Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1332

Peer-review started: August 31, 2017

First decision: September 26, 2017

Revised: October 15, 2017

Accepted: November 3, 2017

Article in press: November 3, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 118 Days and 16.7 Hours

To evaluate prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis.

This was a register-based study of all patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis during 2008-2012 in Denmark. Hospital contacts with alcohol problems (intoxication, harmful use, or dependence) in the 10-year period preceding the diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis were identified.

In the 10 years prior to diagnosis, 40% of the 7719 alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients and 40% of the 1811 alcoholic pancreatitis patients had at least one prior hospital contact with alcohol problems. Every sixth patient (15%-16%) had more than five contacts. A similar pattern of prior hospital contacts was observed for alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis. Around 30% were diagnosed with alcohol dependence and 10% with less severe alcohol diagnoses. For the majority, admission to somatic wards was the most common type of hospital care with alcohol problems. Most had their first contact with alcohol problems more than five years prior to diagnosis.

There may be opportunities to reach some of the patients who later develop alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis with preventive interventions in the hospital setting.

Core tip: Alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease are preceded by many years of heavy drinking. Hospital contacts with obvious alcohol problems prior to development of alcohol-related liver or pancreatic disease may constitute opportunities for prevention if alcohol problems were to be consistently managed. In this study of all Danish alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis patients, forty percent had at least one previous hospital contact with obvious alcohol problems in the 10 years prior to diagnosis. Most of these patients had their first contact with alcohol problems more than five years prior to diagnosis.

- Citation: Askgaard G, Neermark S, Leon DA, Kjær MS, Tolstrup JS. Hospital contacts with alcohol problems prior to liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis diagnosis. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(36): 1332-1339

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i36/1332.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1332

Alcohol is the single most important cause of liver and pancreatic disease in Western countries[1,2]. Alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease are associated with a considerably mortality risk[3,4], preceded by years of heavy drinking[5,6]. However, among hazardous drinkers reducing or abandoning alcohol consumption can attenuate the risk of full blown disease or death due to alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease[2,7,8]. Since these diseases develop over many years prior to diagnosis, this offers a window of opportunity in which preventive interventions could be implemented.

Hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the period before disease may constitute opportunities for offering alcohol treatment[9,10]. Such hospital contacts include those involving alcohol intoxication (a marker of excessive drinking), harmful alcohol use (a diagnosis used for mild cases of alcohol dependence or when the alcohol use has caused physical or mental disease), and alcohol dependence in more severe cases of alcohol problems[11,12]. In Denmark[13], as in many other countries[14-16], formalised hospital-based alcohol treatment is not available. For example, patients admitted with alcohol withdrawal will be discharged when acute symptoms have been alleviated, without the development of further treatment for underlying alcohol misuse or dependence.

We recently found that patients with hospital contacts with alcohol problems had a more than 10-fold greater rate of alcoholic liver cirrhosis compared to the general population[17]. In the present study, the reverse situation was evaluated; the extent to which patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis have prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems. Earlier studies found that 33%-58% of liver cirrhosis patients had prior hospital contacts indicated by disorders that are sometimes, though not always, associated with alcohol problems such as injuries, non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and epilepsy[18-20]. Hospital contacts with a more specific set of alcohol problems, however, might represent a more feasible opportunity to offer alcohol treatment.

We conducted a nationwide study of all patients who were diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis 2008 to 2012 in Denmark. In these patients, we evaluated the extent of prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the 10 years prior to their diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis.

The study was based on Danish nationwide registries. All Danish citizens have access to free healthcare. The National Patient Register contains data on all somatic hospital admissions since 1977[21]. From 1995 contacts with emergency rooms, outpatient clinics, and psychiatric hospital were recorded. The Danish Register of Causes of Death has recorded causes of death among all Danish citizens since 1970[22]. In all registries, diagnoses are recorded according to the 8th (1971-1993) and 10th (1994-present) revision of the international classification of diseases (ICD)[21].

Information on vital status, civil status, and migration to and from Denmark was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System and education from Statistics Denmark[23]. The registries were linked by a personal identification number, a identifier assigned to all Danish residents at birth since 1968[23].

The study population consisted of all patients with a first diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis in Denmark from 2008 to 2012 (alcoholic liver cirrhosis; ICD-8: 571.0 and ICD-10: K70.3, K70.4 and alcoholic pancreatitis; ICD-10: K85.2, K86.0). Patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis from 1977, when The National Patient Register was initiated, to 2008 were therefore excluded. We combined acute and chronic alcoholic pancreatitis since they are often found together and are both preceded by years of heavy drinking[2,7]. In Denmark, there are restrictions on alcohol sale for young people less than 16-18 years. To ensure 10 years of follow-back before the diagnosis, we excluded patients less than 28 years of age at diagnosis (n = 27). Information from The National Patient Register and Danish Register of Causes of Death were combined. The patients not diagnosed during life but with alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis as their cause of dead were included. Patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis on the same day (n = 65) were assigned to the alcoholic liver cirrhosis group due to the higher mortality associated with this disease[3,24].

Comorbidity was assessed according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index score based on diagnoses made in the course of hospital contacts in the 10 years prior to diagnosis[25]. Psychiatric comorbidity was measured as the number of the following psychiatric diseases (ICD-10 codes): Dementia and organic disorders not caused by alcohol (F00-09), schizophrenia (F20-29), mood disorders (F30-39), neurotic and stress-related (F40-49), behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances (F50-59), personality disorders (F60-69), mental retardation (F70-79), disorders of psychological development (F80-89), and behavioural and emotional disorders (F90-99)[11].

A prior hospital contact with alcohol problems [alcohol intoxication (ICD-10: F10.0), harmful alcohol use (ICD-10: F10.1), or alcohol dependence (ICD-10: F10.2, F10.3, F10.4, F10.5)] was restricted to those occurring in the 10 years before the diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis. However, contacts occurring in the three months prior to diagnosis were excluded to avoid including hospital contacts that might have been precipitated by symptoms of liver or pancreatic disease that were not immediately recognised. A maximum of one hospital contact with alcohol problems per day was included.

Analyses were carried out separately for patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis. We did not calculate confidence limits since we had nationwide data[26]. Assessment of comparability of demographic and medical characteristics between patients with and without prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems were performed using χ2 test for categorical data and t-test for continuous data on age, which followed a normal distribution. Alcohol diagnoses (alcohol intoxication, harmful alcohol use, and alcohol dependence) were assessed as an indicator of the severity of alcohol problems among patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis[12]. We also estimated the type of hospital care of the prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems (somatic, psychiatric, inpatient, emergency room, or outpatient clinic). Finally, we estimated the time in years that had passed from the initial hospital contact with alcohol problems to alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis diagnosis. All analyses were carried out in SAS version 9.4.

From 2008 to 2012, 7719 patients were diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and 1811 were diagnosed with alcoholic pancreatitis in Denmark. Of patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis, 3058 (40%) had at least one hospital contact with alcohol problems within the prior 10 years excluding the three months prior to diagnosis (Table 1). The equivalent number was 719 (40%) for patients with alcoholic pancreatitis. In both patient groups, those with prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems were younger, more often men, more often married, and more often had somatic and psychiatric disease compared to those with no such contacts. For example, of patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis with prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems, 2217 (72%) had no psychiatric comorbidity, 522 (17%) one, and 319 (10%) had two or more. In alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients without prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems, these numbers were 4394 (94%), 203 (4.6%) and 64 (1.4%).

| Characteristic | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis (n = 7719) | Alcoholic pancreatitis (n = 1811) | ||||

| Yes | No | P value | Yes | No | P value | |

| Cohort, n | 3058 (40) | 4661 (60) | 719 (40) | 1092 (60) | ||

| Age, mean (range) | 57 (29-92) | 61 (28-93) | < 0.0001 | 53 (28-90) | 58 (28-92) | < 0.0001 |

| Sex, men | 2144 (70) | 3159 (68) | 0.03 | 562 (78) | 810 (74) | 0.05 |

| Civil status, married | 1338 (44) | 1681 (36) | < 0.0001 | 289 (40) | 345 (32) | 0.000 |

| Education (yr) | 0.001 | 0.38 | ||||

| ≤ 9 | 1479 (48) | 2062 (44) | 342 (48) | 483 (44) | ||

| 9-11 | 1170 (38) | 1950 (42) | 297 (41) | 481 (44) | ||

| ≥ 12 | 409 (14) | 649 (14) | 80 (11) | 128 (12) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | < 0.0001 | 0.02 | ||||

| 0 | 938 (31) | 1890 (41) | 263 (36) | 472 (43) | ||

| 1-2 | 1201 (39) | 1402 (30) | 285 (40) | 391 (36) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 919 (30) | 1369 (29) | 171 (24) | 229 (21) | ||

| Number of psychiatric comorbidities | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||

| 0 | 2217 (73) | 4394 (94) | 478 (67) | 990 (91) | ||

| 1 | 522 (17) | 203 (4.6) | 139 (19) | 68 (6.0) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 319 (10) | 64 (1.4) | 102 (14) | 34 (3.0) | ||

The number of patients not diagnosed during life but having alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis as their cause of death were 875 (11%) and 106 (5.9%).

The 7719 patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis had a total of 38227 hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the prior 10-years (mean of 5.0 contacts). The median number (5th-95th percentiles) of prior contacts was 0 (0-19). The 1811 patients with alcoholic pancreatitis had 8997 prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the prior 10 years (mean of 5.0 contacts). The median number (5th-95th percentiles) of prior contacts was also 0 (0-19) in these patients.

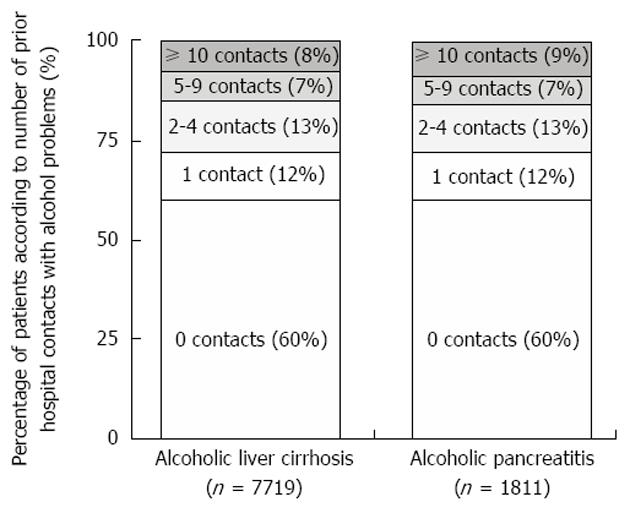

Whereas 60% of the alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients had no prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the prior 10 years, 902 (12%) had one, 992 (13%) had two to four, 509 (7.0%) had five to nine, and 650 (8.0%) had ten or more (Figure 1). The percentages were similar in patients with alcoholic pancreatitis.

Nearly a third of patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence when hospitalized with alcohol problems in the prior 10 years (Table 2). Only 10% had less severe alcohol diagnoses of harmful alcohol use (6.7%-7.5%) or alcohol intoxication (2.3%-2.5%).

| Alcoholic liver cirrhosis (n = 7719) | Alcoholic pancreatitis (n = 1811) | |

| Prior hospital contact with alcohol problems | ||

| No | 4661 (60) | 1092 (60) |

| Yes | 3058 (40) | 719 (40) |

| If yes, the most severe alcohol problem diagnosis recorded | ||

| Intoxication | 184 (2.3) | 46 (2.5) |

| Harmful use | 527 (6.7) | 141 (7.8) |

| Dependence | 2347 (31) | 532 (30) |

| If yes, types of hospital care1 | ||

| Somatic hospital | 2743 (36) | 644 (36) |

| Somatic ward | 2051 (27) | 509 (28) |

| Somatic emergency room | 970 (13) | 226 (12) |

| Somatic outpatient clinic | 1150 (15) | 250 (14) |

| Psychiatric hospital | 1157 (15) | 294 (16) |

| Psychiatric ward | 454 (5.9) | 126 (7.0) |

| Psychiatric emergency room | 775 (10) | 192 (11) |

| Psychiatric outpatient clinic | 431 (5.6) | 125 (6.9) |

More patients had been admitted to a somatic hospital (36%) with alcohol problems than to a psychiatric hospital (15%-16%) in the 10 years prior to diagnosis. Admission to somatic wards with alcohol problems was the most common type of hospital care, which accounted to 2051 (27%) of patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and 509 (28%) of patients with alcoholic pancreatitis.

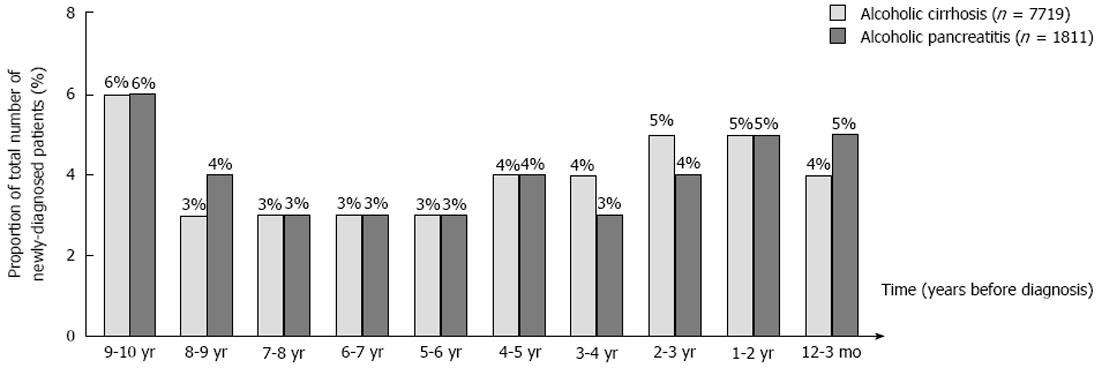

In those patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis who had a prior hospital contact with alcohol problem, more than half had it at least five years before their diagnosis (Figure 2). Only 340 (4%) of all alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients had an initial contact with alcohol problems in the year before diagnosis whereas 980 (14%) had it one two to four years before, 1312 (16%) five to nine years before, and in 426 (6%) ten years before. A similar pattern was seen for those diagnosed with alcoholic pancreatitis.

In the present study, 40% of all Danish patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis diagnosed from 2008 to 2012 had at least one hospital contact with alcohol problems in the prior 10 years before diagnosis. Every sixth patient (15%-16%) had more than five contacts. The pattern of prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems was similar for patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis. Roughly 30% had been given a prior diagnosis of alcohol dependence and 10% had less severe alcohol diagnoses (harmful use and intoxication). Inpatient admission to a somatic ward was the type of hospital care most patients have had with prior alcohol problems. More than half of cases with a prior hospital contact in the preceding 10 years had had their initial alcohol-related contact five or more years prior to diagnosis.

This study has a number of strengths. It covers the entire Danish population for which there is almost complete data on hospital care[21], and cause of death[22]. The alcoholic liver cirrhosis diagnosis in the registry has a high positive predictive value of correctly specifying liver cirrhosis: 78%-92% when compared to information from liver biopsies or clinical evaluation[27,28]. The validity of the alcoholic pancreatitis diagnosis has not been evaluated, but since this diagnosis is managed by gastroenterology specialists in Denmark, we expect the validity to be high[4]. A potential limitation is the validity of the classification of hospital contacts with alcohol problems. These diagnoses are most likely underreported leading to an underestimation of prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems[29].

Prior studies of cirrhosis patients found that 33%-58% had prior health care attendances with disorders that are sometimes associated with alcohol problems[18,20]. This is in accordance with our study where 40% of alcoholic cirrhosis patients had prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems. Our finding that some of the patients with alcohol problems have a considerably high number of repeated contacts due to alcohol has been reported before[12]. To our knowledge, no other study has assessed alcohol problems in patients with alcoholic pancreatitis.

The proportion of alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients with alcohol problems and the severity of these problems found in our study are in line with results from questionnaire-based studies[30-32]. These studies found roughly one third of patients to be moderate or severely alcohol dependent, one third mildly dependent and one third not dependent[30-32]. This underscores the observation that alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients in general have a lower degree of alcohol problems than people seeking treatment for alcohol problems[31,33].

The majority of prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems were with somatic, not psychiatric hospitals. This is likely to reflect the fact that the majority of these cases were precipitated by injuries or non-psychiatric comorbidity[19,20]. That most contacts were as ward admissions rather than emergency room indicate a higher level of disease severity needing longer observation or more complex treatment than could be offered in the emergency room. The relatively few outpatient contacts with alcohol problems might indicate a lower utilization of routine or preventive care in favour of acute hospital admissions when health problems have become more severe, which was observed in heavy drinkers of old age[34].

Finally, in agreement with the long period of heavy drinking that commonly precedes the development of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis[5,6,8], for the majority of patients in our study with prior alcohol contacts, more than five years had passed between their initial contact and diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis.

The implication of our study is that there are opportunities to reach around half of patients who later develop alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis with preventive interventions in the hospital setting[9]. Suggested preventive interventions for liver disease involve implementation of hospital-based alcohol care teams which was shown to reduce alcohol-related admissions[9,35]. It may also involve non-invasive assessment of liver disease[36,37]. Hospital patients with alcohol problems and somatic disease or injury are in particular motivated for alcohol treatment[38-41].

Future studies should assess contacts with obvious alcohol problems in primary care in addition to hospital contacts to compare where patients are most frequently seen with alcohol problems prior to diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis[18,20,42].

About half of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis patients had hospital contacts with alcohol problems prior to diagnosis. There seems to be opportunities to reach some of the patients who later develop alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis with preventive interventions in the hospital setting.

Alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis develop over many years prior to diagnosis, which offers a window of opportunity in which preventive interventions could be implemented. Hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the period before disease may constitute opportunities for offering alcohol treatment. Earlier studies found that 33%-58% of liver cirrhosis patients had prior hospital contacts indicated by disorders that are sometimes, though not always, associated with alcohol problems such as injuries, non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and epilepsy. Hospital contacts with a specific set of alcohol problems (alcohol intoxication, harmful alcohol use, and alcohol dependence) might represent a more feasible opportunity to offer alcohol treatment than disorders associated with alcohol problems. No prior studies evaluated hospital contacts with alcohol problems in patients with alcoholic pancreatitis.

In Denmark, as in many other countries, formalised hospital-based alcohol treatment is not available. Hospitalization with alcohol problems prior to alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis diagnosis may represent an opportunity to offer preventive interventions. In a nationwide study, we evaluated previous hospital contacts with alcohol problems in patients with incident alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis diagnosis.

The objective was to conduct a nationwide study of all patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis 2008 to 2012 in Denmark. In these patients, the extent of prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the 10 years prior to their diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis were evaluated.

This was a nationwide, register-based study of all patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis during 2008-2012 in Denmark. Hospital contacts with alcohol problems (intoxication, harmful use, or dependence) in the 10-year period preceding the diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis were identified. Data was obtained from nationwide registries on hospital contacts and causes of death. This is the first study to evaluate prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems in a nationwide design. Furthermore, no prior studies included psychiatric hospital contacts with alcohol problems. Hospital contacts with alcohol problems occurring in the three months prior to diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis were excluded to avoid including hospital contacts that might have been precipitated by symptoms of liver or pancreatic disease that were not immediately recognised. Alcohol diagnoses (alcohol intoxication, harmful alcohol use, and alcohol dependence) were assessed as an indicator of the severity of alcohol problems among patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis. We also estimated the type of hospital care of the prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems (somatic, psychiatric, inpatient, emergency room, or outpatient clinic). Finally, we estimated the time in years that had passed from the initial hospital contact with alcohol problems to alcoholic liver cirrhosis or pancreatitis diagnosis.

In the 10 years prior to diagnosis, 40% of the 7719 alcoholic liver cirrhosis patients and 40% of the 1811 alcoholic pancreatitis patients had at least one prior hospital contact with alcohol problems. Every sixth patient (15%-16%) had more than five contacts. The 7719 patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis had a total of 38227 hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the prior 10-years (mean of 5.0 contacts). The median number (5th-95th percentiles) of prior contacts was 0 (0-19). The 1811 patients with alcoholic pancreatitis had 8997 prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems in the prior 10 years (mean of 5.0 contacts). The median number (5th-95th percentiles) of prior contacts was also 0 (0-19) in these patients. A similar pattern of prior hospital contacts was observed for alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis. Around 30% were diagnosed with alcohol dependence and 10% with less severe alcohol diagnoses. For the majority, admission to somatic wards was the most common type of hospital care with alcohol problems. Most had their first contact with alcohol problems more than five years prior to diagnosis.

In the present study, 40% of all Danish patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis diagnosed from 2008 to 2012 had at least one hospital contact with alcohol problems in the prior 10 years before diagnosis. Every sixth patient (15%-16%) had more than five contacts. The pattern of prior hospital contacts with alcohol problems was similar for patients diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis. Roughly 30% had been given a prior diagnosis of alcohol dependence and 10% had less severe alcohol diagnoses (harmful use and intoxication). Inpatient admission to a somatic ward was the type of hospital care most patients have had with prior alcohol problems. More than half of cases with a prior hospital contact in the preceding 10 years had had their initial alcohol-related contact five or more years prior to diagnosis.The implication of our study is that there are opportunities to reach around half of patients who later develop alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis with preventive interventions in the hospital setting. Suggested preventive interventions for liver disease involve implementation of hospital-based alcohol care teams which was shown to reduce alcohol-related admissions. It may also involve non-invasive assessment of liver disease. Hospital patients with alcohol problems and somatic disease or injury are in particular motivated for alcohol treatment.

Future studies should assess contacts with obvious alcohol problems in primary care in addition to hospital contacts to compare where patients are most frequently seen with alcohol problems prior to diagnosis of alcoholic liver cirrhosis or alcoholic pancreatitis. In particular, randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate if alcohol treatment in the hospital setting can decrease the incidence of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and alcoholic pancreatitis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Heydtmann M, Gonzalez-Reimers E S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2013;59:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 538] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Muniraj T, Aslanian HR, Farrell J, Jamidar PA. Chronic pancreatitis, a comprehensive review and update. Part I: epidemiology, etiology, risk factors, genetics, pathophysiology, and clinical features. Dis Mon. 2014;60:530-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jepsen P, Ott P, Andersen PK, Sørensen HT, Vilstrup H. Clinical course of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a Danish population-based cohort study. Hepatology. 2010;51:1675-1682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bang UC, Benfield T, Hyldstrup L, Bendtsen F, Beck Jensen JE. Mortality, cancer, and comorbidities associated with chronic pancreatitis: a Danish nationwide matched-cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:989-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barrio E, Tomé S, Rodríguez I, Gude F, Sánchez-Leira J, Pérez-Becerra E, González-Quintela A. Liver disease in heavy drinkers with and without alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakamura Y, Kobayashi Y, Ishikawa A, Maruyama K, Higuchi S. Severe chronic pancreatitis and severe liver cirrhosis have different frequencies and are independent risk factors in male Japanese alcoholics. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:879-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sand J, Lankisch PG, Nordback I. Alcohol consumption in patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2007;7:147-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Williams R, Aspinall R, Bellis M, Camps-Walsh G, Cramp M, Dhawan A, Ferguson J, Forton D, Foster G, Gilmore I. Addressing liver disease in the UK: a blueprint for attaining excellence in health care and reducing premature mortality from lifestyle issues of excess consumption of alcohol, obesity, and viral hepatitis. Lancet. 2014;384:1953-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lid TG, Oppedal K, Pedersen B, Malterud K. Alcohol-related hospital admissions: missed opportunities for follow up? A focus group study about general practitioners’ experiences. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:531-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. 1993;1-267. |

| 12. | Ahacic K, Damström-Thakker K, Kåreholt I. Recurring alcohol-related care between 1998 and 2007 among people treated for an alcohol-related disorder in 1997: a register study in Stockholm County. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Toftdahl NG, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Prevalence of substance use disorders in psychiatric patients: a nationwide Danish population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:129-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McLellan AT, Meyers K. Contemporary addiction treatment: a review of systems problems for adults and adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:764-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Anderson P, Braddick F RJ GA eds. Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA. Available from: http://www.amphoraproject.net. |

| 16. | Ahacic K, Kennison RF, Kåreholt I. Alcohol abstinence, non-hazardous use and hazardous use a decade after alcohol-related hospitalization: registry data linked to population-based representative postal surveys. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Askgaard G, Leon DA, Kjaer MS, Deleuran T, Gerds TA, Tolstrup JS. Risk for alcoholic liver cirrhosis after an initial hospital contact with alcohol problems: A nationwide prospective cohort study. Hepatology. 2017;65:929-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Verrill C, Smith S, Sheron N. Are the opportunities to prevent alcohol related liver deaths in the UK in primary or secondary care? A retrospective clinical review and prospective interview study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2006;1:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rehm J. The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34:135-143. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Otete HE, Orton E, Fleming KM, West J. Alcohol-attributable healthcare attendances up to 10 years prior to diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis: a population based case-control study. Liver Int. 2016;36:538-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:30-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 3315] [Article Influence: 236.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:26-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 944] [Cited by in RCA: 1384] [Article Influence: 98.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:541-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1701] [Cited by in RCA: 2664] [Article Influence: 242.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ramesh H. Natural history of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1777-1778. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash TL, Sørensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 733] [Cited by in RCA: 1010] [Article Influence: 72.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Thygesen LC, Ersbøll AK. When the entire population is the sample: strengths and limitations in register-based epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:551-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Becker U, Deis A, Sørensen TI, Grønbaek M, Borch-Johnsen K, Müller CF, Schnohr P, Jensen G. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology. 1996;23:1025-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Sørensen HT. Alcoholic cirrhosis in Denmark - population-based incidence, prevalence, and hospitalization rates between 1988 and 2005: a descriptive cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Søgaard M, Heide-Jørgensen U, Nørgaard M, Johnsen SP, Thomsen RW. Evidence for the low recording of weight status and lifestyle risk factors in the Danish National Registry of Patients, 1999-2012. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wodak AD, Saunders JB, Ewusi-Mensah I, Davis M, Williams R. Severity of alcohol dependence in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:1420-1422. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Smith S, White J, Nelson C, Davies M, Lavers J, Sheron N. Severe alcohol-induced liver disease and the alcohol dependence syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:274-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hatton J, Burton A, Nash H, Munn E, Burgoyne L, Sheron N. Drinking patterns, dependency and life-time drinking history in alcohol-related liver disease. Addiction. 2009;104:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stokkeland K, Hilm G, Spak F, Franck J, Hultcrantz R. Different drinking patterns for women and men with alcohol dependence with and without alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Merrick ES, Hodgkin D, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Panas L, Ryan M, Blow FC, Saitz R. Older adults’ inpatient and emergency department utilization for ambulatory-care-sensitive conditions: relationship with alcohol consumption. J Aging Health. 2011;23:86-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | British T, Nhs B, Trust F. Quality and Productivity: Proven Case Study Alcohol care teams: reducing acute hospital admissions and improving quality of care Quality and Productivity: Proven Case Study. 2014;. |

| 36. | Sheron N, Moore M, O’Brien W, Harris S, Roderick P. Feasibility of detection and intervention for alcohol-related liver disease in the community: the Alcohol and Liver Disease Detection study (ALDDeS). Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e698-e705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cirrhosis in over 16s. Assessment and management. 2016;. |

| 38. | Pedersen B, Oppedal K, Egund L, Tønnesen H. Will emergency and surgical patients participate in and complete alcohol interventions? A systematic review. BMC Surg. 2011;11:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bertholet N, Cheng DM, Palfai TP, Saitz R. Factors associated with favorable drinking outcome 12 months after hospitalization in a prospective cohort study of inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1024-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Apodaca TR, Schermer CR. Readiness to change alcohol use after trauma. J Trauma. 2003;54:990-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Bombardier CH, Rimmele CT. Alcohol use and readiness to change after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1110-1115. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Otete HE, Orton E, West J, Fleming KM. Sex and age differences in the early identification and treatment of alcohol use: a population-based study of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcohol. 2008;43:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |