Published online Jul 18, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i20.850

Peer-review started: March 28, 2016

First decision: April 19, 2016

Revised: May 5, 2016

Accepted: May 31, 2016

Article in press: June 2, 2016

Published online: July 18, 2016

Processing time: 107 Days and 15.7 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) combined with stomach and esophageal variceal embolization (SEVE) in cirrhotic patients with a large gastrorenal vessel shunt (GRVS).

METHODS: Eighty-one cirrhotic patients with gastric variceal bleeding (GVB) associated with a GRVS were enrolled in the study and accepted TIPS combined with SEVE (TIPS + SEVE), by which portosystemic pressure gradient (PPG), biochemical, TIPS-related complications, shunt dysfunction, rebleeding, and death were evaluated.

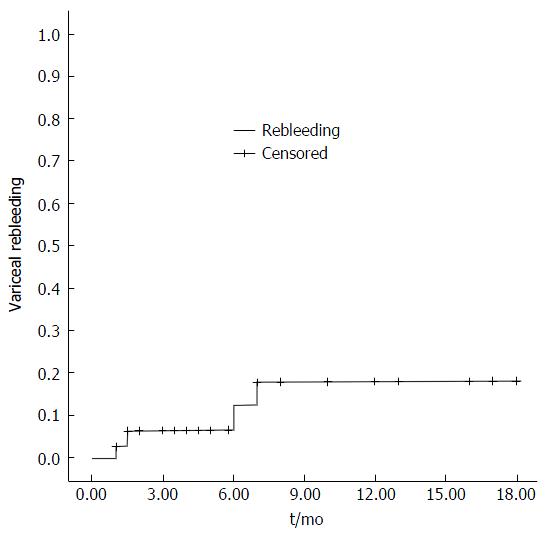

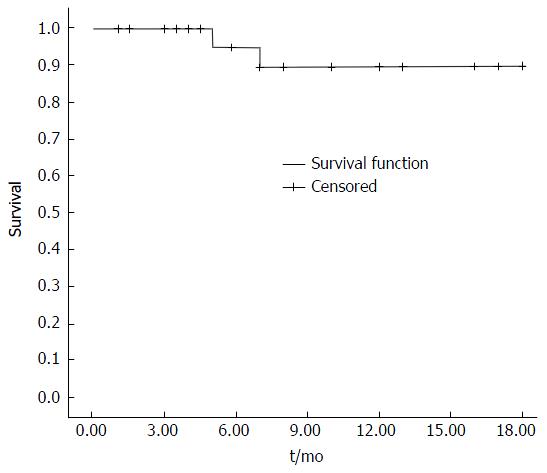

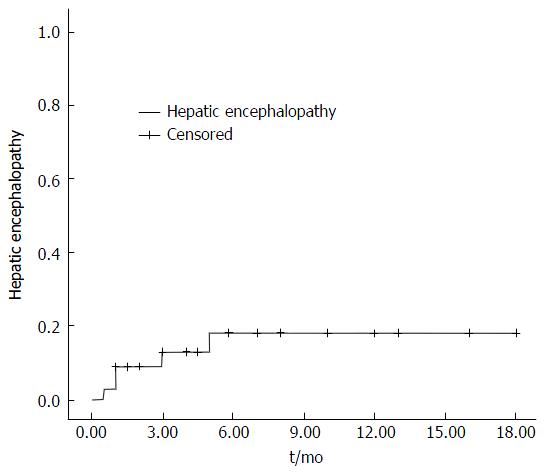

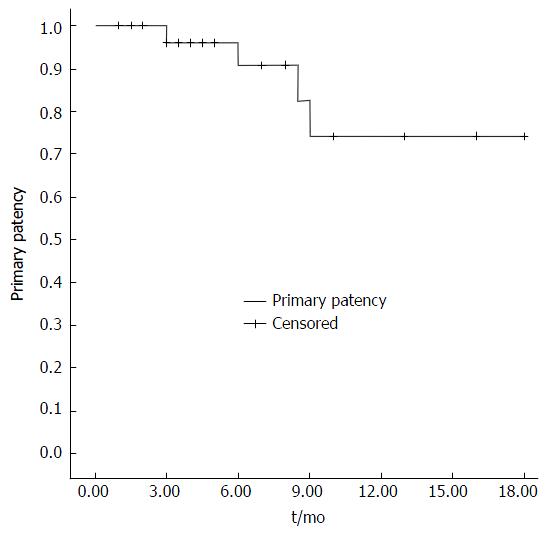

RESULTS: The PPGs before TIPS were greater than 12 mmHg in 81 patients. TIPS + SEVE treatment caused a significant decrease in PPG (from 37.97 ± 6.36 mmHg to 28.15 ± 6.52 mmHg, t = 19.22, P < 0.001). The percentage of reduction in PPG was greater than 20% from baseline. There were no significant differences in albumin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, prothrombin time, or Child-Pugh score before and after operation. In all patients, rebleeding rates were 3%, 6%, 12%, 18%, and 18% at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 mo, respectively. Five patients (6.2%) were diagnosed as having hepatic encephalopathy. The rates of shunt dysfunction were 0%, 4%, 9%, 26%, and 26%, at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 mo, respectively. The cumulative survival rates in 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 mo were 100%, 100%, 95%, 90%, and 90%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Our preliminary results indicated that the efficacy and safety of TIPS + SEVE were satisfactory in cirrhotic patients with GVB associated with a GRVS (GVB + GRVS).

Core tip: The optimal treatment of gastric variceal bleeding (GVB) + gastrorenal vessel shunt (GRVS) remains uncertain. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) alone cannot be widely used in the treatment of GVB + GRVS. Some studies have evaluated the short-term outcomes of cirrhosis treated with TIPS combined with variceal embolization. In this study, we found that the efficacy and safety of TIPS + stomach and esophageal variceal embolization were satisfactory for patients with GVB + GRVS.

- Citation: Jiang Q, Wang MQ, Zhang GB, Wu Q, Xu JM, Kong DR. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt combined with esophagogastric variceal embolization in the treatment of a large gastrorenal shunt. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(20): 850-857

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i20/850.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i20.850

Although the rate of gastric variceal bleeding (GVB) is significantly lower than that of esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB)[1,2], it is usually more severe, requires more transfusions, and is associated with higher mortality than EVB[1-3]. Currently, the optimal treatment of GVB remains a difficult issue for clinicians. In terms of recommendatory therapy for gastric varices, there are various primary options, including surgery, endoscopic variceal obturation with tissue adhesive, Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement, and balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration[4,5]. First-line therapies for gastric varices are endoscopically administered tissue adhesives and TIPS placement.

GVB is often associated with a gastrorenal vessel shunt (GRVS)[6]. The safety of endoscopically-administered tissue adhesives in patients with GVB + GRVS is controversial, due to potential cerebral or pulmonary embolism secondary to migration of cyanoacrylate into the systemic circulation through GRVS[7]. TIPS placement has been widely accepted as an effective and safe treatment for GVB in cirrhotic patients[4,8]. However, because the portosystemic pressure gradient (PPG) in patient with GVB + GRVS is lower than that in patient with EV, TIPS placement alone is seldom is used in the treatment of GVB + GRVS[9-13].

Recent years, some studies have shown that TIPS combined with variceal embolization prevented recurrent variceal bleeding and improved liver function[14,15]. However, there are no similar studies to evaluate the effectiveness of a combination of these two methods for patients with GVB + GRVS. The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TIPS + SEVE for patients with GVB + GRVS.

Between October 2013 and December 2015, a total of 107 patients in whom TIPS + SEVE had been successfully performed in our hospital were recruited for this study. Inclusion criteria were as follow: (1) age > 18 years; (2) history of cirrhosis and GVB (based on findings of histological or typical cross-sectional imaging, such as ultrasound, endoscopy, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging); and (3) patients was diagnosed as having GRVS by computed tomography angiography (CTA). Exclusion criteria were: (1) hepatocellular carcinoma or other malignancies; (2) chronic renal failure; (3) portal vein thrombosis; (4) infection; and (5) coagulation disorder. Of the 107 patients, 26 with EVB or GVB without GRVS were excluded from this study. Thus, the final population for study consisted of 81 patients. The main clinical and biochemical characteristics of these 81 patients are presented in Table 1. All patients provided their informed written consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University.

| No. of patients | 81 (%) |

| Men | 63 (77.8) |

| Female | 9 (22.2) |

| Age (yr) | |

| Mean ± SD | 50.9 ± 10.9 |

| Range | 25-76 |

| Cause of liver disease | n (%) |

| Viral | 61 (75.4) |

| Alcoholic | 7 (8.7) |

| Viral and alcoholic | 1 (1.2) |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 4 (4.9) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 (1.2) |

| Cryptogenic | 7 (8.6) |

| Child-Pugh class | n (%) |

| A | 15 (18.5) |

| B | 47 (58.0) |

| C | 19 (23.5) |

| Endoscopic findings | |

| IGV1 | 25 (30.9) |

| GOV1 | 10 (12.3) |

| GOV2 | 46 (56.8) |

| Pre-PPG (mmHg) | |

| Mean ± SD | 38.0 ± 6.4 |

| Range | 26.0-48.0 |

| Follow-up (mo) | |

| Mean ± SD | 7.87 ± 5.57 |

| Range | 1-18 |

Procedures were performed with general anesthesia in the angiography suite. The procedure of TIPS + SEVE has been described previously[14-16]. Briefly, before catheterization of the hepatic vein was performed through the right internal jugular vein, inferior vena cava pressure was measured when the tip of the catheter floated in the inferior vena cava at the junction with the hepatic vein. A needle and guide-wire were advanced through the liver parenchyma into a branch of the portal vein with fluoroscopic guidance, which was then followed by direct portography and measurement of portal vein pressure. A catheter was passed into the gastroesophageal collateral vessels and embolization of the collateral vessels was initiated, which formed coils of varying diameters and resulted in the disappearance of varices at post-embolization angiography. The catheter was then exited via the liver parenchyma. After the parenchymal tract between the hepatic vein and portal vein was dilated with an angioplasty balloon catheter, the patency of the TIPS was facilitated by deployment of a covered stent (8 mm in diameter, BARD E LUMINEXX Vascular Stent, France). The PPG was determined via the difference between the portal vein pressure and inferior vena cava pressure. The mid-chest was used as the external zero reference. Pressure tracings must remain stable for at least 30 s to be considered satisfactory. The mean value of two PPG measurements was used for analysis.

All patients received intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis 1 d before the procedure. Intravenous heparin was given as an anti-coagulate during the procedure and for 1 wk post-procedure, which then changed to oral aspirin and warfarin for 1 year. Oral lactulose was used to prevent hepatic encephalopathy (HE).

All patients were asked to enroll in the follow-up protocol. PPG, biochemical examination, TIPS-related complications, post-HE, primary patency, rebleeding, and death were recorded respectively. Patients were examined during follow-up with Doppler ultrasound, endoscopy, and CTA at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo after TIPS placement and then every 6 mo thereafter. Patients suffering from HE, rebleeding, or any other severe complications were invited to our TIPS unit at any time. Liver functions were assessed by testing albumin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), bilirubin, prothrombin time (PT) levels, and Child-Pugh score at 1 wk before and 1 mo after TIPS. TIPS patency could be assessed by Doppler ultrasonography. Endoscopy confirmed sources of bleeding and variceal disappearance. CTA was used to define the GRVS. Patients were followed until death or liver transplantation, while first rebleeding, first HE, and first shunt insufficiency were followed-up on to a maximum of 2 years after the procedure (closure date: December 31, 2015).

The following definitions were used: (1) rebleeding: Any subsequent hematemesis or melena confirmed endoscopically; (2) HE: Diagnosis of HE was made according to the final report of the 1998 Working Party at the 11th World Congress of Gastroenterology in Vienna[17], and patients with clinical evidence of HE were classified according to the West Haven criteria grades: HE ≥ grade I; (3) shunt dysfunction[18]: Doppler criteria for shunt insufficiency was that maximal flow velocity was less than 50 cm/s or that there was an absence of flow within the shunt. Suspected shunt dysfunction was confirmed by portography that showed shunt stenosis > 50%; (4) primary patency: The absence of shunt insufficiency without intervention during TIPS surveillance; and (5) endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices were recorded as proposed by the Japanese Society for portal hypertension[19].

The data were expressed as means ± SD. Quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t test. The rates of primary patency, HE, survival, and variceal rebleeding were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier analyses. A statistically significant difference was assessed for any of the analyses with results of P < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the SPSS 10.0 software package.

Table 2 summarizes the basic clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients. As shown, the PPG before TIPS placement was greater than 12 mmHg in all patients. The mean PPG dropped from 37.97 ± 6.36 mmHg to 28.15 ± 6.52 mmHg after TIPS (t = 19.22, P < 0.001), with reductions in PPG greater than 20% from baseline. There were no significant differences in albumin, ALT, AST, bilirubin, PT, or Child-Pugh score 1 wk before or 1 mo after operation.

| Before TIPS | After TIPS | P | |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 32.24 ± 5.88 | 33.90 ± 7.26 | 0.199 |

| ALT (u/L) | 30.00 ± 17.51 | 30.85 ± 20.60 | 0.806 |

| AST (u/L) | 38.00 ± 25.95 | 41.88 ± 24.03 | 0.318 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.41 ± 0.76 | 1.45 ± 0.65 | 0.561 |

| PT (%) | 52 ± 14 | 51 ± 15 | 0.903 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.4 | 0.58 |

| Child-Pugh score | 6.91 ± 1.44 | 6.79 ± 1.34 | 0.563 |

| PPG (mmHg) | 38.0 ± 6.4 | 28.2 ± 6.5 | < 0.001 |

Rebleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract occurred in ten patients (12.3%) after TIPS placement. One patient had 4 U of blood transfused within 24 h after the TIPS procedure, with no symptoms of rebleeding observed thereafter. The cumulative rates of rebleeding (Kaplan-Meier estimation) after 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 mo were 3%, 6%, 12%, 18%, and 18%, respectively. The actual probability of rebleeding is presented in Figure 1. One patient underwent tissue adhesive administration 6 mo after TIPS implantation and is, at the time of writing, alive and free of rebleeding. One patient was found to have portal hypertensive gastropathy, which resulted in rebleeding. The other rebleeding patients were found to have shunt stenosis or obstruction.

Five patients died within the follow-up period because of procedure-related complications. In one patient, a shunt obstruction was observed 6 mo after TIPS placement; the patient refused intervention treatment and died seven months after TIPS due to recurrent bleeding. The other four patients died 5 to 12 mo after TIPS placement. The cumulative rates of survival (Kaplan-Meier estimation) after 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 mo were 100%, 100%, 95%, 90%, and 90%, respectively. Survival curves are shown in Figure 2.

Five patients experienced HE sometimes before the operation and were also diagnosed as having HE after TIPS placement. A protein-restricted diet and/or lactulose treatment were given to prevent the recurrence of HE. The cumulative rates of HE (Kaplan-Meier estimation) after 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 mo were 9%, 13%, 18%, 18%, and 18%, respectively (Figure 3).

The cumulative rates of primary shunt patency (Kaplan-Meier estimation) after 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 mo were 100%, 96%, 91%, 74%, and 74%, respectively (Figure 4). During the follow-up period, 10 (12.3%) patients were diagnosed as having shunt stenosis or obstruction, of which 8 patients successfully underwent shunt recanalization with balloon angioplasty. Although one patient with shunt obstruction died 7 mo after TIPS (as previously mentioned), at the time of writing, the remaining patients are alive and well, albeit with one patient who had to receive anticoagulant therapy.

During the follow-up period, the rare complication of hepatic myelopathy (HM) occurred in two patients 6 to 8 mo after the TIPS procedure, which exerted a significant impact on their mobility and quality of life. Due to economic factors, the patients received conservative medical treatment and are, at the time of writing, alive.

The rate of GVB is significantly lower than that of EVB[1,2], but is usually more severe, requires more transfusions, and is associated with higher mortality than EVB[1-3]. Currently, the optimal treatment of GVB remains a difficult issue for clinicians.

Variceal embolotherapy has been recognized as an efficient method for preventing bleeding caused by portal hypertension[19,20], while TIPS is used worldwide for the prevention of variceal bleeding[4,5,8]. Previous studies have advocated TIPS combined with variceal embolization in the prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding and improvement of liver function[14,15]. However, there are no similar studies evaluating the combination of these two methods in patients with GVB + GRVS.

In the current study, we found that the PPG before TIPS placement was greater than 12 mmHg in patients with GVB + GRVS. All included patients had previously experienced at least one instance of bleeding. Ou et al[21] found that 35% (14/40) of patients with GVB had a PPG ≤ 12 mmHg at the time of TIPS[22]. The differing results may be related to the number of cases and the size of spontaneous GRVS in our study, despite previous studies illustrating that PPG appears to correlate inversely with the presence and size of spontaneous GRVS[6,21]; to date, there have been no attempts to measure the size of GRVS and the definition of GRVS size remains as yet undetermined.

It has been reported that patients with strong GVB have a lower PPG than those with EV, which may be a result of GRVS development[6,23]. Several studies have found that decompressive methods such as TIPS do not seem to confer much of a benefit for GVB + GRVS[9-13]. Our results suggest that the rebleeding rate after TIPS was 12% after 1 year, which was similar to the typically reported result of between 10% to 40%[24,25], while the reduction in PPG was greater than 20% from the baseline. Moreover, we noticed that TIPS + SEVE may reduce the risk of rebleeding. It should be noted that previous studies of TIPS differed from our own in that they used bare stents with TIPS alone placement or did not limit the stent diameter. In our study, all patients underwent decompressive operation and embolotherapy via coil, as well as the embolization of extensive collateral circulation (such as that of the short or posterior gastric vein), which may contribute to the occlusion of GRVS. All covered stents were dilated to 8 mm, which may be regarded as limited shunts that accord with natural hemodynamic features.

Survival is usually regarded as the strongest evidence for evaluating the effectiveness of a therapy. In previous studies, total survival 1-year post-TIPS ranged from 58% to 80% and depended mainly on the severity of the underlying liver disease[25,26]. The survival rate was 94% at 1 year in our study; such a high rate may be related to the patients’ liver function (76.5% patients with Child-Pugh class A or B). Although our results support patients with Child-Pugh class C as well, TIPS placement should be used with extreme caution. Taken together, improving liver function before TIPS may increase the survival rates.

TIPS has been extensively used within the last 20 years. Previous studies showed that TIPS increases the incidence of HE without improving survival[27-29], which may be the reason why it is currently only recommended as a rescue therapy. HE has been reported to occur in 16%-31% of patients who receive a TIPS in the presence of GVB + GRS[30]. Our results indicated that 15% of our patients were diagnosed as having HE after TIPS placement, which is very similar to the reports of other studies, and that only one patient required admission. Importantly, our results were attributed to three effective improvements. First, oral lactulose was used to prevent HE after operation. Second, the left portal vein could be successfully punctured in 58% patients. As we know, the left portal vein receives blood from the splenic vein and inferior mesenteric vein, which have fewer digestive products but more electrolytes. Most recent studies have illustrated that introducing TIPS to the left portal vein instead of the right portal vein could decrease the risk of HE[31-33]. Third, 8 mm stents were used in patients. It has been previously reported in the literature that the incidence of portosystemic HE increased with increasing diameter of the stent[31].

It has been shown that occlusion and stenosis are the main disadvantages of TIPS. Studies have demonstrated that stent insufficiency occurs in 14% to 82% of patients by 1 year post-TIPS[25,33]. Our findings suggest that 12% of patients in our study were diagnosed as having stenosis or obstruction one year after TIPS; our results therefore showed higher patency rates when compared to historical data. It was reported that the routine administration of anticoagulants and the use of covered stents play important roles in the improved patency rate[34-36]. Thus, the higher patency rate of our patients was partially attributed to the use of covered stents and anticoagulant therapy. Other possible reasons for our results are that patients were regularly followed-up on and that TIPS was placed in the left portal vein.

During the follow-up period, two patients were diagnosed with HM, in which the spontaneous shunt found by CTA was not completely closed. Embolization only with coils may be an insufficient embolization factor that was thought to be secondary to the increased systemic circulation of shunting portal venous toxins from the hypoperfusion and ischemia of the hepatocytes. Studies showed that a liver transplant could fully reverse the effects of HM in patients with early stage disease[37,38], however, due to economic factors, patients only received conservative medical treatment. Despite previous studies advocating TIPS combined with variceal embolization to improve liver function[15,39], there were no significant differences in liver functions before and after TIPS placement in our study.

In spite of these results, we may conclude that PPG before TIPS placement may be greater than 12 mmHg in patients with GVB + GRVS, and that the efficacy and safety of TIPS + SEVE were satisfactory in these patients.

The authors thank all patients involved in this study. We would also like to thank Professor Keyang Chen, from the Temple University School of Medicine, for language assistance.

The optimal treatment for gastric variceal bleeding (GVB) + gastrorenal vessel shunt (GRVS) is still controversial. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) alone cannot be widely used in the treatment for GVB + GRVS. Previous studies have advocated TIPS combined with variceal embolization in order to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding and improve liver function. However, the efficacy and safety of TIPS + stomach and esophageal variceal embolization (SEVE) in patients with GVB + GRVS was unclear.

In recent years, more and more patients have undergone TIPS procedure to prevent variceal bleeding. For the use of the TIPS procedure, the research hot spot is how to increase the patient survival rate and reduce complications by bettering the patient selection and improving techniques. Interestingly, TIPS + SEVE may decrease portal pressure and embolize extensive collateral circulation, thereby potentially reducing the risk of rebleeding.

Most GVB is associated with a GRVS. The efficacy of tissue adhesives in patients with GVB + GRVS is controversial, due to the potential for systemic embolism secondary to migration of cyanoacrylate into the systemic circulation through a GRVS. TIPS alone cannot be widely used in the treatment of GVB + GRVS. In the study, all patients underwent TIPS + SEVE with via coil, with extensive collateral circulation, such as short or posterior gastric vein, potentially contributing to the occlusion of GRVS. In this study, the authors found that the efficacy and safety of TIPS + SEVE were satisfactory in patients with GVB + GRVS.

The results suggest that the efficacy and safety of TIPS + SEVE were satisfactory in patients with GVB + GRVS. Additional studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm the results.

The authors have provided a well-designed study that shows the satisfactory efficacy and safety of combination TIPS + SEVE in cirrhotic patients with gastric variceal bleeding associated with a gastrorenal vessel shunt.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

P- Reviewer: Garbuzenko DV, Nakamura S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthy NS, Makwana UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: a long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 846] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (42)] |

| 2. | Kim T, Shijo H, Kokawa H, Tokumitsu H, Kubara K, Ota K, Akiyoshi N, Iida T, Yokoyama M, Okumura M. Risk factors for hemorrhage from gastric fundal varices. Hepatology. 1997;25:307-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thakeb F, Salem SA, Abdallah M, el Batanouny M. Endoscopic diagnosis of gastric varices. Endoscopy. 1994;26:287-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The Role of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) in the Management of Portal Hypertension: update 2009. Hepatology. 2010;51:306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1066] [Cited by in RCA: 1027] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Watanabe K, Kimura K, Matsutani S, Ohto M, Okuda K. Portal hemodynamics in patients with gastric varices. A study in 230 patients with esophageal and/or gastric varices using portal vein catheterization. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:434-440. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Irisawa A, Obara K, Sato Y, Saito A, Orikasa H, Ohira H, Sakamoto H, Sasajima T, Rai T, Odajima H. Adherence of cyanoacrylate which leaked from gastric varices to the left renal vein during endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: a histopathologic study. Endoscopy. 2000;32:804-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, Laleman W, Appenrodt B, Luca A, Abraldes JG, Nevens F, Vinel JP, Mössner J. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Caldwell S. Gastric varices: is there a role for endoscopic cyanoacrylates, or are we entering the BRTO era? Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1784-1790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matsumoto A, Matsushita M, Sugano Y, Takimoto K, Yasuda M, Inokuchi H. Limitations of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:380-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ryan BM, Stockbrugger RW, Ryan JM. TIPS for gastric varices. Gut. 2003;52:772; author reply 772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, Purdum PP, Shiffman ML, DeMeo J, Cole PE, Tisnado J. The natural history of portal hypertension after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:889-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Choi YH, Yoon CJ, Park JH, Chung JW, Kwon JW, Choi GM. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric variceal bleeding: its feasibility compared with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Korean J Radiol. 2003;4:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tesdal IK, Filser T, Weiss C, Holm E, Dueber C, Jaschke W. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: adjunctive embolotherapy of gastroesophageal collateral vessels in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. Radiology. 2005;236:360-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen S, Li X, Wei B, Tong H, Zhang MG, Huang ZY, Cao JW, Tang CW. Recurrent variceal bleeding and shunt patency: prospective randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt alone or combined with coronary vein embolization. Radiology. 2013;268:900-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rössle M, Haag K, Ochs A, Sellinger M, Nöldge G, Perarnau JM, Berger E, Blum U, Gabelmann A, Hauenstein K. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1594] [Cited by in RCA: 1410] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Han G, Qi X, He C, Yin Z, Wang J, Xia J, Yang Z, Bai M, Meng X, Niu J. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal vein thrombosis with symptomatic portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2011;54:78-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tajiri T, Yoshida H, Obara K, Onji M, Kage M, Kitano S, Kokudo N, Kokubu S, Sakaida I, Sata M. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (2nd edition). Dig Endosc. 2010;22:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kwok AC, Wang F, Maher R, Harrington T, Gananadha S, Hugh TJ, Samra JS. The role of minimally invasive percutaneous embolisation technique in the management of bleeding stomal varices. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1327-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ou HY, Huang TL, Chen TY, Tsang LL, Concejero AM, Chen CL, Cheng YF. Emergency splenic arterial embolization for massive variceal bleeding in liver recipient with left-sided portal hypertension. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1136-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tripathi D, Therapondos G, Jackson E, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. The role of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) in the management of bleeding gastric varices: clinical and haemodynamic correlations. Gut. 2002;51:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ohnishi K, Nakayama T, Koen H, Saito M, Saito M, Chin N, Terabayashi H, Iida S, Nomura F, Okuda K. Interrelationship between type of spontaneous portal systemic shunt and portal vein pressure in patients with liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:561-564. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Chao Y, Lin HC, Lee FY, Wang SS, Tsai YT, Hsia HC, Lin WJ, Lee SD, Lo KJ. Hepatic hemodynamic features in patients with esophageal or gastric varices. J Hepatol. 1993;19:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Garcia-Pagán JC, Barrufet M, Cardenas A, Escorsell A. Management of gastric varices. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:919-928.e1; quiz e51-e52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ryan BM, Stockbrugger RW, Ryan JM. A pathophysiologic, gastroenterologic, and radiologic approach to the management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1175-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Berry K, Lerrigo R, Liou IW, Ioannou GN. Association between Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt and Survival in Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;30:612-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Khan S, Tudur Smith C, Williamson P, Sutton R. Portosystemic shunts versus endoscopic therapy for variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD000553. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Escorsell A, Bañares R, García-Pagán JC, Gilabert R, Moitinho E, Piqueras B, Bru C, Echenagusia A, Granados A, Bosch J. TIPS versus drug therapy in preventing variceal rebleeding in advanced cirrhosis: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2002;35:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sabri SS, Abi-Jaoudeh N, Swee W, Saad WE, Turba UC, Caldwell SH, Angle JF, Matsumoto AH. Short-term rebleeding rates for isolated gastric varices managed by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:355-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Xue H, Yuan J, Chao-Li Y, Palikhe M, Wang J, Shan-Lv L, Qiao W. Follow-up study of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the treatment of portal hypertension. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3350-3356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen L, Xiao T, Chen W, Long Q, Li R, Fang D, Wang R. Outcomes of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt through the left branch vs. the right branch of the portal vein in advanced cirrhosis: a randomized trial. Liver Int. 2009;29:1101-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bai M, He CY, Qi XS, Yin ZX, Wang JH, Guo WG, Niu J, Xia JL, Zhang ZL, Larson AC. Shunting branch of portal vein and stent position predict survival after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:774-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, Pomier-Layrargues G, Chabbert V, Cortez C, Perreault P, Péron JM, Abraldes JG, Bouchard L. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:469-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yang Z, Han G, Wu Q, Ye X, Jin Z, Yin Z, Qi X, Bai M, Wu K, Fan D. Patency and clinical outcomes of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents versus bare stents: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1718-1725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sauer P, Theilmann L, Herrmann S, Bruckner T, Roeren T, Richter G, Stremmel W, Stiehl A. Phenprocoumon for prevention of shunt occlusion after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 1996;24:1433-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Baccarani U, Zola E, Adani GL, Cavalletti M, Schiff S, Cagnin A, Poci C, Merkel C, Amodio P, Montagnese S. Reversal of hepatic myelopathy after liver transplantation: fifteen plus one. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1336-1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Weissenborn K, Tietge UJ, Bokemeyer M, Mohammadi B, Bode U, Manns MP, Caselitz M. Liver transplantation improves hepatic myelopathy: evidence by three cases. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:346-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |