Published online Jan 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i3.161

Peer-review started: July 18, 2016

First decision: August 4, 2016

Revised: September 3, 2016

Accepted: October 17, 2016

Article in press: October 18, 2016

Published online: January 28, 2017

Processing time: 192 Days and 1.3 Hours

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the main causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. In the last 5 years, treatment for HCV infection has experienced a marked development. In 2014, the use of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with or without concomitant weight-based ribavirin was approved with a very significant increase in the sustained virological response. However, new side effects have been associated. We report the first case of an HCV infected patient treated for 12 wk with the combination of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir plus ribavirin who developed a miliary tuberculosis (TB) infection while on therapy. The patient was a 65-year-old woman, who referred malaise, asthenia, hyporexia, 7 kg weight loss, productive cough, evening fever and night sweats, right after finishing the treatment. The chest computed tomography-scan revealed a superior mediastinal widening secondary to numerous lymphadenopathies with extensive necrosis and bilateral diffuse lung miliary pattern with little subsequent bilateral pleural effusion, highly suggestive of lymph node tuberculosis with lung miliary spread. A bronchoscopy was performed and bronchial suction showed more than 50 acid-alcohol resistant bacillus per line. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA was detected in blood by polymerase chain reaction, which confirmed the diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis. Some cases of TB infection have been identified with α-interferon-based therapy and with the triple therapy of pegylated interferon, ribavirin and boceprevir or telaprevir. However, significant infection has not been reported with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir plus ribavirin. We believe that the case is relevant to increase awareness of opportunistic infections and particularly TB infection. Although the international guidelines offer no recommendation regarding TB screening, we wonder whether it would be advisable to screen for opportunistic infections prior to the introduction of HCV therapy.

Core tip: Cases of tuberculosis (TB) infection have been identified with α-interferon-based therapy and the triple therapy with pegylated-interferon, ribavirin and boceprevir or telaprevir. This is the first case of a TB infection during treatment with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir plus ribavirin. It is relevant to increase awareness of TB due to its variety of symptoms, which can be confused with those associated to the hepatitis C virus or the antiviral treatment. Considering the impaired immune system of cirrhotic patients and that these drugs arrived slightly more than one year ago it is important to be conscious of the potential events that can be related with the treatment.

- Citation: Ballester-Ferré MP, Martínez F, Garcia-Gimeno N, Mora F, Serra MA. Miliary tuberculosis infection during hepatitis C treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir plus ribavirin. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(3): 161-166

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i3/161.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i3.161

Affecting more than 160 million people and at an increasingly higher rate, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the main causes of chronic liver disease worldwide. In the last 5 years, treatment for HCV infection has experienced a marked development, especially in the case of treatment for genotype 1. Previously, treatment was based on pegylated interferon and ribavirin for 48 wk, which achieved a sustained virological response (SVR) rate of 45% to 50%. In 2011, the first generation of protease inhibitors-telaprevir and boceprevir-reached the market. The triple therapy with peg-interferon, ribavirin and a protease inhibitor was then adopted as the standard of care, followed in 2013 by the approval of the second generation of protease inhibitor, simeprevir, and the polymerase inhibitor, sofosbuvir. In 2014, the use of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir was approved, as well as the use of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir for the treatment of HCV genotype 1 infections with or without concomitant weight-based ribavirin. These changes have brought a very significant increase in the SVR, with rates rising above 90%. However, new side effects, such as decompensation of cirrhosis, liver toxicity and some infections, have been associated[1].

We report the first case of an HCV-infected patient treated for 12 wk with the combination of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir plus ribavirin who developed a miliary tuberculosis infection while on therapy.

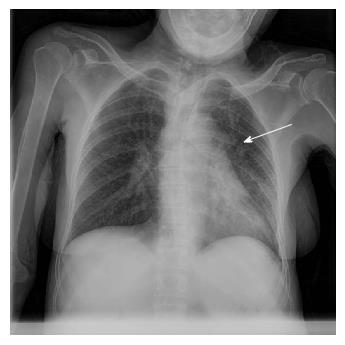

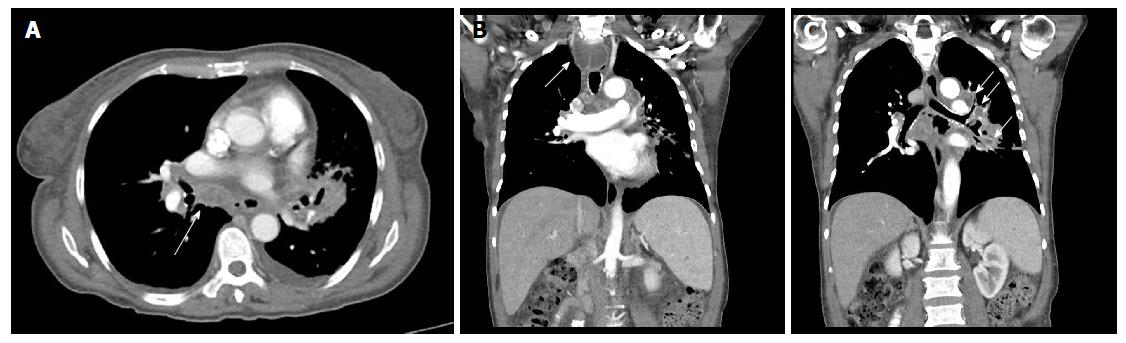

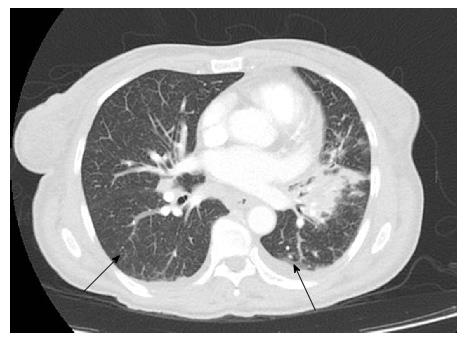

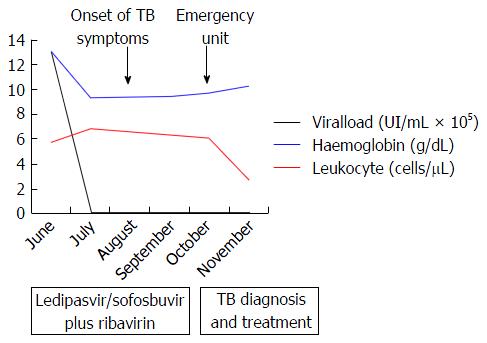

The patient was a 65-year-old woman from Equatorial Guinea, who had been residing in Spain since 2000 (16 years), without any recent trip reported. Her medical history included a blood transfusion event in 1996, diabetes mellitus type 2 diagnosed in 1997 under treatment with insulin, no current nor previous smoking habits and no underlying pulmonary disease or symptoms. In 2000 the patient was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain. On physical examination hepatomegaly was detected. The blood test revealed hypertransaminasemia and the serology test permitted the diagnosis of chronic HCV infection. HCV genotype was 1a and viral load was 720000 IU/mL. An abdominal ultrasonography revealed a discrete homogeneous hepatomegaly with no focal liver lesions and a transient elastography resulted in 7.9 kPa. A liver biopsy was performed showing chronic HCV infection with Batts and Ludwig[2] stage 1, grade 1. In January, 2008, the patient was treated with the standard at that time, based on the combination of peg-interferon-α 2a (180 μg/wk) with ribavirin (1200 mg/d) during 12 mo. Unfortunately, treatment had to be stopped three mo after starting due to the appearance of side effects: Gluteus abscess, leucopenia and anemia. The patient was followed up in outpatients’ clinic without further therapy for hepatitis C until 2015 when she was evaluated for starting treatment with the new direct antiviral agents (DAAs). She was asymptomatic and there were no signs of ascites, edema, bleeding or encephalopathy nor lymphadenopathies on physical examination. Body weight was 54 kg. Hemoglobin level was 12.9 g/dL (reference range -RR-: 11.5-15.5), leucocyte count 5.56 cells/μL (RR: 3.9-11), absolute neutrophil count 1.14 cells/μL (RR: 2.5-7.5), absolute lymphocyte count 2.46 cells/μL (RR: 1.5-4.5) and platelet count 144.000 cells/µL (RR: 160.000-400.000). Albumin was 4 g/dL (RR: 3.5-5.2), total bilirubin 0.43 mg/dL (RR: 0.10-1.00), INR was 1.09 (RR: 0.85-1.35), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 126 U/L (RR: 1-31), aspartate aminotransferase 120 U/L (RR: 1-31), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase 52 U/L (RR: 1-38) and alkaline phosphatase 90 U/L (RR: 30-120). Alpha-fetoprotein was 9.3 ng/mL (RR: 0.0-7.0) and glycosylated-hemoglobine was 5.2% (RR: 4.0-6.1). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology was negative. Viral load was 1300000 IU/mL and HCV genotype was 1a and the IL28B gene was TC. An abdominal ultrasound exam revealed signs of hypertrophy of the left and caudate liver segments with a focal benign lesion (hemangioma) of 9 mm in segment IV with no changes when compared to previous tests, normal portal vein caliber with hepatopetal flow and a splenomegaly of 13 cm. Transient elastography scored a result of 11.1 kPa. Treatment with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir plus ribavirin during 12 wk was initiated in June, 2015. The check-up at the clinic one month later showed no symptoms or pathological signs on physical examination. The treatment was completed but in September, 2015, the patient complained about malaise, asthenia, hyporexia, 7 kg weight loss and dry cough. She referred that these symptoms had appeared one month before she was attended at the emergency unit. However, due to the clinical and hemodynamic stability, the patient was discharged with further outpatient control. In the next 2 wk, in early October, a more productive cough with white sputum, evening fever and night sweats were added to the previous symptoms and upon examination at the emergency unit again, the patient’s temperature was 39 °C, blood pressure was 131/94 mmHg, heart rate was 130 bpm with 98% oxygen saturation. She was conscious with no signs of neurologic impairment. Cardiac and pulmonary auscultation were normal, the abdomen was soft with a 3 cm hepatomegaly and a 2 cm splenomegaly without signs of ascites or abdominal pain, limbs showed no signs of edema and no cervical, axillary or inguinal adenopathies were found. The blood test highlighted a sodium level of 129 mmol/L (RR: 135-145), ALT 38 U/L, CRP 94 mg/L (RR: < 5), hemoglobin level 9.6 g/dL, leucocyte count 5.98 cells/μL, absolute neutrophil count 4.84 cells/μL, absolute lymphocyte count 0.78 cells/μL, platelet count 114000 cells/μL and INR 1.26 with the rest of parameters standing within the normal range. The arterial gasometry showed pH 7.51 (RR: 7.35-7.45), pO2 126 mmHg (RR: 83-108), pCO2 29 mmHg (RR: 35-45), lactate 1.6 mmol/L (RR: 0.6-1.17) and bicarbonate 25 mEq/L (RR: 20-29). The urine test, abdominal X-ray and cranial computed tomography (CT) scan that were carried out revealed no abnormalities. The chest X-ray showed a left hilar widening (Figure 1) and the patient was admitted to the hospital for further studies. The blood culture was negative, as well as the malaria and leishmania tests. The sputum direct vision showed mixed microbiota with predominance of gram-negative bacillus with no acid-alcohol resistant bacillus (AARB) seen. Nevertheless, Mycobacterium tuberculosis showed up in the culture of the sputum after 10 d. Chest and abdomen CT scan revealed a superior mediastinal widening secondary to numerous lymphadenopathies with extensive necrosis, causing a displacement of the esophagus and trachea, and contiguous to these lymphadenopathies, a left hilar mass displaying an air bubble communicated with the left bronchial three (Figure 2), as well as a bilateral diffuse lung miliary pattern with little subsequent bilateral pleural effusion (Figure 3). These findings were highly suggestive of lymph node tuberculosis with lung miliary spread, being less likely to be attributed to a malignant left hilar mass. A flexible bronchoscopy was performed showing a bossing in the upper part of the trachea and mucosa thickening in both main bronchi with partial stenosis of the left upper lobule bronchi. The retrotracheal mass was biopsied, displaying acute inflammation in the pathological study with negative Zielh Neelsen test. However, in the bronchial suction there were more than 50 AARB per line. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA was detected in blood by RCP which confirmed the diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis. The first line treatment for tuberculosis with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol was initiated, presenting remission of the symptoms and a good tolerance with no signs of liver toxicity (Figure 4).

Tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a worldwide health problem, remaining as the leading cause of death from infectious diseases. It is estimated that 30% of the global population hosts TB in its latent form, which can be reactivated with the presence of several factors, such as aging, smoking, alcohol use, diabetes, chronic renal failure, cancer, a weakened immune system, glucocorticoids or tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors use. Furthermore, miliary tuberculosis form, has only been described in immunocompromised hosts, especially in patients with underlying T-cell deficiencies such as HIV infection. The classic presenting symptoms of pulmonary TB include persistent fever, weight loss, drenching night sweats, persistent cough (often with sputum production), and hemoptysis; whilst extra-pulmonary TB can affect any organ with a wide variety of symptoms, and therefore requires a high index of clinical suspicion. Without treatment, TB has a mortality rate of 50% within 5 years. Various cell types and cytokines are crucial: T cells (CD4+, CD8+, and natural killer) and macrophages participate in protection against TB, and interferon-α and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are essential cytokines for the control of acute TB infection[3].

Two conditions might have contributed to the TB infection. On one hand, cirrhosis by itself is associated with lymphocyte and macrophage dysfunction and decreased production of interferon-α and TNF-α and it may be linked to a higher TB risk. A Taiwan study, showed that active TB incidence rates were significantly higher among cirrhotic patients compared with noncirrhotic patients, particularly those with alcoholism and HCV infection[4].

On the other hand, TB infection has been reported anecdotically in patients with HCV infection undergoing α-interferon-based therapy, usually as a reactivation of latent cases. As an example, 18 cases of TB were observed in patients under HCV treatment in Brazil[5]. Many studies have already shown that α-interferon inhibits type 1 immune response, which is characterized by IL-2, interferon-α and TNF-α production, cytokines that restrain Mycobacterium tuberculosis. On the contrary, ribavirin is a guanosine analogue that has demonstrated to have an immunomodulatory effect, shifting a type 2 response to a type 1 in plaque-forming cells in vivo. When human T-lymphocytes are activated, ribavirin enhances a type 1 cytokine response producing increased levels of IL-2, interferon-α and TNF-α while suppressing the type 2 response with IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10[6]. Therefore, ribavirin stimulates the host adaptive immune response responsible for protection against TB infection and it may act as a protective factor; however, no studies have been specifically performed to prove it. Some other cases of TB infection have also been reported with the triple therapy of pegylated interferon, ribavirin and boceprevir or telaprevir, the first generation of protease inhibitors[1]. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir are both DAAs. Sofosbuvir works as an inhibitor of the HCV NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Ledipasvir is an NS5A inhibitor and its exact mechanism of action is unknown, but one suggested mechanism is its inhibition of hyperphosphorylation of NS5A, which seems to be required for viral production. Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir phase III studies for HCV infection treatment showed that the most common adverse events reported by patients were fatigue, headache and nausea[7]. Addition of ribavirin to ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for HCV therapy for patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis was associated with a greater incidence of common adverse effects, concomitant medication use and laboratory abnormalities such as anemia, increased levels of total bilirubin and lymphopenia; but rates of severe side effects and interruptions of treatment resulted similar, and no increased infection episodes were detected despite the reported decrease in lymphocytes[8]. In order to reduce the side effects of these drugs, advanced technologies are used during their development such as computer-aided leading drug optimization[9].

Indeed, significant infection has not been reported with the new era of free-interferon regiment treatment. This case is, to the best of our knowledge, the first case report of a miliary TB infection during HCV infection treatment with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir plus ribavirin. Although the association with the DAAs has not been proven and it may be a coincidence that the two infections have occurred in a close time frame, several data should make clinicians wonder: The patient had diabetes and chronic liver disease as a risk factors for TB, nevertheless both were well controlled; she was asymptomatic and with no signs on physical examination neither before starting the treatment nor after one month of the beginning, which goes against the hypothesis that she may have reactivated TB prior to therapy and it has just presented late; moreover, the mechanisms underlying these drugs effects are currently unknown and further immunological studies should be performed in order to find out how the innate and adaptive immune responses are altered by the different treatment regimens[10].

We believe that the case we have reported is relevant to increase awareness of opportunistic infections, particularly TB infection due to its variety of symptoms which can be confused with those associated to the HCV infection or the antiviral treatment and the high mortality rate of TB infection without treatment. Considering the impaired immune system of cirrhotic patients and the fact that these DAAs arrived on the market slightly more than one year ago and no long-term side effects have been described, we consider that it is important to be conscious of the potential events that can be related with the HCV treatment. In addition, although the international guidelines for the management of HCV infection[11,12] offer no recommendation regarding TB screening, we wonder whether it would be advisable to screen for opportunistic infections, via tuberculin skin test and/or interferon gamma releasing assays, prior to the introduction of HCV therapy.

A 65-year-old woman with history of diabetes mellitus type 2, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and no current nor previous smoking habits and no underlying pulmonary disease or symptoms.

The patient presented with malaise, asthenia, hyporexia, 7 kg weight loss, productive cough with white sputum, evening fever and night sweats right after finishing the HCV treatment with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir plus ribavirin for 12 wk.

Respiratory infection, side effects of HCV treatment.

The blood test highlighted a sodium level of 129 mmol/L (RR: 135-145), ALT 38 U/L, CRP 94 mg/L (RR: < 5), hemoglobin level 9.6 g/dL, leucocyte count 5.98 cells/μL, absolute neutrophil count 4.84 cells/μL, absolute lymphocyte count 0.78 cells/μL, platelet count 114000 cells/μL and INR 1.26 with the rest of parameters standing within the normal range. The arterial gasometry showed pH 7.51 (RR: 7.35-7.45), pO2 126 mmHg (RR: 83-108), pCO2 29 mmHg (RR: 35-45), lactate 1.6 mmol/L (RR: 0.6-1.17) and bicarbonate 25 mEq/L (RR: 20-29).

The chest X-ray showed a left hilar widening. The chest computed tomography scan revealed a superior mediastinal widening secondary to numerous lymphadenopathies with extensive necrosis, causing a displacement of the esophagus and trachea, and contiguous to these lymphadenopathies, a left hilar mass displaying an air bubble communicated with the left bronchial three, as well as a bilateral diffuse lung miliary pattern with little subsequent bilateral pleural effusion.

The first line treatment for tuberculosis with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol.

Cases of tuberculosis infection have been identified with α-interferon-based therapy and the triple therapy with pegylated-interferon, ribavirin and boceprevir or telaprevir.

This is the first case of a TB infection during treatment with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir plus ribavirin.

The manuscript is reasonably well written and is thought to have useful information for readers.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kawakami Y, Ma DL, Omran D, Vasudevan A S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Rodríguez-Martín L, Linares Torres P, Aparicio Cabezudo M, Fernández-Fernández N, Jorquera Plaza F, Olcoz Goñi JL, Gutiérrez Gutiérrez E, Fernández Morán EM. [Reactivation of pulmonary tuberculosis during treatment with triple therapy for hepatitis C]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:273-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Batts JP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis. An uptodate on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1409-1417. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Zumla A, Raviglione M, Hafner R, von Reyn CF. Tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:745-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin YT, Wu PH, Lin CY, Lin MY, Chuang HY, Huang JF, Yu ML, Chuang WL. Cirrhosis as a risk factor for tuberculosis infection--a nationwide longitudinal study in Taiwan. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:103-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Oliveira Uehara SN, Emori CT, Perez RM, Mendes-Correa MC, de Souza Paiva Ferreira A, de Castro Amaral Feldner AC, Silva AE, Filho RJ, de Souza E Silva IS, Ferraz ML. High incidence of tuberculosis in patients treated for hepatitis C chronic infection. Braz J Infect Dis. 2016;20:205-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Te HS, Randall G, Jensen DM. Mechanism of action of ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2007;3:218-225. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, Nahass R, Ghalib R, Gitlin N, Herring R. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1065] [Cited by in RCA: 1064] [Article Influence: 96.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Alqahtani SA, Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Gordon SC, Mangia A, Kwo P, Fried M, Yang JC, Ding X, Pang PS. Safety and tolerability of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with and without ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection: Analysis of phase III ION trials. Hepatology. 2015;62:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Meng XY, Zhang HX, Mezei M, Cui M. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2011;7:146-157. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Rehermann B, Bertoletti A. Immunological aspects of antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. Hepatology. 2015;61:712-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2015. J Hepatol. 2015;63:199-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 877] [Cited by in RCA: 910] [Article Influence: 91.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62:932-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 912] [Cited by in RCA: 992] [Article Influence: 99.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |