Published online Jan 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i1.30

Peer-review started: October 28, 2017

First decision: November 14, 2017

Revised: December 13, 2017

Accepted: December 29, 2017

Article in press: December 29, 2017

Published online: January 16, 2018

Processing time: 79 Days and 12.9 Hours

To study and describe patients who underwent treatment for gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) with different endoscopic treatment modalities.

We reviewed patients with GAVE who underwent treatment at University of Alabama at Birmingham between March 1, 2012 and December 31, 2016. Included patients had an endoscopic diagnosis of GAVE with associated upper gastrointestinal bleeding or iron deficiency anemia.

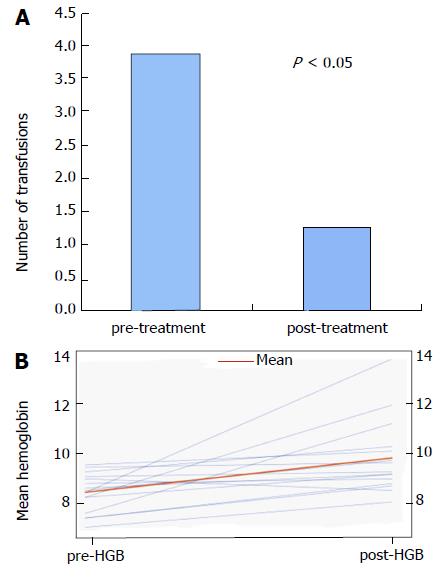

Seven out of 15 patients had classic watermelon description for GAVE, 1/15 with diffuse/honeycomb pattern and 6/15 with nodular GAVE per EGD description. Seven out of 15 patients required multimodal treatment. Four out of six of patients with endoscopically nodular GAVE required multimodal therapy. Overall, mean pre- and post-treatment hemoglobin (Hb) values were 8.2 ± 0.8 g/dL and 9.7 ± 1.6 g/dL, respectively (P ≤ 0.05). Mean number of packed red blood cells transfusions before and after treatment was 3.8 ± 4.3 and 1.2 ± 1.7 (P ≤ 0.05), respectively.

Patients with nodular variant GAVE required multimodal approach more frequently than non-nodular variants. Patients responded well to multimodal therapy and saw decrease in transfusion rates and increase in Hb concentrations. Our findings suggest a multimodal approach may be beneficial in nodular variant GAVE.

Core tip: Over the past several years, treatment for gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) has continued to evolve and the number of available treatments has continued to increase. However, the optimal treatment of GAVE is currently unknown and there currently aren’t any studies comparing every modality. However, it is becoming apparent that patients with severe, diffuse or refractory disease require multimodal therapy. Our case series not only shows that but also that patients specifically with nodular variant GAVE require and respond well to multimodal therapy.

- Citation: Matin T, Naseemuddin M, Shoreibah M, Li P, Kyanam Kabir Baig K, Wilcox CM, Peter S. Case series on multimodal endoscopic therapy for gastric antral vascular ectasia, a tertiary center experience. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(1): 30-36

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i1/30.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i1.30

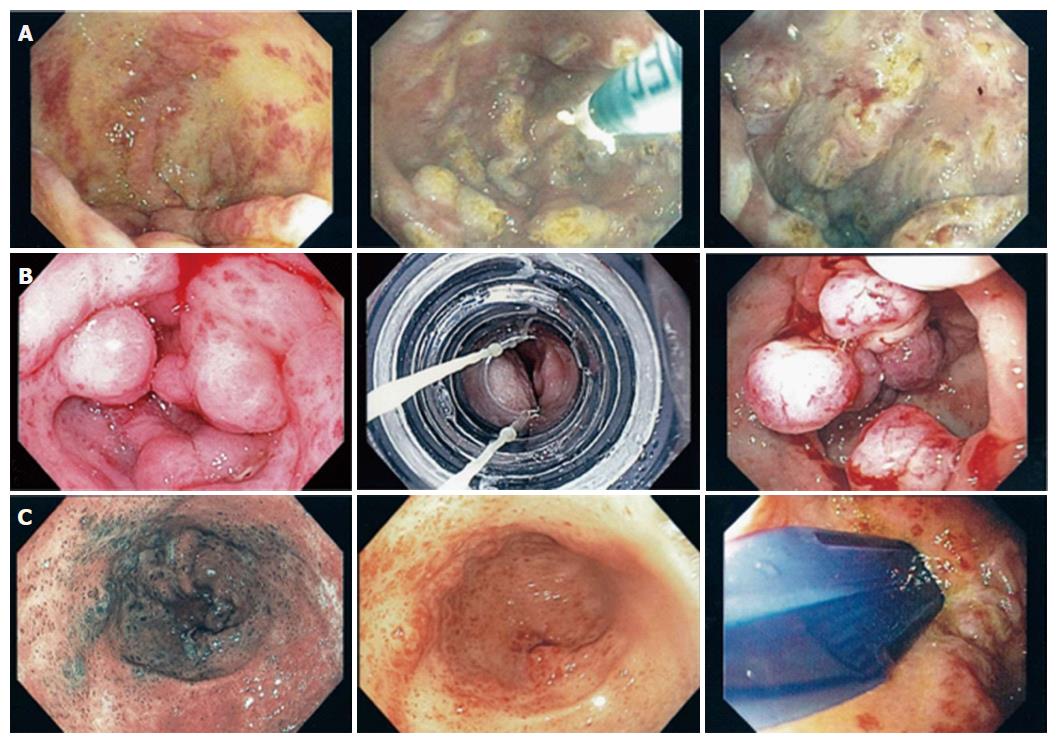

First described in 1953 by Rider et al[1], gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is now a well-recognized cause of chronic upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) accounting for 4% of non-variceal UGIB[2] and an important cause of chronic iron deficiency anemia. Endoscopically, GAVE can appear as organized red spots emanating radially from the pylorus (watermelon stomach), arranged in a diffuse manner (honeycomb stomach), or as nodules[3]. Histologically, GAVE appears as ectatic mucosal capillaries with fibrin thrombi, spindle cell formation and fibrohyalanosis[4]. Immunohistochemical staining for CD61, a platelet marker, further confirms a diagnosis of GAVE[5]. GAVE has been associated with cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune diseases, hypothyroidism, bone marrow transplant and left ventricular assist devices[6-8]. Over the past two decades, many therapeutic options have been implemented for treatment of GAVE including surgical, medical and endoscopic therapies. Data is emerging on the resolution of GAVE following liver transplant in cirrhotics[9]. Endoscopic therapies have rapidly become the mainstays of first line therapy namely with argon plasma coagulation (APC) as the most common modality and more recently with radiofrequency ablation (RFA) using Halo90 catheter[9] and endoscopic band ligation (EBL) both of which have been shown to be safe and effective for GAVE treatment[10,11]. The latter two have been utilized in treatment of severe, diffuse, APC refractory GAVE[10,21]. Furthermore, there has been the advent of BARR χ Through The Scope technique (Covidien, TTS-1100) for RFA, which posits some advantages over the traditional Halo90 system. Despite these advances, the best therapeutic approach has yet to be defined. This case series describes patients who underwent treatment for GAVE with TTS-RFA alone or part of a multimodal approach incorporating other methods such as APC and EBL (Figure 1). We believe that the multimodal approach may be appropriate for certain subsets of patients, namely patients with severe nodular GAVE.

We reviewed patients with GAVE who underwent treatment at University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) between March 1, 2012 and December 31, 2016. Included patients had an endoscopic diagnosis of GAVE with associated UGIB or iron deficiency anemia. Medical history including demographic data and chronic medical conditions associated with GAVE were collected. Patients receiving transfusions for other issues outside of GAVE (i.e., for surgeries) were excluded.

The primary outcomes measured included number of packed red blood cells (pRBC) transfusions required and hemoglobin (Hb) concentrations 6 mo prior to and after initiation of treatment, either with TTS-RFA alone or multimodal therapy. In case of patients in the multimodal group, the same variables were collected 6 mo before and after initiation of an alternative modality (APC, EBL or TTS-RFA). Secondary outcome measures included adverse events, post-treatment adverse events, and number of hospitalizations at University of Alabama (UAB).

Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the procedure. All antiplatelet/anticoagulant therapy was discontinued prior to the procedure. High-resolution endoscopy was performed using white light endoscopy (Figure 2) as well as narrow band imaging. Focal ablation was performed using TTS-RFA catheter. The catheter, consisting of 15.7 mm × 7.5 mm transparent electrode array, was passed through the 2.8 mm working channel of the endoscope. The electrode was the placed in opposition of the GAVE lesions and two consecutive pulses of energy at settings 12-15 J/cm2, 40 W/cm2 were delivered. Circumferential ablation of antral lesions was achieved using the external rotatory function of the catheter (Video 1). Repeat endoscopies and RFA was performed at intervals of 6-8 wk until all lesions appeared healed.

Frequencies (%) were used for categorical variables. For continuous variables, mean ± SD was used. Non-parametric, matched pairs, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to assess differences in pRBC transfusions before and after treatment. Paired T test was used to compare pre and post treatment Hb concentrations. All the analysis were conducted with SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, United States) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Fifteen patients were included in this case series Table 1 describes the demographics. The mean patient age was 62.9 ± 8.7 (range 46-79). Seven out of 15 were women (47%). Included patients underwent a mean of 2.7 ± 1.8 TTS-RFA sessions. TTS-RFA was performed in all patients without adverse events. In addition to TTS-RFA, 7/15 (47%) patients required multimodal approach with APC and/or EBL as well. Average amount of hospitalizations prior to first intervention was 1.4 ± 1.3 and average after initial intervention was 1.1 ± 1.4 (P > 0.05). Average time between initial intervention and second intervention was 2.35 ± 2.27 mo. Overall, mean pre- and post-treatment Hb values were 8.2 ± 0.8 g/dL and 9.7 ± 1.6 g/dL, respectively (P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 3A). Mean number of pRBC transfusions before and after treatment was 3.8 ± 4.3 and 1.2 ± 1.7 (P ≤ 0.05), respectively (Figure 3B).

| Patient | Age | Sex | Race | GAVE associated conditions | Description | Biopsy confirmed? | ASA | On anticoagulation? | Sedation used | MELD-Na |

| 1 | 65 | F | W | Cirrhosis | Watermelon | N | 3 | No | MAC | 15 |

| 2 | 58 | M | W | Cirrhosis | Watermelon | N | 3 | Yes | MAC | 17 |

| 3 | 75 | F | B | LVAD | Watermelon | Y | 4 | No | MAC | n/a |

| 4 | 55 | M | W | Cirrhosis, DM | Nodular | N | 3 | No | MAC | 15 |

| 5 | 79 | F | W | Hypothyroidism | Watermelon | Y | 3 | No | MAC | n/a |

| 6 | 65 | F | W | Cirrhosis | Nodular | Y | 3 | No | MAC | 11 |

| 7 | 70 | F | B | Hypothyroidism | Watermelon | Y | 2 | No | MAC | n/a |

| 8 | 53 | M | W | Cirrhosis | Watermelon | N | 3 | No | MAC | 26 |

| 9 | 70 | M | W | DM | Diffuse | N | 4 | Yes | MAC | n/a |

| 10 | 46 | F | W | CKD | Nodular | Y | 3 | No | MAC | n/a |

| 11 | 60 | M | W | DM | Watermelon | N | 4 | No | MAC | n/a |

| 12 | 68 | F | W | Cirrhosis, DM | Watermelon | N | 3 | No | MAC | 18 |

| 13 | 59 | M | W | Cirrhosis, DM | Nodular | N | 2 | No | MAC | 14 |

| 14 | 62 | M | W | Cirrhosis, DM, LVAD | Nodular | N | 4 | Yes | MAC | 25 |

| 15 | 58 | M | W | Cirrhosis, DM | Nodular | Y | 3 | No | MAC | 23 |

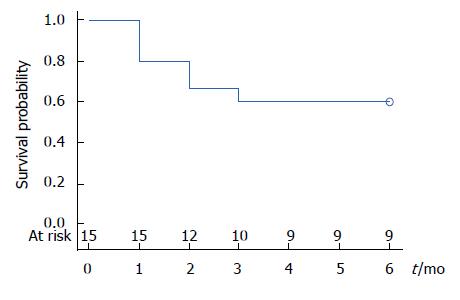

In patients who were primarily treated with TTS-RFA (patients 1-8, n = 8), mean number of sessions was 2.8 ± 1.5. Mean number of transfusions was reduced from 3.0 ± 2.7 to 1.2 ± 1.9 (P > 0.05). Mean Hb increased from 8.3 ± 1.0 g/dL to 9.9 ± 1.2 g/dL (P > 0.05). In patients who required multimodal therapy (patients 9-15, n = 7), mean number of TTS-RFA, APC and EBL sessions was 2.9 ± 2.0, 2.9 ± 3.1 and 1.6 ± 2.2, respectively. The mean number of transfusions decreased from 4.9 ± 5.7 to 1.3 ± 1.7 (P > 0.05) and the mean Hb increased from 8.1 ± 0.7 g/dL to 9.5 ± 2.1 g/dL (P > 0.05). Overall, 8 out of 15 patients were weaned off transfusions (53%) entirely at 6-mo follow-up (Figure 4) and 13/15 saw a decrease in requirements (87%). Only one out of the 15 saw an increase in requirements, while 2 had no change in requirements.

Seven out of 15 patients had classic watermelon description for GAVE, 1/15 with diffuse/honeycomb pattern and 6/15 with nodular GAVE per EGD description. Four out of six of patients with endoscopically nodular GAVE required multimodal therapy. Of the 7 patients requiring multimodal therapy, 4 (57%) had nodular GAVE. Three of these four patients were completely weaned off transfusions in the post-treatment period.

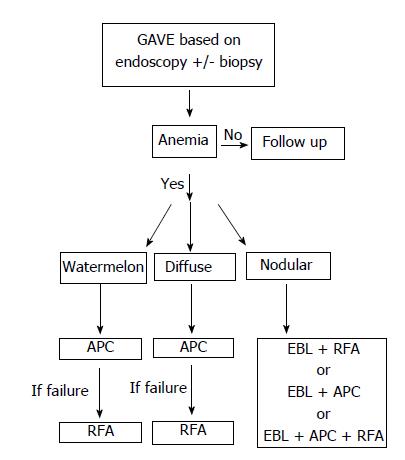

GAVE is an important cause of chronic anemia[7]. Though, often asymptomatic and an incidental finding, it can lead to chronic transfusion dependence. Over the past several years, treatment for GAVE has continued to evolve as the number of available effective therapeutic interventions has increased. These included: YAG laser, APC, EBL, cryotherapy and surgical anterectomy (Figure 5)[10,13-15]. APC is most commonly used but has been associated with sepsis, post-APC bleeding, gastric outlet obstruction and increased incidence of hyperplastic polyps[16-18]. Recently, the BARR x Halo90 system (Covidien, Sunnyvale, CA, United States), which mounts on to the tip of the standard endoscope, has been successfully used for treatment of GAVE[19,20]. Given the fixed positioning of the electrode, the Halo90 catheter requires removal of the endoscope for rotation of the electrode for exact apposition to the mucosa. Repeated intubations are cumbersome and can increase the risk of adverse events, including gastroesophageal junction laceration[21].

The newly introduced TTS-RFA is an improvement over the Halo90 system as it enables the endoscopist to reach all areas of the antrum by internally rotating the catheter without having to remove the endoscope. While it does have a reduced ablative area (1.2 cm2)[22], it delivers up to 120 pulses per session compared to 80 pulses delivered by the Halo90 systems. While TTS-RFA is an effective treatment for GAVE, it may not be sufficient to some subgroups of patients.

EBL has lately been demonstrated as a good alternative to APC especially in refractory cases of GAVE and has been found to have a similar safety profile and per Zepeda’s randomized controlled time performed better than APC[11,24].

The optimal treatment for GAVE is still unknown and currently there are no studies comparing every modality. However, it is becoming more apparent that patients with more severe, diffuse or refractory GAVE would benefit from multimodal therapy[11,18].

From our review, our numbers indicate that patients undergoing single modality treatment with TTS-RFA and multimodality treatment had overall increase in mean Hb concentrations and decreased transfusion requirements in the 6 mo following treatment.

Interesting, of the 6 patients described as having nodular GAVE, 4 required multimodal therapy suggesting perhaps the multimodal approach should be applied to this newly described variant. Outcomes were favorable with multimodal approach in this group showing increased Hb and decreased transfusion requirements. Increased Hb concentrations and subsequent decreased transfusion requirements together decrease patient costs with fewer hospitalizations related to anemia and outpatient costs. We did not see a statistically significant decrease in hospitalizations in our case series and this may be due to a myriad of factors including the fact that hospitalizations may be due to another of patients’ comorbidities. Also, it is difficult to attain data on number of hospitalizations outside of our facility.

There are several limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from this study that need to be addressed. First, this is a small, single center, single operator, retrospective study. Second, GAVE was not confirmed on biopsy on all patients. Third, this study is observational and cannot ascertain if any one therapy is superior over other modalities as study design was not to compare modalities. Lastly, patients were followed for a period of 6 mo after the initiation of treatment While the data is promising, it is not clear if GAVE lesions recur or if patients have worsening anemia after our follow-up period of 6 mo.

In conclusion, patients with nodular variant GAVE required multimodal approach more frequently than non-nodular variants. Patients responded well to multimodal therapy and saw decrease in transfusion rates and increase in Hb concentrations. Our findings suggest a multimodal approach may be beneficial in nodular variant GAVE.

At present, optimal treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is unknown but it is apparent that severe cases require multimodal therapy. The newly discovered nodular variant, from our study, appears to more often require multimodal therapy.

GAVE is an important cause of chronic anemia and can lead to chronic blood transfusion dependence. Having effective treatment is an important for patient quality of life.

Main objectives were to study patients presenting with GAVE and chronic anemia and following outcomes based on type of GAVE as well as type of intervention.

We reviewed patients with GAVE who underwent treatment at University of Alabama at Birmingham. Included patients had an endoscopic diagnosis of GAVE with associated upper gastrointestinal bleeding or iron deficiency anemia. Medical history including demographic data and chronic medical conditions associated with GAVE were collected. Patients receiving transfusions for other issues outside of GAVE (i.e., for surgeries) were excluded.

Seven out of 15 patients had classic watermelon description for GAVE, 1/15 with diffuse/honeycomb pattern and 6/15 with nodular GAVE per EGD description. Seven out of 15 patients required multimodal treatment. Four out of six of patients with endoscopically nodular GAVE required multimodal therapy. Overall, mean pre- and post-treatment hemoglobin (Hb) values were 8.2 ± 0.8 g/dL and 9.7 ± 1.6 g/dL, respectively (P ≤ 0.05). Mean number of pRBC transfusions before and after treatment was 3.8 ± 4.3 and 1.2 ± 1.7 (P ≤ 0.05), respectively.

Patients who received TTS-radiofrequency ablation and patient with multimodal therapy, both had decrease in transfusion requirements and improvement in mean Hb. Our study found that patients with nodular variant GAVE tended to require multimodal therapy more frequently. We believe patients with nodular variant GAVE would benefit from a multimodal approach.

Lessons learned from this study include importance of larger study population. Future directions include involving larger patient pool and possibly attempting a prospective approach based on suggested algorithm.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Akiho H, Chiu CC, Dinc T S- Editor: Chen K L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song XX

| 1. | Rider JA, Klotz AP, Kirsner JB. Gastritis with veno-capillary ectasia as a source of massive gastric hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1953;24:118-123. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Dulai GS, Jensen DM, Kovacs TO, Gralnek IM, Jutabha R. Endoscopic treatment outcomes in watermelon stomach patients with and without portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2004;36:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ito M, Uchida Y, Kamano S, Kawabata H, Nishioka M. Clinical comparisons between two subsets of gastric antral vascular ectasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:764-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Payen JL, Calès P, Voigt JJ, Barbe S, Pilette C, Dubuisson L, Desmorat H, Vinel JP, Kervran A, Chayvialle JA. Severe portal hypertensive gastropathy and antral vascular ectasia are distinct entities in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Westerhoff M, Tretiakova M, Hovan L, Miller J, Noffsinger A, Hart J. CD61, CD31, and CD34 improve diagnostic accuracy in gastric antral vascular ectasia and portal hypertensive gastropathy: An immunohistochemical and digital morphometric study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:494-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Patwardhan VR, Cardenas A. Review article: the management of portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:354-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Fuccio L, Mussetto A, Laterza L, Eusebi LH, Bazzoli F. Diagnosis and management of gastric antral vascular ectasia. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:6-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Alkurdi B, Monkemuller K, Khan AS, Council L, McGuire BM, Peter S. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: a rare manifestation for gastrointestinal bleeding in left ventricular assist device patients--an initial report. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2826-2830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Allamneni C, Alkurdi B, Naseemuddin R, McGuire BM, Shoreibah MG, Eckhoff DE, Peter S. Orthotopic liver transplantation changes the course of gastric antral vascular ectasia: a case series from a transplant center. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:973-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jana T, Thosani N, Fallon MB, Dupont AW, Ertan A. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of refractory gastric antral vascular ectasia (with video). Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E125-E127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Elhendawy M, Mosaad S, Alkhalawany W, Abo-Ali L, Enaba M, Elsaka A, Elfert AA. Randomized controlled study of endoscopic band ligation and argon plasma coagulation in the treatment of gastric antral and fundal vascular ectasia. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:423-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Becq A, Camus M, Rahmi G, de Parades V, Marteau P, Dray X. Emerging indications of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:313-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Naidu H, Huang Q, Mashimo H. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: the evolution of therapeutic modalities. Endosc Int Open. 2014;2:E67-E73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bhatti MA, Khan AA, Alam A, Butt AK, Shafqat F, Malik K, Amin J, Shah W. Efficacy of argon plasma coagulation in gastric vascular ectasia in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:219-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Naga M, Esmat S, Naguib M, Sedrak H. Long-term effect of argon plasma coagulation (APC) in the treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE). Arab J Gastroenterol. 2011;12:40-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kantsevoy SV, Cruz-Correa MR, Vaughn CA, Jagannath SB, Pasricha PJ, Kalloo AN. Endoscopic cryotherapy for the treatment of bleeding mucosal vascular lesions of the GI tract: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:403-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Farooq FT, Wong RC, Yang P, Post AB. Gastric outlet obstruction as a complication of argon plasma coagulation for watermelon stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:1090-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sato T, Yamazaki K, Akaike J. Endoscopic band ligation versus argon plasma coagulation for gastric antral vascular ectasia associated with liver diseases. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baudet JS, Salata H, Soler M, Castro V, Díaz-Bethencourt D, Vela M, Morales S, Avilés J. Hyperplastic gastric polyps after argon plasma coagulation treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE). Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dray X, Repici A, Gonzalez P, Fristrup C, Lecleire S, Kantsevoy S, Wengrower D, Elbe P, Camus M, Carlino A. Radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of gastric antral vascular ectasia. Endoscopy. 2014;46:963-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McGorisk T, Krishnan K, Keefer L, Komanduri S. Radiofrequency ablation for refractory gastric antral vascular ectasia (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:584-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gutkin E, Schnall A. Gastroesophageal junction tear from HALO 90 System: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:105-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Islam RS, Pasha SF, Fleischer DE. Refractory gastric antral vascular ectasia treated by a novel through-the-scope ablation catheter. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:896-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zepeda-Gómez S, Sultanian R, Teshima C, Sandha G, Van Zanten S, Montano-Loza AJ. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: a prospective study of treatment with endoscopic band ligation. Endoscopy. 2015;47:538-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |