Published online Feb 18, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i5.288

Peer-review started: September 28, 2016

First decision: October 31, 2016

Revised: December 4, 2016

Accepted: December 16, 2016

Article in press: December 19, 2016

Published online: February 18, 2017

Processing time: 143 Days and 2.4 Hours

To reduce hepatic and extrahepatic complications of chronic hepatitis C in kidney transplant recipients.

We conducted a systematic review of kidney only transplant in patients with hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis.

The 5 year patient survival of kidney transplant recipients with and without hepatitis C cirrhosis ranged from 31% to 90% and 85% to 92%, respectively. Hepatitis C kidney transplant recipients had lower 10-year survival when compared to hepatitis B patients, 40% and 90% respectively. There were no studies that included patients with virologic cure prior to kidney transplant that reported post-kidney transplant outcomes. There were no studies of direct acting antiviral therapy and effect on patient or graft survival after kidney transplantation.

Data on kidney transplant only in hepatitis C patients that reported inferior outcomes were prior to the development of potent direct acting antiviral. With the development of potent directing acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C with high cure rates studies are needed to determine if patients with hepatitis C, including those with advanced fibrosis, can undergo kidney transplant alone with acceptable long term outcomes.

Core tip: Individuals with chronic hepatitis C with advanced fibrosis and kidney failure who undergo kidney transplant alone are believed to have lower long-term survival. Surprisingly, we have only a few studies with inconsistent results. The concern about isolated-kidney-transplant alone is that the liver disease would progress to decompensated cirrhosis and liver failure in the setting of immunosuppression after kidney transplant. Earlier, interferon was associated with low virologic cure and high adverse events including graft rejection. However, with development of newer directly acting anti-virals we wish to invite our readers to reconsider the need for a combined liver-kidney transplant in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis.

- Citation: Shah NJ, Russo MW. Is it time to rethink combined liver-kidney transplant in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis? World J Hepatol 2017; 9(5): 288-292

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i5/288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i5.288

Patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) cirrhosis undergoing kidney transplantation only have lower post-transplant survival rates compared to recipients without hepatitis C or cirrhosis[1]. After the implementation of the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scoring system for allocating liver transplants, the number of simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation has increased by 300%[2]. Some of these patients may have relatively well compensated cirrhosis and patients with well compensated cirrhosis but kidney failure may receive a MELD score of 20 based upon a creatinine of 4 mg/dL. These patients may have compensated cirrhosis without complications of portal hypertension. Thus, kidney failure, not liver failure may be the driving factor for priority for liver transplant in this subgroup. This is particularly relevant in areas of the country where patients may receive liver transplants at relatively low MELD scores compared to areas with higher demand.

The reason for dual listing patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis and kidney failure who may be well compensated is the concern of decompensation after liver-kidney transplant. Immunosuppressive therapy to prevent rejection increases the titers of HCV RNA and immunosuppression has been associated with accelerated hepatitis injury such as fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C[3]. However, the impact on treating and curing candidates before or after kidney transplant has not been well studied. The high virologic cure rates may have important implications for patients in kidney failure with hepatitis C and advanced liver fibrosis.

The guidelines for liver kidney transplant are conflicting or without detailed recommendations. The AASLD and KDIGO guidelines do not directly address the issue of isolated kidney transplant in the setting of cirrhosis or advanced liver fibrosis. The EASL guidelines state that patients with established cirrhosis and portal hypertension who fail (or are unsuitable for) HCV antiviral treatment, isolated renal transplantation may be contra-indicated and consideration should be given to combined liver and kidney transplantation[4]. Patients with symptomatic or presence of portal hypertension are considered candidates for kidney-liver transplantation[2]. There is no consensus for patients with hepatitis C and periportal fibrosis or bridging fibrosis who are kidney transplant candidates.

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the outcome of hepatitis C cirrhotics undergoing kidney only transplant and suggest areas for further study in patients with hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis who are kidney transplant candidates.

We conducted online electronic searches (published human clinic trials in English) of the National Library of Medicine’s (Bethesda, MD, United States) MEDLINE database, Cochrane Library and manual searches of selected specialty journals to identify any pertinent literature. Three MEDLINE database engines (Ovid, PubMed and EMBASE) were searched using the key words “cirrhosis”, “cirrhotics”, “chronic hepatitis C”, “renal transplantation”, “kidney transplantation”, “mortality”, “graft outcomes”. The references of articles were reviewed for additional articles.

Clinical studies (prospective and retrospective) from the last 20 years on kidney transplant recipients with HCV cirrhosis (both compensated and decompensated) were included. The studies required a minimum of a 1 year post transplant follow-up with information regarding graft and patient survival outcomes.

Studies not published in English or published only in the abstract form were excluded.

To compare post kidney transplant survival in hepatitis C cirrhotics undergoing kidney transplant alone to recipients without hepatitis C and without cirrhosis.

This systematic review was not supported by any pharmaceutical company, governmental agency or other grants.

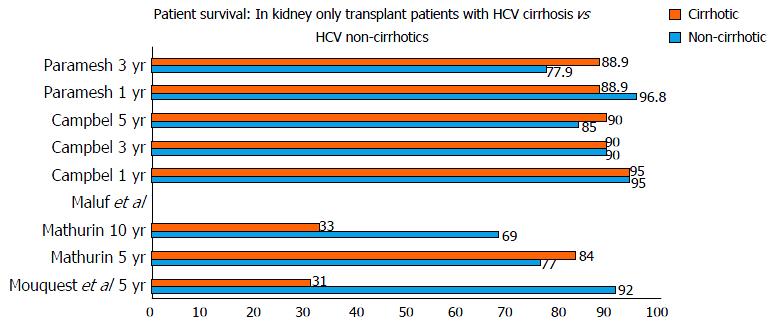

Figure 1 shows studies[5-9] in patients with hepatitis C who underwent kidney transplant only. Five studies were identified that included 2511 patients. Of these 2511 patients, 458 had hepatitis C while 69 were confirmed to have cirrhosis based on a liver biopsy. The mean age ranged from 35 to 57 years with a male to female ratio of 1.73:1. The study by Mathurin et al[6] consisted of 66% Europeans and 31% Africans, while in most of the other studies 66%-79% of the study population was African-American. The most common etiology of kidney disease was diabetes mellitus. Only one study provided the mean MELD score (20.6)[9]. Data on hepatitis C genotyping was not reported in any study. In all the studies the donors were deceased donors. One patient in the Mouquet et al[5] study was coinfected with hepatitis B. Two studies reported the specific immunosuppressive regimen with either cyclosporine or tacrolimus.

The studies reported either 1, 3, 5 or 10 year survival of HCV cirrhotics vs non-cirrhotics. One year and three year survival were available for 3 studies. The 1-year and 3-year patient survival was 88.9% to 95% and 37% to 90% in cirrhotics vs 95% to 96.3% and 76% to 90% in non-cirrhotics. The 5-year and 10-year graft survival was 31%-90% and 33% ± 11% in cirrhotics when compared to 85%-92% and 69% ± 7% in non-cirrhotics.

Mathurin et al[6] reported that the presence of cirrhosis (P = 0.02) and HbsAg positive status (P < 0.0001) were associated with poor 5 and 10-year survival, 84% ± 7% and 33% ± 11%, respectively. Maluf et al[7] demonstrated the Knodell histology score was associated with mortality in hepatitis C kidney transplant patients (P = 0.012).

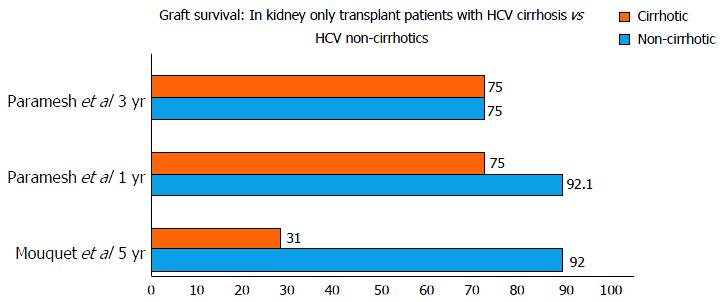

The study by Campbell et al[8] reported that survival after kidney transplant only in recipients with hepatitis C was similar between patients with minimal liver fibrosis compared to patients with advanced fibrosis. Paramesh et al[9] reported kidney transplant alone to be safe in compensated hepatitis C cirrhosis; HR = 1.4, P = 0.7817 compared to graft survival in non-cirrhotics: HR = 0.81, P = 0.758) (Figure 2).

Individuals with chronic hepatitis C with advanced fibrosis and kidney failure who undergo kidney transplant alone are believed to have lower long term survival although there are surprisingly few studies on this patient population. Furthermore, there has not been consistent results among studies reporting outcomes of isolated kidney transplant in hepatitis C infected recipients. The concern about isolated kidney transplant alone in a patients with hepatitis C and advanced liver fibrosis is that the liver disease will progress to decompensated cirrhosis and liver failure in the setting of immunosuppression after kidney transplant. The progression of liver disease from hepatitis C after kidney transplant was of particular concern during the interferon era because of limited therapy for hepatitis C. Interferon is associated with low virologic cure and high adverse events including graft rejection. However, with the development of interferon free regimens and direct acting antiviral agents the need of combined liver-kidney transplant in hepatitis C patients who have hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis needs to be readdressed.

Patients with cirrhosis after kidney transplant may be at a greater risk of immune dysfunction and developing lethal infections because patients with cirrhosis have multiple immunological defects. Cirrhotic patients have reduced cell-mediated immunity[10,11] reduced neutrophil phagocytic ability[12] and impaired macrophage Fc receptor function[13]. In the setting of immunosuppression the risk of infection in patients with cirrhosis is likely higher than without immunosuppression. However, if liver fibrosis regresses then the risk of infection may be reduced. In a 10-year study following 51 kidney transplant recipients with hepatitis C who underwent serial liver biopsies, Kamar et al[14] showed that HCV infection was not associated with worsening liver histology in 50% of patients. Furthermore, there may be regression of liver fibrosis in some patients after kidney transplantation[15]. In fact, Paramesh et al[9] concluded that the presence of cirrhosis in HCV-positive patients is not a significant variable affecting either graft or patient survival.

One strategy is to of treat all chronic hepatitis C patients with direct acting antiviral therapy while waiting for kidney transplant. The regimens that are currently available include sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, sofosbuvir/daclatasvir, and paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir. Each of these regimens may require the addition of ribavirin depending on patient characteristics such as genotype or presence of cirrhosis. Sofosbuvir is renally cleared and not indicated in patients with glomerular filtration rates less than 30 mL/min. Ribavirin is renally cleared and although there is renal dosing for ribavirin it may be associated with a 2-4 g/dL drop in hemoglobin which may not be tolerated in some patients with kidney failure. Thus, given these limitations many patients with kidney failure may not be candidates for therapy with the currently available direct acting antiviral agents. Paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir has been studied in patients with hepatitis C and kidney failure with virologic cure rates exceeding 85%[16]. There are other direct acting antiviral agents in development for hepatitis C patients with kidney failure that will provide additional treatment options for this patient population.

During the era of interferon based regimens for hepatitis C high rates of rejection in kidney transplant recipients was reported. Rejection rates of 40%-60% were reported with interferon based regimens with rare cases of graft loss[17-22]. The mechanism of rejection is believed to be the immune mediated injury from interferon. The direct-acting antiviral agents regimens are interferon free and due not stimulate the T cell response and should not be associated with rejection. The direct acting agents have been studied in liver transplant recipients with virologic cure exceeding 90% and acceptable safety profile with little or no rejection[23-27]. Although there is no theoretical reason to believe the direct acting antiviral agents would be associated with increased risk of kidney rejection this would be studied in clinical trials. Additional important findings from this review include the lack of reporting of relevant data related to hepatitis C including genotype, liver fibrosis, viral load and prior treatment history. Studies of hepatitis C in patients with kidney disease should systematically report these data in a standardized fashion. Furthermore, the number of subjects with hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis was small and it is likely a multicenter study will best demonstrate if there is any difference in outcomes between kidney transplant recipients without hepatitis, with hepatitis C and mild liver fibrosis, and hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis.

We suggest we should treat all chronic hepatitis C patients irrespective of the fibrotic staging; especially those that we anticipate may be on the waiting list for a longer time.

In conclusion, data are lacking or outdated on post renal transplant outcomes in recipients with chronic hepatitis C. There is no substantiated evidence on which to base a decision to perform kidney transplant alone or a kidney-liver transplantation in a patient with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis or well compensated cirrhosis. Given limited resources of organs data are sorely needed so evidence based decisions can be made on how best to allocate kidneys in patients with liver disease. The time has come to conduct a large multicenter trial in kidney transplant candidates and recipients with hepatitis C to determine how organs should best be allocated.

Individuals with chronic hepatitis C with advanced fibrosis and kidney failure who undergo kidney transplant alone are believed to have lower long-term survival. Surprisingly, the authors have only a few studies with inconsistent results. The concern about isolated-kidney-transplant alone is that the liver disease would progress to decompensated cirrhosis and liver failure in the setting of immunosuppression after kidney transplant.

With further research on the use of direct-acting antiviral agents’s (DAA’s) in this subgroup of patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) listed for renal transplant; the authors could come to a consensus to draft acceptable guidelines for better management of this subgroup of patients.

Earlier, interferon was associated with low virologic cure and high adverse events including graft rejection. This has been replaced by newer DAA’s that are safe and potent with fewer side events.

The main objective is to invite hepatologist, transplant hepatologist and transplant nephrologist to consider DAA’s in all HCV patients on the renal transplant list.

DAA’s: Directly acting anti-virals.

This is a correct, well-written review on the different autoimmune forms of liver disease, clinical manifestations and evolution, and treatment.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ikuta S, Kapoor S, Sipos F S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Rao KV, Andersen RC. Long-term results and complications in renal transplant recipients. Observations in the second decade. Transplantation. 1988;45:45-52. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Eason JD, Gonwa TA, Davis CL, Sung RS, Gerber D, Bloom RD. Proceedings of Consensus Conference on Simultaneous Liver Kidney Transplantation (SLK). Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2243-2251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Narang TK, Ahrens W, Russo MW. Post-liver transplant cholestatic hepatitis C: a systematic review of clinical and pathological findings and application of consensus criteria. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1228-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Van Wagner LB, Baker T, Ahya SN, Norvell JP, Wang E, Levitsky J. Outcomes of patients with hepatitis C undergoing simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51:874-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mouquet C, Mathurin P, Sylla C, Benalia H, Opolon P, Coriat P, Bitker MO. Hepatic cirrhosis and kidney transplantation outcome. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mathurin P, Mouquet C, Poynard T, Sylla C, Benalia H, Fretz C, Thibault V, Cadranel JF, Bernard B, Opolon P. Impact of hepatitis B and C virus on kidney transplantation outcome. Hepatology. 1999;29:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maluf DG, Fisher RA, King AL, Gibney EM, Mas VR, Cotterell AH, Shiffman ML, Sterling RK, Behnke M, Posner MP. Hepatitis C virus infection and kidney transplantation: predictors of patient and graft survival. Transplantation. 2007;83:853-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Campbell MS, Constantinescu S, Furth EE, Reddy KR, Bloom RD. Effects of hepatitis C-induced liver fibrosis on survival in kidney transplant candidates. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2501-2507. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Paramesh AS, Davis JY, Mallikarjun C, Zhang R, Cannon R, Shores N, Killackey MT, McGee J, Saggi BH, Slakey DP. Kidney transplantation alone in ESRD patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis. Transplantation. 2012;94:250-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Morgan MY, Mcintyre N. Nutritional aspects of liver disease in Liver and Biliary Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. In: Wright R, Millward-Sadler G, Albert K, Karran S. London 1985; 119. |

| 11. | Hsu CC, Leevy CM. Inhibition of PHA-stimulated lymphocyte transformation by plasma from patients with advanced alcoholic cirrhosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1971;8:749-760. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Rajkovic IA, Williams R. Abnormalities of neutrophil phagocytosis, intracellular killing and metabolic activity in alcoholic cirrhosis and hepatitis. Hepatology. 1986;6:252-262. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Gomez F, Ruiz P, Schreiber AD. Impaired function of macrophage Fc gamma receptors and bacterial infection in alcoholic cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1122-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kamar N, Rostaing L, Selves J, Sandres-Saune K, Alric L, Durand D, Izopet J. Natural history of hepatitis C virus-related liver fibrosis after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1704-1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Roth D, Gaynor JJ, Reddy KR, Ciancio G, Sageshima J, Kupin W, Guerra G, Chen L, Burke GW. Effect of kidney transplantation on outcomes among patients with hepatitis C. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1152-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pockros PJ, Reddy KR, Mantry PS, Cohen E, Bennett M, Sulkowski MS, Bernstein DE, Cohen DE, Shulman NS, Wang D. Efficacy of Direct-Acting Antiviral Combination for Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1 Infection and Severe Renal Impairment or End-Stage Renal Disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1590-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ozgür O, Boyacioğlu S, Telatar H, Haberal M. Recombinant alpha-interferon in renal allograft recipients with chronic hepatitis C. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:2104-2106. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Harihara Y, Kurooka Y, Yanagisawa T, Kuzuhara K, Otsubo O, Kumada H. Interferon therapy in renal allograft recipients with chronic hepatitis C. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:2075. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Rostaing L, Izopet J, Baron E, Duffaut M, Puel J, Durand D. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with recombinant interferon alpha in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1995;59:1426-1431. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chan TM, Lok AS, Cheng IK, Ng IO. Chronic hepatitis C after renal transplantation. Treatment with alpha-interferon. Transplantation. 1993;56:1095-1098. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Fabrizi F, Penatti A, Messa P, Martin P. Treatment of hepatitis C after kidney transplant: a pooled analysis of observational studies. J Med Virol. 2014;86:933-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wei F, Liu J, Liu F, Hu H, Ren H, Hu P. Interferon-based anti-viral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection after renal transplantation: an updated meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Charlton M, Everson GT, Flamm SL, Kumar P, Landis C, Brown RS, Fried MW, Terrault NA, O’Leary JG, Vargas HE. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir Plus Ribavirin for Treatment of HCV Infection in Patients With Advanced Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:649-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 633] [Article Influence: 63.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gutierrez JA, Carrion AF, Avalos D, O’Brien C, Martin P, Bhamidimarri KR, Peyton A. Sofosbuvir and simeprevir for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:823-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pungpapong S, Aqel B, Leise M, Werner KT, Murphy JL, Henry TM, Ryland K, Chervenak AE, Watt KD, Vargas HE. Multicenter experience using simeprevir and sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin to treat hepatitis C genotype 1 after liver transplant. Hepatology. 2015;61:1880-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Saab S, Greenberg A, Li E, Bau SN, Durazo F, El-Kabany M, Han S, Busuttil RW. Sofosbuvir and simeprevir is effective for recurrent hepatitis C in liver transplant recipients. Liver Int. 2015;35:2442-2447. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kwo PY, Mantry PS, Coakley E, Te HS, Vargas HE, Brown R, Gordon F, Levitsky J, Terrault NA, Burton JR. An interferon-free antiviral regimen for HCV after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2375-2382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |