Published online Oct 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i10.301

Peer-review started: April 30, 2018

First decision: June 6, 2018

Revised: July 6, 2018

Accepted: August 1, 2018

Article in press: August 1, 2018

Published online: October 16, 2018

Processing time: 83 Days and 3.5 Hours

To evaluate differences in capsule endoscopy (CE) performed in the setting of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) among premenopausal women (PMW) and menopausal women (MW).

Retrospective, single-center study, including female patients submitted to CE in the setting of OGIB between May 2011 and December 2016. Patients were divided into 2 groups according to age, considering fertile age as ≤ 55 years and postmenopausal age as > 55 years. The diagnostic yield (DY), the rebleeding rate and the time to rebleed were evaluated and compared between groups. Rebleeding was defined as a drop of Hb > 2 g/dL or need for transfusional support or presence of melena/hematochezia.

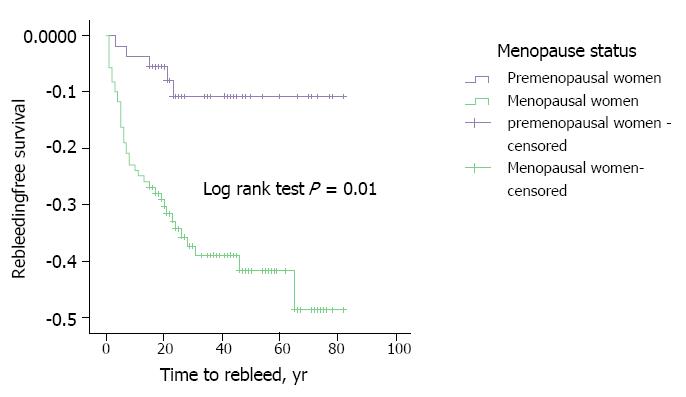

A hundred and eighty three female patients underwent CE for OGIB, of whom 30.6% (n = 56) were PMW and 69.4% (n = 127) were MW. The DY was 30.4% in PMW and 63.8% in MW. The most common findings were angiodysplasias in both groups (PMW: 21.4%, MW: 44.9%) (P = 0.003). In PMW, only 1.8% required therapeutic endoscopy. In 17.3% of MW, CE findings led to additional endoscopic treatment. Rebleeding at 1, 3 and 5 years in PMW was 3.6%, 10.2%, 10.2% and 22.0%, 32.3% and 34.2% in MW. Postmenopausal status was significantly associated with higher DY (P < 0.001), TY (P = 0.003), rebleeding (P = 0.031) and lower time to rebleed (P = 0.001).

PMW with suspected OGIB are less likely to have significant findings in CE. In MW DY, need for endoscopic treatment and rebleeding were significantly higher while time to rebleed was lower.

Core tip: Patients with negative findings in oesophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy with suspected obscure gastrointestinal-bleeding benefit from further capsule endoscopy (CE) study. Premenopausal women are frequently referred for CE. However in this subset of patients the pretest probability of positive findings is thought to be low. This paper compared the diagnostic yield (DY) as well as therapeutic yield (TY), rebleeding, hospitalization and mortality between premenopausal and menopausal women. We found that menopause status was significantly associated with positive findings, DY, TY, rebleeding and lower time to rebleed. This may lead to consider the exclusion of other comorbid pathologies in fertile age women before CE.

- Citation: Silva JC, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Ponte A, Rodrigues JP, Sousa M, Gomes C, Carvalho J. Yield of capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: A comparative study between premenopausal and menopausal women. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(10): 301-307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i10/301.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i10.301

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) accounts for approximately 5% of all cases of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and is usually due to a lesion in the small bowel[1]. OGIB can be classified as overt or occult[2]. In patients who have documented overt GI bleeding (excluding hematemesis) and negative findings on high-quality oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) and colonoscopy, capsule endoscopy (CE) is recommended as the next diagnostic step[3]. Patients with occult GI blood loss and negative findings in OGD and colonoscopy need comprehensive evaluation, including CE to identify an intestinal bleeding lesion[4]. In premenopausal women (PMW) gynecologic etiologies are the most frequent cause of anemia, although GI bleeding is reported as a cause of anemia in 12%-30%[5,6]. Re-bleeding after negative CE study in PMW is often due to menstrual blood loss[7-9]. Taking this in consideration it is necessary to clarify the differences in DY, TY and rebleeding in OGIB between PMW and MW. In PMW with suspected OGIB CE study may not be the first choice, considering the possibility of gynecologic blood loss and the lower rates of small bowel lesions[10].

Diagnostic yield (DY) of CE has already been evaluated, particularly in OGIB[11-13]. Age is an important factor, and more frequently older patients are referred for OGIB investigation through CE. In this group of patients DY is higher[14].

Few trials have compared CE findings in OGIB according to the menopausal status and some reported a lower DY in CE performed in PMW[10,15].

The present study aimed to evaluate and compare the DY of CE between PMW and menopausal women (MW). Secondary outcomes included a comparison of therapeutic yield (TY), rebleeding, hospitalization and mortality for OGIB between PMW and MW who underwent CE.

A cohort of female patients with OGIB who underwent CE after bidirectional endoscopy at Centro Hospital Vila Nova de Gaia from May 2011 to December 2016 was evaluated. Patients were followed-up until April 2018. Patients were then divided into 2 groups according to age, considering fertile age as ≤ 55 years and postmenopausal age as > 55 years.

Patient clinical information was retrospectively collected from electronic medical records, and included demographic characteristics (gender, age); comorbidities (cardiovascular, renal, hepatic disease); medical therapy [anticoagulants, antiplatelet and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)]; hemoglobin (Hg) at admission and number of units of packed red blood cells (RBC) transfused prior to CE.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. In this study the Mirocam® Video Capsule system was used and the examinations were carried out according to our unit protocol. Patients underwent a clear liquid diet the day before and a fasting period of 12 h before the exam. Oral iron supplements were suspended at least 8 d before the procedure.

After CE ingestion, patients were evaluated 1-2 h after, through realtime visualization and a prokinetic agent was administered if the CE was retained in the stomach. Oral light diet was initiated 4 h after CE ingestion. The recorder was removed 12 h after CE ingestion. Earlier removal of the recorder demanded realtime visualization, confirming a colonic location of CE.

CE cleansing was evaluated according to the qualitative scale developed by Brotz et al[16], and appropriate cleansing was assumed when graduated as excellent, good or fair.

CE findings were classified as positive and negative findings. Positive findings included bleeding without visible lesions, angiodysplasia, varices, hemangioma, ulcer, erosion, eroded polyps, diverticulum with bleeding stigmata or small-bowel tumor.

The DY was defined as the proportion of CE with positive findings compared to the total number of female patients included in the study. The TY was defined as the proportion of patients performing endoscopic treatment compared to the total number of female patients included in the study. Rebleeding, time to rebleed, hospitalization and mortality were also evaluated. Rebleeding episodes were defined as evidence of melena or hematochezia, a drop in Hg ≥ 2 g/dL from baseline, and/or the need for transfusion[17-19].

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23.0. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the patient’s demographic features, clinical characteristics and type of endoscopic findings. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and numeric variables as means. Results are expressed as percentages or mean ± SD for continuous variables.

The χ2 test was used to compare non-continuous variables. The t-test was used to compare continuous variables. The Kaplan-Meier test was used to calculate the time to rebleed. The Log-Rank test was used to compare the time to rebleed between groups. A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

In our study, 183 female patients underwent CE for OGIB, of whom 30.6% were PMW (n = 56) and 69.4% were MW (n = 127). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 64.3 years (SD 15.8). Most patients were referred for occult OGIB (82.5%, n = 151), while 17.5% (n = 32) had overt OGIB. Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) was the most common indication (81.4%, n = 149) followed by melena (9.8%, n = 18), hematochezia (7.7%, n = 14) and positive fecal occult blood test (1.1%, n = 2). Mean Hg value before CE was 9.7 g/dL (SD 2.0). OGIB needing transfusional support was identified in 34.4% (n = 63). Indication for CE, mean Hg value and need of transfusional support are shown in Table 2.

| No. of patients (n = 183) | All | PMW (30.6%, n = 56) | MW (69.4%, n = 127) | P value1 |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 64.3 ± 15.8 | 43.7 ± 8.0 | 74.3 ± 7.9 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 24 (13.1) | 0 (0) | 24 (18.9) | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 20 (10.9) | 3 (5.4) | 17 (13.4) | 0.11 |

| Heart failure | 47 (25.7) | 0 (0) | 47 (37.0) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatic disease | 7 (3.8) | 1 (1.8) | 6 (4.7) | 0.34 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 (18.0) | 2 (3.6) | 31 (34.4) | 0.001 |

| Drugs | ||||

| Anticoagulation | 35 (19.1) | 2 (3.6) | 33 (26.0) | < 0.001 |

| Anti-platelet drugs | 57 (31.1) | 6 (10.7) | 51 (40.2) | < 0.001 |

| NSAIDs | 61 (33.3) | 8 (14.3) | 53 (41.7) | < 0.001 |

| No. of patients (n = 183) | All | PMW(30.6%, n = 56) | MW(69.4%, n = 127) | P value1 |

| Indication for CE | 0.11 | |||

| Occult OGIB | 151 (82.5) | 50 (89.3) | 101 (79.5) | |

| Overt OGIB | 32 (17.5) | 6 (10.7) | 26 (20.5) | |

| IDA | 149 (81.4) | 50 (89.3) | 99 (78.0) | |

| Positive fecal occult blood test | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Hematochezia | 14 (7.7) | 2 (3.6) | 12 (9.4) | |

| Melena | 18 (9.8) | 4 (7.1) | 14 (11.0) | |

| Hb prior to CE, g/dL | 9.7 ( ± 2.0) | 10.4 ( ± 1.7) | 9.3 ( ± 2.1) | 0.001 |

| Need of transfusional support prior to CE | 63 (34.4) | 7 (12.5) | 56 (44.1) | < 0.001 |

Concerning comorbidities, 25.7% had heart failure (n = 47), 18% had atrial fibrillation (n = 33), 13.1% had chronic kidney disease (n = 24) and 3.8% had liver disease (n = 7). Drugs increasing bleeding risk were also evaluated: 19.1% took vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants, 31.2% were medicated with aspirin or thienopyridines and 33.3% took NSAIDs.

CE findings are presented in Table 3. Small bowel cleansing was considered appropriate in 77.6% (n = 142) CE studies. Most patients had positive findings (66.7%, n = 122). Angiodysplasias were the most frequent finding (37.7%, n = 69) followed by ulcers/erosions (9.8%, n = 18) (Figure 1) and mass lesions (8.7%), namely tumors 7.1% [gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and subepitelial lesions] and polyps 1.6%. Blood in the GI tract was observed in 12.6% CE (n = 23), of which in 60.9% no lesions were identified. Angiodysplasias were classified according to the Saurin et al[7] classification system as P1 (66.7%, n = 46) and P2 (33.3%, n = 23). Considering the timing of CE most patients were studied > 14 d (88.0%, n = 161) while a minority underwent CE within the first 14 d (48 h-14 d in 8.2%, n = 15 and < 48 h in 3.8%, n = 7).

| No. of patients (n = 183) | All | PMW (30.6%, n = 56) | MW (69.4%, n = 127) | P value1 |

| Positive Findings | 122 (66.7) | 31 (55.4) | 91 (71.7) | 0.031 |

| CE Findings | ||||

| Angiodysplasias | 69 (37.7) | 12 (21.4) | 57 (44.9) | |

| Ulcers/erosions | 18 (9.8) | 11 (19.6) | 7 (5.5) | |

| Mass lesions | 16 (8.7) | 5 (8.9) | 11 (8.7) | |

| Meckel's diverticulum | 3 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Other | 2 (1.0) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Saurin’s Classification | 0.043 | |||

| P1 | 46 (66.7) | 11 (91.7) | 35 (61.4) | |

| P2 | 23 (33.3) | 1 (8.3) | 22 (38.6) | |

| Blood in GI tract | 23 (12.6) | 3 (5.4) | 20 (15.7) | 0.051 |

| Blood with no lesions | 14 (7.7) | 1 (1.8) | 13 (10.2) | |

| Adequate small bowel cleansing | 142 (77.6) | 44 (78.6) | 56 (44.1) | 0.83 |

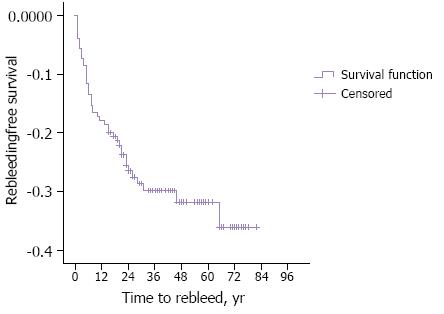

The outcomes of CE are shown in Table 4. The DY was 53.6% (n = 98), TY 12.6% (n = 23). The rebleeding rate was 16.4%, at 1 year, 25.8%, at 3 years and 27.2% at 5 years (Figure 2). The hospitalization rate was 7.1% (n = 13) and the global mortality 1.0% (n = 2) (Table 4).

| No. of patients (n = 183) | All | PMW(30.6%, n = 56) | MW(69.4%, n = 127) | P value1 |

| Diagnostic yield | 98 (53.6) | 17 (30.4) | 81 (63.8) | < 0.001 |

| Therapeutic yield | 23 (12.6) | 1 (1.8) | 22 (17.3) | 0.003 |

| Rebleeding rate | 46 (25.1) | 5 (8.9) | 41 (32.3) | 0.031 |

| Time to rebleed, yr | 0.001 | |||

| 1 yr, 16.4 | 1 yr, 3.6 | 1 yr, 22.0 | ||

| 3 yr, 25.8 | 3 yr, 10.2 | 3 yr, 32.3 | ||

| 5 yr, 27.2 | 5 yr, 10.2 | 5 yr, 34.2 | ||

| Hospitalization rate | 13 (7.1) | 1 (1.8) | 12 (9.4) | 0.063 |

| Mortality rate | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | 0.345 |

The mean age of MW was 73.4 ± 7.9 years and for PMW 43.7 ± 8.0 years. Post-menopausal age was associated with significantly higher comorbidities, namely heart failure (P < 0.001), chronic kidney disease (P < 0.001) and atrial fibrillation (P = 0.001). In this group use of anticoagulants, anti-aggregants and NSAIDs was significantly higher (P < 0.001). Mean Hg level at CE study was lower in MW (9.3 ± 2.1 g/dL) compared to PMW (10.4 ± 1.7 g/dL). The need of blood transfusion before CE was significantly higher in MW (44.1% vs 12.5%) (P < 0.001). IDA was the most common indication in both groups (MW 78.0%; PMW 89.3%).

MW had more frequently positive findings in CE study (71.1% vs 55.4%) (P = 0.031). Angiodysplasias were the most frequent finding in both groups, diagnosed in 44.9% of MW (n = 57) and in 21.4% of PMW (n = 12) (P = 0.003). MW had more frequently lesions with a high bleeding potential, classified as P2 lesions (38.6% vs 8.3%) (P = 0.043). Blood in the GI tract was identified more frequently in MW (15.7%, n = 20) than PMW (5.4%, n = 3) (P = 0.051). Cleansing adequacy was not significantly different between groups (P = 0.83). Timing to CE was not significantly different between groups (P = 0.31). However in MW timing of CE was associated with higher DY (P = 0.002) and TY (0.024). In PMW there timing to CE was not associated with higher DY (P = 0.23) nor TY (P = 0.96).

DY was higher in MW (63.8%, n = 81) than PMW (30.4%, n = 17), and post-menopausal status was significantly associated with higher DY (P < 0.001). TY was significantly higher in MW (17.3%, n = 22) compared to PMW (1.8%, n = 1) (P = 0.003).

The rebleeding rate was significantly higher in MW (P = 0,031). Considering a follow-up period of 1, 3 and 5 years, MW had a significantly higher rebleeding rate (MW 22.0%; 32.3%; 34.2% vs PMW 3.6%; 10.2%; 10.2%) (P = 0.001) (Table 4 and Figure 3).

In the MW group hospitalization due to OGIB was higher (MW-9.4%, PMW-1.8%). Mortality due to OGIB in MW was 1.6%, and there was no death in PMW. There was no significant differences between groups concerning hospitalization (P = 0.063) and mortality (P = 0.345).

OGIB, particularly IDA is the most frequent indication (66%) for CE study[20]. Several studies on the DY of CE in IDA were performed. A systematic review from Koulaouzidis et al[21] showed a pooled CE DY for detection of small bowel findings of 46%. The literature on CE findings and DY in MW and PMW is sparse and in fact evidence from CE DY in OGIB is heterogeneous and lies in two types of study designs: those specifically designed to evaluate the role of CE in patients with IDA and those that investigated patients with a wider range of indications including overt GI bleeding.

In our study, the DY of CE in MW was significantly higher compared to PMW. TY and the rebleeding rate were also higher while time to rebleed was lower in female patients with post-menopausal status. A retrospective study of Garrido-Durán et al[15] documented a DY of CE of 55.0% and 13.7% in MW and PMW respectively. More recently a multicentric retrospective study from Perrod et al[10] obtained similar results, with 34.0% for MW and 15.0% for PMW. These results do not substantially differ from our data, regarding DY of CE in OGIB. Nor Garrido-Duran’s nor Perrod’s studies evaluated TY, rebleeding, time to rebleed, hospitalization nor mortality. In our study MW had more frequently small bowel lesions eligible for endoscopic treatment. There is quite sparse literature in the TY of CE, the rebleeding rate and time to rebleed due OGIB in females comparing pre and post menopause periods. Nevertheless those variable were extensively studied in patients submitted to CE[13,18,19,22,23]. The fact that MW had a higher rate of comorbidities and consumption of anticoagulants, antiplatelet and NSAIDs may partially explain the higher DY, TY and rebleeding rate.

Angiodysplasias were the main findings in CE studies of both groups. Previously published papers comparing PMW and MW had the same outcomes[10,15].

The main achievement of the present study is to bring to evidence the poor results of OGIB investigation through CE in PMW, making clear the need of exclusion of gynecological pathology in this subset of patients[24]. In this population, IDA is often related to gynecological symptoms and gastrointestinal lesions are diagnosed in less than 20% after endoscopic explorations[25].

The present study has some limitations. It has a retrospective design with a small number of patients, therefore a prospective assessment of CE DY in females before and after menopause is warranted. The patients enrolled in the present study were not assessed in a Gynecology appointment in order to confirm menopause diagnosis.

In conclusion PMW with suspected OGIB are less likely to have significant findings in CE. The lower rates of positive findings may be related to gynecological comorbidities, which must be previously excluded. In this group the DY, TY and rebleeding were significantly lower while time to rebleed was higher.

Findings of capsule endoscopy (CE) for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) investigation performed in females may vary substantially according to menopause status. In this paper we estimated and compared diagnostic yield (DY) of CE as well as its therapeutic yield (TY) and clinical outcomes in premenopausal women (PMW) and menopausal women (MW).

Negative CE may lead to increased health costs and delayed diagnosis when performed in patients who were not fully investigated, as OGIB is an exclusion diagnosis.

To compare the DY of CE for OGIB study and correlated this outcome with menopause presence.

The DY, TY, rebleeding rate, hospitalization and mortality were calculated and compared according to menopausal status.

Postmenopausal age was associated with higher DY, need for endoscopic treatment, rebleeding, and hospitalization.

PMW with suspected OGIB is less likely to have significant findings in CE. This suggests that fertile age women should be carefully studied, preferably by a multidisciplinary approach, before CE.

Our study has a retrospective design with a small number of patients, so a prospective comparative assessment of CE findings between PMW and MW with a larger population is warranted. In addition routine evaluation by a Gynecologist may reduce the negative CE burden.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Cui J, Huang LY, Naito Y S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Pennazio M, Spada C, Eliakim R, Keuchel M, May A, Mulder CJ, Rondonotti E, Adler SN, Albert J, Baltes P. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:352-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 482] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Fisher L, Lee Krinsky M, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Friis C, Fukami N, Harrison ME, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue T, Khan K, Maple JT, Strohmeyer L, Sharaf R, Dominitz JA. The role of endoscopy in the management of obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:471-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Enns RA, Hookey L, Armstrong D, Bernstein CN, Heitman SJ, Teshima C, Leontiadis GI, Tse F, Sadowski D. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Use of Video Capsule Endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:497-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute medical position statement on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1694-1696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bini EJ, Micale PL, Weinshel EH. Evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract in premenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia. Am J Med. 1998;105:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Carter D, Maor Y, Bar-Meir S, Avidan B. Prevalence and predictive signs for gastrointestinal lesions in premenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3138-3144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Vahedi K, Gaudin JL, Villarejo J, Florent C, Gay G, Ponchon T. Clinical impact of capsule endoscopy compared to push enteroscopy: 1-year follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:318-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Annibale B, Capurso G, Baccini F, Lahner E, D’Ambra G, Di Giulio E, Delle Fave G. Role of small bowel investigation in iron deficiency anaemia after negative endoscopic/histologic evaluation of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:784-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ribeiro I, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Silva J, Ponte A, Rodrigues J, Carvalho J. What is the long-term outcome of a negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:753-758. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Perrod G, Lorenceau-Savale C, Rahmi G, Cellier C. Diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy in premenopausal and menopausal women with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:e14-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pérez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Esteban-Delgado P, Martínez-Andrés B, Zamora-Nava LE, Rodrigo-Agudo JL, Chacón-Martínez S, Torrella-Cortes E, Shanabo J, López-Higueras A, Muñoz-Bertrán E. Diagnosis agreement between capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding at a referral center. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:495-500. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ribeiro I, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Marqués J, Fernandes C, Carvalho J. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: Which factors are associated with positive capsule endoscopy findings? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:334-339. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Gomes C, Pinho R, Rodrigues A, Ponte A, Silva J, Rodrigues JP, Sousa M, Silva JC, Carvalho J. Impact of the timing of capsule endoscopy in overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding on yield and rebleeding rate - is sooner than 14 d advisable? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;10:74-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pérez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Zamora-Nava LE, Jiménez-García VA, Pérez-Cuadrado-Martínez E. Indications for and diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy in the elderly. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2018;83:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Garrido Durán C, Iyo Miyashiro E, Páez Cumpa C, Khorrami Minaei S, Erimeiku Barahona A, Llompart Rigo A. [Diagnostic yield of video capsule endoscopy in premenopausal women with iron-deficiency anemia]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;38:373-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Brotz C, Nandi N, Conn M, Daskalakis C, DiMarino M, Infantolino A, Katz LC, Schroeder T, Kastenberg D. A validation study of 3 grading systems to evaluate small-bowel cleansing for wireless capsule endoscopy: a quantitative index, a qualitative evaluation, and an overall adequacy assessment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:262-270, 270.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pinho R, Ponte A, Rodrigues A, Pinto-Pais T, Fernandes C, Ribeiro I, Silva J, Rodrigues J, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, Carvalho J. Long-term rebleeding risk following endoscopic therapy of small-bowel vascular lesions with device-assisted enteroscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:479-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Romagnuolo J, Brock AS, Ranney N. Is Endoscopic Therapy Effective for Angioectasia in Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding?: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:823-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jackson CS, Gerson LB. Management of gastrointestinal angiodysplastic lesions (GIADs): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:474-83; quiz 484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liao Z, Gao R, Xu C, Li ZS. Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Koulaouzidis A, Rondonotti E, Giannakou A, Plevris JN. Diagnostic yield of small-bowel capsule endoscopy in patients with iron-deficiency anemia: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:983-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pinho R, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, Mão-de-Ferro S, Ferreira S, Almeida N, Figueiredo P, Rodrigues A, Cardoso H, Marques M, Rosa B. Multicenter survey on the use of device-assisted enteroscopy in Portugal. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:264-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pinho R. The Vanishing Frontiers of Therapeutic Enteroscopy. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2015;22:133-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rodrigues JP, Pinho R, Silva J, Ponte A, Sousa M, Silva JC, Carvalho J. Appropriateness of the study of iron deficiency anemia prior to referral for small bowel evaluation at a tertiary center. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4444-4453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Green BT, Rockey DC. Gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluation of premenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:104-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |