Published online Apr 8, 2017. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i10.519

Peer-review started: October 21, 2016

First decision: January 5, 2017

Revised: January 23, 2017

Accepted: March 12, 2017

Article in press: March 13, 2017

Published online: April 8, 2017

Processing time: 167 Days and 16.5 Hours

To investigate the impact of hepatic encephalopathy before orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) and neurological complications after OLT on employment after OLT.

One hundred and fourteen patients with chronic liver disease aged 18-60 years underwent neurological examination to identify neurological complications, neuropsychological tests comprising the PSE-Syndrome-Test yielding the psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score, the critical flicker frequency and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), completed a questionnaire concerning their occupation and filled in the short form 36 (SF-36) to assess health-related quality of life before OLT and 12 mo after OLT, if possible. Sixty-eight (59.6%) patients were recruited before OLT, while on the waiting list for OLT at Hannover Medical School [age: 48.7 ± 10.2 years, 45 (66.2%) male], and 46 (40.4%) patients were included directly after OLT.

Before OLT 43.0% of the patients were employed. The patients not employed before OLT were more often non-academics (employed: Academic/non-academic 16 (34.0%)/31 vs not employed 10 (17.6%)/52, P = 0.04), had more frequently a history of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (yes/no; employed 15 (30.6%)/34 vs not employed 32 (49.2%)/33, P = 0.05) and achieved worse results in psychometric tests (RBANS sum score mean ± SD employed 472.1 ± 44.5 vs not employed 443.1 ± 56.7, P = 0.04) than those employed. Ten patients (18.2%), who were not employed before OLT, resumed work afterwards. The patients employed after OLT were younger [age median (range, min-max) employed 47 (42, 18-60) vs not employed 50 (31, 29-60), P = 0.01], achieved better results in the psychometric tests (RBANS sum score mean ± SD employed 490.7 ± 48.2 vs not employed 461.0 ± 54.5, P = 0.02) and had a higher health-related quality of life (SF 36 sum score mean ± SD employed 627.0 ± 138.1 vs not employed 433.7 ± 160.8; P < 0.001) compared to patients not employed after OLT. Employment before OLT (P < 0.001), age (P < 0.01) and SF-36 sum score 12 mo after OLT (P < 0.01) but not HE before OLT or neurological complications after OLT were independent predictors of the employment status after OLT.

HE before and neurological complications after OLT have no impact on the employment status 12 mo after OLT. Instead younger age and employment before OLT predict employment one year after OLT.

Core tip: This prospective study is the first to consider hepatic encephalopathy prior to liver transplantation, neurological complications after liver transplantation as well as socio-economic factors as risk factors for unemployment 1 year after transplantation. Our data confirm that employment status before liver transplantation is most important in predicting the employment status 12 mo after transplantation. However, neither prior-liver transplantation hepatic encephalopathy nor neurological complications after liver transplantation are independent risk factors for unemployment 1 year after transplantation.

- Citation: Pflugrad H, Tryc AB, Goldbecker A, Strassburg CP, Barg-Hock H, Klempnauer J, Weissenborn K. Hepatic encephalopathy before and neurological complications after liver transplantation have no impact on the employment status 1 year after transplantation. World J Hepatol 2017; 9(10): 519-532

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v9/i10/519.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v9.i10.519

During the last 35 years specialized transplantation centres with outpatient clinics for follow-up and improvement of immunosuppressive therapy have significantly increased survival rates after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT)[1]. Thus, additional indicators of treatment quality besides mortality, such as employment after OLT, emerged. Employment after OLT indicates reintegration into society, regain of cognitive and physical capability and increased health-related quality of life (HRQoL)[2]. Although reintegration of patients into work is pursued, actually, only about 50% of the patients work after OLT, and there are significant differences between different countries with rates ranging between 17% and 55%[3-8]. Reasons why patients do not work after OLT are believed to be manifold. Local social security insurance system, age, sex, level of vocational training, level of school education, type of work, disability, unemployment before OLT, underlying liver disease, high morbidity due to liver disease and complications after OLT have been discussed[4,9]. Hereof, employment itself and the type of employment before OLT were considered to be the most important predictors of post OLT employment[3]. Interestingly, neither hepatic encephalopathy (HE) before OLT nor neurological complications after OLT have been considered in this respect so far even though both can significantly impact patients’ physical and mental ability before and after OLT.

HE is a frequent complication of liver cirrhosis caused by liver insufficiency and porto-systemic shunts[10]. It is based on neurochemical and neurophysiological disorders of the brain and although the pathogenesis of HE is not completely understood, ammonia is believed to be of major importance[11]. HE is characterized by deficits in motor accuracy and motor speed as well as cognitive impairment especially concerning attention, whereas verbal abilities maintain unaffected[12]. HE is present in about 10%-50% of patients at the time of transplantation and about 35%-45% of OLT patients have a history of HE[13]. Neurological complications like encephalopathy, seizures, tremor, psychotic disorders and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome occur in about 30% of the patients after OLT[14]. They result in a high morbidity and prolonged in-hospital stay[15]. HE prior OLT and neurological complications after OLT have not been distinctly considered as risk factors for unemployment after OLT so far, probably because HE was considered to be completely reversible[16], and neurological complications after OLT - though frequent - are usually impairing the patients cognitive function only transiently[14,15,17].

However, HE is known to have an impact on patients’ working ability before OLT, especially of blue collar workers[18], and neurological complications possibly impair recovery of working capability after OLT[15]. The main hypothesis of this prospective study was that hepatic encephalopathy before OLT and neurological complications after OLT are significantly associated with unemployment one year after OLT. Furthermore, we analysed whether employment status before OLT, occupation, underlying liver disease, health-related quality of life, quality adjusted life years (QALYs), age and sex are significantly associated with the employment status one year after OLT.

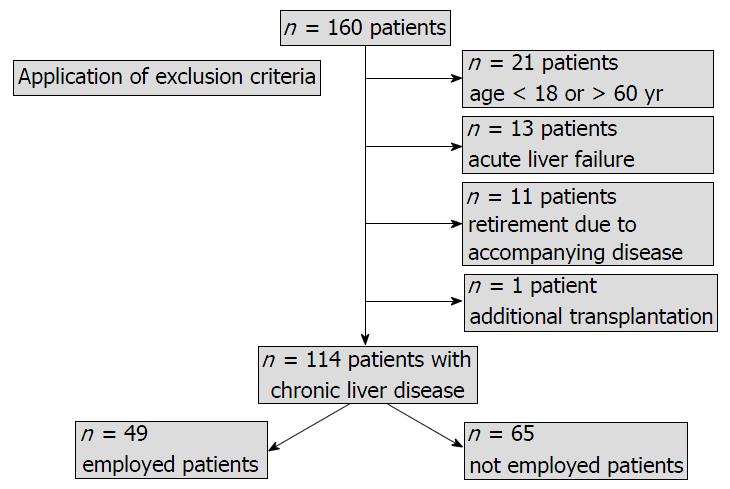

All patients included into this study took part in a long-term prospective follow-up study of patients after liver transplantation (n = 160). Patients with liver cirrhosis, admission to the waiting list for liver transplantation, acute liver failure and age between 18 and 80 years were included into the follow-up study. For the present study patients with acute liver failure, neurological or psychiatric diseases not related to hepatic encephalopathy, additional transplantation of another organ, regular intake of medication with an effect on the central nervous system (CNS), age older than 60 years at OLT because of the high probability of age related retirement and the expected low probability of reintegration into employment after OLT, retirement due to conclusion of work life, accompanying disease or age were excluded. Finally, data of 114 patients with chronic liver disease were considered for the analysis (Figure 1). Sixty-eight (59.6%) patients were recruited before OLT, while on the waiting list for liver transplantation at Hannover Medical School [age: 48.7 ± 10.2 years, 45 (66.2%) male], and 46 (40.4%) patients were included directly after OLT [age: 44.9 ± 11.4 years, 27 (58.7%) male].

All subjects gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and performed according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2008).

Patients recruited before OLT regularly underwent neurological examinations by a neurologist of the group before OLT if possible and all patients included underwent a neurological examination on day 1, day 7, day 90 and approximately 12 mo after OLT. If the examination was not possible 12 mo after OLT, it was done at a later point of time within the follow-up study. Additional neurological examinations were performed when necessary. Encephalopathy, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, alterations of consciousness, seizures, hallucinations, confusion, infections of the CNS, intracerebral bleeding or stroke were classified as neurological complications. Neurological complications were assessed as a categorical variable independent from the time of occurrence within the immediate hospital stay after OLT.

If possible, a psychometric test battery for the assessment of attention, concentration, memory, speed of information processing, visuo-constructive abilities, motor speed and accuracy and executive functions comprising the PSE-Syndrome-Test, a battery that provides the psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score (PHES)[19], the critical flicker frequency (CFF)[20] and the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)[21,22] were applied by a neurologist of the group trained in these tests. The median interval between the psychometric testing before OLT and the transplantation was 4 mo (interquartile range 5 mo, min 0, max 33) and the median interval between OLT and psychometric testing after OLT was 12 mo (interquartile range 5 mo, min 10, max 62). Furthermore, the patients were asked to complete questionnaires concerning occupation and HRQoL [short form 36 (SF-36)][23]. The SF-36 evaluation was performed according to its scoring algorithm yielding 8 domain scores: Physical functioning (PF), physical role functioning (PRF), bodily pain (BP), general health perception (GHP), vitality (VIT), social role functioning (SRF), emotional role functioning (ERF) and mental health (MH) which were summated for the SF-36 sum score. The default summary measures physical health and mental health were not calculated because they are based on American standard values.

The six-dimension health state short form (SF-6D)[24] was derived from the SF-36 by generating six multi-level dimensions that provide a health status which ranges from 1 (full health) to 0 (death). It is based on preference weights gained from the United Kingdom general population and estimates a preference-based single index measure for health to measure QALYs.

Individual test results were evaluated by comparison to norm values given in the test manuals. The scores of the psychometric batteries were adjusted for age and education. Reasons for missing data before OLT were language issues, inclusion of the patient after OLT or refusal by the patient to complete the tests or questionnaires. After OLT data is missing due to refusal by the patient to complete the tests or questionnaires, language issues or death after OLT.

Age, occupation, underlying liver disease, laboratory Model of End Stage Liver Disease (labMELD) score and medication were assessed and documented. The history of HE was taken from reliable case records in which HE was diagnosed and scored by physicians according to the West Haven criteria[25].

Self-reporting questionnaire occupation: The patients selected which of the following specifications applied to their situation: Employed, retired (receiving pension due to illness), unemployed, certified unfit for work, homemaker or in training at school or university. Patients on a full time or part time job, students and homemakers were classified as employed. Although Patients with the status “student” or “homemaker” were not working for a wage, they were classified as employed because the authors are convinced that studying or keeping the house requires physical and mental capability which equals the requirements that are needed to work for a wage. The not employed patient group consisted of patients that were unemployed, temporarily certified unfit for work or retired due to liver disease (Table 1). For subgroup analysis the patients were allocated according to their employment status before and after OLT into the groups employed before and after OLT, employed before but not employed after OLT, not employed before and after OLT as well as not employed before but employed after OLT. Patients with a university degree were classified as academics and patients with a vocational training for qualification were classified as non-academics. These data were surveyed retrospectively for patients included after OLT from case records or by anamneses.

Statistical methods: Normality of distribution was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between the groups of employed and not employed patients concerning age, labMELD score, psychometric test results and SF-36 scores were evaluated with the Mann-Whitney test for not normal distributed values and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normal distributed values. The Wilcoxon test or the paired sample T-test was used to compare related values concerning psychometric test results and SF-36 scores surveyed before and after OLT. Categorical variables comprising sex, profession, history of HE and neurological complications were tested by Fisher’s Exact Test and the underlying liver disease was tested by theχ2 test. Binary logistic regression analysis (Method = Enter) was applied to identify independent prognostic factors for employment after OLT as the dependent variable considering employment before OLT, underlying liver disease, labMELD score, history of HE, neurological complications after OLT, age, sex, profession, SF-36 sum score before OLT and SF-36 sum score 12 mo after OLT as independent parameters. For the regression model the Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients, the -2 Log likelihood, the Nagelkerke R Square and the effects size Cohen’s d values are shown. For the variables in the Equation significant at the 0.05 level, Wald statistic, P value, the Odds ratio [Exp(B)] and the confidence interval for the Odss ratio [Exp(B)] are given. Normally distributed values are shown as mean ± SD and not normally distributed values are shown as median with range. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant for all tests applied. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Prof Hecker, former Head of the Biostatistics Department at Hannover Medical School.

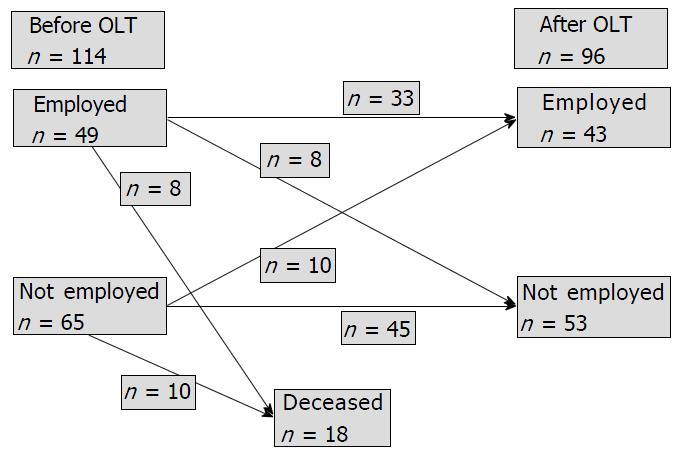

Forty-nine (43.0%) of the 114 patients were employed at the time of OLT compared to 65 (57.0%) who were not employed (Figure 2). The two patient groups did not differ with regard to age, sex, the severity of liver disease according to the labMELD score, or with regard to aetiology of liver disease. Patients who were not employed before OLT had significantly more often a positive history of HE, were more frequently non-academic (82% vs 66%) and showed a significantly lower value in the SF-36 domain score physical functioning, whereas all other SF-36 domain scores and the QALYs did not differ. Furthermore, they achieved significantly worse results in the PHES and the RBANS sum score (Table 2).

| n = 114 | Employed (n = 49) | Not employed (n = 65) | P value |

| Age median (range, min-max) | 49 (42,18-60) | 50 (36, 24-60) | 0.06 |

| Sex (male/female) | 30 (61.2%)/19 | 42 (64.6%)/26 | 0.85 |

| Profession Academic/non-academic | 16 (34.0%)/31 (NS 2) | 10 (17.6%)/52 (NS 3) | 0.04 |

| labMELD median (range, min-max) | 18 (33, 7-40) | 18 (33, 7-40) | 0.16 |

| Aetiology of liver disease | 0.44 | ||

| PSC | 16 | 14 | |

| PBC | 0 | 1 | |

| Alcohol | 5 | 10 | |

| HCV | 7 | 11 | |

| HBV | 5 | 13 | |

| AIH | 3 | 1 | |

| M. Wilson | 3 | 1 | |

| Others | 10 | 14 | |

| History of HE (+/-) | 15 (30.6%)/34 | 32 (49.2%)/33 | 0.05 |

| PHES, median (min/max) | 0 (-8/+5) (n = 27) | -2 (-18/+4) (n = 37) | 0.04 |

| CFF, mean ± SD | 42.7 ± 3.9 (n = 26) | 42.3 ± 5.0 (n = 35) | 0.77 |

| RBANS Immediate memory, mean ± SD | 92.2 ± 17.0 (n = 24) | 89.6 ± 18.6 (n = 32) | 0.59 |

| RBANS Visuospatial/constructional, median (range, min-max) | 84 (60, 66-126) (n = 24) | 84 (66, 60-126) (n = 32) | 0.26 |

| RBANS Language, mean ± SD | 99.3 ± 11.6 (n = 24) | 96.2 ± 14.4 (n = 32) | 0.40 |

| RBANS Attention, mean ± SD | 91.8 ± 17.3 (n = 24) | 84.2 ± 16.6 (n = 32) | 0.10 |

| RBANS Delayed memory, median (range, min-max) | 97 (36, 86-122) (n = 24) | 94.5 (64, 44-108) (n = 32) | 0.24 |

| RBANS Sum score, mean ± SD | 472.1 ± 44.5 (n = 24) | 443.1 ± 56.7 (n = 32) | 0.04 |

| RBANS Total scale, mean ± SD | 92.1 ± 11.6 (n = 24) | 84.9 ± 14.4 (n = 32) | 0.05 |

Twelve month after OLT 43 (44.8% of those who survived) patients were employed (including students and homemakers) and 53 (55.2%) patients were not employed. Eighteen of the included 114 patients died after OLT (15.8%). The cause of death was multi-organ failure in 5 cases, sepsis, heart failure or abdominal bleeding in 3 cases each, subarachnoid haemorrhage in one case, meningitis/encephalitis in one case and unknown in 2 cases. Eight of these were employed (16.3%) and 10 (15.4%) were not employed before OLT. Eight of the patients who were employed before OLT did not return to employment after OLT (19.5% of those who survived, n = 41), while 33 (80.5% of those who survived) returned to work. Of those survivors who were not employed before OLT (n = 55), 10 (18.2%) returned to work within the year after transplantation, while 45 (81.8%) remained not employed (Figure 2).

Patients not employed 12 mo after OLT were significantly older and showed significantly worse results in the psychometric tests after OLT than the employed patients (Table 3).

| n = 96 | Employed (n = 43) | Not employed (n = 53) | P value |

| Age median (range, min-max) | 47 (42, 18-60) | 50 (31, 29-60) | 0.01 |

| Sex (male/female) | 23 (53.5%)/20 | 36 (67.9%)/17 | 0.21 |

| Profession Academic/non-academic | 13 (31.0%)/29 (NS 1) | 8 (15.1%)/45 | 0.08 |

| labMELD median (range, min-max) | 18 (33, 7-40) | 19 (33, 7-40) | 0.16 |

| Aetiology of liver disease | 0.41 | ||

| PSC | 15 | 13 | |

| PBC | 1 | 0 | |

| Alcohol | 4 | 8 | |

| HCV | 7 | 6 | |

| HBV | 3 | 12 | |

| AIH | 2 | 1 | |

| M. Wilson | 2 | 1 | |

| Others | 9 | 12 | |

| History of HE (+/-) | 13 (30.2%)/30 | 25 (47.2%)/28 | 0.10 |

| Neurological complications (+/-) | 17 (39.5%)/26 | 30 (56.6%)/23 | 0.11 |

| PHES, median (min/max) | 0 (-5/+2) (n = 30) | -1 (-10/+4) (n = 43) | 0.10 |

| CFF, mean ± SD | 45.8 ± 4.0 (n = 29) | 42.0 ± 4.1 (n = 40) | < 0.001 |

| RBANS Immediate memory, mean ± SD | 101.1 ± 15.1 (n = 30) | 92.1 ± 17.7 (n = 41) | 0.03 |

| RBANS Visuospatial/constructional, median (range, min-max) | 84 (64, 62-126) (n = 30) | 89 (57, 64-121) (n = 41) | 0.17 |

| RBANS Language, mean ± SD | 103.2 ± 13.9 (n = 30) | 93.0 ± 16.5 (n = 41) | 0.01 |

| RBANS Attention, mean ± SD | 101.2 ± 13.7 (n = 30) | 89.3 ± 15.5 (n = 41) | 0.001 |

| RBANS Delayed memory, median (range, min-max) | 98 (109, 10-119) (n = 30) | 95 (44, 75-119) (n = 41) | 0.13 |

| RBANS Sum score, mean ± SD | 490.7 ± 48.2 (n = 30) | 461.0 ± 54.5 (n = 41) | 0.02 |

| RBANS Total scale, mean ± SD | 97.4 ± 13.6 (n = 30) | 89.6 ± 14.2 (n = 41) | 0.02 |

HE (P = 0.10) before OLT and neurological complications (P = 0.11) after OLT were more frequent in not employed patients after OLT, but the difference did not reach statistical significance at the 0.05 level. Concerning the HRQoL, all SF-36 domain scores and the QALYs were significantly higher in the group of employed patients compared to the not employed patients after OLT (Table 4). There was no significant difference for all other parameters tested.

| SF-36 domain score | Before OLT | P value | After OLT | P value | ||

| Employed (n = 27) | Not employed (n = 35) | Employed (n = 30) | Not employed (n = 41) | |||

| PF, mean ± SD | 70.7 ± 25.1 | 47.4 ± 27.4 | 0.001 | 82.3 ± 19.2 | 59.4 ± 28.2 | < 0.001 |

| PRF, median (range, min-max) | 50 (100, 0-100) | 25 (100, 0-100) | 0.14 | 100 (100, 0-100) | 25 (100, 0-100) | < 0.001 |

| BP, median (range, min-max) | 74 (100, 0-100) | 51 (100, 0-100) | 0.14 | 100 (69, 31-100) | 74 (88, 12-100) | 0.001 |

| GHP, median (range, min-max) | 40 (77, 10-87) | 35 (82, 0-82) | 0.71 | 69.5 (87, 10-97) | 50 (87, 10-97) | 0.01 |

| VIT, median (range, min-max) | 45 (80, 10-90) | 40 (85, 0-85) | 0.43 | 70 (75, 20-95) | 45 (85, 5-90) | 0.001 |

| SRF, median (range, min-max) | 87.5 (87.5, 12.5-100) | 62.5 (87.5, 12.5-100) | 0.52 | 100 (50, 50-100) | 62.5 (87.5, 12.5-100) | < 0.001 |

| ERF, median (range, min-max) | 100 (100, 0-100) | 100 (100, 0-100) | 0.94 | 100 (100, 0-100) | 33.3 (100, 0-100) | < 0.001 |

| MH, median (range, min-max) | 76 (60, 32-92) | 64 (88, 8-96) | 0.31 | 80 (56, 44-100) | 68 (72, 28-100) | 0.01 |

| Sum score, mean ± SD | 479.2 ± 193.9 | 419.7 ± 169.7 | 0.20 | 627.0 ± 138.1 | 433.7 ± 160.8 | < 0.001 |

| SF-6D QALYs, mean ± SD | 0.71 ± 0.14 | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | < 0.001 |

Patients employed before and after OLT (n = 33) other than patients employed before but not employed after OLT (n = 8) showed significantly better values in the CFF (P = 0.04) and higher scores in the RBANS domain scores immediate memory (P = 0.04) and attention (P = 0.04) after OLT (Table 5). Furthermore, the health related quality of life scores after OLT were significantly higher in patients reintegrated into employment after OLT compared to the patients not reemployed after OLT (Table 6).

| n = 41 | Employed before and after OLT (n = 33) | Employed before but not employed after OLT (n = 8) | P value |

| Age, median (range, min-max) | 50 (42, 18-60) | 54 (30, 29-59) | 0.13 |

| Sex (male/female) | 18 (54.5%)/15 | 6 (75.0%)/2 | 0.43 |

| Profession Academic/non-academic | 11 (34.4%)/21 (NS 1) | 3 (37.5%)/5 | 1.00 |

| labMELD median (range, min-max) | 18 (33, 7-40) | 17 (31, 9-40) | 0.91 |

| Aetiology of liver disease | 0.19 | ||

| PSC | 12 | 2 | |

| PBC | 0 | 0 | |

| Alcohol | 3 | 0 | |

| HCV | 6 | 0 | |

| HBV | 2 | 2 | |

| AIH | 2 | 1 | |

| M. Wilson | 2 | 0 | |

| Others | 6 | 3 | |

| History of HE (+/-) | 9 (27.3%)/24 | 2 (25.0%)/6 | 1.00 |

| Neurological complications (+/-) | 11 (33.3%)/22 | 5 (62.5%)/3 | 0.23 |

| PHES after OLT, median (min/max) | 1 (-4/+2) (n = 25) | 0 (-7/+4) (n = 7) | 0.93 |

| CFF after OLT, mean ± SD | 45.3 ± 3.7 (n = 24) | 41.7 ± 5.0 (n = 7) | 0.04 |

| RBANS after OLT Immediate memory, mean ± SD | 101.6 ± 14.1 (n = 26) | 89.4 ± 10.0 (n = 7) | 0.04 |

| RBANS after OLT Visuospatial/constructional median (range, min-max) | 84 (64, 62-126) (n = 26) | 89 (57, 64-121) (n = 7) | 0.68 |

| RBANS after OLT Language, mean ± SD | 103.2 ± 14.6 (n = 26) | 95.1 ± 24.2 (n = 7) | 0.27 |

| RBANS after OLT Attention, mean ± SD | 100.8 ± 14.1 (n = 26) | 87.1 ± 18.6 (n = 7) | 0.04 |

| RBANS after OLT Delayed memory, median (range, min-max) | 98 (109, 10-119) (n = 26) | 95 (17, 88-105) (n = 7) | 0.16 |

| RBANS after OLT Sum score, mean ± SD | 492.0 ± 47.8 (n = 26) | 457.0 ± 56.8 (n = 7) | 0.11 |

| RBANS after OLT Total scale, mean ± SD | 97.7 ± 13.7 (n = 26) | 88.3 ± 14.6 (n = 7) | 0.12 |

| SF-36 domain score | Before OLT | P value | After OLT | P value | ||

| Employed before and after OLT (n = 17) | Employed before and not employed after OLT (n = 4) | Employed before and after OLT (n = 26) | Employed before and not employed after OLT (n = 7) | |||

| PF, mean ± SD | 75.9 ± 23.8 | 55.0 ± 31.6 | 0.15 | 84.6 ± 17.0 | 45.0 ± 23.5 | < 0.001 |

| PRF, median (range, min-max) | 50 (100, 0-100) | 62.5 (50, 25-75) | 0.97 | 100 (100, 0-100) | 25 (50, 0-50) | 0.001 |

| BP, median (range, min-max) | 84 (100, 0-100) | 81 (48, 52-100) | 0.90 | 100 (49, 51-100) | 52 (78, 22-100) | 0.03 |

| GHP, median (range, min-max) | 50 (72, 10-82) | 35 (42, 25-67) | 0.64 | 72 (77, 20-97) | 60 (72, 15-87) | 0.31 |

| VIT, median (range, min-max) | 45 (80, 10-90) | 42.5 (60, 20-80) | 0.97 | 70 (75, 20-95) | 50 (70, 10-80) | 0.04 |

| SRF, median (range, min-max) | 87.5 (87.5, 12.5-100) | 87.5 (50, 50-100) | 0.70 | 100 (37.5, 62.5-100) | 50 (62.5, 37.5-100) | < 0.01 |

| ERF, median (range, min-max) | 100 (100, 0-100) | 66.7 (100, 0-100) | 0.70 | 100 (100, 0-100) | 33.3 (100, 0-100) | 0.05 |

| MH, median (range, min-max) | 72 (60, 32-92) | 74 (24, 56-80) | 0.83 | 82 (48, 52-100) | 76 (56, 44-100) | 0.22 |

| Sum score, mean ± SD | 512.1 ± 193.4 | 487.1 ± 172.2 | 0.82 | 652.9 ± 100.7 | 418.5 ± 121.5 | < 0.001 |

| SF-6D QALYs, mean ± SD | 0.72 ± 0.14 | 0.72 ± 0.15 | 0.94 | 0.83 ± 0.1 | 0.65 ± 0.10 | < 0.001 |

In the subgroup of 10 patients (18.2%) that were not employed before OLT but returned to work within 1 year after OLT, 5 were male (50%) and the median age was 41 (range 34, min 26, max 60) years. The qualification was a vocational education in 8 and a university degree in 2 cases. The reason for OLT was primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in 3 patients, primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, kryptogenic cirrhosis, biliary atresia and Budd-Chiari syndrome in 1 patient, respectively. The median labMELD score was 20 (range 24, min 8, max 32). Four patients had a history of HE before OLT and 6 patients had a neurological complication directly after OLT. All 10 patients returned to a job working for a wage after OLT. The comparison of the psychometric test results and the health related quality of life scores after OLT of this subgroup compared to patients that were not employed before and after OLT (n = 45) showed no significant group differences except that the patients reintegrated into employment after OLT were significantly younger (P = 0.03) and had significantly better CFF values (P < 0.01) after OLT than the patients that stayed not employed after OLT (Tables 7 and 8).

| n = 55 | Not Employed before and after OLT (n = 45) | Not employed before but employed after OLT (n = 10) | P value |

| Age, median (range, min-max) | 50 (28, 32-60) | 41 (34, 26-60) | 0.03 |

| Sex (male/female) | 30 (66.7%)/15 | 5 (50%)/5 | 0.47 |

| Profession Academic/non-academic | 5 (11.1%)/40 | 2 (20%)/8 | 0.6 |

| labMELD median (range, min-max) | 19 (33, 7-40) | 20 (24, 8-32) | 0.74 |

| Aetiology of liver disease | 0.2 | ||

| PSC | 11 | 3 | |

| PBC | 0 | 1 | |

| Alcohol | 8 | 1 | |

| HCV | 6 | 1 | |

| HBV | 10 | 1 | |

| AIH | 0 | 0 | |

| M. Wilson | 1 | 0 | |

| Others | 9 | 3 | |

| History of HE (+/-) | 23 (51.1%)/22 | 4 (40%)/6 | 0.73 |

| Neurological complications (+/-) | 25 (55.6%)/20 | 6 (60%)/4 | 1.0 |

| PHES after OLT, median (min/max) | -1 (-10/+4) (n = 36) | 0 (-5/+2) (n = 5) | 0.63 |

| CFF after OLT, mean ± SD | 42.0 ± 4.0 (n = 33) | 47.9 ± 5.2 (n = 5) | < 0.01 |

| RBANS after OLT Immediate memory, mean ± SD | 92.7 ± 19.0 (n = 34) | 97.8 ± 22.9 (n = 4) | 0.62 |

| RBANS after OLT Visuospatial/constructional, median (range, min-max) | 90.5 (55, 66-121) (n = 34) | 84 (11, 78-89) (n = 4) | 0.32 |

| RBANS after OLT Language, mean ± SD | 92.5 ± 14.8 (n = 34) | 103.5 ± 10.3 (n = 4) | 0.16 |

| RBANS after OLT Attention, mean ± SD | 89.7 ± 15.1 (n = 34) | 104.0 ± 12.6 (n = 4) | 0.08 |

| RBANS after OLT Delayed memory, median (range, min-max) | 96 (44, 75-119) (n = 34) | 98.5 (34, 71-105) (n = 4) | 1.0 |

| RBANS after OLT Sum score, mean ± SD | 461.9 ± 54.8 (n = 34) | 482.3 ± 57.6 (n = 4) | 0.49 |

| RBANS after OLT Total scale, mean ± SD | 89.9 ± 14.3 (n = 34) | 95.0 ± 14.5 (n = 4) | 0.51 |

| SF-36 domain score | Before OLT | P value | After OLT | P value | ||

| Not employed before and after OLT (n = 25) | Not employed before but employed after OLT (n = 6) | Not employed before and after OLT (n = 34) | Not employed before but employed after OLT (n = 4) | |||

| PF, mean ± SD | 48.2 ± 26.8 | 57.5 ± 26.0 | 0.45 | 62.4 ± 28.5 | 67.5 ± 28.4 | 0.74 |

| PRF, median (range, min-max) | 25 (100, 0-100) | 62.5 (100, 0-100) | 0.45 | 25 (100, 0-100) | 25 (100, 0-100) | 1.0 |

| BP, median (range, min-max) | 51 (100, 0-100) | 56.5 (78, 22-100) | 0.79 | 74 (88, 12-100) | 52.5 (69, 31-100) | 0.70 |

| GHP, median (range, min-max) | 35 (67, 15-82) | 43.5 (52, 0-52) | 0.64 | 46 (87, 10-97) | 41 (70, 10-80) | 0.73 |

| VIT, median (range, min-max) | 40 (80, 5-85) | 45 (65, 0-65) | 0.79 | 45 (85, 5-90) | 42.5 (35, 40-75) | 0.70 |

| SRF, median (range, min-max) | 62.5 (87.5, 12.5-100) | 81.3 (50, 50-100) | 0.42 | 62.5 (87.5, 12.5-100) | 68.8 (50, 50-100) | 0.77 |

| ERF, median (range, min-max) | 100 (100, 0-100) | 66.7 (67.7, 33.3-100) | 0.21 | 33.3 (100, 0-100) | 66.7 (66.7, 33.3-100) | 0.48 |

| MH, median (range, min-max) | 68 (88, 8-96) | 68 (80, 16-96) | 0.79 | 68 (68, 28-96) | 54 (56, 44-100) | 0.57 |

| Sum score, mean ± SD | 419.4 ± 166.3 | 480.8 ± 180.4 | 0.43 | 436.9 ± 169.1 | 458.5 ± 237.3 | 0.82 |

| SF-6D QALYs, mean ± SD | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.71 ± 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 0.65 ± 0.14 | 0.87 |

Thirty-seven patients filled in the questionnaires before and 12 mo after OLT. Of these, 16 patients were employed and 21 patients were not employed one year after OLT.

The HRQoL and the QALYs significantly increased after OLT in the 16 patients that were employed after OLT (Table 9). In contrast, the patients not employed after OLT (n = 21) did not show a significant change concerning their HRQoL with the exception of the SF-36 domain scores physical functioning and general health perception, which both increased significantly after OLT (Table 10).

| SF-36 domain score, n = 16 | Before OLT | After OLT | P value |

| PF, mean ± SD | 71.6 ± 26.8 | 84.1 ± 18.6 | 0.04 |

| PRF, mean ± SD | 50.0 ± 47.4 | 82.8 ± 35.0 | 0.02 |

| BP, mean ± SD | 70.7 ± 34.5 | 88.8 ± 18.8 | 0.04 |

| GHP, mean ± SD | 46.9 ± 24.0 | 66.8 ± 24.0 | 0.01 |

| VIT, mean ± SD | 45.9 ± 23.8 | 68.4 ± 15.2 | 0.01 |

| SRF, mean ± SD | 70.3 ± 33.2 | 90.6 ± 15.5 | 0.06 |

| ERF, mean ± SD | 70.8 ± 43.7 | 91.7 ± 19.3 | 0.10 |

| MH, mean ± SD | 70.8 ± 18.7 | 80.0 ± 13.6 | 0.17 |

| Sum score, mean ± SD | 497.0 ± 191.7 | 653.2 ± 128.6 | 0.01 |

| SF-6D QALYs, mean ± SD | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.10 | 0.02 |

| SF-36 domain score, n = 21 | Before OLT | After OLT | P value |

| PF, mean ± SD | 48.1 ± 28.3 | 65.5 ± 29.0 | 0.03 |

| PRF, mean ± SD | 38.1 ± 40.0 | 41.6 ± 39.0 | 0.76 |

| BP, mean ± SD | 61.1 ± 31.3 | 70.0 ± 24.8 | 0.25 |

| GHP, mean ± SD | 41.8 ± 15.6 | 56.8 ± 22.2 | 0.01 |

| VIT, mean ± SD | 44.3 ± 20.0 | 51.2 ± 22.2 | 0.14 |

| SRF, mean ± SD | 65.5 ± 29.3 | 67.3 ± 21.1 | 0.80 |

| ERF, mean ± SD | 55.6 ± 45.1 | 57.1 ± 44.9 | 0.91 |

| MH, mean ± SD | 66.3 ± 16.3 | 69.1 ± 18.7 | 0.53 |

| Sum score, mean ± SD | 420.7 ± 163.8 | 478.6 ± 148.0 | 0.21 |

| SF-6D QALYs, mean ± SD | 0.64 ± 0.15 | 0.66 ± 0.10 | 0.46 |

Forty-two patients completed the PHES (n = 16 employed after OLT), 36 patients the RBANS (n = 13 employed after OLT) and 38 patients the CFF (n = 15 employed after OLT) before and after OLT.

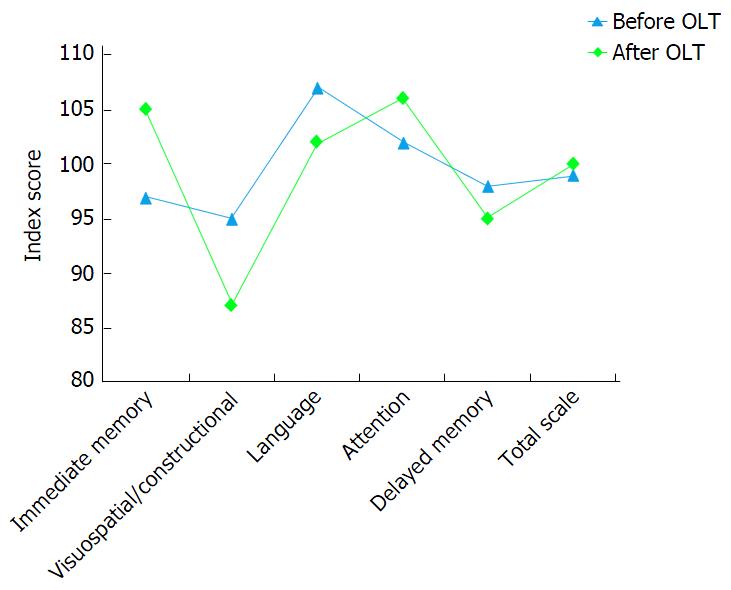

In the group of patients employed 12 mo after OLT, the PHES and the RBANS did not change significantly whereas the CFF increased significantly after OLT (PHES: n = 16; median 1.0, range 19 (min -14, max 5) before OLT, median 1.0, range 7 (min -5, max 2) after OLT, P = 0.26; CFF: n = 15; before OLT mean 43.3 Hz ± 3.8, after OLT mean 45.6 Hz ± 4.6, P = 0.04; RBANS: n = 13; immediate memory P = 0.08, visuospatial/constructional P = 0.17, language P = 0.21, attention P = 0.34, delayed memory P = 0.44, sum score P = 0.70, total scale P = 0.79 (Figure 3).

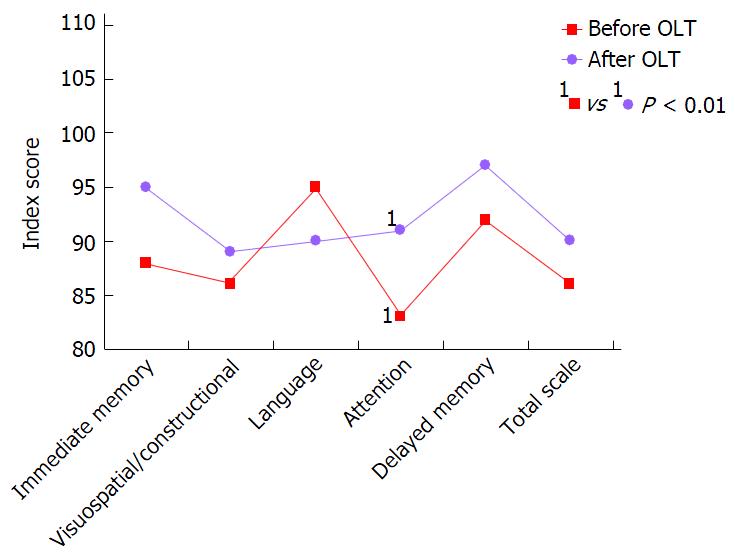

The patients not employed 12 mo after OLT showed a significant increase in the PHES (n = 26, P = 0.04) whereas the CFF (n = 23, P = 0.28) did not change significantly [before OLT PHES median -1.0, range 22 (min -18, max 4), CFF mean 41.0 Hz ± 4.4; after OLT PHES median -1.0, range 13 (min -9, max 4), CFF mean 41.9 Hz ± 4.1]. The RBANS domain score Attention increased significantly 12 mo after OLT (n = 23, P < 0.01, mean 82.9 ± 16.2 before OLT, 91.2 ± 15.6 after OLT) whereas all other RBANS domain scores did not change significantly (Figure 4).

Using binary logistic regression analysis (Method enter, Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients χ2 = 52.840, P < 0.001, -2 Log likelihood = 77.581, Nagelkerke R Square= 0.571, Cohen’s d = 0.70), employment status before OLT [Wald statistic = 21.5, P < 0.001, odds ratio (OR) = 19.64, confidence interval for OR 5.58 to 69.14] and age in years (Wald statistic = 8.17, P < 0.01, OR = 0.90, confidence interval for OR 0.84 to 0.97) were independent predictors of the employment status 12 mo after OLT (n = 95, n = 1 excluded due to missing value concerning profession). No significant effects were found for the underlying liver disease, history of HE before OLT, labMELD score, profession, sex, SF-36 sum score before OLT and neurological complications after OLT. In a subgroup of patients who filled in the SF-36 after transplantation (Method enter, Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients χ2 = 50.579, P < 0.001, -2 Log likelihood = 46.137, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.685 and Cohen’s d = 0.94, n = 71) the employment status before OLT (Wald statistic = 11.84, P < 0.001, OR = 20.13, confidence interval for OR = 3.64-111.27) and the SF-36 sum score after OLT (Wald statistic = 7.18, P < 0.01, OR for increment of 10 points = 1.10, confidence interval for OR = 1.03 -1.17) were independent predictors of the employment status after OLT.

This prospective study evaluated the impact of hepatic encephalopathy before OLT and neurological complications after OLT on the employment status 12 mo after liver transplantation. Moreover, health-related quality of life, age, sex, employment status before OLT and professional category were registered to identify factors which might be significantly associated with the employment status one year after OLT.

In contrast to our hypothesis, we did not find a significant impact of HE before or neurological complications after OLT on the employment status 12 mo after OLT, though the not employed patients after OLT showed a trend towards a higher frequency of HE before OLT and neurological complications after OLT in comparison to patients employed after OLT. Instead, the employment status after OLT was independently predicted by the employment status before OLT, age and health-related quality of life after OLT.

Hepatic encephalopathy is associated with high morbidity and has a direct impact on health-related quality of life before liver transplantation[26]. Impairment of motor and cognitive function lead to premature retirement of patients with HE[18]. Blue collar workers with liver cirrhosis are more frequently considered unfit for work than white collar workers, probably due to the fact that HE significantly affects motor function while language ability is preserved[18]. In accordance herewith, our patients who were not employed before OLT had more frequently a history of HE and had predominantly a vocational education for qualification compared to employed patients.

The credo that HE is completely reversible has been put into question recently, since it was shown that patients who had suffered HE before OLT, had an incomplete recovery of their cognitive function about 1 year afterwards[13,27,28]. This could well interfere with the patients’ working ability. However, we did not find a significant impact of a HE history upon the employment status after OLT in our patients. Instead, like others, we observed an improvement in cognitive function in our patients after OLT with only a few patients showing abnormal test results 12 mo after OLT, for example, in the PHES (9 of 73 examined; 12.3%)[13,27]. Of these, only one patient was employed whereas 8 patients were not employed. There was no relation to any specific underlying cause of liver disease, such as alcoholism.

Neurological complications affecting the CNS are frequent in the first weeks after OLT and are known to prolong the in-hospital stay[14,15]. Although the distinctive impairment of cognitive function by neurological complications in the first weeks after OLT might only be transient[17], long term impairment might occur and influence the working capability. Nevertheless, our results did not indicate that neurological complications significantly impair the working capability 1 year after OLT and thus underline the good prognosis of neurological complications in the first weeks after OLT as long as they are promptly diagnosed and treated sufficiently. Our results still showed a trend indicating a higher frequency of neurological complications after OLT in the group of patients not employed 12 mo after OLT.

Eighty point five percent (n = 33) of the surviving patients employed before OLT (n = 41) returned to work afterwards, indicating the importance of the pre transplant working status upon a patient’s occupational fate. This is in accordance with the findings of other studies[2-5,8,29] which came to similar results, irrespective of the country or continent where the study was performed[9].

It is no surprise that age was a predictor for post OLT employment status as well, since it may be hypothesized that younger patients have a higher physical and cognitive health resource than older patients, facilitating the return to work. Additionally, social insurance companies might be more eager to reintegrate young patients into work because of the costs of early retirement. Also, employers might have a higher confidence in young patients to be capable of working compared to older patients[8].

In our study, patients who were working 1 year after OLT had a significantly higher SF-36 and SF-6D score than those who did not, and the subgroup of patients that returned to their pre OLT job after transplantation had significantly better health related quality of life scores than patients who were employed before OLT but did not return to employment after OLT. Furthermore, the SF-36 score at 12 mo after OLT was an independent predictor for employment after OLT in the subgroup of patients who filled in this form. Aberg et al[2] assessed HRQoL in 354 patients after OLT [age at OLT (mean) 48 years, 42% male] compared to 6050 age and gender matched controls. They showed that the employed OLT patients had significantly higher HRQoL scores than retired patients and concluded that employment is an indicator of HRQoL. Our data do not allow a decision, whether the scores are higher due to the fact that the patients were able to return to a normal life and therefore perceived themselves as physically and mentally fit, or if better physical and mental condition facilitated the return to employment after OLT. However, it is conceivable that patients who have reached independence and the economic status they had before OLT have more confidence in their physical and cognitive functions than those who are not. In consequence, reintegration of patients after OLT into employment should be considered an important tool to achieve patients’ well-being. The significant difference between patients who are working and those who are not employed after OLT and additionally between the subgroup of patients that were employed before and after OLT compared to patients that did not return to employment after OLT with regard to cognitive function (RBANS) in this study, however, indicates that besides socio-economic factors also medical factors must be considered (Tables 3 and 5).

In contrast to some other studies[8,30] and in accordance with Hunt et al[31] we did not find a significant gender difference with regard to employment status after OLT. The differing results between the studies may be due to lacking comparability of the classification of “work” especially as not all studies classified “homemakers” as employed.

Education has also been reported to have an impact on employment after OLT[3,4]. Our results were not able to confirm this assumption probably due to the low number of patients with a university degree (21 of 96 survivors; 21.9%). Nevertheless, a trend (P = 0.06) towards a higher frequency of vocational training in the group of patients not employed after OLT was observed. But the effect of education on post OLT employment was not observed by all authors[31], and obviously it is not exclusively the level of education that affects the probability to return to work after OLT, but also the type of work done before OLT. Adams et al[32] as well as Weng et al[6] showed that patients working in non-office jobs were less likely to return after OLT than patients working in an office. This may be due to different physical demands[29]. However, considering the observation that blue collar workers with chronic liver disease are more often not employed than white collar workers might as well be just a sequel of the pre OLT health status.

Contradictory results have been achieved considering the effect of the underlying liver disease - especially alcoholism[7,8,33-35] and hepatitis C[3] - upon the proportion of subjects employed after OLT. Alcoholic liver disease was estimated to have no effect[33,34], to increase[7] or to decrease[8,35] the probability of resuming work after OLT. In our study the underlying liver disease had no effect on the employment status after OLT.

Patients with chronic liver disease are not employed before OLT due to various reasons. Cirrhosis-associated morbidity might be the most frequent because being frequently certified unfit for work might lead to unemployment and employers as well as social insurance companies might aspire the patients’ retirement. This assumption includes the hypothesis that patients staying employed before OLT might be less impaired and might have a shorter period of time of severe liver disease. It might alleviate returning to work after OLT and achieving the economic status as well as the financial independence they had before OLT. The employer might be more eager to reintegrate these patients after OLT because the circumstances signal that work capability exists. Still, our data do not support this assumption, if the labMELD score is considered representative for patients’ health status.

Although patients who were not employed after OLT differed with regard to psychometric test results from those who were employed, the majority of the not employed patients achieved results within the normal range. The PHES, for example, was only abnormal in 8 of 43 patients (18.6%). Resuming work after OLT for patients who were not employed before OLT seems quite unlikely as only 10 (18.2%) of the not employed patients of our cohort returned to work after OLT. Similar results were described in other studies[9]. Probably the time off work is too long, determining low confidence in patients and employers that reintegration is possible. Furthermore, bureaucracy and fear of losing pension claims might play a role. Additionally, our data (Tables 3-6) and that of others[9] indicate that returning to the pre OLT job might be impaired by poor physical or impaired mental functioning. Achieving an occupational retraining, however, is extensive and support for patients might be low. To solve these problems, interventions based on the individual needs and obstacles of each single patient are needed to facilitate reemployment after OLT. Although so far data about the efficiency of interventions before and after OLT to facilitate reemployment after OLT are missing, the main aim seems to be to keep the patients with chronic liver disease employed before OLT[36]. To achieve this aim, liver related complications like hepatic encephalopathy and ascites need to be prevented or if applicable treated as soon as possible. The patients’ mobility might be maintained by regular physiotherapy. Furthermore, education programs for employers about working capabilities of patients with chronic liver disease might prevent loss of employment before OLT. Such interventions might also increase the health related quality of life. After OLT, rehabilitation programs that focus on the individual physical and mental job requirements for each patient might be conducive to reintegrate the patient into the pre OLT job and to increase the health related quality of life. In addition, employers need to be educated about the working capabilities of patients after OLT. If the reintegration into the pre OLT job is not possible, collaboration with social workers and employment support agencies might be needed to match the patient to an appropriate alternative job. In this respect, the reduction of bureaucratic barriers seems to be particularly important concerning the encouragement of patients to resume work after OLT while at the same time, if needed, providing them with full medical coverage[36].

Limitations of our study are that our results can only be compared to studies that also classified “homemakers” and “students” as employed, because some studies only classified subjects as employed if they were working for a wage. Furthermore, 46 patients (40.4%) were included after OLT. Data for the psychometric tests and quality of life scores before OLT were missing for these patients. However, all other variables were available because all patients included underwent neurological examination after OLT and detailed case records were available for all patients including the HE history, occupation, underlying liver disease, labMELD score and medication. Finally, our results are only based on patients within the German health-care system, which might limit the transferability to other countries. Nevertheless, our findings are well in line with those of former studies, indicating the effect of the pre transplant employment status upon the post transplant working career, independent of the different health care systems.

As a result, our data confirm that employment status before OLT is most important in predicting the employment status 12 mo after OLT. Neither prior-OLT HE nor neurological complications after OLT are independent risk factors for unemployment 1 year after OLT. However, our results show a trend for both values to be more frequent in patients not employed after OLT, indicating the need to analyse a larger sample to finally answer the question if HE before OLT and neurological complications after OLT affect working ability after transplantation.

In conclusion, education of patients, employers and social insurance companies is needed to emphasise that it is worth analysing, on a single subject basis, if a patient is capable of being reintegrated into work after OLT. Obstacles should be identified in every single case because resuming work after OLT might improve the post OLT care and increase the health-related quality of life in patients after OLT.

The authors would like to thank Andreas Manthey for language editing the manuscript and Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Hartmut Hecker for reviewing the statistical methods of this study.

Specialized transplantation centres and improvement of immunosuppressive therapy have significantly increased survival rates after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). Thus, besides mortality other indicators of treatment quality emerged. Employment after OLT is considered to indicate treatment quality and socio-economic factors before OLT are esteemed crucial in this respect. However, currently only about 50% of patients are reintegrated into employment after OLT and the reasons for not returning to the pre OLT job are not well described. The relevance of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) before OLT and neurological complications after OLT has not been considered so far although both can significantly impact patients’ physical and mental ability before and after OLT. This prospective study was designed to evaluate the impact of HE before and neurological complications after OLT in addition to socio-economic factors upon the employment status 1 year after OLT.

Outcome of patients after OLT improved during the last 35 years and thus the focus on the patients’ mental and physical well-being after OLT increased. Especially reintegration into employment was identified as an important factor as it is important for the physical and mental health after OLT. However, only about 50% of the patients return to their jobs after OLT. This study contributed to this research field by evaluating whether hepatic encephalopathy before OLT or neurological complications after OLT have an impact on the employment status of the patients 1 year after OLT.

The available studies identified employment before OLT, the type of employment and younger age as the main predicting factors for reintegration into employment after OLT. This study contributed by showing that neither prior-OLT hepatic encephalopathy nor neurological complications after OLT are independent risk factors for unemployment 1 year after OLT. Furthermore, their study confirmed that employment status before OLT is most important in predicting the employment status 12 mo after OLT.

This study showed that neither hepatic encephalopathy before OLT nor neurological complications after OLT increase the probability of unemployment one year after OLT. Especially employment before OLT predicts the reintegration into employment after OLT and thus interventions should focus on how to keep patients with liver cirrhosis employed before OLT. Furthermore interventions are needed during the rehabilitation after OLT that focus on the physical and mental needs required for the pre OLT job of each patient.

Hepatic encephalopathy: A frequent complication of liver cirrhosis caused by liver insufficiency and porto-systemic shunts. It is based on neurochemical and neurophysiological disorders of the brain and ammonia is believed to be of major importance. It is characterized by deficits in motor accuracy and motor speed as well as cognitive impairment especially concerning attention, whereas verbal abilities maintain unaffected. Neurological complications: encephalopathy, seizures, tremor, psychotic disorders and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome occur in about 30% of the patients after OLT.

In this well-written article, Pflugrad et al explore factors associated with employment after OLT, which is essential for quality of life and meaningful transplant outcomes. They found that hepatic encephalopathy before or central nervous system complications after OLT were not independent predictors of employment, unlike pre-OLT employment, age and post-OLT functional status.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Farmakiotis D S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Strassburg CP, Manns MP. [Liver transplantation: indications and results]. Internist (Berl). 2009;50:550-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aberg F, Rissanen AM, Sintonen H, Roine RP, Höckerstedt K, Isoniemi H. Health-related quality of life and employment status of liver transplant patients. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:64-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sahota A, Zaghla H, Adkins R, Ramji A, Lewis S, Moser J, Sher LS, Fong TL. Predictors of employment after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:490-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moyzes D, Walter M, Rose M, Neuhaus P, Klapp BF. Return to work 5 years after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2878-2880. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Rongey C, Bambha K, Vanness D, Pedersen RA, Malinchoc M, Therneau TM, Dickson ER, Kim WR. Employment and health insurance in long-term liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1901-1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Weng LC, Chen HC, Huang HL, Wang YW, Lee WC. Change in the type of work of postoperative liver transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:544-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aberg F, Höckerstedt K, Roine RP, Sintonen H, Isoniemi H. Influence of liver-disease etiology on long-term quality of life and employment after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:729-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huda A, Newcomer R, Harrington C, Blegen MG, Keeffe EB. High rate of unemployment after liver transplantation: analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:89-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huda A, Newcomer R, Harrington C, Keeffe EB, Esquivel CO. Employment after liver transplantation: a review. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:233-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, Wong P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in RCA: 1409] [Article Influence: 128.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Grover VP, Tognarelli JM, Massie N, Crossey MM, Cook NA, Taylor-Robinson SD. The why and wherefore of hepatic encephalopathy. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:381-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, Rückert N, Hecker H. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34:768-773. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Campagna F, Montagnese S, Schiff S, Biancardi A, Mapelli D, Angeli P, Poci C, Cillo U, Merkel C, Gatta A. Cognitive impairment and electroencephalographic alterations before and after liver transplantation: what is reversible? Liver Transpl. 2014;20:977-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Colombari RC, de Ataíde EC, Udo EY, Falcão AL, Martins LC, Boin IF. Neurological complications prevalence and long-term survival after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:1126-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bernhardt M, Pflugrad H, Goldbecker A, Barg-Hock H, Knitsch W, Klempnauer J, Strassburg CP, Hecker H, Weissenborn K, Tryc AB. Central nervous system complications after liver transplantation: common but mostly transient phenomena. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:224-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Umapathy S, Dhiman RK, Grover S, Duseja A, Chawla YK. Persistence of cognitive impairment after resolution of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1011-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Saner FH, Nadalin S, Radtke A, Sotiropoulos GC, Kaiser GM, Paul A. Liver transplantation and neurological side effects. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schomerus H, Hamster W. Quality of life in cirrhotics with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2001;16:37-41. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Schomerus H, Weissenborn K, Hecker H, Hamster W, Rückert N. PSE-Syndrom-Test, Psychodiagnostisches Verfahren zur quantitativen Erfassung der (minimalen) portosystemischen Enzephalopathie (PSE). Swets Test Services, Swets and Zeitlinger BV, Frankfurt. 1999;. |

| 20. | Romero-Gómez M, Córdoba J, Jover R, del Olmo JA, Ramírez M, Rey R, de Madaria E, Montoliu C, Nuñez D, Flavia M. Value of the critical flicker frequency in patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:879-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Weissenborn K. Psychometric tests for diagnosing minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:227-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Goldbecker A, Weissenborn K, Hamidi Shahrezaei G, Afshar K, Rümke S, Barg-Hock H, Strassburg CP, Hecker H, Tryc AB. Comparison of the most favoured methods for the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy in liver transplantation candidates. Gut. 2013;62:1497-1504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bullinger M. Assessment of health related quality of life with the SF-36 Health Survey. Die Rehab. 1996;35:17-27; quiz 27-29. |

| 24. | Kharroubi SA, Brazier JE, Roberts J, O‘Hagan A. Modelling SF-6D health state preference data using a nonparametric Bayesian method. J Health Econ. 2007;26:597-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Conn HO, Leevy CM, Vlahcevic ZR, Rodgers JB, Maddrey WC, Seeff L, Levy LL. Comparison of lactulose and neomycin in the treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy. A double blind controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:573-583. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Orr JG, Homer T, Ternent L, Newton J, McNeil CJ, Hudson M, Jones DE. Health related quality of life in people with advanced chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1158-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Garcia-Martinez R, Rovira A, Alonso J, Jacas C, Simón-Talero M, Chavarria L, Vargas V, Córdoba J. Hepatic encephalopathy is associated with posttransplant cognitive function and brain volume. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:38-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lewis MB, Howdle PD. Cognitive dysfunction and health-related quality of life in long-term liver transplant survivors. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1145-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Saab S, Wiese C, Ibrahim AB, Peralta L, Durazo F, Han S, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, Ghobrial RM, Goldstein LI. Employment and quality of life in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1330-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cowling T, Jennings LW, Goldstein RM, Sanchez EQ, Chinnakotla S, Klintmalm GB, Levy MF. Liver transplantation and health-related quality of life: scoring differences between men and women. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:88-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hunt CM, Tart JS, Dowdy E, Bute BP, Williams DM, Clavien PA. Effect of orthotopic liver transplantation on employment and health status. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:148-153. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Adams PC, Ghent CN, Grant DR, Wall WJ. Employment after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1995;21:140-144. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Newton SE. Work outcomes for female liver transplant recipients with alcohol-related liver disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2001;24:288-293. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Cowling T, Jennings LW, Goldstein RM, Sanchez EQ, Chinnakotla S, Klintmalm GB, Levy MF. Societal reintegration after liver transplantation: findings in alcohol-related and non-alcohol-related transplant recipients. Ann Surg. 2004;239:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Pageaux GP, Michel J, Coste V, Perney P, Possoz P, Perrigault PF, Navarro F, Fabre JM, Domergue J, Blanc P. Alcoholic cirrhosis is a good indication for liver transplantation, even for cases of recidivism. Gut. 1999;45:421-426. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Åberg F. From prolonging life to prolonging working life: Tackling unemployment among liver-transplant recipients. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3701-3711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |