Published online Apr 8, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i4.710

Peer-review started: August 2, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: December 15, 2014

Accepted: January 30, 2015

Article in press: February 2, 2015

Published online: April 8, 2015

Processing time: 256 Days and 3.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the etiology and management of a poorly understood complication of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; “endotipsitis”.

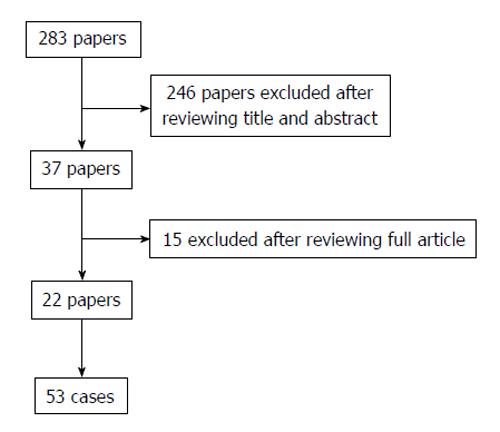

METHODS: A MEDLINE database search was carried out, reviewing all papers with specific words in the title or abstract, and excluding appropriately. Of 283 papers that were reviewed, 22 papers reporting 53 cases in total were included in the analyses.

RESULTS: No predominant etiology for endotipsitis was identified, but gram-positive organisms were more common among early-onset infections (P < 0.01). A higher mortality rate was associated with Staphylococcus aureus and Candida spp infections (P < 0.01). There was no trend in choice of antibiotic based on the microorganisms isolated and treatment varied from the guidelines of other vegetative prosthetic infections. In endotipsitis “high risk” organisms have been identified, emphasizing the importance of ensuring optimal antimicrobial therapy and adjunctive management strategies.

CONCLUSION: Higher mortality rate was associated with Staphylococcus aureus and Candida spp infections. A prospective multicenter trial is needed before specific treatment can be recommended.

Core tip: We present a case of a rare disease entity called endotipsitis, vegetative infection of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). This case has the longest latency, from insertion to infection, reported in the literature. The literature review supplementing this case report demonstrates an association between onset of infection from TIPS insertion and the etiological agent causing the disease. Furthermore, we demonstrate significantly poorer outcomes in specific infections.

- Citation: Navaratnam AM, Grant M, Banach DB. Endotipsitis: A case report with a literature review on an emerging prosthetic related infection. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(4): 710-716

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i4/710.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i4.710

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) insertion is a minimally invasive procedure that is used for the decompression of elevated portal pressure. Technical complications to this procedure include capsular perforation affecting up to 33% of cases, with 1%-2% leading to significant intraperitoneal haemorrhage as well as stent misplacement in 20% of cases[1]. Although initially employed to treat refractory variceal bleeding and ascites, its list of indications has broadened[2]. Increasing experience with this procedure has led to the recognition of multiple complications including hepatic failure, encephalopathy, sepsis and death. Sustained or relapsing bacteraemia secondary to endovascular vegetative infection of the prosthesis is a rare but serious complication[3].

In 1998, Sanyal et al[3] proposed the term “endotipsitis” to describe this disease entity, along with a proposal for diagnostic criteria[4]. They defined a “definite” infection as continuous clinically significant bacteraemia with vegetative/thrombi inside TIPS and “probable” infection sustained bacteraemia with no other source of infection in a patient with TIPS[3]. Since this proposal, there have been several suggestions to improve the diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity of the disease.

Incidence and risk factors of endotipsitis are poorly understood due to difficulty in diagnosis and lack of a uniform disease definition[2]. There are no extensive studies on this topic, the most recent and thorough being a single centre, retrospective study in 2010, which found the incidence of endotipsitis in patients with TIPS to be approximately 1%[3]. Furthermore, no unified agreement on the best management strategy for these cases to prevent relapses or mortality has been reached. The authors report a case of endotipsitis supplemented with an analysis on a literature review of this disease process and antimicrobial therapy.

In July 2013 a 30-year-old male with a history of intravenous drug use, chronic liver disease secondary to congenital hepatic fibrosis and alcohol dependence presented with a one month history of fevers, weakness, confusion and rigors. He described a four day history of intermittent stabbing right-sided abdominal pain, non-productive cough, headache and constant fever - all of which had been gradually worsening. He also reported a three-week history of worsening peripheral edema treated with furosemide and spironolactone. Two days before his admission his family noted confusion and impaired cognitive function.

His past medical history also included resection of a right hepatic lobe mesenchymal hemangioma at age 6, non-bleeding esophageal varices, TIPS insertion 38 mo prior to admission and splenic artery embolization to ameliorate hypersplenism. TIPS insertion was carried out in an elective setting to prevent esophageal variceal bleeds.

On examination, there was evidence of tender hepatomegaly and right flank tenderness. Although his abdomen was distended, there was no evidence of shifting dullness. He had track marks secondary to injections on both arms, symmetrical peripheral edema and tattoos on his back and arms. No abnormalities were found on neurological examination, other than impaired cognition.

Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 10.7 × 109/L with 86% neutrophils, hemoglobin of 93 g/L, platelet count of 63 × 109/L, aspartate transaminase 819 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 148 U/L, alkaline phosphatase of 2210 U/L, total bilirubin of 23.4 mg/dL (19.8 direct) and a markedly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 111 mm/h. Blood cultures drawn at admission grew both Klebsiella oxytoca, only resistant to ampicillin, and Escherichia coli (E. coli) (resistant to ampicillin and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim).

He was initially treated with piperacillin-tazobactam and gentamicin. Diagnostic workup included doppler ultrasound of the liver showing a patent TIPS with markedly decreased velocity at the portal aspect (17 cm/s, decreased from 104 cm/s two years prior), and computed tomography imaging revealed a non-occlusive filling defect in the superior segment of the TIPS. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation but no vegetations were seen.

The patient slowly improved despite blood cultures remaining persistently positive for six days and fever continuing for nine days despite appropriate treatment. He subsequently completed a six-week course of combination intravenous antibiotic therapy, at which point antibiotics were changed to oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg daily. In light of the high risk and complication of relapsing bacteraemia and inability to remove the suspected infected TIPS, the relatively inexpensive and well tolerated use of suppressive oral ciprofloxacin was decided until transplant. He was followed for the next 14 mo without infection relapse. Unfortunately the patient was lost to follow up, so was not possible to conduct repeat imaging.

We performed a MEDLINE database search, January 1956 to November 2013, using terms “infection”, “vegetation”, “bacteraemia”, “sepsis”, “tipsitis” and “endotipsitis” combined with the term transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, TIPSS or TIPs. The titles and abstracts of all papers that appeared on this search were reviewed and excluded accordingly. All data was entered in Microsoft Excel spreadsheet software. Univariate analysis was performed using a χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Data was analyzed in SPSS, version 16.0[4]. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our literature search produced 283 papers, 246 of which were excluded on the basis of their title and abstract. Of the 37 remaining articles, another 15 were excluded after reviewing the contents of the full article. There were 22 papers that reported a sum of 53 cases of “endotipsitis”; 15 case reports and 7 case series (Figure 1). Based on the demographics of the cases, including, age, gender, co-morbidities and aetiological agent, it was possible to exclude any duplications. Analysis includes the case reported by the authors.

The mean age was 54.3 years (range 30-69 years; 14 cases unrecorded), with a predominance of males (70.4% vs 17%). The most common underlying disease process was alcoholic liver disease (n = 32), 6 of which were also positive for hepatitis B (HBV) (n = 1), hepatitis C virus (HCV) (n = 4) or both (n = 1). HCV cirrhosis (n = 10) was the second most common etiology of chronic liver disease, followed by cryptogenic cirrhosis (n = 9), HBV (n = 1), primary sclerosing cholangitis (n = 1) and one case was not recorded. There was no record of whether viral hepatitis positive cases were undergoing treatment at the time of diagnosis of endotipsitis.

Of the 54 cases (including our case report); there were 30 monomicrobial gram-positive infections [of which 14 were Enterococcal spp and 7 were Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)], 11 monomicrobial gram-negative infections (of which 6 were E. coli), 5 polymicrobial and 6 Candida spp infections (4 Candida glabrata and 2 Candida albicans). The mean onset of endotipsitis from insertion of TIPS was 277 d, with bacterial being 304 d, and the longest overall being our case report 1158 d (range 6-158 d; 3 unrecorded). Among monomicrobial bacterial infections gram-positive organisms were significantly more common in early-onset infections (less than 120 d following TIPS insertion) than late-onset infections [18/19, (94.7%) vs 9/18 (50%) P < 0.01]. The average duration of bacteraemia was 43 d (range 3-20 d; 14 unrecorded).

Of the 54 cases reported, 30 (56%) were treated successfully with antimicrobials, 4 (7%) underwent transplantation and 17 (31%) died (Table 1). The average duration of treatment for fungemia and bacteremia was 28 (range 6-51 wk, 3 unrecorded) and 13.5 (range 1-101 wk; 10 unrecorded) wk respectively. Of those with bacteremia, 25 cases were treated with a single antibiotic (19 cases resolved; 2 outcome not recorded), where as 14 were managed with combination antibiotic therapy (1 case patient received 6 different antibiotics; 8 cases resolved). Comparing gram-positive and gram-negative infections, there was no significant difference in mortality [9/30 (30%) vs 4/12 (33%), P = 0.57]. Of the 39 antibiotic therapies recorded for bacterial endotipsitis, 7 cases used an aminoglycoside (gentamicin) and 2 used rifampin. None of the staphylococcal cases were treated with gentamicin.

| Etiological agent | Outcome | Duration ofbacteremia (d) | Treatment | Duration of treatment (wk) | Cirrhosis etiology | Onset (d) | Ref. |

| Gram positive, monomicrobial infections | |||||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | R | 6 | Vancomycin Rifampin | 6 | EtOH | 110 | [3] |

| Tx | - | - | - | HCV | 38 | [17] | |

| D | 15 | Ciprofloxacin Penicillin Vancomycin Teicoplanin Rifampin | 9 | HCV | 8 | [6] | |

| D | - | Flucloxacillin | 2 | EtOH | 663 | [2] | |

| D | 5 | Vancomycin | 1 | EtOH, HBV, HCV | 100 | [18] | |

| D | - | - | - | HCV | 38 | [17] | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | R | 46 | Vancomycin Linezolid | 6 | Cryptogenic | 300 | [5] |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | R | 25 | Daptomycin | 6 | EtOH | 7 | [19] |

| R | 30 | Vancomycin | 6 | EtOH | 120 | [5] | |

| Enterococcus spp. (unspecified) | R | 14 | Vancomycin | 6 | Cryptogenic | 47 | [5] |

| R | 10 | Vancomycin Gentamicin | 28 | EtOH, HCV | 10 | [20] | |

| R | 3 | Vancomycin Gentamicin | 2 | EtOH | 60 | [18] | |

| R | 21 | Vancomycin | 7 | HCV | - | [20] | |

| D | - | Vancomycin | - | EtOH | 60 | [20] | |

| Tx | - | - | - | HCV | 38 | [20] | |

| D | - | - | - | HCV | 38 | [20] | |

| D | - | - | - | HCV | 38 | [20] | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | R | 90 | Gentamicin Amphotericin | 6 | EtOH | 420 | [21] |

| R | 100 | Quinupristin | 14 | Cryptogenic | - | [22] | |

| R | 10 | Vancomycin | 8 | Cryptogenic | 60 | [23] | |

| Tx | 10 | Vancomycin | 4 | Cryptogenic | 90 | [16] | |

| Enterococcus faecium | R | 10 | Vancomycin | 28 | EtOH | 10 | [20] |

| - | - | Vancomycin | 1 | EtOH | 375 | [2] | |

| Streptococcus sanguis | R | 6 | Penicillin | 4 | EtOH | 416 | [3] |

| Gemella morbillorum | R | 5 | Vancomycin | 2 | PSC | 6 | [18] |

| R | 60 | Ampicillin | 44 | EtOH | 56 | [24] | |

| Streptococcus bovis | R | 6 | Vancomycin | 6 | Cryptogenic | 416 | [3] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | R | - | Netilmicin, Clarithromycin | 12 | EtOH | 730 | [2] |

| Lactobacillus acidophillus | D | 4 | Ampicillin | 4 | EtOH | 732 | [18] |

| D | 3 | Ampicillin Gentamicin | 6 | EtOH | 146 | [18] | |

| Gram negative, monomicrobial infections | |||||||

| Escherichia coli | R | 6 | Ceftriaxone | 4 | EtOH | 183 | [3] |

| R | 6 | Ceftriaxone | 4 | EtOH | 532 | [3] | |

| R | 31 | Ciprofloxacin | 16 | EtOH | 1065 | [6] | |

| D | - | Ceftriaxone | 12 | EtOH | 282 | [2] | |

| Gentamicin | |||||||

| D | - | Ceftriaxone Vancomycin Piperacillin-Tazobactam Amoxicillin | 12 | EtOH | 1092 | [2] | |

| D | - | Meropenem Amikacin | 3 | EtOH | 765 | [2] | |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | R | 6 | Ceftriaxone | 4 | EtOH, HCV | 329 | [3] |

| Klebsiella (unspecified) MDR | R | 9 | Tigecycline | - | EtOH | 1095 | [25] |

| Serratia marcescens | R | 49 | Imipenem | 98 | EtOH | 21 | [26] |

| Enterobacter cloacae | R | - | Ceftriaxone Gentamicin Vancomycin Piperacillin-Tazobactam Meropenem Ciprofloxacin | 12 | EtOH | 1065 | [2] |

| Salmonella typhi | - | - | - | - | - | - | [27] |

| Fungal infections | |||||||

| Candida glabrata | R | 1700 | Amphotericin | 51 | HCV | 180 | [28] |

| D | 27 | Amphotericin | 27 | Cryptogenic | 27 | [29] | |

| D | - | Fluconazole | - | EtOH | 150 | [30] | |

| D | 60 | Posaconazole | 6 | EtOH | - | [31] | |

| Candida albicans | R | - | - | - | HBV | 38 | [18] |

| D | - | - | - | HCV | 38 | [18] | |

| Polymicrobial infections | |||||||

| Staphylococcus aureus/Pseudomonas aeruginosa | D | 14 | Ticarcillin-clavulanic acid Gentamicin Amikacin Ciprofloxacin | - | EtOH, HBV | 35 | [6] |

| Escherichia coli/Klebsiella oxytoca | R | 6 | Ceftriaxone | 4 | EtOH | 235 | [3] |

| Escherichia coli/Acinetobacter | R | 6 | Ceftriaxone | 6 | EtOH | 285 | [3] |

| Escherichia coli/Klebsiella oxytoca | R | 6 | Piperacillin-Tazobactam Gentamicin | 6 | Cryptogenic, EtOH | 1158 | - |

| “Polymicrobial” | R | 720 | - | 101 | HCV | 100 | [32] |

| “Polymicrobial” | Tx | 90 | - | - | HCV | 180 | [15] |

| Unknown | - | - | - | - | - | - | [2] |

The organisms associated with the highest mortality rates were S. aureus (63% mortality) and Candida spp (67% mortality). Patients with infections caused by S. aureus and Candida spp had significantly higher mortality than those infections caused by all other organisms [9/14 (64.3%) vs 8/36 (22.2%) P < 0.01]. There was no difference in mortality rate between early and late-onset infections [8/22 (36.4%) vs 7/23 (30.4%) P = 0.67].

The authors have reported a case of Klebsiella oxytoca and E. coli polymicrobial endotipsitis with the longest latency of time between TIPS insertion and TIPS infection ever reported. A case of endotipsitis with similar bacteriology was reported previously but was managed quite differently (ceftriaxone monotherapy for 4 wk). Our literature review reviews the largest number of reported endotipsitis cases to date and provides a window into a rare disease, heterogeneous in both its microbiologic etiology and management approaches.

Endotipsitis is suspected in the setting of unexplained bacteremia in a patient with TIPS, supported by abnormalities in TIPS flow or the presence of vegetation and remains a diagnosis of exclusion, but there have been propositions to improve the diagnostic accuracy. Bouza et al[5] suggested using quantitative bacteriology, where by comparison of colony counts of peripheral venous blood and portal blood will show a substantial increase in bacteria of the latter sample. The gold standard would be to take a biopsy from the pseudo-epithelium of the TIPS, which can only be done at autopsy or after transplantation and is therefore not a viable option in clinical practice[6].

It is evident from our review that no single microorganism is the predominant etiological agent, but most infections were caused by gram-positive organisms[5,6]. This trend has also been reported in studies investigating spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and nosocomial infections in cirrhotic patients and may be attributed to widespread use of fluoroquinolone prophylaxis in this population[7,8]. Bouza et al[5] suggested however that etiology of the infection could be influenced by the onset of infection post TIPS insertion, which can be categorised as early-onset (within 120 d) or late-onset (over 120 d post insertion). In their review of 36 cases, they found that all Enterococcus spp exclusively occurred in early infections, which was not confirmed in our review, with no significant difference between the groups in number of Enterococcus spp cases isolated (P = 0.23; 95%CI: 0.08-1.77). There was also no significant difference in mortality between early and late infections (P = 0.76; 95%CI: 0.35-0.44). Our data also reflect an association between early-onset infections and gram-positive organisms.

Due to the wide variety of causative pathogens and overall rarity of this disease, it is highly unlikely that prospective data will guide management decisions of this clinical entity. As there is a variation in antibiotic choice and duration of treatment on review of the literature, the evidence base is too limited to support specific antibiotic recommendations. It may be reasonable that patients diagnosed with endotipsitis should be treated based on the principles of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) management, as in many ways the two disease entities are analogous. Both are endovascular infections involving difficult to remove prosthetic material that confer a high rate of treatment failure and relapse. We found antimicrobial management strategies that were overall quite divergent from the pathogen specific treatment guidelines for PVE. For example, staphylococcal PVE is generally treated with a cell wall active agent (e.g., oxacillin or vancomycin) plus rifampin and gentamicin[9]. Of the 9 cases of staphylococcal endotipsitis reported here, 7 treatment courses were previously published with none including gentamicin and only 2 including rifampin. It is impossible to know whether addition of these agents would have improved the poor response rate we saw in this subgroup (44%). Acknowledging the reluctance of using drugs with potential hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, in the face of treatment response rates below 50%, the potential benefits may outweigh the risks, when administering in a monitored setting.

S. aureus and Candida spp are both known to be able to resist the antimicrobial effects of antibiotics through the formation of biofilms[10]. This propensity underlies the rationale to remove medical devices such as central venous catheters when infected with these organisms, thus reducing the attributable mortality[11]. When comparing the treatment of monomicrobial infections in endotipsitis cases, there was a significantly lower response rate to antimicrobials alone in those with S. aureus or candidal infection compared to other pathogens. Therefore, when managing these patients, transplantation should be considered as a means of cure, as there is a significantly lower chance that they will respond with antibiotics and retention of the TIPS.

Of the 6 cases of fungal endotipsitis (all Candida spp), only 2 responded to antifungal treatment. Similarly, Candida spp are the most common cause of fungal infective endocarditis (IE), with these patients more likely to have prosthetic intravascular devices[12]. Baddley et al[12] found persistently positive blood cultures were associated with this group as well as a significantly higher rate of mortality when compared to non-fungal cases of IE[13]. With the accumulating evidence of dismal outcomes in patients with candidal endotipsitis, strong consideration for urgent transplantation needs to be contemplated in appropriate patients[14,15].

In patients who are ineligible for transplantation aggressive medical therapy and potentially chronic suppressive antibiotics should be considered acknowledging the prognosis is poor. In general, the role and timing of liver transplantation in the setting of endotipsitis is poorly understood. In our review we identified four patients who underwent transplantation. Mizrahi et al[1] did report clearance of blood cultures prior to transplant in their 2 cases[16,17]. Jawaid et al[15] described a case with repeat episodes of bacteraemia, 1 mo after TIPS insertion, with 9 different microorganisms isolated from blood cultures over the period of 11 mo. Willner et al[16] reported persistent polymicrobial bacteraemia 4 d after a TIPS revision, which resulted in a transplant 3 mo later (after 3 episodes of bacteraemia). It unclear whether the patients had negative blood cultures leading up to their transplant. In both cases, a biliary-venous fistula was not identified until after the assessment of the explant. Among patients with suspected endotipsitis and persistent or relapsing bacteremia, biliary-venous fistula should be considered and in this setting transplantation would be warranted to achieve cure.

Optimal treatment of endotipsitis remains elusive given the difficulty of studying a rare disease without a broadly accepted definition and caused by a variety of microbes. Our data suggests that infections caused by S. aureus and Candida spp is associated with particularly poor outcomes. Based on the treatment of PVE, addition of gentamicin and rifampin to cell wall active antimicrobials may improve outcomes of S. aureus endotipsitis cases. Transplantation should be strongly considered in the setting of relapsing disease and infections caused by difficult to eradicate pathogens. More data on the epidemiology and management outcomes of endotipsitis will be needed to determine the most appropriate prevention and treatment strategies.

“Endotipsitis” is a poorly understood complication of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures. Sustained or relapsing bacteraemia secondary to endovascular vegetative infection of the prosthesis, “endotipsitis”, is a rare but serious complication. The authors report a case with the longest latency from insertion to infection in the literature, supplemented by a review of the literature, in particular the management of this insidious and variable disease process.

Incidence and risk factors of endotipsitis are poorly understood due to difficulty in diagnosis and lack of a uniform disease definition. Furthermore, no unified agreement on the best management strategy for these cases to prevent relapses or mortality has been reached.

The authors’ data reflects an association between early-onset infections and gram-positive organisms. It also suggests that infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Candida spp are associated with particularly poor outcomes. The evidence base is too limited to support specific antibiotic recommendations, but it may be reasonable to treat based on the principles of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) management.

Transplantation should be strongly considered in those with infections associated with particularly poor outcomes, such as Candida spp. Based on the treatment of PVE, addition of gentamicin and rifampin to cell wall active antimicrobials may improve outcomes of S. aureus endotipsitis cases.

TIPS insertion is a minimally invasive procedure that is used for the decompression of elevated portal pressure. Although there is no universally accepted definition of “endotipsitis”, it is generally agreed that it can be defined as “definite” infection (continuous clinically significant bacteraemia with vegetative/thrombi inside TIPS) and “probable” infection (sustained bacteraemia with no other source of infection in a patient with TIPS).

The manuscript presents an interesting case of “endotipsitis” and reviews the literature on a rare disease. In this paper Navaratnam et al present a case of “endotipsitis” and performed a review of the existing literature on this field. They identified 22 papers reporting 54 patients with endotipsitis. The great majority had monomicrobial infections (gram positive agents were the majority). Infections with S. aureus and Candida spp were associated higher mortality. No homogeneous management was applied for the treatment of this condition and guidelines on antibiotics use are usually derivate from the treatment of endocarditis.

P- Reviewer: De Ponti F, Narciso-Schiavon JL, Procopet B

S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Mizrahi M, Adar T, Shouval D, Bloom AI, Shibolet O. Endotipsitis-persistent infection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: pathogenesis, clinical features and management. Liver Int. 2010;30:175-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kochar N, Tripathi D, Arestis NJ, Ireland H, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. Tipsitis: incidence and outcome-a single centre experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:729-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sanyal AJ, Reddy KR. Vegetative infection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:110-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fisher RA. On the interpretation of Chi-square from contingency tables and the calculation of P. J R Stat Soc. 1922;85:87-94. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1674] [Cited by in RCA: 1727] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bouza E, Muñoz P, Rodríguez C, Grill F, Rodríguez-Créixems M, Bañares R, Fernández J, García-Pagán JC. Endotipsitis: an emerging prosthetic-related infection in patients with portal hypertension. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;49:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Armstrong PK, MacLeod C. Infection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt devices: three cases and a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:407-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fernández J, Navasa M, Gómez J, Colmenero J, Vila J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2002;35:140-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 629] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gould FK, Denning DW, Elliott TS, Foweraker J, Perry JD, Prendergast BD, Sandoe JA, Spry MJ, Watkin RW. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of endocarditis in adults: a report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:269-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Harriott MM, Noverr MC. Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus form polymicrobial biofilms: effects on antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3914-3922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Steinbach WJ, Perfect JR, Cabell CH, Fowler VG, Corey GR, Li JS, Zaas AK, Benjamin DK. A meta-analysis of medical versus surgical therapy for Candida endocarditis. J Infect. 2005;51:230-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Falcone M, Barzaghi N, Carosi G, Grossi P, Minoli L, Ravasio V, Rizzi M, Suter F, Utili R, Viscoli C, Venditti M; Italian Study on Endocarditis. Candida infective endocarditis: report of 15 cases from a prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Baddley JW, Benjamin DK, Patel M, Miró J, Athan E, Barsic B, Bouza E, Clara L, Elliott T, Kanafani Z, Klein J, Lerakis S, Levine D, Spelman D, Rubinstein E, Tornos P, Morris AJ, Pappas P, Fowler VG, Chu VH, Cabell C; International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study Group (ICE-PCS). Candida infective endocarditis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:519-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mora-Duarte J, Betts R, Rotstein C, Colombo AL, Thompson-Moya L, Smietana J, Lupinacci R, Sable C, Kartsonis N, Perfect J. Comparison of caspofungin and amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2020-2029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1076] [Cited by in RCA: 939] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kullberg BJ, Sobel JD, Ruhnke M, Pappas PG, Viscoli C, Rex JH, Cleary JD, Rubinstein E, Church LW, Brown JM. Voriconazole versus a regimen of amphotericin B followed by fluconazole for candidaemia in non-neutropenic patients: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1435-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jawaid Q, Saeed ZA, Di Bisceglie AM, Brunt EM, Ramrakhiani S, Varma CR, Solomon H. Biliary-venous fistula complicating transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt presenting with recurrent bacteremia, jaundice, anemia and fever. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1604-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Willner IR, El-Sakr R, Werkman RF, Taylor WZ, Riely CA. A fistula from the portal vein to the bile duct: an unusual complication of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1952-1955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mizrahi M, Roemi L, Shouval D, Adar T, Korem M, Moses A, Bloom A, Shibolet O. Bacteremia and “Endotipsitis” following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. World J Hepatol. 2011;3:130-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | DeSimone JA, Beavis KG, Eschelman DJ, Henning KJ. Sustained bacteremia associated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:384-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Colston JM, Scarborough M, Collier J, Bowler IC. High-dose daptomycin monotherapy cures Staphylococcus epidermidis ‘endotipsitis’ after failure of conventional therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii: bcr2013009529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Brown RS, Brumage L, Yee HF, Lake JR, Roberts JP, Somberg KA. Enterococcal bacteremia after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS). Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:636-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Passeron A, Mihaïla-Amrouche L, Perreira Rocha E, Wyplosz B, Capron L. [Recurrent enterococcal bacteremia associated with a transjugular intrahepatic protosystemic shunt]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:1284-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zaman MM, Recco R, Tejwani U, Scuto TJ, Ahmed S, Hypolite A, Jayaraman G. Case of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium infection associated with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt that was treated with quinupristin/dalfopristin after bacteremia persisted with alatrofloxacin therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:954-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Eversman D, Chalasani N. A case of infective endotipsitis. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Medina-Gens L, López J, Manzanedo B, Pintado V. [Endotipsitis due to Gemella morbillorum]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2007;25:419-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aggarwal S, Park J. Endotipsitis: a diagnostic challenge. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Marques N, Sá R, Coelho F, da Cunha S, Meliço-Silvestre A. Spondylodiscitis associated with recurrent Serratia bacteremia due to a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS): a case report. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:525-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Barrio J, Castiella A, Von Wichman MA, Cosme A, López P, Arenas JI. [Spontaneous bacteremia due to Salmonella hadar in liver cirrhosis with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;22:79-81. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Brickey TW, Trotter JF, Johnson SP. Torulopsis glabrata fungemia from infected transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stent. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:751-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Darwin P, Mergner W, Thuluvath P. Torulopsis glabrata fungemia as a complication of a clotted transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:89-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Schiano TD, Atillasoy E, Fiel MI, Wolf DC, Jaffe D, Cooper JM, Jonas ME, Bodenheimer HC, Min AD. Fatal fungemia resulting from an infected transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stent. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:709-710. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Anstead GM, Martinez M, Graybill JR. Control of a Candida glabrata prosthetic endovascular infection with posaconazole. Med Mycol. 2006;44:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Suhocki PV, Smith AD, Tendler DA, Sexton DJ. Treatment of TIPS/biliary fistula-related endotipsitis with a covered stent. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:937-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |