Published online Feb 8, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i4.226

Peer-review started: November 3, 2015

First decision: December 4, 2015

Revised: December 17, 2015

Accepted: January 16, 2016

Article in press: January 19, 2016

Published online: February 8, 2016

Processing time: 84 Days and 13.5 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the outcomes of two-stage liver transplant at a single institution, between 1993 and March 2015.

METHODS: We reviewed our institutional experience with emergency hepatectomy followed by transplantation for fulminant liver failure over a twenty-year period. A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained liver transplant database was undertaken at a national liver transplant centre. Demographic data, clinical presentation, preoperative investigations, cardiocirculatory parameters, operative and postoperative data were recorded.

RESULTS: In the study period, six two-stage liver transplants were undertaken. Indications for transplantation included acute paracetamol poisoning (n = 3), fulminant hepatitis A (n = 1), trauma (n = 1) and exertional heat stroke (n = 1). Anhepatic time ranged from 330 to 2640 min. All patients demonstrated systemic inflammatory response syndrome in the first post-operative week and the incidence of sepsis was high at 50%. There was one mortality, secondary to cardiac arrest 12 h following re-perfusion. Two patients required re-transplantation secondary to arterial thrombosis. At a median follow-up of 112 mo, 5 of 6 patients are alive and without evidence of graft dysfunciton.

CONCLUSION: Two-stage liver transplantation represents a safe and potentially life-saving treatment for carefully selected exceptional cases of fulminant hepatic failure.

Core tip: We share our experience with selected cases of emergency total hepatectomy followed by liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure. This involves initial haemodynamic stabilization by recipient hepatectomy, creating a temporary porto-caval shunt to permit venous drainage during a variable anhepatic phase, then orthotopic transplantation once a suitable donor graft is available.

- Citation: Sanabria Mateos R, Hogan NM, Dorcaratto D, Heneghan H, Udupa V, Maguire D, Geoghegan J, Hoti E. Total hepatectomy and liver transplantation as a two-stage procedure for fulminant hepatic failure: A safe procedure in exceptional circumstances. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(4): 226-230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i4/226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i4.226

Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for acute or chronic end-stage liver disease. In cases of acute liver failure, often the only life-saving intervention is a super-urgent liver transplantation. However, immediate allocation of a donor organ is not always achievable. Without urgent hepatectomy, some patients with fulminant hepatic failure develop a toxic hepatic syndrome with potentially catastrophic haemorrhage[1]. Toxic liver syndrome is defined as complete liver necrosis associated with critical multi-organ dysfunction[2]. In this grave circumstance, these critically-ill patients may benefit from a two-stage approach to transplantation; with urgent explantation of the toxic liver and creation of a temporary portocaval shunt, followed by transplantation as soon as a donor organ becomes available[2]. First reported in 1988 by Ringe et al[2] for a patient with primary graft failure causing multi-organ dysfunction, the goal of the first stage of this technique is haemodynamic and metabolic stabilisation. Subsequent to Ringe’s description of this novel approach to retransplantation for primary graft failure, a wider variety of indications for this technique have been sporadically reported including liver trauma, spontaneous hepatic rupture, haemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelet syndrome associated with preeclampsia, and acute deterioration of chronic liver disease[2-11]. During the first stage of these two-stage transplantations, the inferior vena cava is retained and a porto-caval anastomosis allows systemic and portal venous drainage during the subsequent anhepatic period[2-11]. Once an allograft becomes available, the second stage involves orthotopic liver transplantation using a modified piggyback technique without venovenous bypass[2-11].

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database was undertaken to identify all patients who underwent two-stage liver transplantation at a single institution (a National Liver Transplant Unit) between January 1993 and March 2015. Demographic data, clinical presentation, preoperative investigations, operative details, postoperative course, and histopathological results were recorded. Data collection and analyses were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 16.0) (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the variables’ distribution. For nonparametric data, continuous variables are presented as median values (and range) and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for any two sample comparisons. Dichotomous variables were compared using the χ2 test. All tests were two tailed and results with a P-value of < 0.05 were considered statistical significant.

During the study period, six cases of two-stage liver transplantation were undertaken in our centre. There was a male preponderance (4 males, 2 females). Median age at presentation was 28 years (range 20-47). Two patients had a past medical history of depression, no other co-morbidities were present. The most common indication for super-urgent transplantation was extensive liver necrosis secondary to paracetamol overdose (n = 3). One patient developed fulminant liver failure secondary to Hepatitis A infection. One patient had extensive haemorrhage secondary to liver trauma, and one patient developed exertional heat stroke causing ischemic hepatitis while running the final stages of an ultra-marathon. Five of six patients had evidence of toxic liver syndrome, as previously defined. The median model end stage liver disease was 39.50 (range 28-40). All patients had hypoglycemia and metabolic acidosis. In 50% of these cases, haemofiltration was initiated prior to hepatectomy, and all patients were intubated and mechanically ventilated before the procedure. The liver trauma case was the only patient who did not demonstrate signs of encephalopathy. Features of cerebral edema were present in 50% of cases. The anhepatic time ranged from 330 and 2640 min. In two patients, the hepatectomy was performed when a donor graft had been accepted for harvest but was not yet available. In one case, the hepatectomy was undertaken prior to acceptance of a donor organ due to uncontrollable haemorrhage in the recipient and the patient was listed as “super-urgent” for transplantation. For the remaining three patients the hepatectomy was performed at the time of listing the patinet for superurgent transplantation (Table 1).

| Sex, age | Indication | MELD | Toxic liver syndrome | CVVH | Hptc before graft availability | Inotrope requirements | Anhepatic phase (h) | Survival (mo) | |

| 1 | F, 26 | Paracetamol overdose | 39 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7 | 116 |

| 2 | M, 41 | Heat stroke | 40 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 16 | 22 |

| 3 | M, 47 | Fulminant hepatits A | 40 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 5.5 | 12 h |

| 4 | M, 20 | Paracetamol overdose | 40 | Yes | No | No | No | 5.8 | 107 |

| 5 | F, 30 | Paracetamol overdose | 36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 44 | 108 |

| 6 | M, 21 | Liver trauma | 28 | No | No | Yes | No | 15 | 106 |

All patients underwent total hepatectomy and end-to side portocaval anastomosis with temporary abdominal closure as the first of a two-stage transplantation. During the anhepatic phase, patients were managed in the intensive care unit and received haemofiltration with plasma separation treatment. Orthotopic liver transplantation was then performed as soon as an allograft became available. In all cases, histological evaluation of the native liver confirmed the indication for emergency liver transplantation (total liver necrosis regardless the etiology). The use of noradrenaline was required in 4 patients before total hepatectomy with a median of 67 μg/min (range 50-200). During the anhepatic period the inotropic requirements increased to 74 μg/min (10-120), however inotropic requirements decreased immediately after reperfusion of the donor grafts, with a median noradrenaline requirement of 26 μg/min (range 5-60).

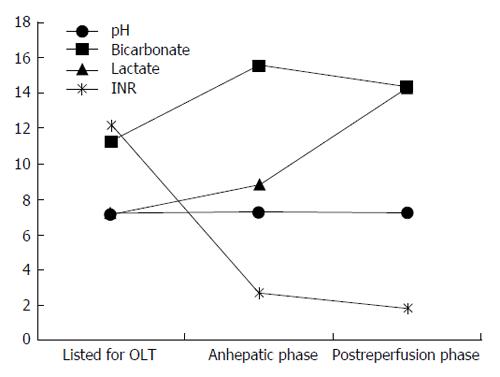

Arterial blood gasometry parameters demonstrated increased levels of lactate during the anhepatic phase from a median of 7.2 mmol/L pre-hepatectomy to 8.8 mmol/L. However their acidosis improved during the anhepatic phase as reflected by an increase in pH from median of 7.14 to 7.25, and an increase in bicarbonate from 11.3 to 15.6 mmol/L (Figure 1). Coagulation parameters pre-hepatectomy, during the anhepatic phase, and post transplant are shown in Table 2. During graft implantation, median blood loss was 8.5 L (range 2.5-43 L). All patients received transfusion of blood products, pools of platelets (median of 4 pools), plasma products (median of 9.5 units) and packed red cells (median 8.5 units). During the anhepatic phase, three patient developed ventricular tachycardia which was treated with amiodarone infusion. One patient (liver trauma case) required repeated cardioversions during the anhepatic phase as well as after reperfusion of the donor graft.

| No. of patient | Dose NA | pH | Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | Lactate (mmol/L) | INR | Sodium (mmol/L) | Potasium (mmol/L) | |

| Before Hptc | 70 | 7.14 | 11.30 | 5.32 | 11.25 | 133 | 3.9 | |

| 1 | Anhepatic | 80 | 7.24 | 17.20 | 7.3 | 2.50 | 133 | 3.7 |

| Post reperfusion | 60 | 7.27 | 16.40 | 6 | 1.85 | 135 | 5.4 | |

| Before Hptc | 64 | 7.15 | 13.30 | 9.20 | 15.80 | 136 | 5.5 | |

| 2 | Anhepatic | 80 | 7.26 | 14.00 | 11 | 3.33 | 137 | 4.5 |

| Post reperfusion | 20 | 7.20 | 14.60 | 10 | 2.27 | 145 | 3.9 | |

| Before Hptc | 50 | 7.06 | 14.70 | 10.20 | 13 | 138 | 4.8 | |

| 3 | Anhepatic | 36 | 7.17 | 13.30 | 10 | 1.75 | 143 | 4.9 |

| Post reperfusion | 48 | 7.12 | 13.80 | 10.5 | 1.75 | 146 | 5.0 | |

| Before Hptc | None | 7.34 | 11.10 | 5.30 | 17 | 133 | 3.6 | |

| 4 | Anhepatic | 10 | 7.34 | 20.70 | 4.20 | 2.90 | 133 | 3.6 |

| Post reperfusion | 5 | 7.32 | 18.60 | 3.7 | 1.64 | 136 | 3.8 | |

| Before Hptc | 200 | 7.16 | 11.30 | 12.00 | 6.3 | 148 | 3.7 | |

| 5 | Anhepatic | 68 | 7.26 | 18.00 | 12.30 | 3.01 | 141 | 4.2 |

| Post reperfusion | 32 | 7.19 | 14.00 | 6.7 | 2.47 | 144 | 5.20 | |

| Before Hptc | None | 7.02 | 10.70 | 3.30 | 10.59 | 151 | 5.0 | |

| 6 | Anhepatic | 120 | 6.91 | 13.50 | 7.7 | 2.46 | 146 | 4.3 |

| Post reperfusion | 10 | 7.01 | 12.70 | 7.7 | 1.61 | 144 | 3.8 | |

| Before Hptc | 67 | 7.14 | 11.3 | 7.26 | 12.12 | 137 | 4.35 | |

| (50-200) | (7.02-7.34) | (10.70-14.7) | (3.3-12) | (6.3-17) | (133-152) | (3.6-5.5) | ||

| Median | Anhepatic | 74 | 7.25 | 15.6 | 8.85 | 2.7 | 139 | 4.3 |

| range | (10-120) | (6.91-7.34) | (13.30-20.70) | (4.2-12.3) | (1.75-3.33) | (133-146) | (3.6-4.9) | |

| Post reperfusion | 26 | 7.19 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 1.8 | 144 | 4.45 | |

| (5-60) | (7.01-7.32) | (12.7-18.60) | (12.7-18.60) | (1.61-2.47) | (135-146) | (3.8-5.4) |

All patients (n = 6) fulfilled criteria for the diagnosis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome in the first post-transplant week, with 50% having a source of sepsis identified which required anti-microbial treatment with a single broad-spectrum agent. The median time to extubation was 7 d (range 5-15), haemodialysis duration was 20 d (range 6-28) and median hospital stay was 33 d (range 2-210). Two patients required re-transplantation secondary to arterial thrombosis (33%). One of these patients necessitated right hemicolectomy secondary to ileocolic arterial ischemia as well as the early hepatic artery thrombosis which required re-transplantation. There was a single mortality which was due to cardiac arrest and occurred 12 h after reperfusion of the graft, with a median follow-up of 112 mo.

Acute liver failure is a rapidly devastating pathology due to its potential to precipitate multi-organ failure, sepsis and cerebral oedema. Despite advances in supportive care, liver transplantation remains the only potentially life-saving treatment. Although fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) in not a common indication for orthotopic liver transplantation, these patients nonetheless represent a significant challenge for transplant surgeons. Data suggests that the most important prognostic indicators for patients with FHF undergoing transplantation are the degree of encephalopathy, patient’s age, the etiology of FHF, and the time to transplantation with the majority of authors concurring that transplantation within 48-72 h is critical to reduce mortality[1].

The anhepatic state requires considerable expertise in critical care to manage these gravely ill patients. In addition to cardiorespiratory support, haemofiltration and plasma separation are essential to prevent the development of severe lactate acidosis. The longest anhepatic period compatible with life is reported to be 66 h, which was recorded in a child with liver graft non-function after transplantation[12]. Herein we report a maximum anhepatic time of 44 h, in a patient who survived despite requiring re-transplantation secondary to hepatic artery thrombosis.

The number of cases of two-stage transplantation reported in the literature is scant and therefore survival rates vary widely[2-11]. However, advances in surgical techniques and supportive care appear to have exerted a beneficial effect on survival over time. In his seminal work almost two decades ago, Ringe et al[2,3] reported 32 patients treated with two-stage transplantation with 24 mortalities (75% mortality). In 2001, Domínguez Fernández et al[7] reported their outcomes from a series of eight patients who underwent emergency hepatectomy for FHF. Two patients died before a donor liver became available. A further five of six patients who underwent transplantation after an anhepatic period died postoperatively secondary to primary nonfunction or sepsis causing multiorgan failure (87.5% mortality). Herein, we report a series of six patients with a single death (16.6% mortality).

In conclusion, we report a series of cases of two-stage liver transplantation, which is a potentially life-saving procedure in carefully selected patients in exceptional clinical circumstances.

In the setting of fulminant liver failure, immediate donor graft allocation for life-saving transplant may not always be possible and a two-stage approach may be necessary. This involves initial haemodynamic stabilisation by recipient hepatectomy - creating a temporary porto-caval shunt to allow circulation during a variable anhepatic phase. Once an allograft becomes available, orthotopic transplantation is undertaken using the standard technique. In this study, the authors evaluated the outcomes of two-stage liver transplant at a single institution, between 1993 and March 2015.

In cases of acute liver failure, the only life-saving procedure is frequently an emergency liver transplantation. However, immediate allocation of a donor organ is not always possible, particularly in the acute setting. Without urgent removal of the native liver, patients with fulminant hepatic failure, regardless of aetiology, can develop a life-threatening toxic hepatic syndrome. The results of this study suggest that in carefully selected patients a two-stage approach to super-urgent liver transplantation has utility, and can salvage these patients from the multi-organ failure arising from a toxic liver.

In this study, two-stage liver transplantation appears to be a valuable, albeit exceptional, approach to the management of fulminant liver failure with associated toxic liver syndrome. The authors report a series of six patients treated with emergency hepatectomy and temporary portocaval shunt, followed by urgent orthotopic liver transplantation once a suitable donor graft became available. There was a single perioperative mortality in this series. Although two of the surviving five patients subsequently required re-transplantation for hepatic artery thrombosis, all are alive and without evidence of current graft dysfunction at a median follow-up of 112 mo. The number of cases of two-stage transplantation reported in the literature is scant, therefore mortality and morbidity rates are largely unknown. This report contributes such data to the transplant literature.

This study suggests that two-stage liver transplantation is a potentially life-saving procedure in carefully selected patients and in exceptional clinical circumstances.

Toxic liver syndrome: A critical systemic inflammatory syndrome-like response defined as complete liver necrosis associated with critical multi-organ dysfuntion. Two-stage liver transplantation: A procedure which involves emergency hepatectomy and end-to-side portocaval anastmosis in the first stage, followed by liver transplantation when a donor organ becomes available in the second stage.

The authors of this paper evaluated the outcomes of two-stage liver transplantation as an exceptional procedure in carefully selected patients with fulminant hepatic failure. Further reports of such cases are necessary to better evaluate its safety and utility in the management of acute liver failure.

P- Reviewer: Ferraioli G, He ST, Savopoulos CG S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Gotthardt D, Riediger C, Weiss KH, Encke J, Schemmer P, Schmidt J, Sauer P. Fulminant hepatic failure: etiology and indications for liver transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22 Suppl 8:viii5-viii8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ringe B, Pichlmayr R, Lübbe N, Bornscheuer A, Kuse E. Total hepatectomy as temporary approach to acute hepatic or primary graft failure. Transplant Proc. 1988;20:552-557. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ringe B, Lübbe N, Kuse E, Frei U, Pichlmayr R. Total hepatectomy and liver transplantation as two-stage procedure. Ann Surg. 1993;218:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rozga J, Podesta L, LePage E, Hoffman A, Morsiani E, Sher L, Woolf GM, Makowka L, Demetriou AA. Control of cerebral oedema by total hepatectomy and extracorporeal liver support in fulminant hepatic failure. Lancet. 1993;342:898-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | So SK, Barteau JA, Perdrizet GA, Marsh JW. Successful retransplantation after a 48-hour anhepatic state. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:1962-1963. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Oldhafer KJ, Bornscheuer A, Frühauf NR, Frerker MK, Schlitt HJ, Ringe B, Raab R, Pichlmayr R. Rescue hepatectomy for initial graft non-function after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;67:1024-1028. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Domínguez Fernández E, Lange K, Lange R, Eigler FW. Relevance of two-stage total hepatectomy and liver transplantation in acute liver failure and severe liver trauma. Transpl Int. 2001;14:184-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Erhard J, Lange R, Niebel W, Scherer R, Kox WJ, Philipp T, Eigler FW. Acute liver necrosis in the HELLP syndrome: successful outcome after orthotopic liver transplantation. A case report. Transpl Int. 1993;6:179-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chiumello D, Gatti S, Caspani L, Savioli M, Fassati R, Gattinoni L. A blunt complex abdominal trauma: total hepatectomy and liver transplantation. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:89-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Heneghan HM, Nazirawan F, Dorcaratto D, Fiore B, Boylan JF, Maguire D, Hoti E. Extreme heatstroke causing fulminant hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:2430-2432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Guirl MJ, Michael J, Weinstein JS, Goldstein RM, Levy MF, Klintmalm GB. “Two-stage total hepatectomy and liver transplantation for acute deterioration of chronic liver disease: A new bridge to transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:564-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hammer GB, So SK, Al-Uzri A, Conley SB, Concepcion W, Cox KL, Berquist WE, Esquivel CO. Continuous venovenous hemofiltration with dialysis in combination with total hepatectomy and portocaval shunting. Bridge to liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;62:130-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |