Published online Jun 18, 2016. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i17.703

Peer-review started: February 19, 2016

First decision: April 5, 2016

Revised: April 24, 2016

Accepted: May 17, 2016

Article in press: May 27, 2016

Published online: June 18, 2016

Processing time: 117 Days and 23.9 Hours

Therapeutic management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is quite complex owing to the underlying cirrhosis and portal vein hypertension. Different scores or classification systems based on liver function and tumoral stages have been published in the recent years. If none of them is currently “universally” recognized, the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system has become the reference classification system in Western countries. Based on a robust treatment algorithm associated with stage stratification, it relies on a high level of evidence. However, BCLC stage B and C HCC include a broad spectrum of tumors but are only matched with a single therapeutic option. Some experts have thus suggested to extend the indications for surgery or for transarterial chemoembolization. In clinical practice, many patients are already treated beyond the scope of recommendations. Additional alternative prognostic scores that could be applied to any therapeutic modality have been recently proposed. They could represent complementary tools to the BCLC staging system and improve the stratification of HCC patients enrolled in clinical trials, as illustrated by the NIACE score. Prospective studies are needed to compare these scores and refine their role in the decision making process.

Core tip: Different scores or classification systems have been proposed to refine hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis and better guide medical treatment. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system has become the reference classification in Western countries. Its treatment algorithm is based on randomized studies, but only offers one recommendation for BCLC stages B and C, whereas they include a broad spectrum of tumors. In clinical practice, many patients are treated out of the scope of these recommendations. In this context, alternative scores or classifications, which have been opposed for a long time, could be complementary tools for the benefit of the treatment.

- Citation: Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Raoul JL, Le Treut P, Bollon E, Hardwigsen J, Castellani P, Perrier H, Bourlière M. Usefulness of staging systems and prognostic scores for hepatocellular carcinoma treatments. World J Hepatol 2016; 8(17): 703-715

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v8/i17/703.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i17.703

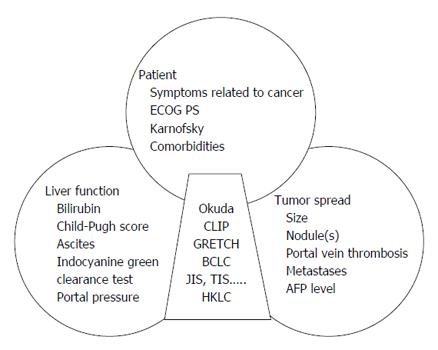

Most hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) develop upon chronic diseases of the liver, mainly B or C viral hepatitis. HCC is a frequent and serious cancer, often diagnosed at an inoperable stage[1]. It is singular as its prognosis not only relies on the tumor characteristics but also on the underlying liver disease, frequently at a cirrhotic stage. The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification of solid tumors failed to impose itself as the reference system for such a dual pathology, despite its recognized prognostic value even for non-operated tumors[2]. In order to refine the prognosis and provide better medical care, different scores or classifications originating from Asian or Western countries have been published recently. Most of them use regression models based on the prognostic variables of the studied populations. If they all share common parameters including liver function, tumor characteristics, age-related clinical consequences, comorbidities or cirrhosis (Figure 1), there is no universally recognized score or classification to date.

In the first part, we will focus on the main scores and classification systems published in the recent years, following a chronological order and revealing the differences between Western and Asian countries, the corresponding affected populations, treatment modalities and recommendations being distinct. The second part highlights the complementarity between the two systems in the decision making process (excluding graft), as successively exemplified by the sorafenib, the transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), the radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and the surgical resection treatments.

The OKUDA score, published in the eighties, was the first to combine tumor-associated parameters (more vs less than 50% of invaded parenchyma) and liver function (ascites, albumin, bilirubin) (Tables 1 and 2). It classifies patients into three stages [lowly (I), moderately (II) or highly advanced (III)] with different outcomes, depending on their number of positive variables (0 vs 1-2 vs 3-4, respectively). This score was initially validated on a population of 850 patients, either non-treated or treated according to the modalities applicable at that time (surgery, intra-arterial or systemic chemotherapy, arterial embolization)[3]. Although approximative and hardly differentiating the less advanced patients (e.g., the median survival of stage I patients was 11.5 mo independently of the treatment vs 25.6 mo when operated), this score has been widely used.

| Scores and classifications | Liver function | AFP | PS | Tumor spread |

| Okuda 1985 | Ascites, albumin, bilirubin | No | No | Hepatic spread 50% < vs > 50% |

| CLIP 1998 | Child-Pugh score | < 400 ng/mL vs≥ 400 ng/mL | No | Nodule(s), hepatic spread 50% ≤vs > 50% |

| Portal vein thrombosis | ||||

| GRETCH 1999 | Bilirubine, phosphatases alcalines | < 35 ng/mL vs≥ 35 ng/mL | Yes | Portal vein thrombosis |

| BCLC 1999 | Child-Pugh score | No | Yes | Nodule(s), size |

| Portal vein thrombosis | ||||

| c-JIS 2003 | Child-Pugh score | No | No | TNM LCSGJ |

| bm-JIS 2008 | Child-Pugh score | Yes (+ AFP-L3 + DCP) | No | TNM LCSGJ |

| TIS 2010 | Child-Pugh score | < 400 g/mL ≥ 400 ng/mL | No | Total tumor volume |

| HKLC 2014 | Child-Pugh score | No | Yes | Nodule(s), size |

| Portal vein thrombosis |

| Okuda score | CLIP score | ||||

| Parameters | (+) 1 point | (-) 0 point | 0 point | 1 point | 2 points |

| Tumor spread | > 50% | < 50% | |||

| Albumin, g/dL | < 3 | > 3 | |||

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | > 3 | < 3 | |||

| Ascites | Yes | No | |||

| Child-Pugh score | A | B | C | ||

| Tumor spread | Unipolar and hepatic spread ≤ 50% | Multinodular and hepatic spread ≤ 50% | Massive or hepatic spread > 50% | ||

| Portal vein thrombosis | No | Yes | |||

| AFP, ng/dL | < 400 | ≥ 400 | |||

Published in the late nineties, the Italian Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) score was calculated from the prognostic values of 435 patients originating from 16 centers (Tables 1 and 2)[4]. It includes other tumor-linked parameters such as portal vein thrombosis or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) serum levels and better estimates the liver function using the Child-Pugh score. Easy to calculate (4 variables to add), it is well correlated with survival (CLIP 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5-6: 42.5 vs 32 vs 16.5 vs 4.5 vs 2.5 vs 1.0 mo). The CLIP score was first assessed on a prospective cohort[5,6] and subsequently validated on Asian cohorts[7]. Still recently ranked first for its ability to predict survival[8], it was criticized for its lack of treatment offer, approximation in tumor morphology and extension, for the absence of clinical status consideration and its inability to classify intermediate stages. Another issue is that studies evaluating the CLIP system mainly included patients with scores only ranging from 0 to 2[7-9].

French speaking teams have created the GRETCH score in 1999. Quite similar to the CLIP, it further includes the patients’ overall condition but lacks tumor morphology information[10]. Also determined from a multivariate analysis including 761 patients (mainly non-treated) from 24 centers, it identifies 3 different groups (A: 0, B: 1 to 5 and C: 6 to 11 points) with distinct prognosis [overall survival after a year: A (72%), B (34%), C (7%), respectively]. Less evaluated than the CLIP, it faces the same limitations.

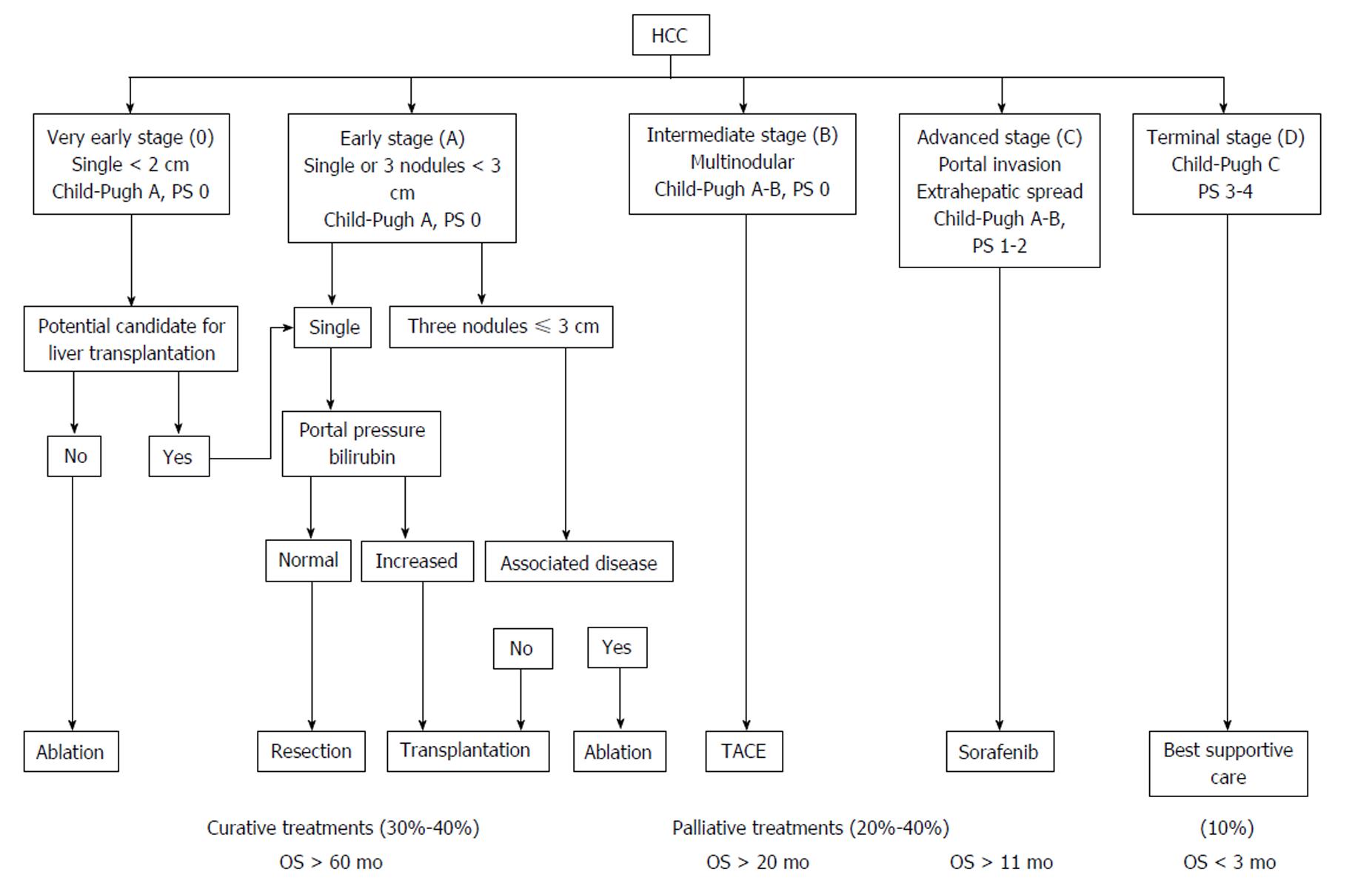

The BCLC classification was published at the same time[11]. Differently built as it is not based on a regression model but results from the combination of different studies, it distinguishes 4 different stages [A: (very) early, B: intermediate, C: advanced, D: terminal] with different prognosis, according to the liver function, the extent of the tumor and its consequences (Figure 2). As opposed to the previous scores, the early stages are well defined according to the number and size of nodules, the associated comorbidities and the portal vein pressure. The BCLC staging system was assessed on Western and Asian cohorts[12,13] and demonstrated a better ability to predict survival than most other scores[9,14]. This classification has imposed itself from its practical aspect and for being the only one linked to a treatment algorithm relying on a high level of evidence for each modality. Endorsed by both the European Associations for the Study of the Liver (EASL)[15] and the American Associations for the Study of the Liver (AASLD)[16], it has become the reference classification in Western countries and is being used in day-to-day practice and clinical trials.

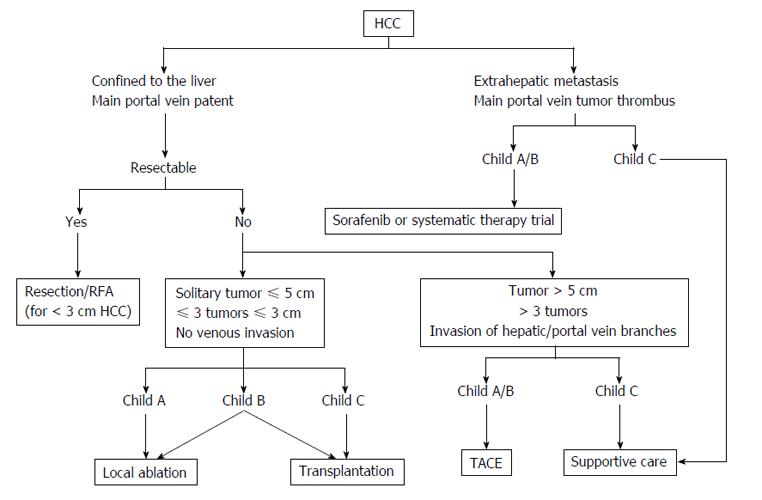

However, BCLC is not the reference classification in Asia, notably as HCC treatment modalities differ according to the countries (e.g., external radiotherapy, intra-arterial and systemic chemotherapy or TACE being indicated for advanced HCC despite a low level of evidence[17]). Such recommendations are based on studies but, as opposed to the BCLC, also rely on personal experience, experts advice and consensus conferences. Alternative scores or classifications have thus been proposed.

The Japan Integrated Staging (JIS) score was published in 2003 (Table 3)[18]. Also easy to calculate, it associates the Child-Pugh score and the Japanese TNM, which is based on three parameters (vascular invasion, unique vs multiple nodules, diameter ≤vs > 20 mm) determined from a population of 13772 operated patients. It defines six groups with different prognosis (excluding JIS 4-5). This score has demonstrated a better ability to predict survival than the CLIP and was further improved a few years later with the modified-JIS[19], in which the encephalopathy item is replaced by the indocyanine green clearance, due to an early HCC screening in Japan and a preferred surgical orientation. In 2008, the JIS score became the biomarker combined JIS with the inclusion of three HCC serum markers [AFP, AFP-L3 (AFP-Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive) and des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin], which allowed better survival predictions (Table 3)[20]. However, two of those markers are not frequently used in Western countries where HCC is also often being diagnosed at more advanced stages. Thus, this score, without treatment guidelines, has not been evaluated on patients from Western countries.

The Taipei Integrated Scoring system (TIS) was published in 2010[21] arised from the lack of a reference classification and the opposite results from studies regarding the performance of classification systems. TIS is a point scoring system combining AFP levels (< 400 vs > 400 ng/ml: 0 vs 1 point), Child-Pugh score (A, B and C : 0, 1 and 2 points, respectively) and the sum of the volume of each tumor (total tumor volume), calculated from the following formulae: [(4/3) × 3.14 × (radius of tumor in cm)3], and which defines 4 different groups (< 50 cm3, 50-250 cm3, 250-500 cm3, > 500 cm3: 0, 1, 2 or 3 points, respectively). From a cohort of 2030 patients, mainly with viral hepatitis (hepatitis B virus 51%, hepatitis C virus 27%), the score identified six distinct prognostic groups, with a score evolution inversely correlated to survival. The predictive ability of the TIS score was better than the JIS and the BCLC for the whole cohort, independently of the treatment modality (curative or palliative), but not as good as the CLIP for the 936 patients treated with curative intent. Vascular invasion that was observed in 36.7% of the patients is taken into account in the CLIP but not in the TIS, which probably participates in this discrepancy. Again, this score appears promising, but lacks a linkage to any treatment decision choice and has not been validated on any Western country patient.

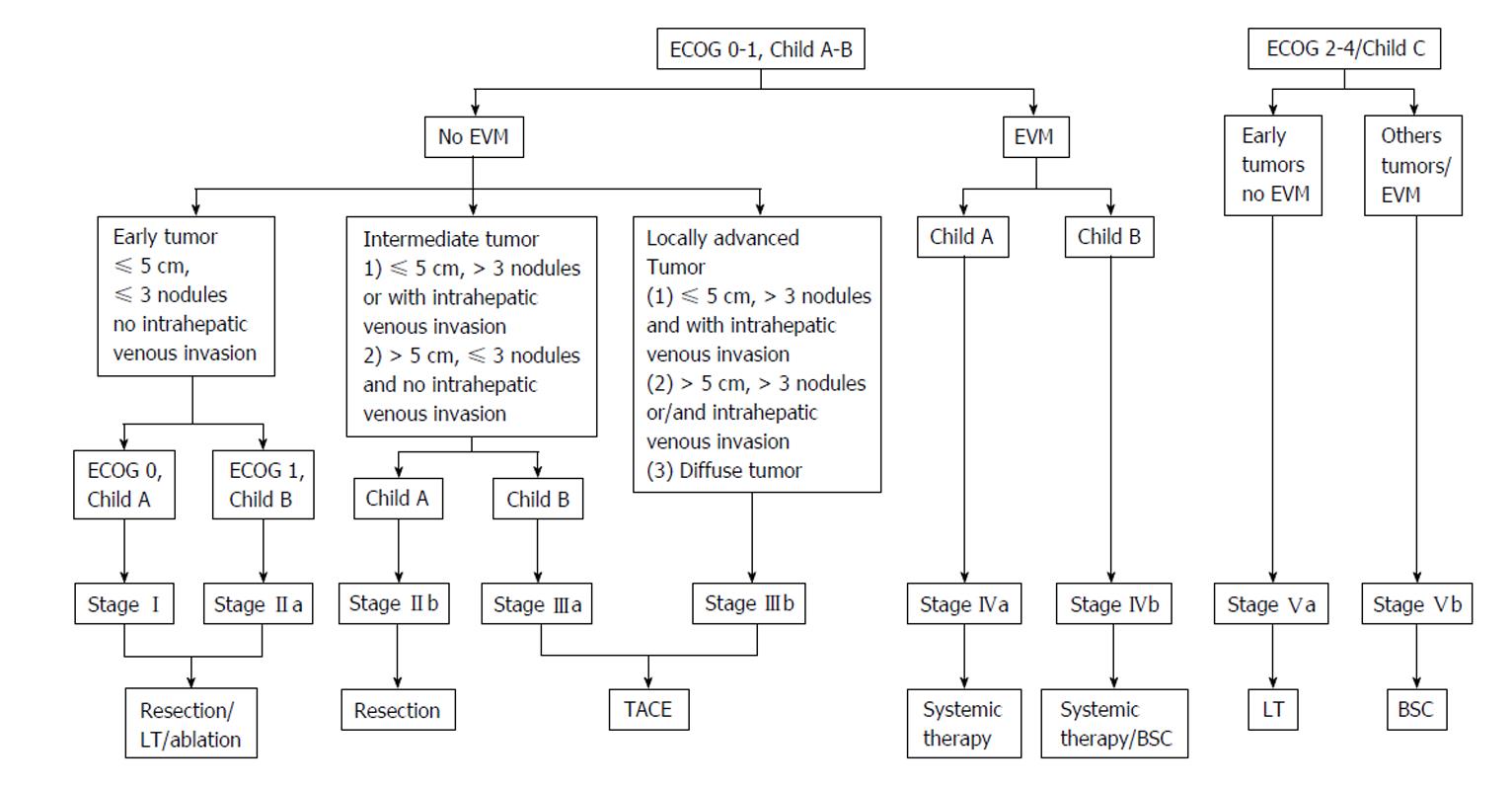

In 2011, an Asian experts meeting has suggested to adopt a common classification and common recommendations. TACE was then proposed for HCC with limited vascular invasion, despite a low level of evidence (Figure 3)[17]. The competing Hong Kong Liver Cancer (HKLC) classification, which is close to the BCLC system, was published in 2014[22]. Built from a population of 3856 patients (median age: 58 years old), mainly affected by viral hepatitis B, with Child-Pugh A scores (73%), it identifies five groups and nine sub-groups to further refine the prognosis (Figure 4). The associated treatment algorithm recommended surgery at more advanced stages and subsequently increased survival according to the authors. However, its prognostic value was comparable to the BCLC system for a European cohort of HCC linked to viral hepatitis C or alcohol, the IIa/IIb, IIIb/IVa, IVb/Vb subgroups presenting similar survival[23], which limits the impact of such a stratification within this population. A prospective study is currently on-going to further evaluate this score.

Overall, the BCLC classification has become the reference in Western countries and has replaced the other prognostic scores. Limitations have however been highlighted since several years. The intermediate BCLC B stage, which gathers multifocal tumors lacking vascular invasion and excludes unique and large HCC, now part of the BCLC A group in newer version of the BCLC classification[24], remains heterogeneous[25]. Thus, a diffuse multinodular HCC or four nodules of one centimeter in size within the same lobe are categorized within the same BCLC B group, and only a single therapeutic option is offered (i.e., chemoembolization). Advanced (BCLC C) stages encompass a broad spectrum of tumors, including cancers with or without symptoms, metastatic or locally advanced diseases, eventually associated with portal thrombosis, nodular or infiltrating tumors, uni- or multi-nodular tumors, associated with Child-Pugh A or B grade, which are, again, only associated with a single treatment (sorafenib)[24]. It has thus been suggested to extend the indication for surgery[26-28] or chemoembolization to some advanced stages[29,30]. Stage C HCC were defined using a population limited to 102 patients[31]. Furthermore, comparative studies have shown lower prognostic ability for the BCLC than the CLIP score regarding advanced HCC[32-34], and several studies have suggested a possible stratification for the BCLC C HCC[35-37]. For example, Yau et al[36] have proposed a new score called Advanced Liver Cancer Prognostic System (ALCPS), separating 3 groups according to their survival after 3 mo, and aiming at improving patients selection before their enrollment into clinical trials (Table 4). However, the ALCPS score is too complex for daily clinical practice as it includes eleven variables with different coefficients, as is the Chinese University Prognostic Index score[37].

| Parameters | Points |

| Ascites | 2 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 |

| Weight loss | 2 |

| Child-Pugh grade A/B/C | 0/2/5 |

| alkaline phosphatase, UI/L > 200 | 3 |

| Bilirubin, mcmol/L ≤ 33/> 33- ≤ 50/> 50 | 0/1/3 |

| Urea, mmol/L > 8.9 | 2 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 3 |

| Tumor size: Diffuse/> 5 cm/ ≤ 5 cm | 4/3/0 |

| Lung metastases | 3 |

| AFP, ng/mL > 400 | 4 |

| Probability of patients surviving at least 3 mo estimated by the ALCPS score[36] | |

| Score ≤ 8 points: 82.0% (95%CI: 76.5%-87.5%) | |

| Score 9-15 points: 53.4% (95%CI: 48.3%-57.7%) | |

| Score ≥ 16 points: 18.9% (95%CI: 14.7%-23.3%) |

Conversely, the recently published NIACE score[38] (Table 5) was determined from a population of advanced HCC and validated using an external Asian cohort, independently of the BCLC stage[39]. Easy to calculate and well correlated to survival, it distinguishes 2 subgroups with different prognosis within BCLC stage C patients. Advanced HCC are classified according to their morphology as infiltrating or diffuse (hardly delimited lesion, with a heterogeneous enhancement, more easily characterized using magnetic resonance imaging[40] and frequently associated with portal vein thrombosis[41] or bile duct invasion), as opposed to the nodular HCC meeting the EASL/AASLD diagnosis criteria[42]. It also considers the AFP level (± 200 ng/ml), whose prognostic value has been demonstrated independently of the stage of the disease[4,10,43]; those two last criteria missing from the BCLC system.

| Score NIACE | Points |

| Nodules < 3 | 0 |

| Nodules ≥ 3 | 1 |

| Infiltrative HCC: No | 0 |

| Infiltrative HCC: Yes | 1.5 |

| AFP < 200 ng/mL (at baseline) | 0 |

| AFP ≥ 200 ng/mL (at baseline) | 1.5 |

| Child-Pugh grade A | 0 |

| Child-Pugh grade B | 1.5 |

| ECOG PS 0 | 0 |

| ECOG PS ≥ 1 | 1.5 |

The predictive value of the NIACE score has been compared to those of the CLIP score and both the BCLC and HKLC classifications using a French multicenter HCC cohort of 1102 patients, of 68 (60-74) years of age, mostly with cirrhosis (81%), often linked to alcohol (41%) or hepatitis C (28%) or B (6%) viruses; most of the patients with Child-Pugh A and BCLC C scores, and treated according to the following modalities: Curative treatment in 22% of the cases (surgical resection or RFA), palliative treatment in 66% of the cases (TACE, sorafenib) and supportive care in 12% of the cases[44]. Each scoring system identified different prognosis subgroups (p < 0.0001), with scores and classifications correlated with survival. The NIACE score showed the best homogeneity (LR χ2 = 532.0369, p < 0.0001), the best discriminative ability (LT χ2 = 91.6906, p < 0.0001), the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC 10648.198) and the highest C-index [C-index 0.718 (0.688-0.748)] (Table 6). Using a threshold value of 1 or 2.5, the NIACE score identified 2 distinct prognosis groups within the CLIP 0, 1, 2 and 3 groups (p < 0.0001). As opposed to the HKLC, when applied to the various HKLC groups with similar survival (i.e., IIa/IIb, IIIb/IVa, IVb/Vb), the NIACE score highlighted 2 different prognosis subgroups using a threshold value of 3 (p < 0.0001). The same results were obtained when investigating the HKLC I group using a threshold value of 1 (p < 0.0001)[45].

| Score | Discriminatory ability linear trend test | Homogeneity likelihood ratio test | Akaike information criterion | C-index (95%CI) | ||

| LT (χ2) | P value | LR (χ2) | P value | |||

| NIACE | 91.6906 | < 0.0001 | 532.0369 | < 0.0001 | 10648.198 | 0.718 (0.688-0.748) |

| BCLC | 79.0342 | < 0.0001 | 380.4100 | < 0.0001 | 10805.825 | 0.674 (0.645-0.704) |

| HKLC | 71.8861 | < 0.0001 | 455.3169 | < 0.0001 | 10740.918 | 0.698 (0.673-0.731) |

| CLIP | 87.2785 | < 0.0001 | 430.3872 | < 0.0001 | 10749.848 | 0.716 (0.687-0.746) |

In conclusion, the use of additional prognostic scores improves the stratification of HCC selected according to the BCLC system.

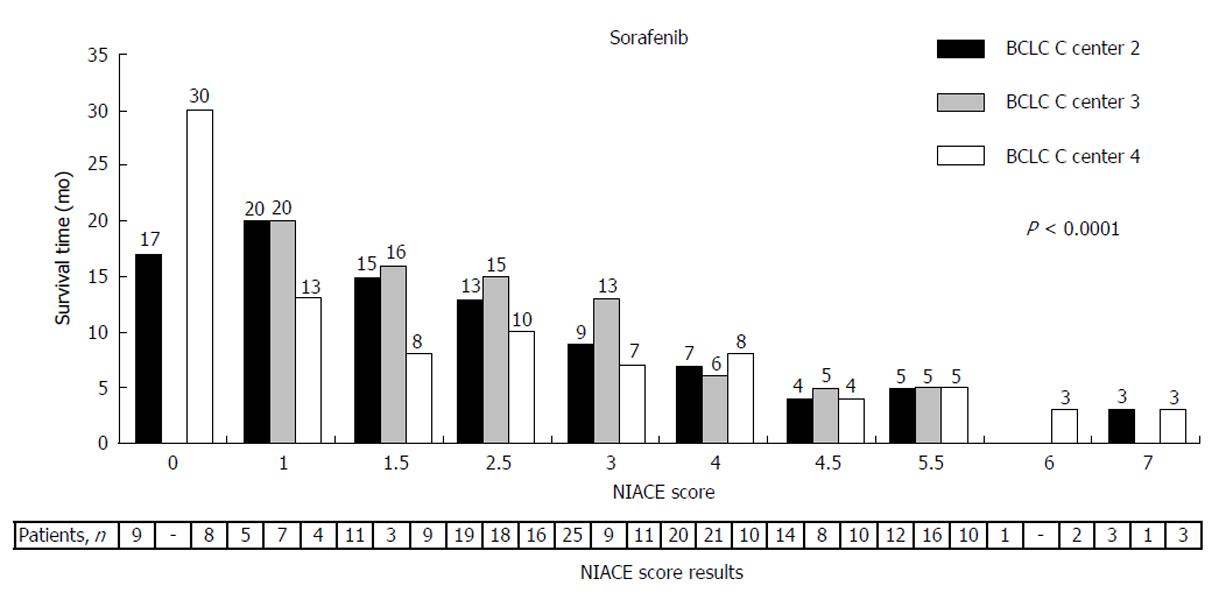

Sorafenib is recommended for BCLC stage C HCC[46,47] and is also a possible alternative for some BCLC stage B HCC being either progressive or confronted with chemoembolization contraindication[48]. The NIACE score allows to further stratify the BCLC stage C patients treated with sorafenib (Figure 5), by separating two distinct groups with different survival using a threshold value of 3[38]. The survival of patients with a NIACE score > 3 is limited to around 5.0 mo, despite a median treatment duration of 2 mo. Thus, this population does not seem to really benefit from the treatment and the NIACE score could be helpful in the treatment choice process or even earlier, to better classify patients before their enrollment into clinical trials.

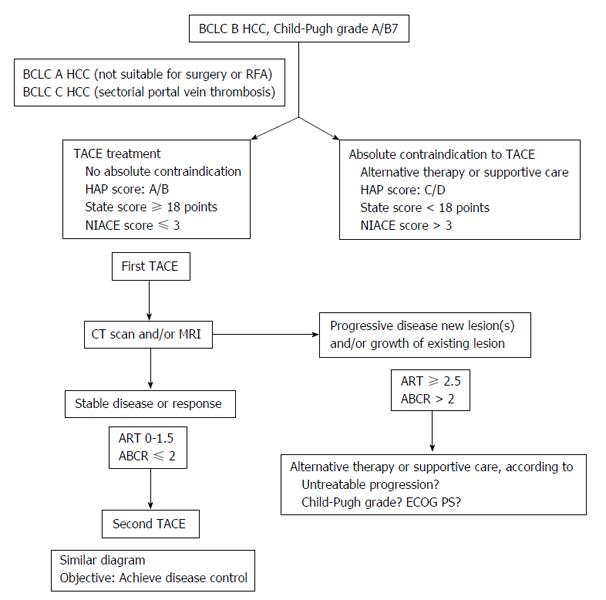

As chemoembolization is mainly recommended for intermediate BCLC stage B HCC[24], the usefulness of any additional prognostic score for such cases appears limited to some experts. However, if TACE remains the main treatment modality in most countries confronted with this disease[1], it is controversial. Its validation relies on two randomized studies with limited patients groups, mainly including intermediate and advanced HCC, and each offering a different treatment option[49,50]. Metadata analyses show contradictory results[51,52] and, despite the improvement of the selection criteria, the radiological response (according to the EASL or the mRECIST criteria)[53,54], the existing contraindications[55] or treatment termination criteria[56], there is still no consensus regarding the treatment strategy (on-demand or sequential), the number of treatments before reassessment[57], the overall aim (stability or response)[55,56] or concerning the TACE mode (using conventional techniques or calibrated drug-eluting beads). An additional score could thus facilitate the treatment strategy choice.

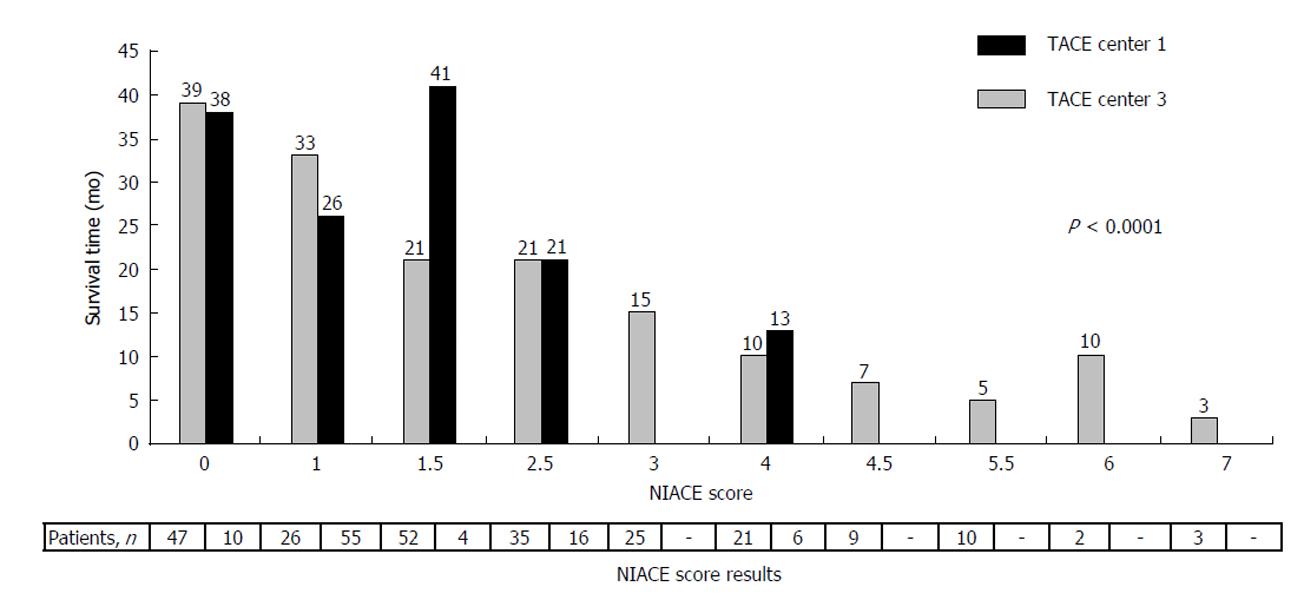

Several scores have been proposed recently to improve candidate patient selection (Table 7), as TACE is a potentially toxic treatment, with limited survival benefit. Among these pre-therapeutic scores, the Hepatoma Arterial-embolisation Prognostic (HAP) and the selection for transarterial chemoembolisation treatment (STATE) scores were determined from the prognostic variables of around a hundred of BCLC stage A, B (HAP, STATE) or even C (HAP) patients treated by TACE[58,59]. The NIACE score was also evaluated on two cohorts adding up 321 BCLC A, B or sometimes C (with distal portal vein thrombosis) patients treated by TACE. Using a threshold value of 3, the NIACE score identified two groups presenting a significantly different survival (NIACE ≤ 3:27 mo (24-31) vs NIACE > 3:7 mo (6-10), p < 0.0001), even without any stage C patients (Figure 6)[60]. It also separated two subgroups with distinct prognosis from an Asian cohort of patients treated by TACE[39], as opposed to the HAP score which failed to prove its ability to select all the “good” candidates for TACE from a multicenter European cohort (with similar survival between the subgroups)[61]. Such a result could be anticipated as the same rating (1 point) is attributed to each variable and only HCC > 70 mm are taken into account, whereas the efficiency of the TACE treatment relies on the size (generally < 50 mm) and the number of nodules. The more recent STATE score, which mainly focuses on multinodular (BCLC B) HCC, still needs to be evaluated. The list presented here is not exhaustive and some relatively new scores now include indocyanine green clearance to better evaluate the liver function before TACE[29], but often at the expense of simplicity, which should remain a priority.

| HAP (0 to 4 points) | NIACE (0 to 7 points) | STATE | ||

| Before the first TACE | ||||

| Albumin < 36 g/dL | 1 point | ≥ 3 nodules | 1 point | Albumin (g/L) |

| Bilirubin > 17 mcmol/L | 1 point | infiltrative HCC vs nodular HCC | 1.5 points | -12 (tumour load exceeding the up-to-7 criteria) |

| 0 | ||||

| AFP > 400 ng/mL | 1 point | AFP ≥ 200 ng/mL | 1.5 points | |

| Child-Pugh A vs Child-Pugh B | 0 | |||

| 1.5 points | ||||

| Size of dominant tumour > 70 mm | 1 point | ECOG PS ≥ 1 | 1.5 points | -12 (if CRP ≥ 1 mg/dL) |

| No chemoembolization | ||||

| ≥ 2 points | > 3 points | < 18 points | ||

The continuation of a TACE treatment is determined by the radiological response (which is correlated to survival after TACE[53]), a decrease in AFP levels and the impact of the treatment on the liver function.

After the first TACE: Two scores easy to calculate were proposed to improve the selection of patients before repeating the treatment: The Assessment for Retreatment with TACE (ART) and the ABCR scores, both defined using regression models[62,63]. The ART score associates its higher coefficient with a possible increase in ASAT levels (4 points), the lower being associated with the radiological response (1 point). It is recommended not to repeat the treatment in case of a score worsening ≥ 2.5 points (Table 8). Conversely, the ABCR system assigns a higher coefficient to the radiological response (-3 points), which is correlated to survival after TACE and to the initial stage of the disease (BCLC A/B/C: 0/2/3 points). The associated threshold value is a score worsening > 2 points. Both scores are usable after the second treatment. From a European multicenter cohort, the ART score calculated before the second or the third TACE failed to orientate the treatment option for all the patients[61,63]. If, unlike the ABCR, it did discriminate two different prognosis subgroups, the evolution of the ART score was not correlated with survival. As expected, patients with an ART score of 1 (i.e., no radiological response) presented a lower survival than the ART 4 (ASAT levels increase > 25%) patients. Among the ABCR score limitations stands the possible absence of radiological response after the first TACE, which affects almost 25% of the “late responders”, depending on the series[64]. The score being contributory after the second TACE, it is recommended to repeat the treatment in the absence of obvious progression and in case of worsening hepatic function.

| ART (0 to 8 points) | ABCR (-3 to 6 points) | ||

| Before the second, the third TACE….. | |||

| No radiological response | 1 point | AFP < 200 ng/mL | 0 |

| AFP ≥ 200 ng/mL | 1 point | ||

| AST increased > 25% | 4 points | BCLC A/B/C | 0/2/3 points |

| Child-Pugh increased: 1 point | 1.5 points | Child-Pugh increased ≥ 2 points | 2 points |

| Increased: ≥ 2 points | 3 points | Radiological response | -3 points |

| No chemoembolization | |||

| ART ≥ 2.5 points | ABCR > 2 points | ||

The prognostic ability of the ABCR score was higher than the HAP and ART systems on both Western[65] and Asian cohorts[66].

Overall, these pre-chemoembolization scores are not able to embrace all the patients or situations and cannot replace a multidisciplinary meeting. However, owing to the high number of patients treated following this modality, the heterogeneity of HCC and day-to-day practices, such scores could help in the therapy decision making process (Figure 7).

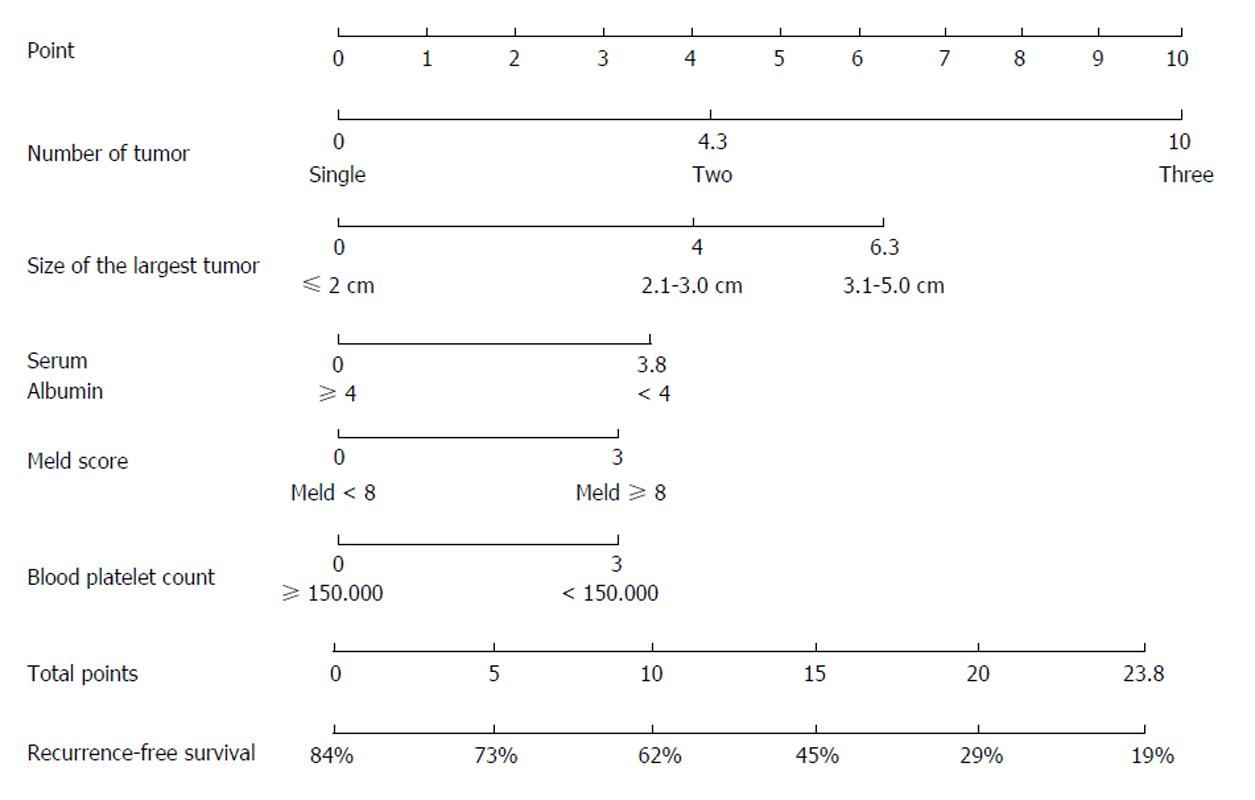

Surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation are curative treatments for HCC. In such cases, a score is not meant to exclude patients from the treatment when they meet the Barcelona criteria, early (BCLC A) stages being more homogeneous (single nodule or 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm), but to further evaluate their prognosis (overall survival and recurrence), in the prospect of a possible complementary treatment. This is illustrated by the nomogram recently proposed by Liu et al[67] which orientates stage A HCC towards surgery or RFA according to the risk of recurrence (Figure 8). However, some experts have proposed to extend the indication for surgery beyond the Barcelona criteria to some intermediate or advanced HCC, which are more heterogeneous[27]. Despite some interesting results, only a proper randomized comparative study could address this question using a prognostic score to improve patient classification.

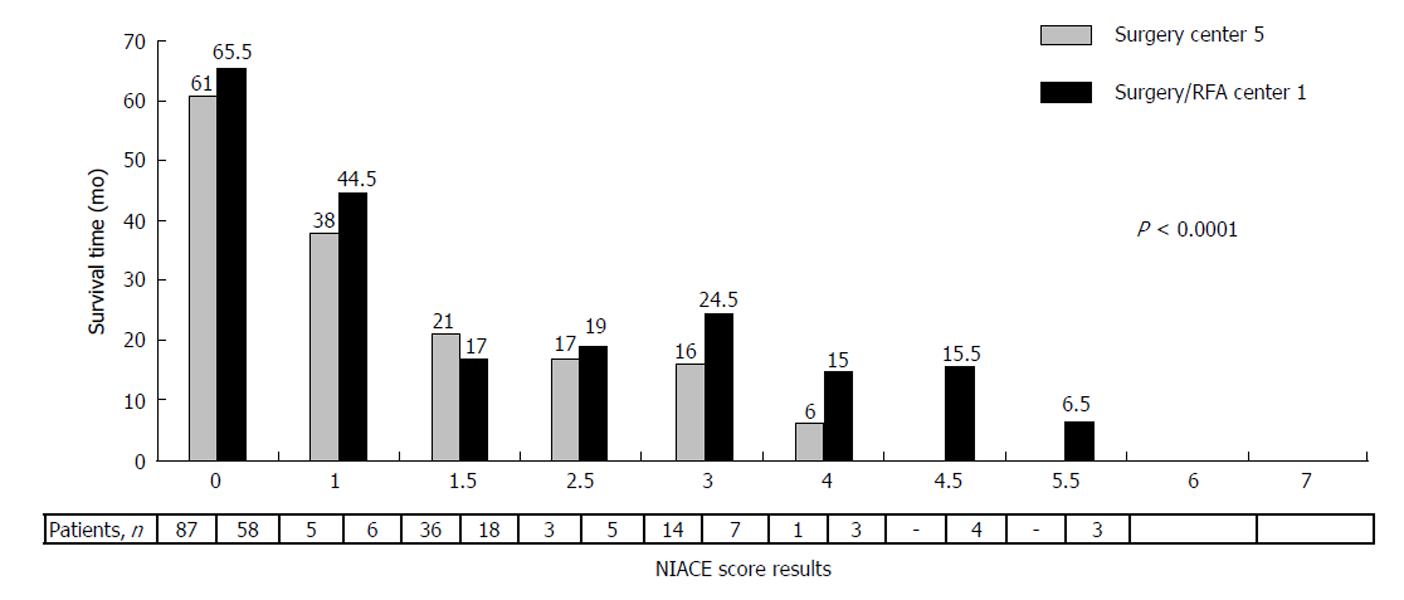

The NIACE score was tested on two French cohorts, both including around one hundred BCLC A/B and even C (single nodule with segmental portal vein thrombosis or above) HCC patients treated by surgery, thus beyond the scope of the BCLC recommendation, but in agreement with day-to-day practice. Using the more stringent threshold value of 1, it identified two different prognosis groups regarding the median overall survival (NIACE ≤ 1:61 mo (36-81) vs NIACE > 1:18 mo (9-73), p = 0.0005) and the mean time to progression (NIACE ≤ 1, 26.9 ± 16.3 mo vs NIACE > 1, 9.2 ± 9.7 mo, p < 0.0001)[68]. The score evolution was inversely correlated to survival (Figure 9). Similar results were observed using an Asian cohort comprising around one hundred BCLC A/B/C HCC patients treated by surgery[39].

When tested on a group of BCLC A HCC patients treated by surgery, selected from a French multicenter cohort, the NIACE score also highlighted two subgroups with distinct prognosis (median OS NIACE ≤ 1:80 (58-81) mo vs NIACE > 1:39 (28-58) mo, p = 0.0011), notably among patients with a single tumor exceeding 50 mm in the longest axis (median OS NIACE ≤ 1:80 (58-80) mo vs NIACE > 1:35 (18-58) mo, p = 0.0024)[44].

These results should be further confirmed by a prospective study but, again, an additional prognostic score could provide complementary information to the BCLC system.

HCC prognostic scores or classifications competed against each other until recently. A straightforward distribution and the corresponding treatment guide have allowed the BCLC classification to impose itself as the reference system in Western countries, and the HKLC system might do as well in Asian countries. However, owing to the heterogeneity of HCC, patients and daily practices, alternative scores such as NIACE, which includes different prognostic variables, could provide complementary tools to clinicians to better anticipate the disease evolution and optimize the stratification of patients within clinical trial or in the treatment decision making itself.

P- Reviewer: Cerwenka HR, Frenette C, Johnson PJ S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, Kudo M, Johnson P, Wagner S, Orsini LS. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int. 2015;35:2155-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 945] [Article Influence: 94.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kee KM, Wang JH, Lee CM, Chen CL, Changchien CS, Hu TH, Cheng YF, Hsu HC, Wang CC, Chen TY. Validation of clinical AJCC/UICC TNM staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of 5,613 cases from a medical center in southern Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:2650-2655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Obata H, Tomimatsu M, Okazaki N, Hasegawa H, Nakajima Y, Ohnishi K. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment. Study of 850 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:918-928. [PubMed] |

| 4. | A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28:751-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 977] [Cited by in RCA: 963] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Prospective validation of the CLIP score: a new prognostic system for patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) Investigators. Hepatology. 2000;31:840-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Prospective validation of the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) score: a new prognostic system for patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2000;32:679-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ueno S, Tanabe G, Sako K, Hiwaki T, Hokotate H, Fukukura Y, Baba Y, Imamura Y, Aikou T. Discrimination value of the new western prognostic system (CLIP score) for hepatocellular carcinoma in 662 Japanese patients. Cancer of the Liver Italian Program. Hepatology. 2001;34:529-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu PH, Hsu CY, Hsia CY, Lee YH, Su CW, Huang YH, Lee FY, Lin HC, Huo TI. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: Assessment of eleven staging systems. J Hepatol. 2016;64:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cillo U, Vitale A, Grigoletto F, Farinati F, Brolese A, Zanus G, Neri D, Boccagni P, Srsen N, D’Amico F. Prospective validation of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system. J Hepatol. 2006;44:723-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chevret S, Trinchet JC, Mathieu D, Rached AA, Beaugrand M, Chastang C. A new prognostic classification for predicting survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Groupe d’Etude et de Traitement du Carcinome Hépatocellulaire. J Hepatol. 1999;31:133-141. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2645] [Cited by in RCA: 2876] [Article Influence: 110.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, Askari F, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology. 2005;41:707-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang JH, Changchien CS, Hu TH, Lee CM, Kee KM, Lin CY, Chen CL, Chen TY, Huang YJ, Lu SN. The efficacy of treatment schedules according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging for hepatocellular carcinoma - Survival analysis of 3892 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1000-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Pachera S, Valdegamberi A, Sandri M, D’Onofrio M, Iacono C. Comparison of seven staging systems in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort of patients who underwent radiofrequency ablation with complete response. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:597-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodés J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421-430. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Bruix J, Sherman M, Practice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4333] [Cited by in RCA: 4508] [Article Influence: 225.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Han KH, Kudo M, Ye SL, Choi JY, Poon RT, Seong J, Park JW, Ichida T, Chung JW, Chow P. Asian consensus workshop report: expert consensus guideline for the management of intermediate and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Oncology. 2011;81 Suppl 1:158-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kudo M, Chung H, Osaki Y. Prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma (CLIP score): its value and limitations, and a proposal for a new staging system, the Japan Integrated Staging Score (JIS score). J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 501] [Cited by in RCA: 538] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ikai I, Takayasu K, Omata M, Okita K, Nakanuma Y, Matsuyama Y, Makuuchi M, Kojiro M, Ichida T, Arii S. A modified Japan Integrated Stage score for prognostic assessment in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:884-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kitai S, Kudo M, Minami Y, Ueshima K, Chung H, Hagiwara S, Inoue T, Ishikawa E, Takahashi S, Asakuma Y. A new prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma: value of the biomarker combined Japan integrated staging score. Intervirology. 2008;51 Suppl 1:86-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hsu CY, Huang YH, Hsia CY, Su CW, Lin HC, Loong CC, Chiou YY, Chiang JH, Lee PC, Huo TI. A new prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma based on total tumor volume: the Taipei Integrated Scoring System. J Hepatol. 2010;53:108-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yau T, Tang VY, Yao TJ, Fan ST, Lo CM, Poon RT. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1691-1700.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Bronowicki JP, Raoul JL. Usefulness of the HKLC vs. the BCLC staging system in a European HCC cohort. J Hepatol. 2015;62:492-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4059] [Cited by in RCA: 4521] [Article Influence: 347.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Bolondi L, Burroughs A, Dufour JF, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, Raoul JL, Sangro B. Heterogeneity of patients with intermediate (BCLC B) Hepatocellular Carcinoma: proposal for a subclassification to facilitate treatment decisions. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:348-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chang WT, Kao WY, Chau GY, Su CW, Lei HJ, Wu JC, Hsia CY, Lui WY, King KL, Lee SD. Hepatic resection can provide long-term survival of patients with non-early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: extending the indication for resection? Surgery. 2012;152:809-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, Takayama T, Capussotti L, Nuzzo G, Vauthey JN, Choti MA, De Santibanes E, Donadon M. A snapshot of the effective indications and results of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in tertiary referral centers: is it adherent to the EASL/AASLD recommendations?: an observational study of the HCC East-West study group. Ann Surg. 2013;257:929-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, Trevisani F, Farinati F, Spolverato G, Volk M, Giannini EG, Ciccarese F, Piscaglia F. Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:617-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Xu L, Peng ZW, Chen MS, Shi M, Zhang YJ, Guo RP, Lin XJ, Lau WY. Prognostic nomogram for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. J Hepatol. 2015;63:122-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xue TC, Xie XY, Zhang L, Yin X, Zhang BH, Ren ZG. Transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: a meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, Vilana R, Ayuso Mdel C, Sala M, Brú C, Rodés J, Bruix J. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology. 1999;29:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 839] [Cited by in RCA: 907] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Huitzil-Melendez FD, Capanu M, O’Reilly EM, Duffy A, Gansukh B, Saltz LL, Abou-Alfa GK. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: which staging systems best predict prognosis? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2889-2895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Collette S, Bonnetain F, Paoletti X, Doffoel M, Bouché O, Raoul JL, Rougier P, Masskouri F, Bedenne L, Barbare JC. Prognosis of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of three staging systems in two French clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1117-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang JF, Shu ZJ, Xie CY, Li Q, Jin XH, Gu W, Jiang FJ, Ling CQ. Prognosis of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of seven staging systems (TNM, Okuda, BCLC, CLIP, CUPI, JIS, CIS) in a Chinese cohort. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhao Y, Wang WJ, Guan S, Li HL, Xu RC, Wu JB, Liu JS, Li HP, Bai W, Yin ZX. Sorafenib combined with transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a large-scale multicenter study of 222 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1786-1792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yau T, Yao TJ, Chan P, Ng K, Fan ST, Poon RT. A new prognostic score system in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma not amendable to locoregional therapy: implication for patient selection in systemic therapy trials. Cancer. 2008;113:2742-2751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Leung TW, Tang AM, Zee B, Lau WY, Lai PB, Leung KL, Lau JT, Yu SC, Johnson PJ. Construction of the Chinese University Prognostic Index for hepatocellular carcinoma and comparison with the TNM staging system, the Okuda staging system, and the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program staging system: a study based on 926 patients. Cancer. 2002;94:1760-1769. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Adhoute X, Pénaranda G, Raoul JL, Blanc JF, Edeline J, Conroy G, Perrier H, Pol B, Bayle O, Monnet O. Prognosis of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a new stratification of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C: results from a French multicenter study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:433-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Su TH, Liu CJ, Yang HC, Liu CH, Chen PJ, Chen DS. The NIACE score helps predict the survival of Asian hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:23. |

| 40. | Rosenkrantz AB, Lee L, Matza BW, Kim S. Infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of MRI sequences for lesion conspicuity. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:e105-e111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Benvegnù L, Noventa F, Bernardinello E, Pontisso P, Gatta A, Alberti A. Evidence for an association between the aetiology of cirrhosis and pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma development. Gut. 2001;48:110-115. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Bruix J, Sherman M, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6573] [Article Influence: 469.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Ochiai T, Sonoyama T, Ichikawa D, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Sakakura C, Ueda Y, Otsuji E, Itoi H, Hagiwara A. Poor prognostic factors of hepatectomy in patients with resectable small hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:197-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Raoul JL, Bourlière M. Hepatocellular carcinoma scoring and staging systems. Do we need new tools? J Hepatol. 2016;64:1449-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Raoul JL, Bourlière M. “Staging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: BCLC system, what else!”. Liver Int. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10271] [Article Influence: 604.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 47. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3854] [Cited by in RCA: 4653] [Article Influence: 273.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Bruix J, Raoul JL, Sherman M, Mazzaferro V, Bolondi L, Craxi A, Galle PR, Santoro A, Beaugrand M, Sangiovanni A. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: subanalyses of a phase III trial. J Hepatol. 2012;57:821-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 664] [Cited by in RCA: 655] [Article Influence: 50.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, Fan ST, Wong J. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1904] [Cited by in RCA: 1987] [Article Influence: 86.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, Ayuso C, Sala M, Muchart J, Solà R. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734-1739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2502] [Cited by in RCA: 2611] [Article Influence: 113.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Oliveri RS, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Transarterial (chemo)embolisation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD004787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2207] [Cited by in RCA: 2271] [Article Influence: 103.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Gillmore R, Stuart S, Kirkwood A, Hameeduddin A, Woodward N, Burroughs AK, Meyer T. EASL and mRECIST responses are independent prognostic factors for survival in hepatocellular cancer patients treated with transarterial embolization. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1309-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kim BK, Kim KA, Park JY, Ahn SH, Chon CY, Han KH, Kim SU, Kim MJ. Prospective comparison of prognostic values of modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours with European Association for the Study of the Liver criteria in hepatocellular carcinoma following chemoembolisation. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:826-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Raoul JL, Sangro B, Forner A, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, Bolondi L, Lencioni R. Evolving strategies for the management of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: available evidence and expert opinion on the use of transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:212-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Bruix J, Reig M, Rimola J, Forner A, Burrel M, Vilana R, Ayuso C. Clinical decision making and research in hepatocellular carcinoma: pivotal role of imaging techniques. Hepatology. 2011;54:2238-2244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Wang W, Zhao Y, Bai W, Han G. Response assessment for HCC patients treated with repeated TACE: The optimal time-point is still an open issue. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1530-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Kadalayil L, Benini R, Pallan L, O’Beirne J, Marelli L, Yu D, Hackshaw A, Fox R, Johnson P, Burroughs AK. A simple prognostic scoring system for patients receiving transarterial embolisation for hepatocellular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2565-2570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hucke F, Pinter M, Graziadei I, Bota S, Vogel W, Müller C, Heinzl H, Waneck F, Trauner M, Peck-Radosavljevic M. How to STATE suitability and START transarterial chemoembolization in patients with intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1287-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Raoul JL, Perrier H, Castellani P, Conroy G. Hepatocellular carcinoma, NIACE score: an aid to the decision-making process before the first transarterial chemoembolization. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:339-340. |

| 61. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Castellani P, Perrier H, Bourliere M. Recommendations for the use of chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Usefulness of scoring system? World J Hepatol. 2015;7:521-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Sieghart W, Hucke F, Pinter M, Graziadei I, Vogel W, Müller C, Heinzl H, Trauner M, Peck-Radosavljevic M. The ART of decision making: retreatment with transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57:2261-2273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Naude S, Raoul JL, Perrier H, Bayle O, Monnet O, Beaurain P, Bazin C, Pol B. Retreatment with TACE: the ABCR SCORE, an aid to the decision-making process. J Hepatol. 2015;62:855-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Georgiades C, Geschwind JF, Harrison N, Hines-Peralta A, Liapi E, Hong K, Wu Z, Kamel I, Frangakis C. Lack of response after initial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: does it predict failure of subsequent treatment? Radiology. 2012;265:115-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Castellani P, Perrier H, Naude S, Monnet M. Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treated by chemoembolisazation. What prognostic score use: ART, HAP, ABCR? A comparative French multicenter study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:178-179. |

| 66. | Yang H, Bae SH, Lee S, Lee HL, Jang JW, Choi JY. Korean validation and comparison of prognostic scores for transarterial chemoembolization: ART, ABCR, HAP and modified HAP. Hepatology. 2015;62:437A. |

| 67. | Liu PH, Hsu CY, Lee YH, Hsia CY, Huang YH, Su CW, Chiou YY, Lin HC, Huo TI. When to Perform Surgical Resection or Radiofrequency Ablation for Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma?: A Nomogram-guided Treatment Strategy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Raoul JL, Pol B, Bollon E, Perrier H. Hepatocellular carcinoma, NIACE score: A simple tool to better distinguish patients at risk of relapse after surgery. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:341. |