Published online Dec 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1322

Peer-review started: August 30, 2017

First decision: September 21, 2017

Revised: October 12, 2017

Accepted: November 11, 2017

Article in press: November 12, 2017

Published online: December 28, 2017

Processing time: 121 Days and 18.7 Hours

To characterize the survival of cirrhotic patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and to ascertain the factors predicting the achievement of disease control (DC).

The cirrhotic patients with BCLC stage C HCC evaluated by the Hepatocatt multidisciplinary group were subjected to the investigation. Demographic, clinical and tumor features, along with the best tumor response and overall survival were recorded.

One hundred and ten BCLC stage C patients were included in the analysis; the median overall survival was 13.4 mo (95%CI: 10.6-17.0). Only alphafetoprotein (AFP) serum level > 200 ng/mL and DC could independently predict survival but in a time dependent manner, the former was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality within the first 6 mo of follow-up (HR = 5.073, 95%CI: 2.159-11.916, P = 0.0002), whereas the latter showed a protective effect against death after one year (HR = 0.110, 95%CI: 0.038-0.314, P < 0.0001). Only patients showing microvascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread recorded lower chances of achieving DC (OR = 0.263, 95%CI: 0.111-0.622, P = 0.002).

The BCLC stage C HCC includes a wide heterogeneous group of cirrhotic patients suitable for potentially curative treatments. The reverse and time dependent effect of AFP serum level and DC on patients’ survival confers them as useful predictive tools for treatment management and clinical decisions.

Core tip: Refining the prognosis of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is crucial to select patients that can get benefit from and be suitable for locoregional or surgical treatments. This study confirms that high alphafetoprotein serum level and DC are the best predictors of mortality for BCLC C patients, highlighting that the effect of these two variables is reverse and dynamic, in a time dependent manner. Outstandingly, performance status has not been found to be a strong predictor of mortality. According to our results, curative treatments should not be “a priori” excluded in a subset of BCLC stage C patients with favorable prognostic factors.

- Citation: Ponziani FR, Spinelli I, Rinninella E, Cerrito L, Saviano A, Avolio AW, Basso M, Miele L, Riccardi L, Zocco MA, Annicchiarico BE, Garcovich M, Biolato M, Marrone G, De Gaetano AM, Iezzi R, Giuliante F, Vecchio FM, Agnes S, Addolorato G, Siciliano M, Rapaccini GL, Grieco A, Gasbarrini A, Pompili M. Reverse time-dependent effect of alphafetoprotein and disease control on survival of patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(36): 1322-1331

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i36/1322.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i36.1322

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been recognized as a major health problem, as it ranks third among the leading causes of death due to cancer and is the sixth most common tumor with a worldwide occurrence[1].

While there are several options available for the treatment of HCC, their choice most likely depends on tumor stage, impairment of normal liver function, patient’s performance status (PS) and comorbidities. The most widely accepted staging system for HCC is the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC), which was based on the patients clinical features along with tumor-related variables and therefore categorized five different stages with progressively worsening prognosis and different treatment options[1,2].

The patients with an advanced HCC belong to the BCLC stage C, which includes tumors with macrovascular invasion, and/or extrahepatic spread and/or mild cancer-related symptoms, PS 1-2 (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group), and mild to moderate liver function impairment (Child-Pugh stage A-B). The only therapeutic option recommended for BCLC stage C HCC is the drug sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that has been reported to extend the overall survival of patients up to nearly 3 mo[3].

Given the higher number of heterogeneous and complex cases encountered in the field-practice, the BCLC classification is often not exhaustive, and the increasing number of new therapeutic options and their combinations makes difficult to strictly adhere to BCLC suggestions. This has been largely demonstrated in other categories of patients such as those belonging to the BCLC stage B group, who had not been subjected to transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), the treatment recommended by the BCLC algorithm, in more than one third of cases[4-6].

The BCLC stage C HCC encompasses a wide spectrum of tumors and patients’ with different characteristics that may get benefit from and be suitable for locoregional or surgical treatments[7-9]. Nonetheless, in this stage too, the universal administration of sorafenib to the patients following the BCLC algorithm may sometimes be arguable and other therapeutic options could be explored according to patient’s individual conditions.

The current study is principally aimed at characterizing the prognosis of cirrhotic patients with BCLC stage C HCC as assessed by a multidisciplinary team in an Italian tertiary care center. In addition to this, the other objective is the identification of the factors predicting the achievement of disease control (DC).

The present study was performed at the Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy. The prospective database of the Hepatocatt multidisciplinary group, containing clinical, tumor and outcome data of all liver cancer subjects evaluated in the seven years at our Institute was reviewed, and the cohort of cirrhotic patients with BCLC stage C HCC were selected as the prime object of the investigation.

The following criteria were adopted for the selection of patients: PS grade ≤ 2; Child-Pugh class A or B; tumor macrovascular invasion (mainly portal vein and/or hepatic veins and/or inferior vena cava); and/or extrahepatic spread. The HCC was diagnosed by multiphasic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or by ultrasound-guided biopsy, as per the guidelines of European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[1,2]. Based on the liver function and patients’ characteristics, the modalities of HCC treatment were decided by the Hepatocatt multidisciplinary board, comprising of hepatologists, hepatobiliary and transplant surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists. The imaging criteria (CT and/or MRI) for assessing the tumor response established by mRECIST were followed[10]. For individual patient, the treatment outcome was documented; DC was achieved in those patients who acquired a stable disease (SD), partial response (PR) or complete response (CR) as the best treatment outcome.

The patients’ survival was the measure of success as primary outcome. The follow-up time was defined as the number of months from the entry in the BCLC stage C till their death or last visit. The factors that could predict the achievement of DC were also investigated as secondary endpoint.

Statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric tests due to the non normal distribution of data. The continuous variables were expressed as median and range, while the categorical variables as frequencies and percentages.

Pre-treatment variables [Child-Pugh score, PS, number and maximum size of HCC lesions, presence of macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spread, alphafetoprotein (AFP) serum level, NIACE score value[11], and diabetes] and post-treatment variables (the number of treatments received after entry in the BCLC stage C and the achievement of DC) were considered as prognostic factors of patients’ survival. The univariate analysis of survival estimates was performed using the Kaplan-Meier curve and the log-rank test was applied to check the differences between the groups. The variables with a P < 0.100 were included in the Cox proportional hazard regression model for the multivariate survival analysis, adjusting for gender and age.

The assumption of proportionality was confirmed by plotting the scaled Schoenfeld residuals over the time [log hazard ratio (beta) over time] and by performing a non-proportionality test (Pearson correlation test) for the overall model and for each covariate of the model. Interaction terms were subsequently introduced in the analysis for that factors that varied significantly over time. Fisher’s exact test and binomial logistic regression were performed to identify the predictors of DC among pre- and post-treatment variables.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the R statistics program version 3.1.2. All statistical tests were two-sided and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

A total of 1030 records of liver cancer patients evaluated between May 2008 and May 2015 were reviewed, of which, 146 non-HCC liver tumors and 774 HCC in BCLC stage other than C (0, A, B or D) were disqualified from the study. Therefore, finally, 110 patients classified as BCLC stage C were included in the investigation. Clinical data and tumor characteristics of the study population are given in Table 1.

| Variable | Overall (110) |

| Age (yr) | 67.5 (41-80) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 91 (82.7) |

| Female | 19 (17.3) |

| Etiology of liver disease | |

| Viral (HBV/HCV/HBV and HCV) | 70 (63.6) |

| Alcohol | 17 (15.5) |

| NASH/NAFLD | 14 (12.7) |

| Viral and alcohol | 9 (8.2) |

| PS | |

| 0 | 33 (30) |

| 1 | 64 (58.2) |

| 2 | 13 (11.8) |

| Diabetes | |

| No | 87 (79.1) |

| Yes | 23 (20.9) |

| Child-Pugh score | |

| A | 82 (74.5) |

| B | 28 (25.5) |

| N nodules | |

| Single | 35 (31.8) |

| 2-3 | 20 (18.2) |

| > 3 or infiltrating | 55 (50) |

| Maximum size | |

| ≤ 5 cm | 56 (50.9) |

| > 5 cm | 54 (49.1) |

| Macrovascular invasion | |

| No | 60 (54.5) |

| Yes | 50 (45.5) |

| Extrahepatic spread | |

| No | 91 (82.7) |

| Yes | 19 (17.3) |

| Macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread | |

| No | 49 (44.5) |

| Yes | 61 (55.5) |

| NIACE | |

| ≤ 3 | 84 (76.4) |

| > 3 | 26 (23.6) |

| AFP | |

| ≤ 200 ng/mL | 74 (67.3) |

| > 200 ng/mL | 36 (32.7) |

| Treatment before BCLC C diagnosis | |

| No | 53 (48.2) |

| Yes | 57 (51.8) |

| Type of treatment before BCLC C diagnosis (one or more per patient) | |

| TACE | 35 |

| Surgical resection | 20 |

| RFA | 18 |

| Sorafenib | 13 |

| PEI | 11 |

| TACE + RFA | 8 |

| TARE | 4 |

| DSM-TACE | 1 |

| Number of treatments after BCLC C diagnosis | |

| None | 22 (20) |

| Single | 32 (29.1) |

| Multiple | 56 (50.9) |

| Type of treatment after BCLC C diagnosis (one or more per patient) | |

| Sorafenib | 53 |

| TACE | 25 |

| TARE | 18 |

| Second line systemic agent | 15 |

| PEI | 12 |

| DSM-TACE | 5 |

| LT | 3 |

| RFA | 1 |

| Best tumor response | |

| CR | 10 (9.1) |

| PR | 21 (19.1) |

| SD | 12 (10.9) |

| PD | 67 (60.9) |

| DC | |

| No | 67 (60.9) |

| Yes | 43 (39.1) |

Out of 110 BCLC stage C patients included in the investigation, only 32 received a single treatment and 56 more than once, whereas 22 of them received only best supportive care due to the inadequate liver function. Sorafenib was the most common choice of treatment, followed by TACE, TARE, and second-line systemic agents in patients who were either intolerant to sorafenib or sorafenib failed for them (Table 1). In selected cases, PEI or RFA in combination with other treatments and DSM-TACE were also performed; three PS 1 patients without macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spread and with tumors complying the Milan criteria after effective downstaging (when needed) underwent liver transplant (LT). The best-succeeded response was CR in 9.1% of cases, PR in 19.1%, SD in 10.9%, and PD in 60.9% of cases; overall, 43 (39.1%) patients obtained DC.

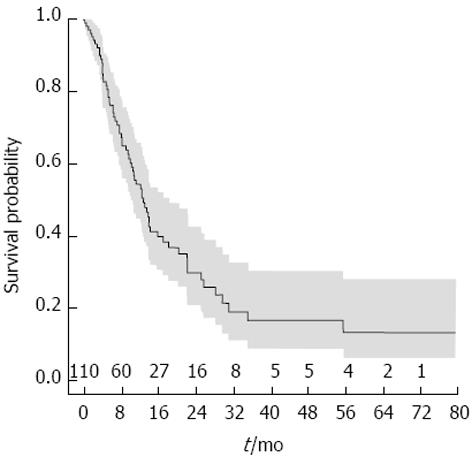

After a median follow-up of 22.9 mo (95%CI: 17.3-38.1), the cumulative median survival of the overall population was 13.4 mo (95%CI: 10.6-17.0, Figure 1). A total of 66 patients died and the most prevailing cause of death was attributed to tumor progression (50/66; 75.7%), followed by liver function failure (13/66; 19.7%), while in the remaining 3 patients, the death was caused by sepsis, post LT complications and bone fracture.

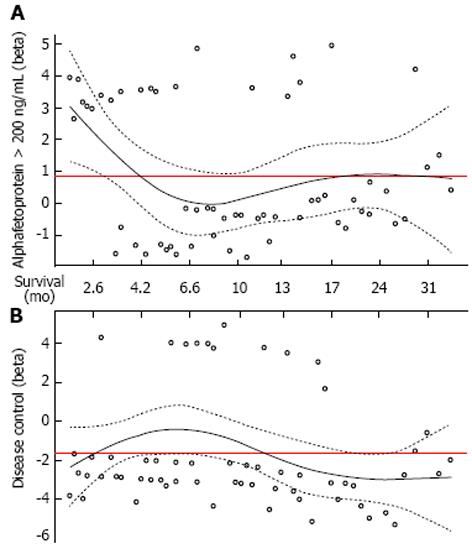

At univariate analysis, AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL, tumor size > 5 cm, the presence of macrovascular invasion, the presence of macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread as pre-treatment factors and the absence of DC as post-treatment factor were considered to be correlated with a worse outcome (Table 2). However, at the multivariate Cox regression, only AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL and DC were independent predictors of mortality (HR = 2.194, 95%CI: 1.249-3.855, P = 0.006 and HR = 0.190, 95%CI: 0.098-0.367, P < 0.0001, respectively). In particular, the effect of these two variables was reverse in a time dependent manner, as depicted by plotting the log hazard ratios (beta) over time (Figure 2). In the first 6 mo of follow-up, serum AFP > 200 ng/mL was directly associated with lower chances of survival, but the effect declined subsequently. Conversely, the favorable prognostic impact of DC curtailed in the early-intermediate period and became noticeable after 1 year of follow-up.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Survival time (mo) | P value | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||

| < 65 yr | 13.9 | 0.903 | - | - |

| ≥ 65 yr | 13.8 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 13 | 0.900 | - | - |

| Female | 14.2 | |||

| PS | ||||

| 0 | 10.3 | 0.128 | - | - |

| 1/2 | 13.9 | |||

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 13 | 0.813 | - | - |

| Yes | 13.8 | |||

| Child-Pugh score | ||||

| A | 13.4 | 0.957 | - | - |

| B | 12.8 | |||

| N nodules | ||||

| Single | 13.8 | 0.776 | - | - |

| 2-3 | 13.4 | |||

| Multinodular/infiltrating | 13 | |||

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 13.9 | 0.0221 | 1 | 0.275 |

| > 5 cm | 9.9 | 1.357 (0.784-2.349) | ||

| Macrovascular invasion | ||||

| No | 15.8 | 0.0141 | 1 | 0.866 |

| Yes | 9.5 | 1.095 (0.379-3.162) | ||

| Extrahepatic spread | ||||

| No | 11.2 | 0.274 | - | - |

| Yes | 6.7 | |||

| Macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread | ||||

| No | 13.8 | 0.0081 | 1 | 0.429 |

| Yes | 6.3 | 1.547 (0.523-4.571) | ||

| AFP | ||||

| ≤ 200 ng/mL | 15.8 | 0.00021 | 1 | 0.0061 |

| > 200 ng/mL | 6.3 | 2.194 (1.249-3.855) | ||

| DC | ||||

| No | 7.6 | < 0.00011 | 1 | < 0.00011 |

| Yes | 15.8 | 0.190 (0.098-0.367) | ||

| NIACE score | ||||

| ≤ 3 | 13.8 | 0.515 | - | - |

| > 3 | 6.7 | |||

A term of interaction of these two covariates with time was then introduced in the Cox model and hazard ratios were reported by each time interval (≤ 6 mo, 7-12 mo, > 12 mo; Table 3). The AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL was significantly associated with higher risk of mortality within the first 6 mo of patients’ entry into the BCLC stage C (≤ 6 mo, HR = 5.073, 95%CI: 2.159-11.916, P = 0.0002). Conversely, DC exercised a significant protective effect in long-term phase (> 12 mo, HR = 0.110, 95%CI: 0.038-0.314, P < 0.0001).

| Variable | Multivariate analysis | |

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Macrovascular invasion | ||

| No | 1 | 0.917 |

| Yes | 1.066 (0.412-2.762) | |

| Macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread | ||

| No | 1 | 0.366 |

| Yes | 1.552 (0.584-4.124) | |

| Tumor size | ||

| ≤ 5 cm | 1 | 0.266 |

| > 5 cm | 1.369 (0.786-2.382) | |

| AFP (> 200 ng/mL vs ≤ 200 ng/mL) | ||

| < 6 mo | 5.073 (2.159-11.916) | 0.00021 |

| 7-12 mo | 0.948 (0.275-3.267) | 0.932 |

| > 12 mo | 1.698 (0.620-4.648) | 0.303 |

| DC (Yes vs No) | ||

| < 6 mo | 0.220 (0.075-0.650) | 0.096 |

| 7-12 mo | 0.463 (0.181-1.189) | 0.109 |

| > 12 mo | 0.110 (0.038-0.314) | < 0.00011 |

There were also identified 5 patients who had unexpectedly longer survival (above the 95th percentile; median 63.3 mo). The characteristics of those subjects have been described in Table 4; outstandingly, in most of the cases (3/5) PS 1-2 was the major cause for categorizing them in BCLC stage C. Pre-treatment AFP serum level was ≤ 200 ng/mL in all these patients; and two of them showed tumor macrovascular invasion without any extrahepatic spread. In one case Sorafenib, and in another TARE was prescribed; whereas, in the remaining three patients, curative treatments (LT), DSM-TACE or second-line systemic therapies were administered. Remarkably, DC was achieved in all these long-term survivors.

| PT | Gender | Age | Etiology | PS | Child-Pugh | AFP > 200 ng/mL | No. of nodules | Maximum size | Macrovascular invasion | Extrahepatic spread | Diabetes | Pre-BCLC C treatments | Post-BCLC C treatments | Best response | DC | Survival (mo) | Status |

| PT3 | M | 65 | HBV | 1 | A | No | Infiltrating | Infiltrating | Yes | No | No | None | Sorafenib | CR | Yes | 79.4 | Alive |

| PT10 | M | 73 | HCV | 1 | A | No | > 3 | 18 | No | No | No | TACE, resection, sorafenib | Second line systemic agent, DSM-TACE (2) | SD | Yes | 63.3 | Alive |

| PT27 | M | 58 | HBV | 2 | B | No | 2 | 19 | No | No | No | RFA, TACE | LT | CR | Yes | 67.1 | Alive |

| PT53 | M | 63 | Alcohol | 1 | B | No | > 3 | 50 | No | No | No | None | TACE (4), TACE + RFA (1), LT | CR | Yes | 58.9 | AliVe |

| PT54 | M | 65 | HCV | 0 | A | No | Single | 40 | Yes | No | Yes | None | TARE (2) | SD | Yes | 38.1 | Alive |

The examination of factors associated with DC was the second landmark of the study (Table 5). The patients who achieved DC (43/110; 39.1%) were illustrated by small-size tumors (> 5 cm: 13/43, 30.2% vs 41/67, 61.2%; P = 0.002), a lower frequency of macrovascular invasion (11/43, 25.6% vs 39/67, 58.2%; P = 0.0009), extrahepatic spread (3/43, 7% vs 16/67, 23.9%; P = 0.036) and of macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread (14/43, 32.6% vs 47/67, 70.1%; P = 0.0001), lower AFP serum level (> 200 ng/mL: 8/43, 18.6% vs 28/67, 41.8%; P = 0.013) and more frequently received at least one treatment (39/43, 90.7% vs 49/67, 73.1%; P = 0.029). However, only the presence of macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread was independently associated with reduced likelihoods of achieving DC (OR 0.263, 95%CI: 0.111-0.622, P = 0.002). It is important to mention that among the 61 patients who showed macrovascular invasion and/or metastases, 44 (72.1%) received treatment and this proportion was significantly lower than that of patients showing intrahepatic disease without vascular involvement (44/49, 89.8%, P = 0.029).

| Variable | DC (43) | No DC (67) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

| P value | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |||

| Age | |||||

| < 65 yr | 15 | 27 | 0.229 | - | |

| ≥ 65 yr | 28 | 40 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 35 | 56 | 0.471 | - | |

| Female | 8 | 11 | |||

| PS | |||||

| 0 | 37 | 60 | 0.06 | - | |

| 1/2 | 6 | 7 | |||

| Diabetes | |||||

| No | 34 | 53 | 0.653 | - | |

| Yes | 9 | 14 | |||

| Child-Pugh score | |||||

| A | 31 | 51 | 0.524 | - | |

| B | 12 | 16 | |||

| N nodules | |||||

| Single | 13 | 22 | 0.078 | ||

| 2-3 | 11 | 9 | - | ||

| Multinodular/infiltrating | 19 | 36 | |||

| Tumor size | |||||

| ≤ 5 cm | 30 | 26 | 0.0061 | 1 | 0.298 |

| > 5 cm | 13 | 41 | 0.617 (0.236-1.610) | ||

| Macrovascular invasion | |||||

| No | 32 | 28 | 0.00031 | - | - |

| Yes | 11 | 39 | |||

| Extrahepatic spread | |||||

| No | 40 | 51 | 0.021 | - | - |

| Yes | 3 | 16 | |||

| Macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread | |||||

| No | 29 | 20 | < 0.00011 | 1 | 0.0021 |

| Yes | 14 | 47 | 0.263 (0.111-0.622) | ||

| AFP | |||||

| ≤ 200 ng/mL | 35 | 39 | 0.0081 | 1 | 0.179 |

| > 200 ng/mL | 8 | 28 | 0.461 (0.169-1.258) | ||

| NIACE score | |||||

| ≤ 3 | 34 | 50 | 0.502 | - | |

| > 3 | 9 | 17 | |||

| Treatment after BCLC C diagnosis | |||||

| No | 4 | 18 | 0.041 | 1 | 0.270 |

| Yes | 39 | 49 | 0.531 (0.147-1.917) | ||

The BCLC staging system is the most widely used approach for the therapeutic and prognostic classification of cirrhotic patients with HCC. While exploring the implementation of biomarker research in clinical practice to stratify tumors based on their biological aggressiveness[11], several sub-classifications of the BCLC stages consistent with prognostic factors and new scores have been proposed to improve the predictive power of this algorithm[12-14]. A more detailed stratification system based on the life expectancy may avoid offering treatments having a poor impact on patients’ prognosis and often impairing the quality of life. These considerations are extremely important with regard to the selection of patients for the clinical trials of first or second line novel systemic agents.

The present study was aimed at investigating the predictors of survival in cirrhotic patients with BCLC stage C HCC and at assessing their effect in a time dependent manner. At the preliminary survival analysis, AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL and DC were found to be independent predictors of mortality (HR = 2.194, P = 0.006 and HR = 0.190, P < 0.0001, respectively).

Hence, the first finding of our report confirms high AFP serum level as a negative predictive marker in patients with advanced HCC and its impact on survival irrespective of the tumor stage at the time of diagnosis[15-20]. Furthermore, although this category of patients is classified as “advanced stage”, we demonstrated a promising impact of the response to treatment, as shown by DC, on prognosis. Based on these findings, curative and locoregional treatments should not be “a priori” excluded in a subset of BCLC stage C patients with favorable predictive factors. As reported previously, surgical resection and LT can extend patients’ survival in the BCLC stage C also[4-6,8,9,21], which supports the need of a novel method of prediction more customized to the specific patient. The identification of 5 long-term survivors (median 63.3 mo), where 3 were included in this stage only at impaired PS (1 or 2) in absence of vascular invasion or extrahepatic tumor spread, confirms the heterogeneity of patients included in the BCLC stage C and the benefits they got in terms of DC. In four patients, locoregional treatments were feasible and two of them were subjected to LT successfully. As already reported[22], the provision based on PS used in the BCLC algorithm is questionable. Furthermore, PS scores are subjective measures with high inter-observer variability, and it is often difficult to correctly evaluate tumor-related symptoms in patients already presenting compromised general conditions. In the current study, PS has not been found to be an independent predictor of survival, and this supports the hypothesis that alone it cannot be considered as an exclusion criterion for curative treatments. Outstandingly, the majority of the patients (88.2%) in our series showed a PS 0 or 1, and therefore, only a small subgroup of patients (11.7%) fell in PS 2 class, and that may have influenced the overall survival insignificantly. However, the non-homogeneity of PS stages among BCLC C patients may be attributed to the sequential enrollment of the subjects included in the analysis rather than a selection-bias, and gives a better understanding of what happens in the real field practice.

The novel finding surfaced out from our study is the dynamic influence of AFP serum level and DC on survival period (Figure 2). In particular, the log curve of the hazard ratio for AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL elevated at high beta points implying a direct correlation with mortality, but declined steadily over time. This was more evident during the early follow-up (within 6 mo), which reached the zero point and then increased slightly afterwards, and finally became constant in the later stage. The DC beta value showed an inverse tendency, being constantly negative and increasing towards the zero point at about 6 mo of follow-up; however, it decreased significantly after the first year. At the Cox regression model including time-dependent coefficients, the most noticeable prognostic effect of AFP appeared in the early follow-up period, with 83.5% probability of mortality during the first 6 mo of follow-up of patients with AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL compared to those with a lower value (HR 5.073, 95%CI: 2.159-11.916, P = 0.0002). On the other hand, the DC was found to be defensive against death, as evident especially in the long-term follow-up (> 12 mo, HR 0.110, P < 0.0001). This type of dynamic behavior of prognostic factors has not been documented earlier during the establishment of HCC, while for other malignancies, such as breast, lung, and colorectal cancer, it has already been described. Time-dependent analysis has allowed to model patients’ survival more precisely, considering the dynamic behavior of mortality risk factors and pointing out the reverse effect of AFP serum level and DC on prognosis temporally. Our findings, therefore, emphasize that tumor biological aggressiveness remains the most important short time prognostic indicator whereas in the long term, the achievement of DC is very decisive to ameliorate patients’ survival expectancy. This further supports the efforts towards improving the therapy management and also implementing the treatment options in the BCLC algorithm for stage C patients. Nevertheless, since high AFP serum level is associated with an increased risk of early mortality, the trials assaying new systemic agents or second line therapies should be very careful in selecting the patients, and consequences should be evaluated optimally based on the stratification of the biological aggressiveness.

The second milestone of our study was to identify predictive factors of DC. The presence of macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread was found to be independently associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving DC (OR = 0.263, P = 0.002). The negative effect of tumor diffusion outside the liver or into the bloodstream on patients’ prognosis is well known, as thoroughly discussed in previous reports[23-25], and this could be indirectly due to the inadequacy of the currently available treatments to control an aggressive disease in an effective and systemic manner. Nevertheless, in our study the 61 patients showing macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread received treatment with a lower frequency as compared to those with non-invasive tumors (44/61, 72.1% vs 44/49, 89.8%, P = 0.029). Due to the extensive tumor burden, in this subgroup of patients supportive care was taken more often and this may also be the reason for the reduced DC rates to some extent.

Recently, the NIACE score has been proposed as a useful tool for the prognostic sub-staging of BCLC stage C patients, as well as for the management of treatment and for the selection of patients in clinical trials[14]. Probably, the different biological characters of tumors encompassed in our investigation could have negatively affected the prognostic ability of the NIACE score. Indeed, only 14% of the patients in the NIACE study cohort had previously undergone a treatment for HCC, as compared to 51.8% of the patients in our series, and the prevalence of alcohol related liver disease was higher than in our series of patients (30% vs 15.5%).

A possible limitation of this study could be its retrospective nature, although this was partially overcome by the rigorous and prospective collection of clinical records by the multidisciplinary group. Despite of having limited the number of records included in the analysis, the inclusion of patients treated only at our Center has reduced biasness related to diverse modalities of treatment or imaging interpretation by radiologists at different Centers.

The liver function did not appear to have a significant impact on patients’ prognosis in our analysis; probably, a high tumor-related mortality has overcome the impact of hepatic impairment on survival. However, this cannot be absolutely confirmed, as the number of patients with conserved liver function largely exceeded that of patients with more severe liver impairment (74.5% Child A vs 25.5% Child B class).

In conclusion, our data confirm that the BCLC stage C comprises a huge heterogeneous group of cirrhotic patients suitable for locoregional and potentially curative treatments. This is the first report highlighting the reverse and time-dependent effect of AFP serum level and DC as prognostic factors in cirrhotic patients with advanced stage HCC. In the patients with pre-treatment AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL the risk of early death increases up to 80%, while the achievement of post-treatment DC, which is less likely in the presence of macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic tumor spread, suggests higher chances of long-term survival. The combination of these predictive factors may be helpful in the sophistication of patients’ prognosis, thereby being valuable in the selection of patients suitable for clinical trials and in designing the therapeutic strategy.

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) includes a heterogeneous group of patients with different clinical and tumor characteristics and survival expectancy, for whom sorafenib is the only recommended treatment option. The present study investigates the outcome of BCLC C patients who underwent different locoregional, surgical or systemic treatments.

To better stratify the prognosis of patients with BCLC C stage HCC.

To characterize the prognosis of cirrhotic patients with BCLC stage C HCC as assessed by a multidisciplinary team in an Italian tertiary care center and to identify those factors predicting the achievement of disease control (DC).

The prospective database of the Hepatocatt multidisciplinary group, containing clinical, tumor and outcome data of all liver cancer subjects evaluated in the seven years at our Institute was reviewed.

The study confirms that the BCLC stage C comprises a huge heterogeneous group of cirrhotic patients suitable for locoregional and potentially curative treatments. Moreover, this is the first report highlighting the reverse and time-dependent effect of alphafetoprotein (AFP) serum level and DC as prognostic factors in cirrhotic patients with advanced stage HCC.

The novel finding surfaced out from our study is the dynamic influence of AFP serum level and DC on survival period. In particular, the AFP serum level > 200 ng/mL was significantly associated with higher risk of mortality within the first 6 mo of patients’ entry into the BCLC stage C; conversely, DC exercised a significant protective effect in long-term phase. Our report also highlight that the presence of macrovascular invasion and/or extrahepatic spread is independently associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving DC. Based on these findings, curative and locoregional treatments should not be “a priori” excluded in a subset of BCLC stage C patients. Indeed, predictive factors may be helpful in the sophistication of patients’ prognosis, thereby being valuable in the selection of patients suitable for clinical trials and in designing the therapeutic strategy.

Given the higher number of heterogeneous and complex cases encountered in the field-practice, the BCLC classification is often not exhaustive, and the increasing number of new therapeutic options and their combinations makes difficult to strictly adhere to BCLC suggestions. New algorithms for the stratification of patients’ prognosis are needed to improve clinical practice.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Makisalo H, Zhao HT S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4059] [Cited by in RCA: 4521] [Article Influence: 347.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6573] [Article Influence: 469.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10270] [Article Influence: 604.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Hernández-Guerra M, Hernández-Camba A, Turnes J, Ramos LM, Arranz L, Mera J, Crespo J, Quintero E. Application of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer therapeutic strategy and impact on survival. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:284-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Borzio M, Fornari F, De Sio I, Andriulli A, Terracciano F, Parisi G, Francica G, Salvagnini M, Marignani M, Salmi A. Adherence to American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of an Italian field practice multicenter study. Future Oncol. 2013;9:283-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Leoni S, Piscaglia F, Serio I, Terzi E, Pettinari I, Croci L, Marinelli S, Benevento F, Golfieri R, Bolondi L. Adherence to AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in clinical practice: experience of the Bologna Liver Oncology Group. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:549-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mazzaferro V, Sposito C, Bhoori S, Romito R, Chiesa C, Morosi C, Maccauro M, Marchianò A, Bongini M, Lanocita R. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for intermediate-advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase 2 study. Hepatology. 2013;57:1826-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, Takayama T, Capussotti L, Nuzzo G, Vauthey JN, Choti MA, De Santibanes E, Donadon M. A snapshot of the effective indications and results of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in tertiary referral centers: is it adherent to the EASL/AASLD recommendations?: an observational study of the HCC East-West study group. Ann Surg. 2013;257:929-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, Trevisani F, Farinati F, Spolverato G, Volk M, Giannini EG, Ciccarese F, Piscaglia F, Rapaccini GL, Di Marco M, Caturelli E, Zoli M, Borzio F, Cabibbo G, Felder M, Gasbarrini A, Sacco R, Foschi FG, Missale G, Morisco F, Svegliati Baroni G, Virdone R, Cillo U; Italian Liver Cancer (ITA. LI.CA) group. Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:617-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3353] [Cited by in RCA: 3303] [Article Influence: 220.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 11. | Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, Llovet JM. Genetic Landscape and Biomarkers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1226-1239.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 952] [Article Influence: 95.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bolondi L, Burroughs A, Dufour JF, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, Raoul JL, Sangro B. Heterogeneity of patients with intermediate (BCLC B) Hepatocellular Carcinoma: proposal for a subclassification to facilitate treatment decisions. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:348-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Farinati F, Vitale A, Spolverato G, Pawlik TM, Huo TL, Lee YH, Frigo AC, Giacomin A, Giannini EG, Ciccarese F. LI.CA study group. Development and Validation of a New Prognostic System for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Adhoute X, Pénaranda G, Raoul JL, Blanc JF, Edeline J, Conroy G, Perrier H, Pol B, Bayle O, Monnet O. Prognosis of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a new stratification of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C: results from a French multicenter study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:433-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pompili M, Rapaccini GL, Covino M, Pignataro G, Caturelli E, Siena DA, Villani MR, Cedrone A, Gasbarrini G. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with compensated cirrhosis and small hepatocellular carcinoma after percutaneous ethanol injection therapy. Cancer. 2001;92:126-135. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Farinati F, Marino D, De Giorgio M, Baldan A, Cantarini M, Cursaro C, Rapaccini G, Del Poggio P, Di Nolfo MA, Benvegnù L. Diagnostic and prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: both or neither? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:524-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khalaf N, Ying J, Mittal S, Temple S, Kanwal F, Davila J, El-Serag HB. Natural History of Untreated Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a US Cohort and the Role of Cancer Surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:273-281.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kudo M, Izumi N, Sakamoto M, Matsuyama Y, Ichida T, Nakashima O, Matsui O, Ku Y, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M; Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Survival Analysis over 28 Years of 173378 Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Japan. Liver Cancer. 2016;5:190-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Duvoux C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Decaens T, Pessione F, Badran H, Piardi T, Francoz C, Compagnon P, Vanlemmens C, Dumortier J. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including α-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:986-994.e3; quiz e14-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 55.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hameed B, Mehta N, Sapisochin G, Roberts JP, Yao FY. Alpha-fetoprotein level > 1000 ng/mL as an exclusion criterion for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma meeting the Milan criteria. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:945-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Vitale A, Morales RR, Zanus G, Farinati F, Burra P, Angeli P, Frigo AC, Del Poggio P, Rapaccini G, Di Nolfo MA. Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging and transplant survival benefit for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:654-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hsu CY, Lee YH, Hsia CY, Huang YH, Su CW, Lin HC, Lee RC, Chiou YY, Lee FY, Huo TI. Performance status in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: determinants, prognostic impact, and ability to improve the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system. Hepatology. 2013;57:112-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28:751-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 977] [Cited by in RCA: 963] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Liu PH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, Lee YH, Su CW, Huang YH, Lee FY, Lin HC, Huo TI. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: Assessment of eleven staging systems. J Hepatol. 2016;64:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ponziani FR, Bhoori S, Germini A, Bongini M, Flores M, Sposito C, Facciorusso A, Gasbarrini A, Mazzaferro V. Inducing tolerability of adverse events increases sorafenib exposure and optimizes patient’s outcome in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2016;36:1033-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |