Published online Nov 18, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i32.1414

Peer-review started: March 2, 2016

First decision: March 22, 2016

Revised: September 13, 2016

Accepted: October 5, 2016

Article in press: October 9, 2016

Published online: November 18, 2016

Processing time: 259 Days and 12 Hours

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is one of the systemic vasculitis that affects the media wall of arteries of small and medium diameter. Diagnosis proves difficult due to the unspecific symptoms that dominate the clinical profile. Liver involvement is very diverse, ranging from the development of cirrhotic liver disease to acute abdomen presentation that requires surgery because of liver rupture. The management of these patients requires an expert multidisciplinary team. There are several cases in the literature that describe a sudden liver rupture as the first manifestation of a PAN. In this paper we present the case of a 75 years old patient without any previous disease, who is subjected to major hepatic resection for spontaneous liver rupture.

Core tip: Spontaneous liver rupture is a rare entity with very few cases in the literature reviewed; even when it has an autoimmune disease such etiology and with no previous trauma. We present our experience managing an urgent abdominal hemorrhage caused by a liver rupture as a first manifestation of Polyarteritis in a 75-year-old woman.

- Citation: Gómez-Luque I, Alconchel F, Ciria R, Ayllón MD, Luque A, Sánchez M, López-Cillero P, Briceño J. Spontaneous liver rupture as first sign of polyarteritis nodosa. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(32): 1414-1418

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i32/1414.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i32.1414

The first International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference of Rheumatological Diseases defined polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) as a systemic necrotizing vasculitis of arterial tunica media of small and medium sized arteries without the presence of any glomerulonephritis or vasculitis in arterioles, venules and capillaries or without association with anti-cytoplasmic neutrophil antibodies positivity[1].

PAN is a common systemic vasculitis generally involving several organs such as kidneys, skin, central and peripheral nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. The certain diagnosis is a complex task because of nonspecific laboratory tests and clinical features; therefore it must be based on histopathological analysis by biopsies.

The “American College of Rheumatology: Defined the criteria for the diagnosis of PAN in 1990[2]. To diagnose a PAN the patient must have 3 characteristics out of a list of 10 features, estimating a diagnostic sensitivity of 82.2% with a specificity of 86.6% (Table 1).

| Criteria diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa | |

| Weight loss | Loss of 4 kg or more of body weight since illness began, not due to dieting or other factors |

| Livedo reticularis | Mottled reticular pattern over the skin or portions of the extremities or torso |

| Testicular pain or tenderness | Pain or tenderness of the testicles, not due to infection, trauma, or other causes |

| Myalgias, weakness or leg tenderness | Diffuse myalgias (excluding shoulder and hip girdle) |

| Mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy | Development of mononeuropathy, multiple mononeuropathys, or polyneuropathy |

| Diastolic BP > 90 mmHg | Development of hypertension with diastolic BP higher than 90 mmHg |

| Elevated BUN or creatinine | Elevation of BUN > 40 mg/dL or creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL, not due to dehydration or obstruction |

| Hepatitis B virus | Presence of hepatitis B surface antigen or antibody in serum |

| Ateriographic abnormality | Arteriogrm showing aneurysms or occlusions of the visceral arteries, not due to arteriosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasa, or other noninflammatory causes |

| Biopsy of small or medium-sized artery containing PMN | Histologic changes showing the presence of granulocytes or granulocytes and mononuclear leukocytes in the artery wall |

Liver involvement in this disease is uncommon and difficult to diagnose. Hepatomegaly (21%), jaundice (12%) and alteration of biochemical liver-function markers (6%) have been reported in the literature in different publications[3]. The development of this type of autoimmune disease has been associated to positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), although the exact etiology is unclear. It is reported that HBsAg positive patients may have a better response to treatment and therefore better prognosis[4]. In addition, PAN may cause aneurysm development due to fibrotic arterial lumen occlusion and necrosis, including organs such as liver, spleen and kidneys. These may derive in chronic abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, stroke, intestinal perforation and even pancreatitis. In some cases infarction and hemorrhage may occur, causing hemoperitoneum bearing a poor prognosis.

Very few cases have been published to date in which spontaneous hepatic rupture would be the first clinical manifestation; even when it has an autoimmune disease such etiology and with no previous trauma.

We present our experience managing an urgent abdominal hemorrhage caused by a liver rupture as a first manifestation of PAN in a 75-year-old woman.

A 75-year-old woman with no previous medical history except chronic anemia and well-controlled arterial hypertension with outpatient follow-up. She is referred for transfusion from another hospital because of a severe anemia. The patient reported feeling general malaise with unmeasured fever several days before. No nausea or gastrointestinal symptoms were noted.

On examination the patient’s blood pressure was near the low end of normality without tachycardia. There was no neurological deficit, paraesthesia or loss of motor reflexes. The abdomen palpation proved pain predominantly in right quadrants, with some upper quadrant abdominal defense.

Blood tests found hemoglobin 6.7 g/dL with a hematocrit of 19.2% and white blood cell count of 18000 mm3 (neutrophilia 70%). Coagulation tests showed an INR of 1.34 with a prothrombin activity of 54%. Liver function enzymes showed altered cytolysis enzymes (AST/ALT: 273/275 U/L) and cholestatic enzymes (GGT/FA: 90/159 U/L); bilirubin was within normal range. Other inflammatory parameters reflected reactive-C protein of 227.5 mg/dL.

With this scenario an abdominal computed tomography scan was performed (Figure 1) where liver damage was reported in the form of a right hepatic lobe lesion with poorly defined and confluent contours, heterogeneous density and hypodense predominance. There was also a heterogeneous subcapsular and subhepatic collection, with some hyperdense areas that could be a hematoma, along with a moderate amount of intraabdominal free fluid.

In this context an exploratory laparotomy was performed. There was a bleeding liver injury involving the inferior segments of the right hepatic lobe (segments V-VI), the source of this bleeding was difficult to identify. Hemoperitoneum was present in all abdominal quadrants. An urgent right hepatectomy was executed. The patient received four red cell concentrates in the perioperative care and no vasoactive drugs were necessary.

The postoperative was otherwise uneventful with only a persistent leukocytosis outstanding, without any other signs of sepsis. White blood cell count was normal at the time of discharge.

The pathology report described the existence of an inflammatory and haemorrhagic abscess with a volume of 10 cm × 7 cm × 2 cm as the cause of the hemoperitoneum. The remaining liver parenchyma appeared normal.

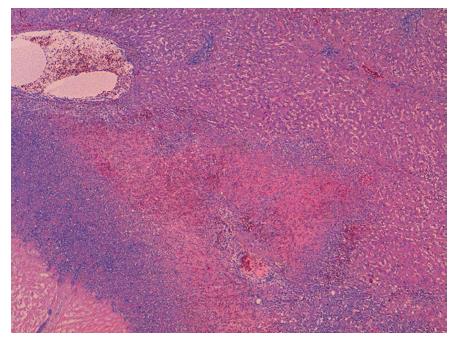

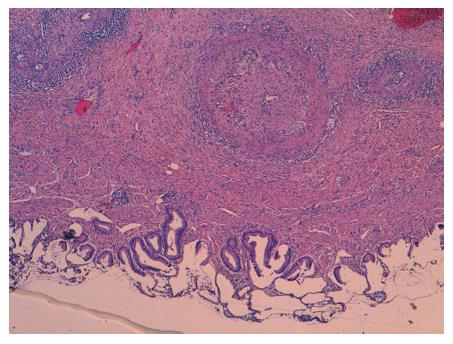

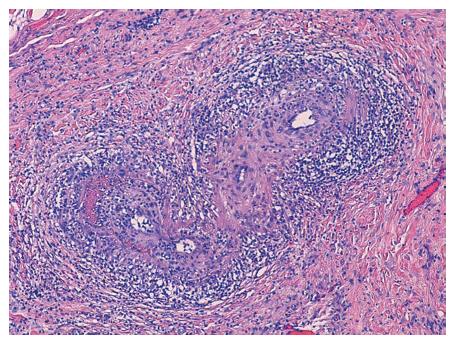

In the microscopic study, the liver specimen was compatible with nongranulomatous acute necrotizing vasculitis (Figure 2). The gallbladder sample (Figures 3 and 4) showed acute vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis in muscular arteries of parietal medium caliber. All these findings are compatible with PAN type vasculitis.

In the year of follow-up after the surgery, the patient has been treated with prednisone and cyclophosphamide with good results. Outpatient blood tests were negative for HBsAg and the autoimmunity study revealed positive antinuclear antibodies. After two months cyclophosphamide was discontinued because of pancytopenia, with the patient reaching a full recovery after drug suspension. Currently, one year after diagnosis, treatment consists of 10 mg of prednisone once a day, the patient is asymptomatic.

The diagnosis of PAN is presented as a challenge for the clinical practice. This is because it has mainly nonspecific symptoms, which may involve more than one organ and the absence of specific serological tests for this disease. PAN usually appears as a chronic disease with periods of remission and deterioration[5].

Hepatic involvement may be of a PAN clinical profile. Different clinical entities have been described in the literature ranging from chronic liver failure and cirrhosis to acute hepatitis, hepatic regeneration nodules and vascular and bile-duct complications. In most cases the pathogenesis involves immune complex depositions leading to obstruction in hepatic blood flow and obliteration of small vasculature resulting in aneurysm formation (13%-60%)[6-8]. These may cause complications of difficult diagnosis. Most patients are asymptomatic at the moment of diagnosis and only 10%-15% of patients with hepatic artery aneurysms have presenting symptoms, such as abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding or cholestasis[9].

Spontaneous intrahepatic hemorrhage caused by the rupture of a hepatic artery aneurysm is a rare complication of PAN, however it has a high mortality[10,11]. There are about fifteen reported cases in which the diagnosis of PAN was learned due to hemodynamic instability secondary to spontaneous hepatic rupture that required an urgent laparotomy, as in the case presented.

There are different options when deciding how to manage these patients. Some of the reported cases resolved the bleeding using vascular radiology techniques with selective artery embolization[12,13]. In other patients with hemodynamic stability expectant attitude was decided, administering blood transfusion after corticosteroid and immunosuppressive treatment[12,14-16]. In those cases in which surgical management was decided, most did not do any type of liver resection, opting for hepatic parenchyma hemostasis and packing[4,5] with high mortality rate.

In one case reported[17] a right hepatectomy surgery was performed on a 20-year-old with severe bleeding. This patient died after 12 wk because of several complications after surgery.

This article presents the first case in which an urgent major hepatectomy for treatment of a liver rupture secondary to a previously unknown PAN is performed. In this case the patient is still alive after approximately one year has passed without any kind of complication.

Early and proper diagnosis is decisive in this disease when it is not presented acutely as in the case presented. For this reason, a whole and exhaustive history is required. To confirm the diagnosis of PAN a pathological study is crucial. The biopsy can be obtained from muscle tissue. In cases where the biopsy can not be performed or it is assumed that it would be negative, arteriography is mandatory to confirm the presence of aneurysms[18]. After that, treatment with steroids and immunosuppressive drugs has been found to eliminate all clinical manifestations of the disease. Decrease of the aneurysm size and its risk of rupture has been described with this treatment[12].

The paper was supported by Reina Sofía University Hospital, 14004 Córdoba, Spain (Andalusia Public Health Service).

The patient reported feeling general malaise with unmeasured fever and she feels pain predominantly in right quadrants on the abdomen.

The most frequent at the beginning of disease symptoms are fever, weight loss, muscles pain, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal disorders and skin lesions.

For diagnosis, the criteria established by the American College of Rheumatology are often used, a high clinical suspicion, a biopsy showing vasculitis or arteriography showing aneurysms.

The increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein is practically constant during the active phase of the disease. Other common findings are leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and normochromic anemia.

Is useful to perform an arteriography or reconstructions high-quality computed tomography (CT)-scan imaging that showing the presence of aneurysms or occlusions of visceral arteries not display due to arteriosclerosis?

Histological alterations show granulocytes or granulocyte and mononuclear leukocytes into the arterial wall of medium diameter.

The treatment has undergone major changes in recent years although cyclophosphamide remains the cornerstone despite its side effects, there are promising new therapies such as biologic therapies.

There are several cases in the literature related to liver rupture due to polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) them out various treatment are carried with different results. There is so far an established treatment for this type of clinical presentation. The decision is based on the clinical condition of the patient and therapeutics means available in the hospital.

The patient had low suspicion of vasculitis, but had a history of hypertension, the presence of aneurysms in the CT-scan and a PAN conclusive biopsy. The hepatitis B surface antigen was negative and antinuclear antibodies were positive. It shows the difficult diagnosis of this disease and the need for a broad differential diagnosis.

In this case report, the authors show an uncommon PAN debuts with a spontaneous liver rupture as first symptom that requires urgent liver major resection in a patient without previous clinical manifestations.

This case report describes spontaneous liver rupture due to polyarteritis nodosa which was treated by surgical intervention. The paper is well written.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aseni P, Kubota K, Rothschild BM S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:603-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cowan RE, Mallinson CN, Thomas GE, Thomson AD. Polyarteritis nodosa of the liver: a report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1977;53:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mills PR, Sturrock RD. Clinical associations between arthritis and liver disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1982;41:295-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leung VK, Lam CY, Chan CC, Ng WL, Loke TK, Luk IS, Chau TN, Wu AH, Fong WN, Lam SH. Spontaneous intra-hepatic haemorrhage in a patient with fever of unknown origin. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:319-322. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Travers RL, Allison DJ, Brettle RP, Hughes GR. Polyarteritis nodosa: a clinical and angiographic analysis of 17 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1979;8:184-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sellar RJ, Mackay IG, Buist TA. The incidence of microaneurysms in polyarteritis nodosa. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1986;9:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ewald EA, Griffin D, McCune WJ. Correlation of angiographic abnormalities with disease manifestations and disease severity in polyarteritis nodosa. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:952-956. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kanai R, Nakamura M, Tomisato K, Fukuhara T, Kondo A, Nakamura S, Matsukawa S, Yabutani A, Kobashikawa K, Nakayoshi T. Cholangitis as an initial manifestation of polyarteritis nodosa. Intern Med. 2014;53:2307-2312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schröder W, Brandstetter K, Vogelsang H, Nathrath W, Siewert JR. Massive intrahepatic hemorrhage as first manifestation of polyarteritis nodosa. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:148-152. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Choy CW, Smith PA, Frazer C, Jeffrey GP. Ruptured hepatic artery aneurysm in polyarteritis nodosa: a case report and literature review. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67:904-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Battula N, Tsapralis D, Morgan M, Mirza D. Spontaneous liver haemorrhage and haemobilia as initial presentation of undiagnosed polyarteritis nodosa. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94:e163-e165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kühn JP, Hegenscheid K, Puls R. [Ruptured visceral artery aneurysm as the initial symptomatic manifestation of panarteritis nodosa]. Rofo. 2008;180:922-924. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Senaati S, Cekirge S, Akhan O, Balkanci F. Spontaneous perirenal and hepatic hemorrhage in periarteritis nodosa. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1993;44:49-51. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Alleman MJ, Janssens AR, Spoelstra P, Kroon HM. Spontaneous intrahepatic hemorrhages in polyarteritis nodosa. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:712-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bonomo L, De Pascale A, Di Giandomenico E, Gidaro G. Hepatic hematoma in polyarteritis nodosa. Rays. 1988;13:19-21. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Dzwonczyk J, Serlin O, Skerrett PV. Spontaneous rupture of the liver; report of a case secondary to polyarteritis nodosa. Ann Surg. 1959;150:327-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li AK, Rhodes JM, Valentine AR. Spontaneous liver rupture in polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Surg. 1979;66:251-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gumà M, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Olivé A, Perendreu J, Bechini J, Doménech E, Planas R. Occult liver involvement by polyarteritis nodosa. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:184-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |