Published online Jun 8, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i16.752

Peer-review started: January 19, 2017

First decision: March 8, 2017

Revised: April 3, 2017

Accepted: April 23, 2017

Article in press: April 24, 2017

Published online: June 8, 2017

Processing time: 139 Days and 3 Hours

Spontaneous rupture is one of the most fatal complications of hepatic tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma. In fact, many studies have shown that the in-hospital and 30-d mortality rates are as high as 25%-100%. Cholangiolocellular carcinoma (CoCC) is a rare primary hepatic tumor, usually small in size, that is thought to originate from the ductules and/or canals of Hering. Here, we present a case of spontaneous rupture of a CoCC that was successfully resected by radical surgery. Although CoCC is a rare primary hepatic tumor, it demonstrates certain specific clinical features, including a better prognosis than for other primary liver cancers, and thus should be distinguished from those other cancers. Moreover, CoCC can appear as a ruptured huge tumor, and when it does, radical hepatectomy can be an effective measure to achieve both absolute hemostasis and curability of tumor.

Core tip: Spontaneous rupture is one of the most fatal complications of hepatic tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma. Here, we present a case of spontaneous rupture of a cholangiolocellular carcinoma (CoCC) that was successfully resected by radical surgery. Although CoCC is a rare primary hepatic tumor, it demonstrates certain specific clinical features, including a better prognosis than for other primary liver cancers, and thus should be distinguished from those other cancers. Moreover, CoCC can appear as a ruptured huge tumor, and when it does, radical hepatectomy can be an effective measure to achieve both absolute hemostasis and curability of tumors.

- Citation: Akabane S, Ban T, Kouriki S, Tanemura H, Nakazaki H, Nakano M, Shinozaki N. Successful surgical resection of ruptured cholangiolocellular carcinoma: A rare case of a primary hepatic tumor. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(16): 752-756

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i16/752.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i16.752

Spontaneous tumor rupture is one of the most fatal complications of hepatic tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In fact, many studies have shown that the in-hospital and 30-d mortality rates are as high as 25%-100%[1]. Cholangiolocellular carcinoma (CoCC) is a rare primary hepatic tumor first described by Steiner and Higginson[2]. Subsequent reports characterized it based on small cords resembling cholangioles (canals of Hering). Although CoCC was previously classified as a special type of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), as a result of recent advancements in the field, it is now considered to originate from hepatic stem/progenitor cells.

Here, we present a case of spontaneous rupture of a CoCC that was successfully resected by radical surgery.

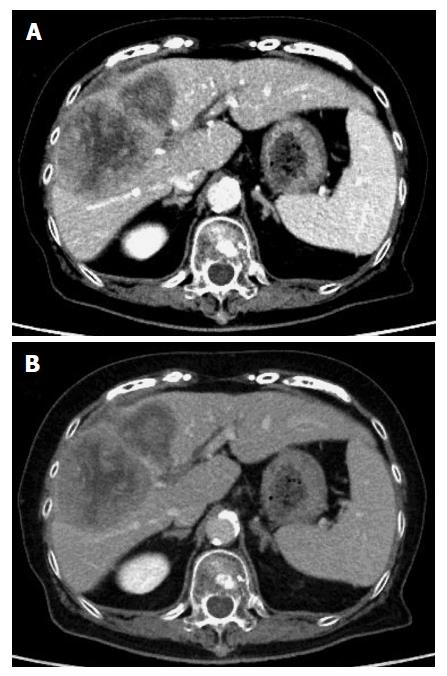

An 80-year-old Japanese woman presented with right upper abdominal pain that had developed within 2-3 h along with hypotension. She had not experienced vomiting or diarrhea. Her medical history included hypertension and dyslipidemia. On physical examination, there was tenderness in the right upper abdomen, and her body temperature was 36.5 °C. Laboratory tests were negative for anemia and thrombocytopenia and revealed bilirubin, transaminase and albumin levels in the normal range. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a huge tumor (12 cm × 7 cm × 9 cm) located in the right anterior segment of the liver along with extrahepatic hematoma (Figure 1).

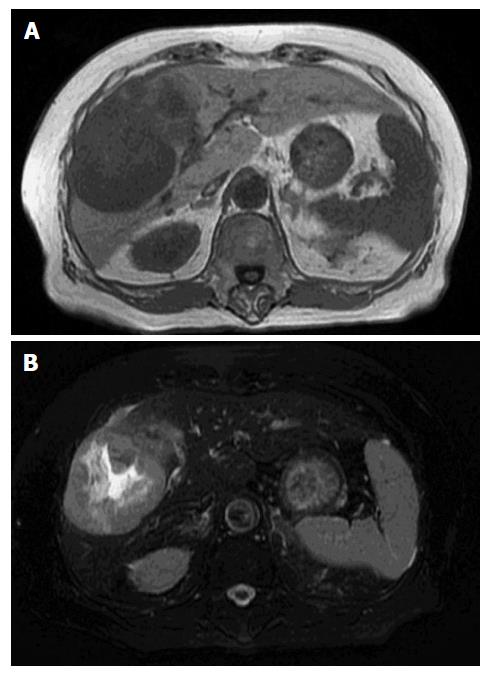

The tumor was hyperattenuating relative to the noncancerous liver parenchyma in the arterial phase and was hypo- or isoattenuating in the delayed phase, with central necrosis appearing as a low-density area. The axial T1-weighted gradient-echo image showed a hypointense mass in the right anterior segment of the liver, and the axial T2-weighted spin-echo image with fat suppression showed an isointense mass with a large central hyperintense area (Figure 2). In addition, the penetrating portal tract showed hyperintensity.

The patient was subsequently diagnosed with a ruptured hepatic tumor. Although emergency transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) was considered, she was hemodynamically stable due to fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion. As a result, primary right hemi-hepatectomy was performed. Following surgery, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and transferred to the general ward 5 d after surgery. Although it took time to improve her nutritional status and to rehabilitate her, she was discharged 30 d later without any complications.

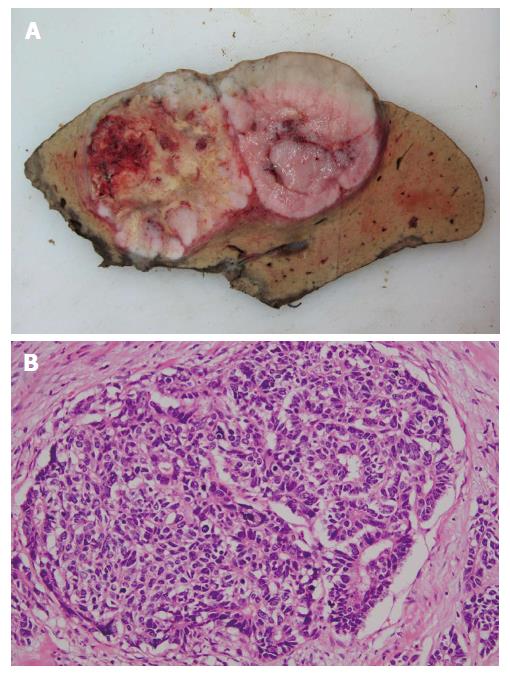

Histologically, the tumor was mainly composed of small, monotonous glands formed into antler-like anastomosing patterns, embedded in the fibrous stroma to various degrees of fibrous stroma and lacking mucin production (Figure 3). The presence of CoCC cells was confirmed by positive staining for cytokeratin 19 (CK19) and membranous positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), but no positive staining for hepatocyte paraffin 1 (HepPar1) was present (Figure 4).

So far, the patient has attended the outpatient clinic for follow-up for 1 year after surgery, with no signs of recurrence detected on CT scans.

This case highlights two important considerations. First, although CoCC is a rare primary hepatic tumor, it demonstrates certain specific clinical features and hence should be distinguished from other primary liver cancers, such as HCC or ICC. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the presentation of a CoCC with spontaneous tumor rupture that was successfully resected.

CoCC is derived from the cholangioles or canals of Hering and is characterized by small cords resembling cholangioles and ductular reaction-like anastomosing glands in abundant fibrous stroma. The canals of Hering are found in portal tracts of all sizes, where the canals connect with the bile duct. The ductules contain hepatic progenitor cells that can differentiate into both hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. Therefore, in the case of tumors derived from hepatic progenitor cells, characteristics of hepatocytic and cholangiocytic differentiation can be alternately displayed within the same tumor.

The clinical characteristics and imaging features of CoCC are similar to those of HCC and ICC. Many CoCC patients are infected with hepatitis C virus or hepatitis B virus, and angiographical hypervascularity is one of the characteristics of CoCC[3]; therefore, it is not surprising that CoCC has often been mistaken for HCC in the clinic[4].

Histologically, the presence of CoCC cells is further confirmed by either positive staining for CK19 or membranous positive staining for mucin core protein 1 and/or membranous positive staining for EMA but negative staining for HepPar1.

Patients with CoCC demonstrate favorable long-term survival after curative surgery. CoCC has been shown to be less invasive in the portal vein, as the number of patients with remaining portal tracts within their tumors was significantly higher in a CoCC group than in an ICC group[5]. Moreover, the number of patients with intrahepatic metastasis was significantly lower in a CoCC group than in an ICC group[6]. Furthermore, the 5-year overall survival rate and recurrence-free survival rate were significantly higher in a CoCC group than in an ICC group[7].

Spontaneous tumor rupture is one of the most fatal complications of hepatic tumors and is mainly determined by the growth characteristics of the tumor. The mechanism of tumor rupture has not been fully characterized; however, the literature[8] suggests that the pathogenesis may be associated with expansive growth and intratumoral pressure, which may cause tumor vein compression and congestion. The rapid growth of tumors also results in an insufficient blood supply to the tumors in vivo, causing tumor hypoxia-ischemia to occur, in turn resulting in significant necrosis.

As mentioned previously, CoCC grows relatively slowly and is less invasive, which results in a smaller tumor size (mean: 3.5 cm) than for other hepatic tumors[9]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing CoCC presenting as a huge tumor that had ruptured.

Emergency fluid resuscitation is a key therapeutic step for patients with hepatic tumor rupture. In particular, patients admitted to hospitals are treated with fast rehydration, anti-shock treatment, blood transfusion, and other supporting treatments to stabilize their circulation so that transhepatic artery angiography and embolization (that is, TAE) can be performed for hemostasis. For patients with continued bleeding, primary surgeries are performed to stop the bleeding. Hepatectomy, however, not only can stop bleeding immediately but also can make the radical resection of hepatic lesions possible as well as allowing for better long-term outcomes. There is still a possibility of rebleeding, even with temporarily controlled bleeding, in the case of spontaneous hepatic tumor ruptures[10,11]; hence, radical hepatectomy is an effective measure to address such emergencies. However, liver resection would be risky for patients with relatively poor liver function and/or severe liver cirrhosis[12]. Thus, TAE is more advantageous during initial hemostasis in emergency procedures for patients with hepatic tumor ruptures, especially in the case of high-surgical-risk patients. Once initial hemostasis is achieved using active supportive therapy, the patients may undergo staged hepatectomy.

In the case described here, the tumor was so huge that TAE was assumed to be anatomically difficult. In addition, the patient was hemodynamically stable due to fluid resuscitation, and her hepatic function was competent; thus, primary right hemi-hepatectomy was performed as a radical treatment.

CoCC is a rare primary hepatic tumor that demonstrates a better prognosis than for other primary liver cancers, such as HCC or ICC, and thus should be distinguished from those other cancers.

Moreover, CoCC can appear as a ruptured huge tumor, and when it does, radical hepatectomy can be an effective measure to achieve both absolute hemostasis and tumor cure.

An 80-year-old Japanese woman presented with right upper abdominal pain that had developed within 2-3 h along with hypotension.

There was tenderness in the right upper abdomen, and her body temperature was 36.5 °C.

Hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, metastatic hepatic tumor or hepatic abscess.

Laboratory test results were within the normal range. In particular, the patient was negative for anemia and thrombocytopenia, and her bilirubin, transaminase and albumin levels were in the normal range.

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showed a huge tumor located in the right anterior segment of the liver along with extrahepatic hematoma.

The tumor was mainly composed of small, monotonous glands formed into antler-like anastomosing patterns, embedded in the fibrous stroma to various degrees and lacking mucin production.

Fluid resuscitation, blood transfusion and primary right hemi-hepatectomy.

Spontaneous tumor rupture is one of the most fatal complications of hepatic tumors, and it is reported that the in-hospital and 30-d mortality rates are as high as 25%-100%.

Cholangiolocellular carcinoma (CoCC) was previously classified as a special type of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. However, as a result of recent advancements in the field, CoCC is now considered to originate from hepatic stem/progenitor cells.

CoCC can appear as a ruptured huge tumor, and when it does, radical hepatectomy can be an effective measure to achieve both absolute hemostasis and tumor cure.

Nice case report of successful surgical treatment of rare primary hepatic tumor. Excellent illustrations.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Galvao FHF, Kang KJ, Kamiyama T, Qin JM, Surani S, Tarazov PG S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Tso WK, Poon RT, Lam CM, Wong J. Management of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: single-center experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3725-3732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Steiner PE, Higginson J. Cholangiolocellular carcinoma of the liver. Cancer. 1959;12:753-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kanamoto M, Yoshizumi T, Ikegami T, Imura S, Morine Y, Ikemoto T, Sano N, Shimada M. Cholangiolocellular carcinoma containing hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocellular carcinoma, extremely rare tumor of the liver: a case report. J Med Invest. 2008;55:161-165. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Fukukura Y, Hamanoue M, Fujiyoshi F, Sasaki M, Haruta K, Inoue H, Aiko T, Nakajo M. Cholangiolocellular carcinoma of the liver: CT and MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:809-812. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Uenishi T, Yamazaki O, Tanaka H, Takemura S, Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, Nishiguchi S, Kubo S. Serum cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA21-1) as a prognostic factor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:583-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Campagnaro T, Pachera S, Valdegamberi A, Nicoli P, Cappellani A, Malfermoni G, Iacono C. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic factors after surgical resection. World J Surg. 2009;33:1247-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ariizumi S, Kotera Y, Katagiri S, Nakano M, Nakanuma Y, Saito A, Yamamoto M. Long-term survival of patients with cholangiolocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21 Suppl 3:S451-S458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Uchida E. Spontaneous ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maeno S, Kondo F, Sano K, Takada T, Asano T. Morphometric and immunohistochemical study of cholangiolocellular carcinoma: comparison with non-neoplastic cholangiole, interlobular duct and septal duct. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Barosa R, Figueiredo P, Fonseca C. Acute Anemia in a Patient With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. HCC Rupture With Intraperitoneal Hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:e3-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Recordare A, Bonariol L, Caratozzolo E, Callegari F, Bruno G, Di Paola F, Bassi N. Management of spontaneous bleeding due to hepatocellular carcinoma. Minerva Chir. 2002;57:347-356. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Han XJ, Su HY, Shao HB, Xu K. Prognostic factors of spontaneously ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7488-7494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |