Published online Jan 28, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i3.147

Peer-review started: September 20, 2016

First decision: October 21, 2016

Revised: November 9, 2016

Accepted: November 27, 2016

Article in press: November 29, 2016

Published online: January 28, 2017

Processing time: 127 Days and 7.9 Hours

To identify independent risk factors for biliary complications in a center with three decades of experience in liver transplantation.

A total of 1607 consecutive liver transplantations were analyzed in a retrospective study. Detailed subset analysis was performed in 417 patients, which have been transplanted since the introduction of Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)-based liver allocation. Risk factors for the onset of anastomotic biliary complications were identified with multivariable binary logistic regression analyses. The identified risk factors in regression analyses were compiled into a prognostic model. The applicability was evaluated with receiver operating characteristic curve analyses. Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier analyses with the log rank test were applied where appropriate.

Biliary complications were observed in 227 cases (14.1%). Four hundred and seventeen (26%) transplantations were performed after the introduction of MELD-based donor organ allocation. Since then, 21% (n = 89) of the patients suffered from biliary complications, which are further categorized into anastomotic bile leaks [46% (n = 41)], anastomotic strictures [25% (n = 22)], cholangitis [8% (n = 7)] and non-anastomotic strictures [3% (n = 3)]. The remaining 18% (n = 16) were not further classified. After adjustment for all univariably significant variables, the recipient MELD-score at transplantation (P = 0.006; OR = 1.035; 95%CI: 1.010-1.060), the development of hepatic artery thrombosis post-operatively (P = 0.019; OR = 3.543; 95%CI: 1.233-10.178), as well as the donor creatinine prior to explantation (P = 0.010; OR = 1.003; 95%CI: 1.001-1.006) were revealed as independent risk factors for biliary complications. The compilation of these identified risk factors into a prognostic model was shown to have good prognostic abilities in the investigated cohort with an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.702.

The parallel occurrence of high recipient MELD and impaired donor kidney function should be avoided. Risk is especially increased when post-transplant hepatic artery thrombosis occurs.

Core tip: This retrospective study investigates the occurrence of biliary complications in a total of 1607 consecutive liver transplant patients throughout three decades. Since introduction of Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)-based liver allocation, the recipient’s MELD-score at transplantation, the development of hepatic artery thrombosis post-operatively, as well as the donor creatinine prior to explantation were identified as independent risk factors, thus a combination of high recipient MELD-score and impaired donor kidney function should be avoided. Risk is especially increased when post-transplant hepatic artery thrombosis occurs. A prognostic model for the prediction of anastomotic biliary complications was developed and successfully internally validated.

- Citation: Kaltenborn A, Gutcke A, Gwiasda J, Klempnauer J, Schrem H. Biliary complications following liver transplantation: Single-center experience over three decades and recent risk factors. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(3): 147-154

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i3/147.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i3.147

Since its introduction as standard procedure in 1983, liver transplantation is nowadays widely accepted as the only live-saving treatment for end stage liver diseases. Nevertheless, several serious complications still endanger successful short- and long-term outcome. Biliary complications appear to be one of the most common issues during follow-up[1]. Diverse studies reveal their notable association with mortality and an overall incidence of 10%-40% is described[2]. Moreover, the socio-economic implications due to prolonged morbidity are of increasing relevance and represent a serious burden to health care systems[3].

As the bile duct is supplied only arterially without the benefit of portal vein nourishment, there is a predetermined breaking point to cause repercussions[4]. Furthermore, donor parameters, surgical aspects as well as the recipients’ condition prior to transplant seem to affect the outcome[2]. In general, anastomotic lesions are distinguished from non-anastomotic stenosis or leakage[5]. The most common manifestations of biliary complications are strictures of the bile duct[5]. Anastomotic lesions are usually due to mechanical and surgical issues which alter the bile duct’s arterial support and occur mainly within the first 90 d after transplantation, whereas non-anastomotic lesions show a predominantly manifestation period of about six to nine month after transplant[5]. Under the term of non-anastomotic lesions systemic complications such as post-thrombotic, inflammatory and immunological processes as well as the presence of cytotoxic hydrophobic bile salts are summarized, which all lead to damage of the biliary epithelium[6].

In recent studies, inadequate surgical technique, arterial complications such as hepatic artery thrombosis, as well as donor age and macrovesicular graft steatosis could be identified as relevant risk factors for the occurrence of biliary complications in risk-adjusted multivariate analyses[5,7,8].

This study has two aims. Firstly, a historical overview over three decades of biliary complications after liver transplantation should show the development of their incidence. Secondly, main focus was to identify independent risk factors in the most recent years, which contribute to the development of early biliary complications, occurring during the direct hospital stay after liver transplantation.

In this single-center, retrospective, observational study, the influence of pre-, inter- and post-transplant aspects as relevant risk factors for the occurrence of early biliary complications, which occur during the direct hospital stay after liver transplantation, were investigated.

During follow-up patients were routinely seen in the transplant outpatient clinic at least once per year and follow-up visits consisted of physical examination, blood chemistry, as well as standardized abdominal ultrasound. Mean follow-up was 9.4 years (SD: 7.5 years). Included were all consecutive adult liver transplantations (pediatric was defined as younger than 18 years of age). Excluded from analysis were combined transplantations, split liver transplantations, and patients with re-transplantation during initial hospital stay. Since donation after cardiac death is not allowed in Germany by current law, there are no such transplantations included in this study.

In this study, the three decades of liver transplantation were divided into four eras. Era 1 reaches from 01.01.1983-31.12.1991, Era 2 from 01.01.1992-31.12.1999. Era 3 (Child-Pugh) includes the years 2000-2006 until the Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) allocation (Era 4) started in 2006.

Onset of biliary complications during the post-transplant hospital stay is defined as primary study endpoint. In the MELD-era, a more detailed analysis was performed. The further respective study endpoints are complications occurring at the bile duct anastomosis, defined as anastomotic biliary leak or stricture.

For the detection of early biliary complications after liver transplantation, daily ultrasound/Doppler investigations, daily laboratory works, and daily clinical rounds were applied. It is standard operating procedure to implant abdominal drainages during the transplant procedure, which are regularly pulled after the secretion is less than 100 mL post-transplant. The biliary anastomosis was usually performed as end- to end-anastomosis between donor common bile duct and recipient common hepatic duct using a 6/0 prolene suture in continuous manner. University of Wisconsin preservation solution was routinely used until recently, the application of HTK solution increased since its introduction in the early 1990s and is nowadays the mostly applied preservation solution. A more detailed analysis of preservation solutions and their application at the study center is given elsewhere[10]. Due to certain indications for liver transplantation, such as primary biliary diseases, a hepaticojejunostomy in Roux-Y-technique is implemented[11]. The implantation of T-tube was omitted as standard procedure at our center around 2004 and has not been applied since.

There are various therapy options for biliary complications. Early biliary complications, such as biliary leaks can be managed via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with stent implantation, whereas late complications, such as biliary stenosis or a diffuse leakage often require a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, surgical revision with a Y-Roux hepaticojejunostomy or at last resort a re-transplantation.

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Hannover Medical School (application number 1683-2013).

Risk factors for the onset of study endpoints after liver transplantation were identified with univariable and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses. The alpha-level for inclusion into multivariate modeling was set at 0.05. All variables which were significant in univariable binary logistic regression analysis were considered for the multivariable binary regression model. Variables which were included in the multivariable regression model were compiled as the prognostic score for the prediction of anastomotic biliary complications. The clinical usefulness of this score was assessed with receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Areas under the receiver operating curve (AUROCs) larger than 0.700 indicate a clinically useful prognostic model[9]. For internal validation of the developed score, randomized backwards bootstrapping was applied. Kaplan-Meier analysis with the Log-Rank test was applied were appropriate. For all statistical tests a P-value < 0.05 was defined as significant. The SPSS statistics software version 21.0 (IBM, Somers, NY, United States) was used to perform statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics of the investigated study population of 1607 consecutive liver transplants is summarized in Tables 1-3. During 30 years of follow-up, 561 (35.1%) patients deceased. The documented causes of death are summarized in Table 4.

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | n (% of cohort) |

| MELD | 21 (11.5) | 18 (6-40) | |

| BMI | 24.2 (4.5) | 24.7 (15.1-40) | |

| Days on the waiting list | 277 (41.5) | 143 (0-4299) | |

| Male: Female | 915 (57%) to 692 (43%) | ||

| Age | 46.1 (12) | 47.5 (18-73.6) | |

| ICU stay in days | 23 (33) | 9 (1-276) | |

| Pre-transplant PVT | 143 (9) | ||

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 121 (92) | 86 (38-707) | |

| Bilirubine (μmol/L) | 177 (209) | 72 (7-930) | |

| Indication HCC | 244 (15) | ||

| Indication PSC | 153 (9.5) | ||

| Indication ALF | 137 (8.5) | ||

| Indication HCV cirrh. | 101 (6.3) | ||

| Indication alc. cirrh. | 104 (6.4) | ||

| Indication biliary dis. | 326 (20.3) | ||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | n (% of cohort) |

| Gender mismatch | 929 (58) | ||

| Cold ischemic time (min) | 6.9 (220) | 593 (152-1696) | |

| Era 1 of transplantation | 303 (19) | ||

| Era 2 of transplantation | 434 (27) | ||

| Era 3 of transplantation | 453 (28) | ||

| Era 4 of transplantation | 417 (26) | ||

| > 1 arterial anastom. | 71 (4.5) | ||

| Aortal anastomosis | 164 (10.8) | ||

| Portal vein interpos. Graft | 14 (0.8) | ||

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 353 (22.4) | ||

| Post-transplant HAT | 59 (3.7) |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | n (% of cohort) |

| Age | 42 (16.9) | 43 (15-88) | |

| Male: Female | 969 (60%) to 624 (40%) | ||

| BMI | 24.8 (16.6) | 24 (20-44) | |

| Pre-transplant ICU stay | 8.7 (19.7) | 6 (1-383) | |

| Body temperature °C | 36.4 (1.0) | 36 (33-39) | |

| Bilirubine (μmol/L) | 12.5 (11.7) | 9.9 (0.9-154) | |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 96 (79) | 80 (12-885) | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 127 (108) | 114 (0.1-818) | |

| ALT (u/L) | 48 (190) | 22 (0-1136) | |

| AST (u/L) | 59 (2.67) | 29 (0-1074) | |

| GGT (u/L) | 51.2 (78.6) | 24 (0-912) | |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 7.2 (8.4) | 5.2 (0.2-103) | |

| CMV positivity | 805 (50) | ||

| Cause of death | No. of patients (% of cohort) |

| Sepsis | 109 (6.8) |

| Tumor recurrence | 103 (6.4) |

| De novo malignancy | 33 (2.1) |

| Pneumonia | 31 (1.9) |

| Liver graft: Biliary complications | 20 (1.3) |

| Cardiovascular event | 18 (1.1) |

| Liver graft: Chronic rejection | 15 (0.9) |

| Cerebral ischemia | 12 (0.8) |

| Cerebral bleeding | 11 (0.7) |

| Liver graft: HCV reinfection | 11 (0.7) |

| Cerebral edema | 9 (0.6%) |

| Liver graft: HBV reinfection | 9 (0.6) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 7 (0.4) |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 6 (0.4) |

| Liver graft: Venous thrombosis | 6 (0.4) |

| Lung: Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 4 (0.3) |

| Polytrauma | 4 (0.3) |

| Cerebral infection | 3 (0.3) |

| Liver graft: HCV de novo infection | 3 (0.3) |

| Liver graft: Initial non function | 3 (0.3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 6 (0.4) |

| Gastrointestinal ischemia | 2 (0.1) |

| Liver graft: Arterial thrombosis | 2 (0.1) |

| Suicide | 2 (0.1) |

| Liver graft: Portal vein thrombosis | 1 (0.1) |

| Non-compliance to immunosuppression | 1 (0.1) |

| Recurrent alcoholism | 1 (0.1) |

| Unknown | 129 (8.1) |

| Total | 561 (35.1) |

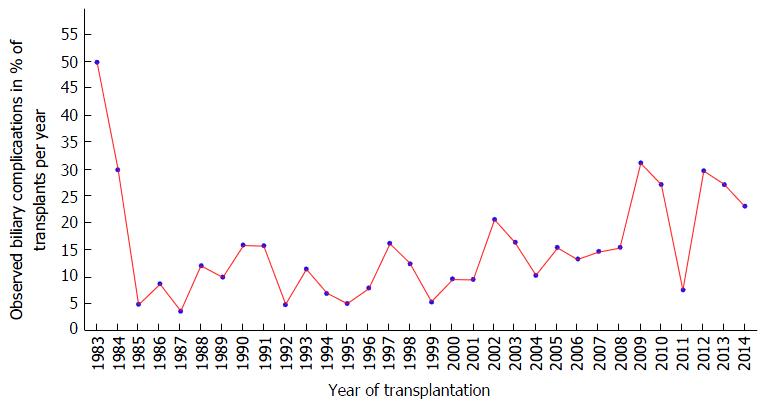

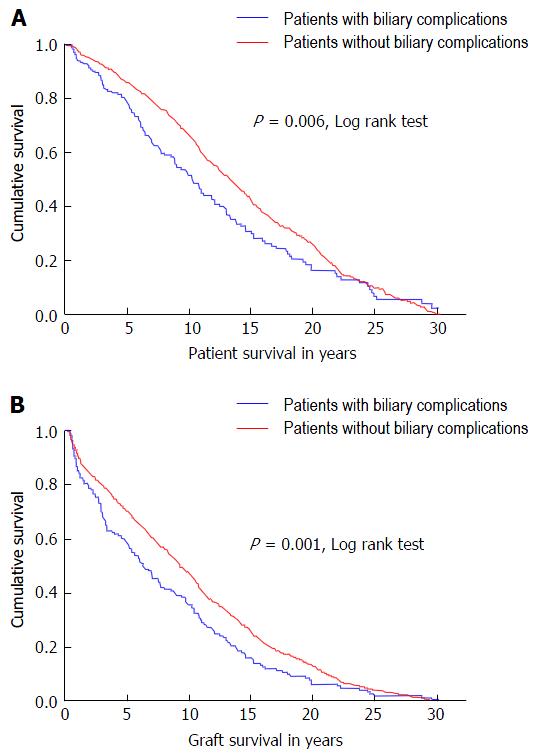

During 30 years of liver transplantation at a single center, biliary complications were observed in 227 cases (14.1%). The development of biliary complication incidence since 1983 is shown in Figure 1. Patient as well as graft survival were significantly associated to the occurrence of biliary complications during 30 years of follow-up, as shown in Kaplan Meier analysis (Figure 2).

Of the 1607 included transplantations, 417 (26%) were performed after introduction of MELD-based donor organ allocation in December 2006. During this MELD-era, 21% of patients (n = 89) suffered from early biliary complications during the initial post-transplant hospital stay. The distribution of complication type in the MELD-era is shown in Figure 3. In 46% (n = 41) of the patients an anastomotic bile leak occurred, whereas 25% (n = 22) showed an anastomotic stricture. Cholangitis occurred in 8% (n = 7), non-anastomotic strictures in 3% (n = 3) of the cases. The remaining 18% (n = 16) were not further classified.

Since the biliary anastomosis can be influenced the most by the operating surgeon, risk factors were evaluated for anastomotic biliary complications, which included biliary strictures and anastomotic leakage. In 63 patients (15.1%) anastomotic complications were observed. Table 5 shows the results of univariable and multivariable binary regression analysis for identification of significant, independent risk factors for the development of anastomotic biliary complications during the initial post-transplant hospital stay. After adjustment for all univariably significant variables, the recipient MELD-score at transplantation (P = 0.006; OR = 1.035; 95%CI: 1.010-1.060), the development of HAT post-operatively (P = 0.019; OR = 3.543; 95%CI: 1.233-10.178), as well as the donor creatinine prior to explantation (P = 0.010; OR = 1.003; 95%CI: 1.001-1.006) were revealed as independent risk factors.

| Variable | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

| P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | ||

| Recipient data | MELD | 0.029 | 1.036 (1.003-1.050) | 0.006 | 1.035 (1.010-1.060) |

| BMI | 0.438 | ||||

| Days on the waiting list | 0.594 | ||||

| Gender | 0.494 | ||||

| Age | 0.752 | ||||

| ICU stay in days | 0.025 | 1.018 (1.001-1.012) | 0.093 | ||

| Pre-transplant PVT | 0.056 | ||||

| Creatinine | 0.042 | 1.003 (1.001-1.005) | |||

| Bilirubine | 0.034 | 1.001 (1.001-1.002) | |||

| Indication HCC | 0.328 | ||||

| Indication PSC | 0.415 | ||||

| Indication ALF | 0.620 | ||||

| Indication HCV cirrh. | 0.685 | ||||

| Indication alc. cirrh. | 0.769 | ||||

| Indication biliary dis. | 0.115 | ||||

| Transplant-specific data | Gender mismatch | 0.620 | |||

| Cold ischemic time | 0.417 | ||||

| Era of transplantation | 0.124 | ||||

| Preservation solution | 0.746 | ||||

| > 1 arterial anastom. | 0.396 | ||||

| Aortal anastomosis | 0.331 | ||||

| Portal vein interpos. Graft | 0.251 | ||||

| Hepaticojejunostomy | 0.425 | ||||

| Post-transplant HAT | 0.048 | 2.999 (1.010-8.056) | 0.019 | 3.543 (1.283-10.178) | |

| Operative duration | 0.624 | ||||

| Donor-specific data | Age | 0.738 | |||

| Gender male | 0.003 | 1.835 (1.050-3.303) | 0.066 | ||

| BMI | 0.014 | 0.923 (0.861-0.990) | 0.056 | ||

| Pre-transplant ICU stay | 0.115 | ||||

| Body temperature | 0.921 | ||||

| Bilirubine | 0.022 | 1.027 (1.005-1.050) | 0.073 | ||

| Creatinine | 0.020 | 1.003 (1.001-1.005) | 0.010 | 1.003 (1.001-1.006) | |

| CRP | 0.406 | ||||

| ALT | 0.765 | ||||

| AST | 0.613 | ||||

| GGT | 0.278 | ||||

| Urea | 0.581 | ||||

| CMV positivity | 0.100 | ||||

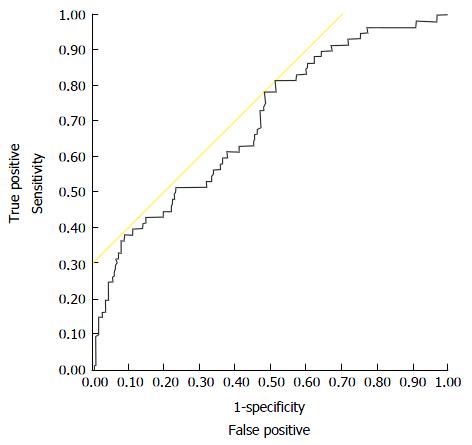

Compiling all variables which were included in multivariable analysis [recipient MELD-score, post-operative HAT, donor creatinine, donor body mass index (BMI), recipient intensive care unit (ICU) stay in days, donor gender, donor bilirubin] in a regression equation, this model provides good prognostic abilities in the investigated cohort with an AUROC of 0.702 (Figure 4). The model was internally validated applying a backwards randomized bootstrap analysis in 100 cases [mean AUROC: 0.720 (SD: 0.040)]. The proposed prognostic model is: y = 1.030 × MELD at transplantation + 0.937 × donor BMI + 1.021 × donor bilirubin + 1.003 × donor creatinine + 1.005 × posttransplant ICU days + 3.117 × posttransplant HAT + 1.741 × male donor gender.

Biliary complications are a common post-operative issue after liver transplantation. Liver transplantation has been established in the 1980s as the only life-saving standard treatment for many conditions leading to end-stage liver disease. Therefore, the number of performed liver transplantations has been increasing ever since. Biliary complications endanger early as well as long-term success of liver transplantation and are thus constantly in focus of research to improve care for transplant recipients. However, evidence from large single-center databases on the long-term follow-up of liver transplant recipients including risk-adjusted identification of probable risk factors for the development of biliary complications is still scarce. In the current study, a large European center reports its results regarding biliary complications overlooking over three decades of transplant experience. Moreover, in the recent era with the introduction of MELD-based organ allocation in late 2006 as defined starting point, relevant independent risk factors were investigated.

It could be shown that the onset of post-transplant biliary complications endangers patient as well as graft survival even in the long run (Figure 2; P = 0.006; P = 0.001, resp.). This also has serious implications for healthcare economy. A recent analysis of a large dataset with more than 12800 liver transplantations could show that biliary complications in recipients receiving a graft after brain death donation were responsible for an increment of cost of nearly 55000$ in the first post-transplant year[3]. These findings could be confirmed in the following post-transplant years as well as in donation after cardiac death transplantations.

As shown in Figure 1, the number of patients suffering from biliary complications after liver transplantation decreased very early in the observed series to a minimum of closely over 5% in 1985. This early drop might well be a result of the early surgical learning curve. It can also be assumed that some biliary complications might not be detected in these years due to technically less developed diagnostic capabilities, such as computed tomography or ultrasound. Furthermore, early mortality was comparatively high and recipients might have died before developing detectable/treatable biliary complications.

In the years between 1985 and 2006, the incidence of biliary complications was ranging from 5% to 25% of performed transplantations per year, which is comparable to other reported data[3,5,6]. These years were characterized by introduction of the Child-Pugh score-based center allocation scheme in the year 2000, which represents a paradigm shift and is therefore regarded in the analysis as a new era. After introduction of MELD-based organ allocation in late 2006, the rate of biliary complications starts to fluctuate in a wider range from 10% to as high as 30%. The notion that donor organ quality might have decreased as well as the general condition of the transplant recipients since the start of this recent era has led to a controversial discussion in the German transplant community about the usefulness of this current allocation policy.

As early as 2009, Weismüller et al[12] reported of decreased short-term survival since the introduction of MELD-based liver allocation. An association with longer surgery duration and higher recipient morbidity could be revealed as possible underlying causes. As another example, it was reported recently that indications with high chances for successful long-term survival after liver transplantation such as primary sclerosing cholangitis did not show any improved outcome since MELD-introduction in Germany and that there is relevant outcome stagnation for this entity[13].

Therefore, a more detailed analysis was applied on the MELD-era data, in which a categorization of the biliary complication into different subtypes was possible due to consequent and clear documentation, as well as electronic patient files. Since the biliary anastomosis seems to be the most susceptible part for surgical improvement measures, the anastomotic complications are in a special focus of this investigation. Multivariable, risk-adjusted analysis revealed that the MELD-score at transplantation, the donor creatinine at time of graft donation and the development of HAT after transplantation were statistically significant, independent risk factors for the onset of anastomotic biliary complications. The association of post-transplant HAT and the development of biliary complications has been observed several times and can be explained by an anatomical circumstance. The biliary tract tissue is especially vulnerable to impaired arterial vascular supply. Whereas the liver parenchyma is nourished via a dual vascular supply via portal vein and hepatic artery, the bile ducts are supplied only arterially[5]. Therefore, the biliary epithelium is more susceptible to decreased perfusion than hepatocytes, which is the case in ischemic injury and severe hypotension, both occurring in the donor organ during transplantation and after HAT.

The finding that the recipient MELD score has influence on the onset of post-transplant biliary complications seems not to be surprising. The MELD-score was shown to accurately depict the recipients state of morbidity prior to transplantation[14,15], thus identifying patients with a risk profile to have impaired healing capabilities at the bile duct anastomosis. This is further confirmed by the finding that impaired donor kidney function as depicted via increased donor creatinine levels contributes to the development of anastomotic bile duct lesions, since this further intensifies the unfavorable metabolic situation at the anastomosis, which is at risk for ischemic injury.

After a relevant drop of the incidence of biliary complications in 2011, the number of observed complications increased again in 2012. The data does not clearly provide insights into the root-causes of this observed development, thus, only assumptions can be discussed here. There was no notable change in allocation policies at that time, MELD-based allocation was introduced in late 2006 in Germany as mentioned above. Furthermore, the clinical setting did not change significantly, just a slight increase in the application of Histidine-Tryptophane-Ketoglutarat (HTK) preservation solution could be detected in 2012. HTK-solution was suspected to be associated to biliary complications previously and a trend towards this association was shown in our center in previously published research[10,16].

The proposed prognostic model, which is basing on the results of regression analyses, was shown to have good predictive capabilities with an AUROC > 0.700. Furthermore, it could be internally validated successfully with 100 randomized backwards bootstraps. These promising results regarding this model warrant its validation in an external dataset, which is definitely necessary before a broad application in clinical transplantation seems useful. This validation is preferably performed in a prospective, multi-centric cohort or a large transplant registry, which contains all relevant data as described above.

This study is limited by its single center design and its retrospective character. Furthermore, the long observation period of three decades naturally includes changes in diagnostics and management of biliary complications. This circumstance was addressed with the categorization of the data into four eras, which was taken into account during statistical analysis.

Taken together, the results of the current study lead to the assumption that high recipient MELD scores in combination with impaired donor kidney function as depicted in donor creatinine levels at the time of transplantation should be avoided to protect the recipient from the onset of early biliary complications. This is especially the case, when HAT occurs in the post-transplant setting, which further endangers the recipient to develop serious anastomotic bile duct issues.

Biliary complications account for a great part of early issues after liver transplantation leading to re-intervention, serious morbidity and even mortality. Moreover, they are responsible for a high amount of healthcare costs after transplantation.

In recent years, studies were outlined and published to identify relevant risk factors for the development of biliary complications. However, long-term follow-up data and large series overlooking decades of liver transplant experience are scarce. There is especially no prognostic model available so far, which helps to identify patients who are threatened by this serious complication.

The results of this study should reduce the incidence of anastomotic biliary complications after liver transplantation. The proposed prognostic model for the prediction of anastomotic biliary complications can be a tool for the transplant clinician to identify patients at high risk for the development of biliary complications, which then can be included into a stricter diagnostic observation scheme, e.g., with repeating abdominal ultrasound examinations and blood works.

Biliary complications do regularly occur after liver transplantation. They can be classified into anastomotic (bile leak vs strictures) and non-anastomotic lesions. In many countries, liver grafts are currently allocated on the basis of the Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)-score, which is a score including the recipient’s bilirubine levels, creatinine levels as well as the coagulation state via the international normalized ratio-value. The MELD-score is able to reliably predict short-term death on the liver transplant waiting lists in many transplantation systems.

An interesting well-written study.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Akamatsu N, Allam N, Yu L S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Neuberger J, Ferguson J, Newsome PN. Liver transplantation - clinical assessment and management. Wiley Blackwell publishing, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2014: 216. . |

| 2. | Karimian N, Westerkamp AC, Porte RJ. Biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014;19:209-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Axelrod DA, Dzebisashvilli N, Lentine KL, Xiao H, Schnitzler M, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Segev DL. National assessment of early biliary complications after liver transplantation: economic implications. Transplantation. 2014;98:1226-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lu D, Xu X, Wang J, Ling Q, Xie H, Zhou L, Yan S, Wang W, Zhang M, Shen Y. The influence of a contemporaneous portal and hepatic artery revascularization protocol on biliary complications after liver transplantation. Surgery. 2014;155:190-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Seehofer D, Eurich D, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Neuhaus P. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: old problems and new challenges. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:253-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kochhar G, Parungao JM, Hanouneh IA, Parsi MA. Biliary complications following liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2841-2846. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sundaram V, Jones DT, Shah NH, de Vera ME, Fontes P, Marsh JW, Humar A, Ahmad J. Posttransplant biliary complications in the pre- and post-model for end-stage liver disease era. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:428-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Baccarani U, Isola M, Adani GL, Avellini C, Lorenzin D, Rossetto A, Currò G, Comuzzi C, Toniutto P, Risaliti A. Steatosis of the hepatic graft as a risk factor for post-transplant biliary complications. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13773] [Cited by in RCA: 12284] [Article Influence: 285.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaltenborn A, Gwiasda J, Amelung V, Krauth C, Lehner F, Braun F, Klempnauer J, Reichert B, Schrem H. Comparable outcome of liver transplantation with histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate vs. University of Wisconsin preservation solution: a retrospective observational double-center trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Miyagi S, Kawagishi N, Kashiwadate T, Fujio A, Tokodai K, Hara Y, Nakanishi C, Kamei T, Ohuchi N, Satomi S. Relationship Between Bile Duct Reconstruction and Complications in Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:1166-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weismüller TJ, Negm A, Becker T, Barg-Hock H, Klempnauer J, Manns MP, Strassburg CP. The introduction of MELD-based organ allocation impacts 3-month survival after liver transplantation by influencing pretransplant patient characteristics. Transpl Int. 2009;22:970-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Klose J, Klose MA, Metz C, Lehner F, Manns MP, Klempnauer J, Hoppe N, Schrem H, Kaltenborn A. Outcome stagnation of liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis in the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease era. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399:1021-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bernardi M, Gitto S, Biselli M. The MELD score in patients awaiting liver transplant: strengths and weaknesses. J Hepatol. 2011;54:1297-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Magder LS, Regev A, Mindikoglu AL. Comparison of seven liver allocation models with respect to lives saved among patients on the liver transplant waiting list. Transpl Int. 2012;25:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stewart ZA, Cameron AM, Singer AL, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Histidine-Tryptophan-Ketoglutarate (HTK) is associated with reduced graft survival in deceased donor livers, especially those donated after cardiac death. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:286-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |