Published online Jan 18, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i2.117

Peer-review started: October 7, 2015

First decision: November 6, 2015

Revised: December 19, 2015

Accepted: January 5, 2016

Article in press: January 7, 2016

Published online: January 18, 2016

Processing time: 100 Days and 6.5 Hours

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an emerging pathogen and an increasingly recognized cause of graft hepatitis, especially in the post-orthotopic liver transplantation immunocompromised population. The exact incidence and prevalence of HEV infection in this population remains unclear but is certainly greater than historical estimates. Identifying acute HEV infection in this population is imperative for choosing the right course of management as it is very difficult to distinguish histologically from acute rejection on liver biopsy. Current suggested approach to manage acute HEV involves modifying immunosuppression, especially discontinuing calcineurin inhibitors which are the preferred immunosuppressive agents post-orthotopic liver transplantation. The addition of ribavirin monotherapy has shown promising success rates in clearing HEV infection and is used commonly in reported cases.

Core tip: Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an emerging pathogen in developed countries and an important cause of graft hepatitis in the post-orthotopic liver transplantation population that is often misdiagnosed either due to low index of suspicion or due to poor diagnostic assays. We recommend mandatory HEV testing in such cases, and careful treatment with modification of immunosuppression, especially switching from calcineurin inhibitors to a different class. Ribavirin has shown to be increasingly successful in treating HEV infection and preventing graft failure from acute HEV infection, if diagnosed early.

- Citation: Aggarwal A, Perumpail RB, Tummala S, Ahmed A. Hepatitis E virus infection in the liver transplant recipients: Clinical presentation and management. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(2): 117-122

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i2/117.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i2.117

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is one of the major causes of acute viral hepatitis globally. HEV genotypes vary globally in terms of transmission and pathogenicity (Table 1). There have been large scale epidemics of HEV across the low and middle income countries of Asia and Africa as well as sporadic cases in the same geographical regions[1]. More recently, HEV has been identified as an emerging pathogen in developed countries as well, particularly among immunosuppressed solid organ transplant recipients.

| Characteristics | Genotype 1 | Genotype 2 | Genotype 3 | Genotype 4 |

| Geographic location | Africa and Asia | Mexico and West Africa | Developed countries | China, Taiwan, Japan |

| Transmission | Water-borne, fecal oral, person to person | Water-borne, fecal oral, person to person | Food-borne | Food-borne |

| Group at high risk for infection | Young adults | Young adults | Older adults (> 40 yr) and males. Immuno-compromised persons | Young adults |

| Zoonotic transmission | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Chronic infection | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Occurrence of outbreaks | Common | Smaller scale outbreaks | Uncommon | Uncommon |

The overall prevalence varies greatly among existing studies, which are primarily from Europe. In the United States, diagnoses of symptomatic autochronous HEV infection are very rare compared to the number of cases reported in several European countries. The annual incidence of de-novo HEV infection in the United States is reported to be approximately 0.7%[2]. However, it is interesting that serological evidence of HEV exposure is more common than expected in a low endemic area like the United States (around 21%)[3,4]. In general, HEV seroprevalence was found to be higher in liver transplant recipients, particularly those with liver cirrhosis (7.4% and 32.1%, respectively)[5]. Whether cirrhosis is a predisposing factor for HEV or whether HEV infection may play a role in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis, remains controversial.

HEV has been identified as a cause of graft hepatitis in liver transplant recipients. The true frequency and clinical importance of HEV infections after liver transplantation is still unclear[6]. A study conducted in France estimated pre-transplant anti-HEV IgG prevalence as 29% increasing regularly with age from 7% in children < 15 years old to 49% for adults > 60 years old[7]. On follow-up, the annual incidence of HEV infection post-transplantation was 2.1% in previously seronegative patients, and it was much higher than that those found in other areas of the world. In previously seropositive patients, the annual incidence of post-transplantation re-infections detected by HEV RNA was 3.3%, an incidence similar to that of de novo infection[8]. Another group in the Netherlands retrospectively estimated HEV prevalence in a cohort of 285 adult liver transplant recipients and found 274 (96.1%) to be negative for all HEV parameters (HEV RNA, IgM/IgG). The prevalence of acquired de novo HEV hepatitis in this cohort was 1%-2% after transplantation. Therefore, despite low prevalence, chronic hepatitis E needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of graft hepatitis[9,10].

HEV in most individuals is known as self-limiting, acute, icteric hepatitis which recovers without sequelae in most cases. Case fatality rates in the general population can vary from 0.1% to 3.0%[11]. However, pregnant women often have worse outcomes with more likelihood of progression to fulminant liver failure and a case fatality rate of 10%-20% or higher, especially in developing countries[12]. Although the usual outcome of HEV is favorable, in a minority of cases, fulminant liver failure often leads to liver transplantation have been well described, many in non-endemic areas and autochthonous without any evidence of foreign exposure. HEV testing thus should be performed during the initial evaluation of every acute liver failure regardless of epidemiological context[13,14].

In patients with chronic liver disease, acute viral hepatitis from HEV can worsen rapidly to a syndrome called acute on chronic liver failure leading to very high mortality (0%-67% with a median of 34%)[1]. In immunocompromised individuals, HEV can take up a more chronic course with prolonged viremia[15]. Those with solid organ transplant have been studied the most with overall chronic HEV infections reported in up to 50%-60% of organ transplant recipients[16]. The chronic HEV infection usually manifests as mild elevation in liver enzymes without clinical signs of overt hepatitis. However rapid fibrosis progression causing cirrhosis within 1-2 years of infection and graft failure is seen in some cases[9,16,17]. Prospective study by Kamar et al[18] evaluated evolution of liver fibrosis in chronic HEV infected 16 organ transplant patients by sequential liver biopsies. Three out of 16 patients progressed to cirrhosis and two out of these died from decompensated cirrhosis[18]. The same group looked at virological and immunological factors associated with viral persistence leading to chronic infection in solid organ transplant (SOT) patients. The patients that had progressive liver fibrosis were found to have less quasispecies diversification during the first year than patients without liver fibrosis progression. This along with a weak inflammatory response [low serum concentrations of interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist and soluble IL-2 receptor] and high serum concentrations of the chemokines involved in leukocyte recruitment to the liver in the acute phase were associated with persistent HEV infection[19]. HEV related extra-hepatic manifestations like neurological symptoms, kidney injuries and hematological disorders have also been reported[20]. Most of chronic HEV infection cases observed belonged to genotype 3, however there are recent reports of genotype 4 infections as well[21,22].

A high index of suspicion is needed in patients with graft hepatitis of unclear etiology since graft failure can result from missed chronic HEV infection. Cases where re-transplantation was done as a last resort have been described[23]. Similarly, in allo-hematopoetic stem cell transplant recipients, liver enzyme abnormalities are often attributed to hepatic graft vs host disease or drug induced liver injury and possibility of HEV infection is overlooked[24]. Presence of anti-HEV antibodies may not protect against re-infection, especially in low concentrations (< 7 World Health Organization units/mL)[8].

A study in France compared SOT recipients who developed chronic HEV infection with those who cleared infection. In general acute aminotransferase levels were higher in those who cleared their infection. Also levels of IgM, IgG anti-HEV antibodies and HEV RNA during acute infection phase were not predictive of whether or not the infection will become chronic. In acute phase itself, only 24% had abnormal bilirubin levels[25]. This further emphasizes that an acute HEV infection can be easily missed unless clinician had a high index of suspicion. Now there is increasingly common recognition of HEV and this emerging pathogen is coming within the spectrum of differential diagnosis of US physicians.

Currently available antibody assays have shown low and variable sensitivity[26,27]. In severely immunocompromised person, anti-HEV IgG detection could be false negative. Comparison of two commercially available assays (Adaltis and Wantai) showed a wide discrepancy in results. Anti-HEV IgG positivity among both assays was wide (10.9% vs 31.3%, P = 0.005). On immunoblot, specificity of both assays remained 80%-86%. For anti-HEV IgM testing, both assays were concordant for 97% of the serum samples[28].

Also there was a considerable variability in the accuracy of PCR tests assays used in various studies from Europe from where most of our data regarding HEV infection has been derived[29].

The testing for HEV hence should be done during initial evaluation of graft dysfunction irrespectively since histological appearance on liver biopsy may not clearly distinguish rejection and acute viral hepatitis.

Early diagnosis of HEV should lead to prompt treatment particularly adjusting the immunosuppressive drug regimen as some drugs have been shown to exert opposing effects on HEV replication[30].

Immunosuppressive therapy has been proposed to be a key factor for developing chronic hepatitis E in organ transplant recipients[31] and is often attributed to diminished antiviral immunity. However, the effect of various immunosuppressive agents on HEV replication is lesser known. Role of steroids is particularly important in the setting of liver transplantation as it is known that steroid boluses used to treat acute rejection in HCV patients can increase the severity of HCV recurrence and viral load. Wang et al[30] studied the different immunosuppressants in two HEV replication models. They demonstrated that steroid (prednisone and dexamethasone) did not affect viral replication. It was also demonstrated that calcineurin inhibitors (CsA and FK506) promoted HEV infection. In fact the use of FK506 was found to be the main predictive factor for chronic hepatitis E in organ recipients in another study by Kamar et al[16,18]. On the other hand mycophenolic acid/mycophenolate mofetil (MPA/MMF) suppressed viral infection in replica model. The clinical benefit was demonstrated in heart transplant recipients where MMF containing regimens were assumed to play a role in more frequent HEV clearance[17]. These were in vitro studies and will need further validation with randomized controlled clinical trials. Nevertheless the results provide valuable reference for the management of immunosuppression in these patients.

Pegylated-interferon alpha (Peg-IFNα) is a strong immune-stimulatory drug that is being already used for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C infections. However Peg-IFNα is suggested to induce allogenic immunity, leading to transplant rejection in patients after solid organ transplantation which possibly limits its use in the treatment of chronic hepatitis E.

Successful use of Peg-IFNα therapy for chronic HEV has been reported in a patient with hemodialysis dependent end stage renal disease after failed renal transplant after 3 mo of therapy and achievement of sustained viral response (SVR) at 6 mo[32]. The use of Peg-IFNα in post-orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) patients was successful in achieving SVR, albeit with variable and longer course of therapy[33,34]. A recent systemic review found total 8 patients treated with Peg-IFN. SVR was achieved in 6 out of 8 patients (75%) after cessation of therapy, but only 2 out of 8 patients (25%) achieved SVR at or greater than 6 mo. Also 2 patients experienced acute rejection of their transplant organ during treatment[35]. This suggests the use of other antiviral agents like ribavirin preferable option, especially in post-OLT chronic HEV.

Despite a clear benefit to manipulating immunosuppressive regimens, a substantial proportion of patients are still not able to clear the virus and rapidly progress toward chronic hepatitis[16]. Although no proven medication is available, the use of ribavirin monotherapy as an off label drug is gaining acceptance for treating hepatitis E. There is not enough data to recommend treatment with role of ribavirin (RBV) for adult liver transplant recipients, although this has been previously well studied in other SOT populations including lung[36], heart[17], kidney[37,38], and kidney-pancreas[39] transplantation. A large retrospective multicenter case series to assess the effects of RBV as monotherapy for SOT was done by Kamar et al[40]. It included 59 SOT patients (37 kidney, 10 liver, 5 heart, 5 kidney pancreas, and 2 lung) with prolonged HEV viremia. Fifty-four out of 59 had genotyping performed and were HEV genotype 3. Ninety-five percent had HEV clearance with RBV median therapy duration of 3 mo (1-18 mo). SVR measured as undetectable serum HEV RNA at 6 mo after therapy cessation was observed in 46 out of 59 (78%) patients[40]. Recently, there have been several case reports of RBV monotherapy for post orthotropic liver transplant, the earliest case reporting SVR-8 following 16 wk therapy[41]. Pischke et al[42] demonstrated successful HEV clearance with RBV monotherapy at 600 mg daily for 5 mo in 11 liver transplant patients.

There have been small number of patients who were non responders to antiviral therapy. One of the identified mutations is G1634R mutation in viral polymerase that was detected in HEV RNA of non-responders. Although there was no resistance to RBV in mutated HEV in vitro, bit this mutant form of a sub-genomic replicon of genotype 3 HEV replicated more efficiently in vitro than the non-mutant strains. Similar results were seen for infectious virus in competition assays[43]. Also, interestingly a higher lymphocyte count at the time of RBV initiation was associated with a greater likelihood of achieving SVR[40].

The exact mode of action of RBV against HEV is not known but successful clearance of both HEV genotype 1 and 3 indicate broad antiviral activity across genotypes[42]. However the standard dose and duration of RBV is yet to be determined. Successful outcomes with RBV monotherapy along with tailoring of immunosuppression regimen could provide an acceptable management approach to post OLT HEV. A beneficial effect of combining ribavirin with MPA was seen in vitro as well[30].

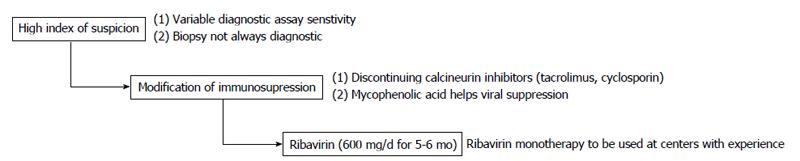

HEV is an emerging pathogen and an increasingly recognized cause of graft hepatitis especially in the post-OLT immunocompromised population. The exact incidence and prevalence of HEV infection in this population might be unclear but certainly more than historical estimates. Identifying acute HEV infection in this population is imperative for choosing the right course of management as it is very difficult to distinguish histologically from acute rejection on liver biopsy. The current suggested approach to manage acute HEV involves modifying immunosuppression, especially discontinuing calcineurin inhibitors which are the preferred immunosuppressive agents post-OLT. Along with immunosuppression modification, addition of RBV monotherapy has shown promising success rate in clearing HEV infection with current studies suggest using RBV 600 mg/d for a minimum of 5-6 mo successfully with a high SVR rate. We recommend maintaining high index of suspicion and mandatory confirmatory testing for HEV infection in post-OLT hepatitis with careful use of RBV in cases of established diagnosis (Figure 1).

P- Reviewer: Ajith TA, Arias J, Chiang TA, Sazci A, Wang K, Waisberg J, Zhang XC S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Kumar A, Saraswat VA. Hepatitis E and Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3:225-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Faramawi MF, Johnson E, Chen S, Pannala PR. The incidence of hepatitis E virus infection in the general population of the USA. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:1145-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kuniholm MH, Purcell RH, McQuillan GM, Engle RE, Wasley A, Nelson KE. Epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in the United States: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:48-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nelson KE, Kmush B, Labrique AB. The epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infections in developed countries and among immunocompromised patients. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:1133-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Riveiro-Barciela M, Buti M, Homs M, Campos-Varela I, Cantarell C, Crespo M, Castells L, Tabernero D, Quer J, Esteban R. Cirrhosis, liver transplantation and HIV infection are risk factors associated with hepatitis E virus infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Behrendt P, Steinmann E, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. The impact of hepatitis E in the liver transplant setting. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1418-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Buffaz C, Scholtes C, Dron AG, Chevallier-Queyron P, Ritter J, André P, Ramière C. Hepatitis E in liver transplant recipients in the Rhône-Alpes region in France. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:1037-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abravanel F, Lhomme S, Chapuy-Regaud S, Mansuy JM, Muscari F, Sallusto F, Rostaing L, Kamar N, Izopet J. Hepatitis E virus reinfections in solid-organ-transplant recipients can evolve into chronic infections. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1900-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pischke S, Suneetha PV, Baechlein C, Barg-Hock H, Heim A, Kamar N, Schlue J, Strassburg CP, Lehner F, Raupach R. Hepatitis E virus infection as a cause of graft hepatitis in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:74-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Haagsma EB, Niesters HG, van den Berg AP, Riezebos-Brilman A, Porte RJ, Vennema H, Reimerink JH, Koopmans MP. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus infection in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1225-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mushahwar IK. Hepatitis E virus: molecular virology, clinical features, diagnosis, transmission, epidemiology, and prevention. J Med Virol. 2008;80:646-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Navaneethan U, Al Mohajer M, Shata MT. Hepatitis E and pregnancy: understanding the pathogenesis. Liver Int. 2008;28:1190-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ohnishi S, Kang JH, Maekubo H, Takahashi K, Mishiro S. A case report: two patients with fulminant hepatitis E in Hokkaido, Japan. Hepatol Res. 2003;25:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aherfi S, Borentain P, Raissouni F, Le Goffic A, Guisset M, Renou C, Grimaud JC, Hardwigsen J, Garcia S, Botta-Fridlund D. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure related to autochthonous genotype 3 hepatitis E virus infection. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wedemeyer H, Pischke S, Manns MP. Pathogenesis and treatment of hepatitis e virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1388-1397.e1. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kamar N, Garrouste C, Haagsma EB, Garrigue V, Pischke S, Chauvet C, Dumortier J, Cannesson A, Cassuto-Viguier E, Thervet E. Factors associated with chronic hepatitis in patients with hepatitis E virus infection who have received solid organ transplants. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1481-1489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pischke S, Stiefel P, Franz B, Bremer B, Suneetha PV, Heim A, Ganzenmueller T, Schlue J, Horn-Wichmann R, Raupach R. Chronic hepatitis e in heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3128-3133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kamar N, Abravanel F, Selves J, Garrouste C, Esposito L, Lavayssière L, Cointault O, Ribes D, Cardeau I, Nogier MB. Influence of immunosuppressive therapy on the natural history of genotype 3 hepatitis-E virus infection after organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lhomme S, Abravanel F, Dubois M, Sandres-Saune K, Rostaing L, Kamar N, Izopet J. Hepatitis E virus quasispecies and the outcome of acute hepatitis E in solid-organ transplant patients. J Virol. 2012;86:10006-10014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kamar N, Rostaing L, Izopet J. Hepatitis E virus infection in immunosuppressed patients: natural history and therapy. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Geng Y, Zhang H, Huang W, J Harrison T, Geng K, Li Z, Wang Y. Persistent hepatitis e virus genotype 4 infection in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hepat Mon. 2014;14:e15618. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Perumpail RB, Ahmed A, Higgins JP, So SK, Cochran JL, Drobeniuc J, Mixson-Hayden TR, Teo CG. Fatal Accelerated Cirrhosis after Imported HEV Genotype 4 Infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1679-1681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu X, Shen T, Wang Z, Zhuang L, Zhang W, Yu J, Wu J, Zheng S. Hepatitis E virus infection results in acute graft failure after liver transplantation: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:245-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | van der Eijk AA, Pas SD, Cornelissen JJ, de Man RA. Hepatitis E virus infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Legrand-Abravanel F, Kamar N, Sandres-Saune K, Garrouste C, Dubois M, Mansuy JM, Muscari F, Sallusto F, Rostaing L, Izopet J. Characteristics of autochthonous hepatitis E virus infection in solid-organ transplant recipients in France. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:835-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bendall R, Ellis V, Ijaz S, Ali R, Dalton H. A comparison of two commercially available anti-HEV IgG kits and a re-evaluation of anti-HEV IgG seroprevalence data in developed countries. J Med Virol. 2010;82:799-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Reuter S, Oette M, Wilhelm FC, Beggel B, Kaiser R, Balduin M, Schweitzer F, Verheyen J, Adams O, Lengauer T. Prevalence and characteristics of hepatitis B and C virus infections in treatment-naïve HIV-infected patients. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2011;200:39-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rossi-Tamisier M, Moal V, Gerolami R, Colson P. Discrepancy between anti-hepatitis E virus immunoglobulin G prevalence assessed by two assays in kidney and liver transplant recipients. J Clin Virol. 2013;56:62-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Baylis SA, Hanschmann KM, Blümel J, Nübling CM. Standardization of hepatitis E virus (HEV) nucleic acid amplification technique-based assays: an initial study to evaluate a panel of HEV strains and investigate laboratory performance. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1234-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wang Y, Zhou X, Debing Y, Chen K, Van Der Laan LJ, Neyts J, Janssen HL, Metselaar HJ, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. Calcineurin inhibitors stimulate and mycophenolic acid inhibits replication of hepatitis E virus. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1775-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kamar N, Selves J, Mansuy JM, Ouezzani L, Péron JM, Guitard J, Cointault O, Esposito L, Abravanel F, Danjoux M. Hepatitis E virus and chronic hepatitis in organ-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:811-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1005] [Cited by in RCA: 998] [Article Influence: 58.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kamar N, Abravanel F, Garrouste C, Cardeau-Desangles I, Mansuy JM, Weclawiak H, Izopet J, Rostaing L. Three-month pegylated interferon-alpha-2a therapy for chronic hepatitis E virus infection in a haemodialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2792-2795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Haagsma EB, Riezebos-Brilman A, van den Berg AP, Porte RJ, Niesters HG. Treatment of chronic hepatitis E in liver transplant recipients with pegylated interferon alpha-2b. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:474-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kamar N, Rostaing L, Abravanel F, Garrouste C, Esposito L, Cardeau-Desangles I, Mansuy JM, Selves J, Peron JM, Otal P. Pegylated interferon-alpha for treating chronic hepatitis E virus infection after liver transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:e30-e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Peters van Ton AM, Gevers TJ, Drenth JP. Antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis E: a systematic review. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:965-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Riezebos-Brilman A, Puchhammer-Stöckl E, van der Weide HY, Haagsma EB, Jaksch P, Bejvl I, Niesters HG, Verschuuren EA. Chronic hepatitis E infection in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Moal V, Motte A, Kaba M, Gerolami R, Berland Y, Colson P. Hepatitis E virus serological testing in kidney transplant recipients with elevated liver enzymes in 2007-2011 in southeastern France. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76:116-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | de Niet A, Zaaijer HL, ten Berge I, Weegink CJ, Reesink HW, Beuers U. Chronic hepatitis E after solid organ transplantation. Neth J Med. 2012;70:261-266. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Mallet V, Nicand E, Sultanik P, Chakvetadze C, Tessé S, Thervet E, Mouthon L, Sogni P, Pol S. Brief communication: case reports of ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis E. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kamar N, Izopet J, Tripon S, Bismuth M, Hillaire S, Dumortier J, Radenne S, Coilly A, Garrigue V, D’Alteroche L. Ribavirin for chronic hepatitis E virus infection in transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1111-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Klein F, Neuhaus R, Hofmann J, Rudolph B, Neuhaus P, Bahra M. Successful Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis E After an Orthotopic Liver Transplant With Ribavirin Monotherapy. Exp Clin Transplant. 2015;13:283-286. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Pischke S, Hardtke S, Bode U, Birkner S, Chatzikyrkou C, Kauffmann W, Bara CL, Gottlieb J, Wenzel J, Manns MP. Ribavirin treatment of acute and chronic hepatitis E: a single-centre experience. Liver Int. 2013;33:722-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Debing Y, Gisa A, Dallmeier K, Pischke S, Bremer B, Manns M, Wedemeyer H, Suneetha PV, Neyts J. A mutation in the hepatitis E virus RNA polymerase promotes its replication and associates with ribavirin treatment failure in organ transplant recipients. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1008-1011.e7; quiz e15-16. [PubMed] |