 ± 1.20 | 1.29 ± 1.36 | 0.29 |

| Inpatient | 78 (67.8) | 39 (100) | 31 (88.6) | 8 (19.5) | < 0.001 |

Most patients were referred for melena (54.8%, n = 63), while 45.2% (n = 52) were referred for hematochezia. On-going-overt-OGIB was present in 53.9 % (n = 62). In 67.8% of the patients, CE was performed during hospitalization. The two systems of capsule endoscopy (Given® and Mirocam®) were compared. Only the presence of on-going OGIB and the CE performance in the inpatient setting were significant higher with the Mirocam® system (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| No. of patients (n = 115) | All | Given® (n = 32, 27.8) | Mirocam® (n = 83, 72.2) | P value1 |

| Time to CE after OOGIB, mean ± SD, d | 48.9 ± 161.5 | 51 ± 119.1 | 48.1 ± 175.8 | 0.93 |

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 65.1 ± 14.6 | 60.8 ± 16.9 | 66.8 ± 13.3 | 0.08 |

| Female sex | 59 (51.3) | 18 (56.2) | 41 (49.4) | 0.51 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 61 (53) | 15 (46.9) | 46 (55.4) | 0.41 |

| Renal disease | 20 (17.4) | 3 (9) | 17 (20.5) | 0.16 |

| Hepatic disease | 8 (7) | 2 (6) | 6 (7) | 0.85 |

| Tumour | 7 (6.1) | 1 (3) | 6 (7) | 0.41 |

| Previous abdominal surgeries | 27 (23.5) | 5 (16) | 22 (26.5) | 0.22 |

| Drugs | ||||

| Anti-platelet drugs | 49 (42.6) | 12 (37.5) | 37 (44.6) | 0.49 |

| Anticoagulation | 25 (21.7) | 7 (21.9) | 18 (21.7) | 0.98 |

| NSAIDs | 10 (8.7) | 4 (12.5) | 6 (7) | 0.37 |

| Melena | 63 (54.8) | 21 (65.6) | 42 (50.6) | 0.15 |

| Hematochezia | 52 (45.2) | 11 (34.4) | 41 (49.4) | 0.15 |

| On-going OOGIB | 62 (53.9) | 7 (21.9) | 55 (66.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hg at admission, mean ± SD, g/dL | 8.91 ± 6.24 | 8.94 ± 2.77 | 8.94 ± 7.14 | 0.99 |

| INR at admission, mean ± SD | 1.61 ± 1.18 | 1.55 ± 0.81 | 1.64 ± 1.29 | 0.72 |

| Packed RBC transfusions, mean ± SD, units | 1.41 ± 1.31 | 1.28 ± 1.42 | 1.45 ± 1.27 | 0.55 |

| Inpatient | 78 (67.8) | 18 (56.2) | 60 (72.3) | 0.01 |

| Timing of CE | ||||

| ≤ 48 h | 39 (33.9) | 4 (12.5) | 35 (42.2) | 0.009 |

| 48 h-14 d | 35 (30.4) | 14 (43.75) | 21 (25.3) | |

| ≥ 14 d | 41 (35.7) | 14 (43.75) | 27 (32.5) |

CE findings are presented in Table 3. The CE reached the cecum in 90.4% of all examinations (n = 104) and in 75.7% the cleansing was considered appropriate (n = 87). Almost all patients had positive findings (81.8%, n = 94). The most frequent findings were vascular lesions-29.6% (angiodysplasia 26.1%, varices 0.9% and hemangioma 2.6%); ulcers/erosions-16.4% (10.4%/6%); diverticula 1.7% and mass lesions-13.1%: tumors 9.6% (adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumours, GIST, carcinoid tumours and subepitelial lesions) and polyps 3.5%. Blood in the GI tract was observed in 41.7% of the patients, and was divided into active (73%) and inactive bleeding (27%).

| All (n = 115) | ≤ 48 h (n = 39) | 48 h-14 d (n = 35) | ≥ 14 d (n = 41) | P value1 | |

| Total enteroscopy | 104 (90.4) | 33 (84.6) | 32 (91.4) | 39 (95.1) | 0.27 |

| Appropriate cleansing | 87 (75.7) | 21 (53.8) | 31 (88.6) | 35 (85.4) | 0.00 |

| Positive Findings | 94 (81.8) | 33 (84.3) | 31 (88.6) | 31 (75.6) | 0.30 |

| Angiodysplasia | 30 (26.1) | 6 (15.4) | 11 (31.4) | 13 (31.7) | |

| Varices | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0 | |

| Hemangioma | 3 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Ulcers | 12 (10.4) | 3 (7.7) | 5 (14.3) | 4 (9,8) | |

| Erosions | 7 (6) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.9) | 5 (12.2) | |

| Tumours | 11 (9.6) | 2 (5.1) | 7 (20) | 2 (4.9) | |

| Polyps | 4 (3.5) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Diverticula | 2 (1.7) | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 1 (2.4) | |

| Extra-SB cause | 2 (1.7) | 2 (5.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Bleeding | 48 (41.7) | 23 (59) | 15 (42.9) | 10 (24.4) | 0.007 |

| Inactive bleeding | 13 (11.3) | 6 (15.4) | 5 (14.3) | 2 (4.9) | 0.27 |

| Active bleeding | 35 (30.4) | 17 (43.6) | 10 (28.6) | 8 (19.5) | 0.06 |

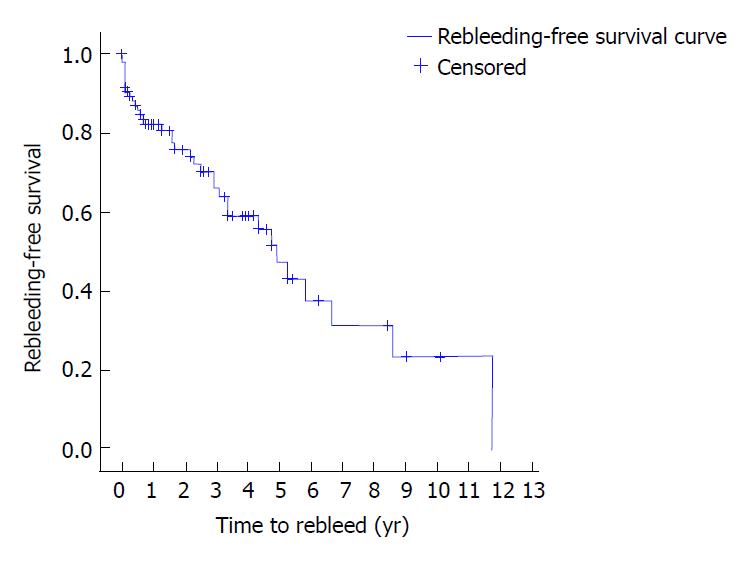

The DY was 80% (n = 92), TY 46.1% (n = 53), rebleeding rate 32.2% (n = 37), and the global mortality 24.3% (n = 28) (Table 4). At 1 year the rebleeding rate was 17.8%, at 2 years 24.1%, at 3 years 33.9%, at 4 years 30.8% and at 5 years 52.6% (Table 4 and Figure 1).

| Outcome | All (n = 115) | ≤ 48 h (n = 39) | 48 h-14 d (n = 35) | ≥ 14 d (n = 41) | P value1 | P1 (≤ 48 h vs 48 h-14 d) |

| DY | 92 (80) | 32 (82.1) | 30 (85.7) | 30 (73.2) | 0.37 | 0.67 |

| TY | 53 (46.1) | 26 (66.7) | 14 (40) | 13 (31.7) | 0.005 | 0.02 |

| RR | 37 (32.2) | 6 (15.4) | 12 (34.3) | 19 (46.3) | 0.007 | 0.06 |

| Time to rebleed, yr | 1 yr, 17.8 | 1 yr, 11.8 | 1 yr, 20.1 | 1 yr, 21.9 | ||

| 2 yr, 24.1 | 2 yr, 11.8 | 2 yr, 30.7 | 2 yr, 31.4 | |||

| 3 yr, 33.9 | 3 yr, 18.5 | 3 yr, 37 | 3 yr, 46.9 | |||

| 4 yr, 30.8 | 4 yr, 18.5 | 4 yr, 44 | 4 yr, 58.2 | |||

| 5 yr, 52.6 | 5 yr, 60 | 5 yr, 53.4 | 5 yr, 64.2 | |||

| Mortality | 28 (24.3) | 9 (23.1) | 10 (28.6) | 9 (22) | 0.78 | 0.59 |

The treatment was conservative in 53.9% of the patients (n = 62), endoscopic in 26.1% (n = 30), surgical in 16.5% (n = 19), radiological in 2.6% (n = 3) and one of the patients performed endoscopic therapy (APC for the treatment of angiodysplasia) and was subsequently submitted to surgical treatment of a GIST (gastrointestinal stromal tumor) (found in the same enteroscopy) (0.9%) (Table 5).

| Type of treatment | All (n = 115) | ≤ 48 h (n = 39) | 48 h-14 d (n = 35) | ≥ 14 d (n = 41) | P value1 |

| Conservative | 62 (53.9) | 13 (33.3) | 21 (60) | 28 (68.3) | 0.005 |

| Endoscopic | 30 (26.1) | 14 (35.9) | 6 (17.1) | 10 (24.4) | 0.18 |

| Surgical | 19 (16.5) | 9 (23.1) | 7 (20) | 3 (7.3) | 0.13 |

| Radiological | 3 (2.6) | 2 (5.1) | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 0.353 |

| Endoscopic + Surgical | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0.37 |

≤ 48 h vs 48 h-14 d vs ≥ 14 d: Capsule endoscopy was performed in the first 48 h in 33.9% of the patients (n = 39), between 48 h-14 d in 30.4% (n = 35) and after 14 d in 35.7% (n = 41) (Table 1).

The mean age was not significantly different between groups (P = 0.23). Regarding the baseline characteristics and comorbidity status, only the presence of renal disease was more prevalent in the ≥ 14 d group (P = 0.04) (Table 1).

On-going overt-OGIB was present in all patients in the ≤ 48 h group, and all of them were still hospitalized when CE was performed (Table 1). These data were significantly different from the other groups (100% vs 48.6% vs 14.6%, P < 0.001 and 100% vs 88.6% vs 19.5%, P < 0.001, respectively).

The Mirocam® system was performed more often in the first 48 h (P < 0.05), compared to the Given® system (42.2% vs 12.5%, P = 0.009) (Table 2).

The total of positive findings in CE did not appear to differ between groups (P = 0.3), however active bleeding tends to be more prevalent in the ≤ 48 h group (43.6% vs 28.6% vs 19.5%, P = 0.06) (Table 3).

The DY and mortality rate were similar between the 3 groups (P = 0.37 and P = 0.78, respectively). Conversely, the TY was significantly higher (66.7% vs 40% vs 31.7%, P = 0.005) and the rebleeding rate lower (15.4% vs 34.3% vs 46.3% P = 0.007) in the ≤ 48 h group (Table 4). Conservative treatment was the only type of treatment that differed between groups, being higher when CE was performed after 14 d (33.3% vs 60% vs 68.3%, P = 0.005) (Table 5).

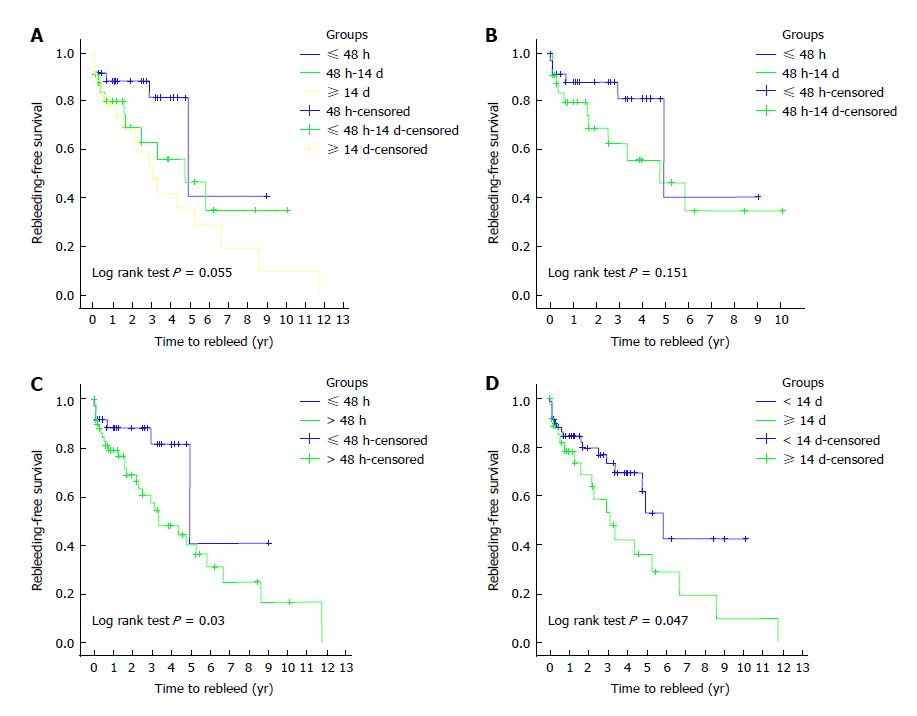

Time to rebleed was not significantly different between groups (P = 0.055) (Figure 2A).

≤ 48 h vs 48 h-14 d: In spite of a similar DY and mortality rate (P = 0.67 and 0.59, respectively), the TY was significantly higher (66.7% vs 40%, P = 0.02) and the rebleeding rate tended to be inferior (15.4% vs 34.3%, P = 0.06) in the ≤ 48 h group. The time to rebleed was not significantly different (P = 0.15) (Table 4 and Figure 2B).

≤ 48 h vs > 48 h: The DY and mortality were similar between the 2 groups (P = 0.69 and P = 0.82, respectively). However, the TY was higher (66.7% vs 35.5%, P = 0.002) and rebleeding episodes were less frequent (15.4% vs 43%, P = 0.004) in the ≤ 48 h group. The time to rebleed was also significantly longer (P = 0.03) (Figure 2C and Table 6).

| Outcome | ≤ 48 h | > 48 h | P1 (≤ 48 h vs > 48h) | < 14 d | ≥ 14 d | P1 (< 14 d vs ≥ 14 d) |

| DY | 32 (82.1) | 60 (78.9) | 0.69 | 62 (83.8) | 30 (73.2) | 0.17 |

| TY | 26 (66.7) | 27 (35.5) | 0.002 | 40 (54.1) | 13 (31.7) | 0.02 |

| RR | 6 (15.4) | 31 (43) | 0.004 | 18 (25) | 19 (46.3) | 0.008 |

| Time to re-bleed, yr | 1 yr, 11.8 | 1 yr, 1 | 1 yr, 15.6 | 1 yr, 21.9 | ||

| 2 yr, 11.8 | 2 yr, 31.1 | 2 yr, 20.4 | 2 yr, 31.4 | |||

| 3 yr, 18.5 | 3 yr, 42.6 | 3 yr, 26.8 | 3 yr, 46.9 | |||

| 4 yr, 18.5 | 4 yr, 52 | 4 yr, 30.6 | 4 yr, 58.2 | |||

| 5 yr, 60 | 5 yr, 59.7 | 5 yr, 38.3 | 5 yr, 64.2 | |||

| Mortality | 9 (23.1) | 19 (25) | 0.82 | 19 (25.7) | 9 (22) | 0.66 |

< 14 d vs ≥ 14 d: The DY and mortality were also similar between these 2 groups (P = 0.17 and 0.66, respectively). However in the < 14 d group, the TY was higher and the rebleeding rate lower (54% vs 31.7%, P = 0.02; 25% vs 46.3%, P = 0.008, respectively). The time to rebleed was also significantly longer in the < 14 d group (P = 0.047) (Figure 2D and Table 6).

In our study, the timing of CE in the setting of overt-OGIB influenced several outcomes. The earlier performance of CE was associated with a higher TY, lower rebleeding rates and longer rebleeding-free time.

Some series reported that performing CE within 24-72 h from the onset of overt-OGIB, results in a DY higher than 60%[12,14,15]. Lecleire et al[14] analyzed the performance of emergency CE (within 24-48 h) in severe overt-OGIB and found that specific diagnostic and therapeutic procedures were undertaken in 78% of the patients. Apostolopoulos et al[12] enrolled patients with mild-to-moderate overt-OGIB that performed urgent CE (within 48 h) and reported a DY of 91.9%. So it seems that independently of the severity of bleeding, CE performed as soon as possible in overt-OGIB is associated with good outcomes.

On-going overt-OGIB has been associated with a higher number of positive CE findings in other studies[13,22-24]. In our study on-going overt-OGIB was present in the totality of patients in the ≤ 48 h group and declined progressively in the remaining groups.

Patient characteristics in both systems were analyzed. The presence of on-going OGIB and CE in the inpatient setting were significantly higher with the Mirocam® system (P < 0.05). When comparing the two systems according to the timing of CE performance, the Mirocam® system was more often used in the first 48 h, which can be associated to the presence of on-going bleeding. This can be explained by the fact that the Given® system was used in the beginning of the series and at that time there was not so much evidence about the use of urgent CE in the setting of a bleeding event.

When comparing different groups according to the timing of CE, previous studies have shown that the earlier the capsule study is started, the greater the DY achieved[13,16,25-30]. Several studies evaluating the timing from overt-OGIB to CE, such as 48-72 h[16,25,27], 1 wk[28], 10 d[29], 15 d[30] have already been reported, demonstrating that the DY was always superior whenever CE was performed earlier. In our study, that association was not found, since independently from the timing of CE, the DY was similar between all periods examined (P > 0.05). Then again, the ≤ 48 h group of CE had a tendency to detect active bleeding more often than the others groups (P = 0.06).

The main purpose of small bowel evaluation is to guide a subsequent therapeutic intervention, usually endoscopically[4,20,21,31]. In this sense, the TY is a better surrogate in the evaluation of the best timing of CE. In the present study, the TY was higher when CE was performed earlier, as it has been described in previous studies[13,16,26,27]. Yamada et al[26] found that the proportion of interventions were significantly higher in 1st and 2nd quartiles of time between CE and overt-OGIB (P = 0.048). Singh et al[27] enrolled patients with overt-OGIB in 2 groups (CE performed before and after 3 d), and found that the TY was higher in the first group (P = 0.046). More recently, Kim et al[16] showed that specific therapeutic interventions were performed in 26.7% of the patients in the ≤ 48 h group, a higher rate compared to the > 48 h group (P = 0.028). On the other hand, several studies demonstrate that the yield of therapeutic endoscopy in the setting of overt-OGIB is also higher the sooner it is performed[11].

The rebleeding rate was not systematically evaluated in other studies. In the study from Apostolopoulos et al[12] a rebleeding rate of 15.6% at 1 year was found in patients who performed CE in the first 48 h, a similar result to the 15.4% found in the present study in the same subset of patients (≤ 48 h). Furthermore, the present study demonstrated that this rebleeding rate was lower (P = 0.007) than the rebleeding rate of other patients subsets (48 h-14 d, > 14d).

The current recommendation of the ESGE guidelines on capsule endoscopy is to perform CE within 14 d from the bleeding event[2], but according to our study and to the studies described above, the therapeutic intervention is higher when CE is performed within 48 h.

Therefore, in the present study, the conservative approach was higher in the ≥ 14 d group and in this same group the rebleeding rate was also superior. This can be explained by the fact that when CE is done later in the course of the bleeding event, an effective therapeutic intervention to control bleeding is less often employed, which could lead to recurrent bleeding. The presence of renal disease was more prevalent in the ≥ 14 d group (P = 0.04), and usually this has been associated with greater risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, which could influence the outcomes[19,32].

When performance of CE before and after 48 h and before and after 14 d was compared, a shorter rebleeding-free time was found in groups > 48 h and ≥ 14 d (P = 0.03 and P = 0.047, respectively). Once again, these results suggest that performing CE as soon as possible can influence the long-term outcomes.

In conclusion, performing CE within 48 h from the onset of overt-OGIB is associated with a higher therapeutic yield, a lower rebleeding rate and a longer rebleeding-free time. These findings may prompt to a more timely approach in the evaluation of overt-OGIB than the current 14 d-time frame recommendation.

The present study has some limitations. First, it has a retrospective design with a small number of patients that has not the sufficient power to change the current recommendations. Therefore a prospective assessment of the timing of CE for this indication is warranted to confirm these findings. Second, the presence of renal disease was different between the groups, which can bias the results, mainly the rebleeding rate.

An early diagnosis with capsule endoscopy in overt-obscure gastrointestinal bleeding patients can lead to an appropriate specific intervention, better long term-outcomes and reduce unnecessary medical costs. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends performing capsule endoscopy as soon as possible after the bleeding episode, optimally within 14 d. In this paper we evaluated the impact of the timing of capsule endoscopy in these patients, focusing in an earlier evaluation.

As an earlier diagnosis could lead to an earlier and more effective therapy, the authors ought to evaluate the impact of an earlier capsule evaluation on the therapeutic yield and the rebleeding rate.

To evaluate how the timing of capsule endoscopy (CE) in overt-obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) could change management of overt-OGIB and future outcomes.

The diagnostic and therapeutic yield (DY and TY) rebleeding rate, time to rebleed and mortality were calculated and compared according to the timing of capsule endoscopy (≤ 48 h; 48 h-14 d and ≥ 14 d).

Despite a similar diagnostic yield, performing capsule endoscopy within 48 h is associated with greater therapeutic yield, less rebleeding episodes, and a longer rebleeding-free time. This suggests that a more timely approach than the 14 d recommendation in the evaluation of overt-OGIB should be considered.

Performing CE within 48 h from the onset of overt-OGIB is associated with a higher therapeutic yield, a lower rebleeding rate and a longer rebleeding-free time. It raises the question that performing CE sooner than 14 d could be advisable.

Our study has a retrospective design with a small number of patients, so a prospective assessment of this timing of CE in overt-OGIB in a larger population is warranted to confirm these findings and change recommendations.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chen CH, Goenka MK, Osawa S, Souza JLS S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Fisher L, Lee Krinsky M, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Friis C, Fukami N, Harrison ME, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue T, Khan K, Maple JT, Strohmeyer L, Sharaf R, Dominitz JA. The role of endoscopy in the management of obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:471-479. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Pennazio M, Spada C, Eliakim R, Keuchel M, May A, Mulder CJ, Rondonotti E, Adler SN, Albert J, Baltes P. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:352-376. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Pinho R, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, Mão-de-Ferro S, Ferreira S, Almeida N, Figueiredo P, Rodrigues A, Cardoso H, Marques M, Rosa B. Multicenter survey on the use of device-assisted enteroscopy in Portugal. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:264-274. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L. Meta-analysis: capsule enteroscopy vs. conventional modalities in diagnosis of small bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:595-604. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Pennazio M, Eisen G, Goldfarb N; ICCE. ICCE consensus for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1046-1050. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Hartmann D, Schmidt H, Bolz G, Schilling D, Kinzel F, Eickhoff A, Huschner W, Möller K, Jakobs R, Reitzig P. A prospective two-center study comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with intraoperative enteroscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:826-832. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dulai GS, Jensen DM. Severe gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2004;14:101-113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Lepileur L, Dray X, Antonietti M, Iwanicki-Caron I, Grigioni S, Chaput U, Di-Fiore A, Alhameedi R, Marteau P, Ducrotté P. Factors associated with diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding by video capsule enteroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1376-1380. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Pinto-Pais T, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Fernandes C, Ribeiro I, Fraga J, Carvalho J. Emergency single-balloon enteroscopy in overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: Efficacy and safety. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2:490-496. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Apostolopoulos P, Liatsos C, Gralnek IM, Kalantzis C, Giannakoulopoulou E, Alexandrakis G, Tsibouris P, Kalafatis E, Kalantzis N. Evaluation of capsule endoscopy in active, mild-to-moderate, overt, obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1174-1181. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lecleire S, Iwanicki-Caron I, Di-Fiore A, Elie C, Alhameedi R, Ramirez S, Hervé S, Ben-Soussan E, Ducrotté P, Antonietti M. Yield and impact of emergency capsule enteroscopy in severe obscure-overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2012;44:337-342. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Almeida N, Figueiredo P, Lopes S, Freire P, Lérias C, Gouveia H, Leitão MC. Urgent capsule endoscopy is useful in severe obscure-overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:87-92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Kim SH, Keum B, Chun HJ, Yoo IK, Lee JM, Lee JS, Nam SJ, Choi HS, Kim ES, Seo YS. Efficacy and implications of a 48-h cutoff for video capsule endoscopy application in overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E334-E338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Ponte A, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Carvalho J. Review of small-bowel cleansing scales in capsule endoscopy: A panoply of choices. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8:600-609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Brotz C, Nandi N, Conn M, Daskalakis C, DiMarino M, Infantolino A, Katz LC, Schroeder T, Kastenberg D. A validation study of 3 grading systems to evaluate small-bowel cleansing for wireless capsule endoscopy: a quantitative index, a qualitative evaluation, and an overall adequacy assessment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:262-270, 270.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Pinho R, Ponte A, Rodrigues A, Pinto-Pais T, Fernandes C, Ribeiro I, Silva J, Rodrigues J, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, Carvalho J. Long-term rebleeding risk following endoscopic therapy of small-bowel vascular lesions with device-assisted enteroscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:479-485. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Romagnuolo J, Brock AS, Ranney N. Is Endoscopic Therapy Effective for Angioectasia in Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:823-830. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Jackson CS, Gerson LB. Management of gastrointestinal angiodysplastic lesions (GIADs): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:474-483; quiz 484. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Iwamoto J, Mizokami Y, Shimokobe K, Yara S, Murakami M, Kido K, Ito M, Hirayama T, Saito Y, Honda A. The clinical outcome of capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:301-305. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK, Post JK, Fleischer DE. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Ribeiro I, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Marqués J, Fernandes C, Carvalho J. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: Which factors are associated with positive capsule endoscopy findings? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:334-339. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Goenka MK, Majumder S, Kumar S, Sethy PK, Goenka U. Single center experience of capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:774-778. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Yamada A, Watabe H, Kobayashi Y, Yamaji Y, Yoshida H, Koike K. Timing of capsule endoscopy influences the diagnosis and outcome in obscure-overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:676-679. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Singh A, Marshall C, Chaudhuri B, Okoli C, Foley A, Person SD, Bhattacharya K, Cave DR. Timing of video capsule endoscopy relative to overt obscure GI bleeding: implications from a retrospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:761-766. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Yada S, Yanaru-Fujisawa R, Kudo T, Yanai S, Nakamura S, Iida M. Factors associated with the clinical impact of capsule endoscopy in patients with overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2294-2301. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Katsinelos P, Chatzimavroudis G, Terzoudis S, Patsis I, Fasoulas K, Katsinelos T, Kokonis G, Zavos C, Vasiliadis T, Kountouras J. Diagnostic yield and clinical impact of capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding during routine clinical practice: a single-center experience. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:60-65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Bresci G, Parisi G, Bertoni M, Tumino E, Capria A. The role of video capsule endoscopy for evaluating obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: usefulness of early use. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:256-259. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Pinho R. The Vanishing Frontiers of Therapeutic Enteroscopy. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2015;22:133-134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Ishigami J, Grams ME, Naik RP, Coresh J, Matsushita K. Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk for Gastrointestinal Bleeding in the Community: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1735-1743. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |