Published online Oct 8, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i22.2411

Peer-review started: April 30, 2015

First decision: June 25, 2015

Revised: August 10, 2015

Accepted: September 10, 2015

Article in press: September 16, 2015

Published online: October 8, 2015

Processing time: 158 Days and 9.8 Hours

AIM: To review the post-operative morbidity and mortality of total esophagogastrectomy (TEG) with second barrier lymphadenectomy (D2) with interposition of a transverse colon and to determine the oncological outcomes of TEG D2 with interposition of a transverse colon.

METHODS: This study consisted of a retrospective review of patients with a cancer diagnosis who underwent TEG between 1997 and 2013. Demographic data, surgery protocols, complications according to Clavien-Dindo classifications, final pathological reports, oncological follow-ups and causes of death were recorded. We used the TNM 2010 and Japanese classifications for nodal dissection of gastric cancer. We used descriptive statistical analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS: The series consisted of 21 patients (80.9% men). The median age was 60 years. The 2 main surgical indications were extensive esophagogastric junction cancers (85.7%) and double cancers (14.2%). The mean total surgery time was 405 min (352-465 min). Interposition of a transverse colon through the posterior mediastinum was used for replacement in all cases. Splenectomy was required in 13 patients (61.9%), distal pancreatectomy was required in 2 patients (9.5%) and resection of the left adrenal gland was required in 1 patient (4.7%). No residual cancer surgery was achieved in 75.1% of patients. A total of 71.4% of patients had a postoperative complication. Respiratory complications were the most frequently observed complication. Postoperative mortality was 5.8%. Median follow-up was 13.4 mo. Surgery specific survival at 5 years of follow-up was 32.8%; for patients with curative surgery, it was 39.5% at 5 years.

CONCLUSION: TEG for cancer with interposition of a transverse colon is a very complex surgery, and it presents high post-operative morbidity and adequate oncological outcomes.

Core tip: Esophagogastric junction cancers are rare tumors that have increased in prevalence in recent decades due to lifestyle changes. Key results of this study are as follows: (1) We describe a treatment for patients with esophago-gastric junction cancer; (2) We show the surgical details in high quality artwork to better represent the surgery; and (3) We show the postoperative and oncological outcomes of this technique.

- Citation: Ceroni M, Norero E, Henríquez JP, Viñuela E, Briceño E, Martínez C, Aguayo G, Araos F, González P, Díaz A, Caracci M. Total esophagogastrectomy plus extended lymphadenectomy with transverse colon interposition: A treatment for extensive esophagogastric junction cancer. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(22): 2411-2417

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i22/2411.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i22.2411

The incidence of esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer has increased steadily in the West for the last 4 decades, with a currently reported prevalence of 5 cases per 100000 people. EGJ cancer corresponds to the increment of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and cardia, which are related to Barrett’s esophagus, obesity, pathological gastro-esophageal reflux and smoking[1-4].

Globally, these types of cancers are considered to have a poor prognosis, with a survival rate of 20% at 5 years follow-up in patients who underwent surgery[5]. Another study that included more patients was conducted by Rüdiger Siewert et al[6], and a 5-year survival of 32.5% was reported when surgery was performed.

The management of EGJ cancer is controversial. There are several surgical treatment alternatives that differ in morbidity, chance of no residual tumor (R0), and type of lymph node dissection, and there is no consensus on which method is considered to be the best alternative.

Total esophagogastrectomy (TEG) with the interposition of a transverse colon is recommended for patients with extensive EGJ cancers (cancer that has a significant invasion of the esophagus and stomach) or for patients with a concomitant esophageal and gastric cancer (also called double cancer).

TEG with second barrier lymph node dissection (D2) is an infrequently performed surgery because it has been associated with a high postoperative morbidity. Considering national series, only series of less than 20 patients with EGJ cancer have been published to date[7-9].

The main objectives of this study are: (1) to review the post-operative morbidity and mortality of TEG D2 with interposition of a transverse colon; and (2) to determine the oncological outcomes of TEG D2 with interposition of a transverse colon.

This study consisted of a retrospective review of patients with cancer who underwent TEG between 1997 and 2013. Demographic data, surgery details, postoperative complications, pathological reports of the surgical specimen and oncologic follow-up were recorded.

Information was obtained from medical records, surgery protocols, oncological controls and the national registry of civil information. We used the TNM 2010 and the Japanese classifications for nodal dissection of gastric cancer[10,11]. This study was approved by the ethics committee of our center.

Preoperative evaluation of patients included upper digestive endoscopy; computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis with use of intravenous contrast; spirometry; colonoscopy; arterial gasometry; serum albumin; general laboratory tests and specific evaluations for each patient’s comorbidities. Once the evaluations were complete, the patient was presented in a clinical-radiological meeting of the center, where the best treatment alternative was discussed.

Preoperative treatment of patients included motor and respiratory physiotherapy and colon preparation. A nutritionist assessed all patients. In the cases of patients who presented with significant dysphagia or did not improve their preoperative nutritional status, parenteral nutrition was recommended.

The patient is placed in a supine position over the operating table with the neck rotated to the right side. An upper midline laparotomy is performed, extending it by 2 cm below the umbilicus, and a left cervical approach is also performed.

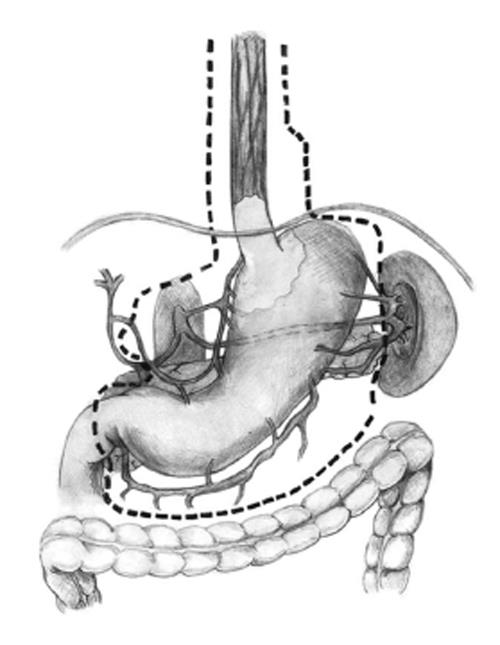

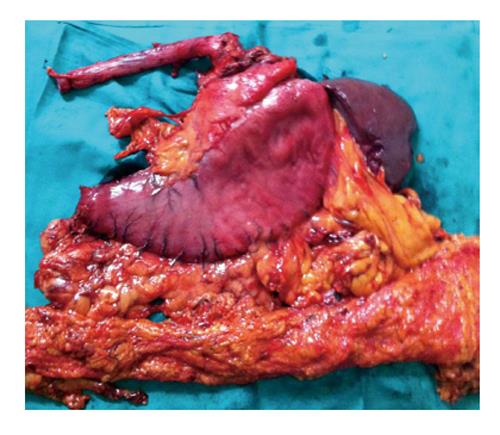

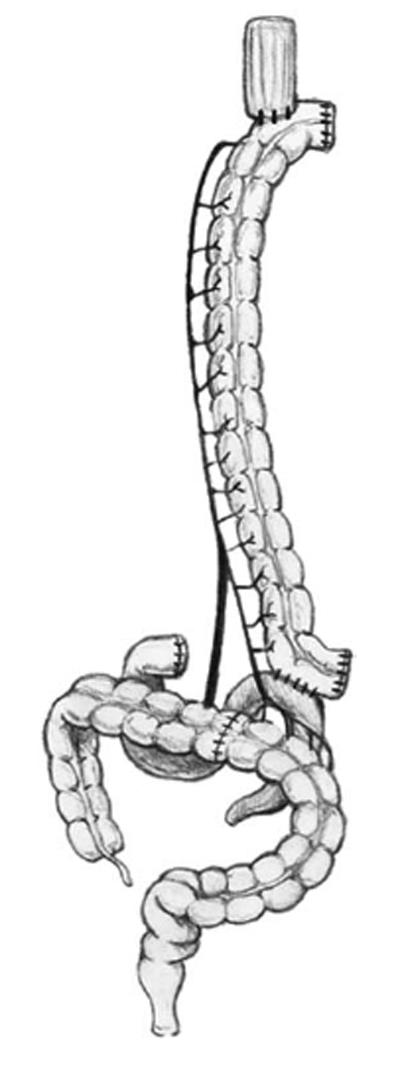

(1) Exploration of the abdominal cavity searching for the presence of metastasis; (2) Resection of the round ligament of the liver; (3) Dissection of the left triangular ligament and enlargement of the hiatus by a vertical incision on the diaphragm (Pinotti maneuver); (4) Determination of concomitant extension of EGJ cancer into the esophagus and stomach and, if it is significant, performance of the TEG; (5) Performance of an esophagectomy using a transhiatal plus left cervical approach. Dissection of the lower mediastinum and EGJ lymph nodes; (6) Sectioning of the cervical region of the esophagus and near total displacement of the mobilized esophagus into the abdominal cavity through the hiatus. A suture or nasogastric tube is used to guide the colon into the neck through the posterior mediastinum; (7) Performance of a total D2 gastrectomy with omentectomy and bursectomy (Figure 1); (8) Performance of a splenectomy in patients with macroscopic group 11 lymph node metastasis (LNM), or if spleen cancer invasion is observed; and (9) Placement of the surgical specimen on a secondary surgical table for dissection by the surgeon at the end of the surgery (Figure 2)[12].

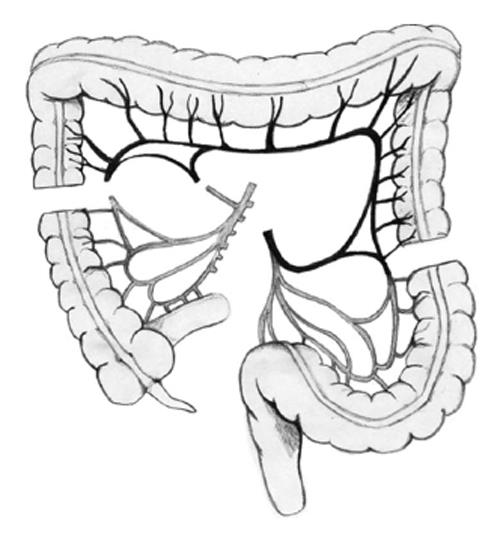

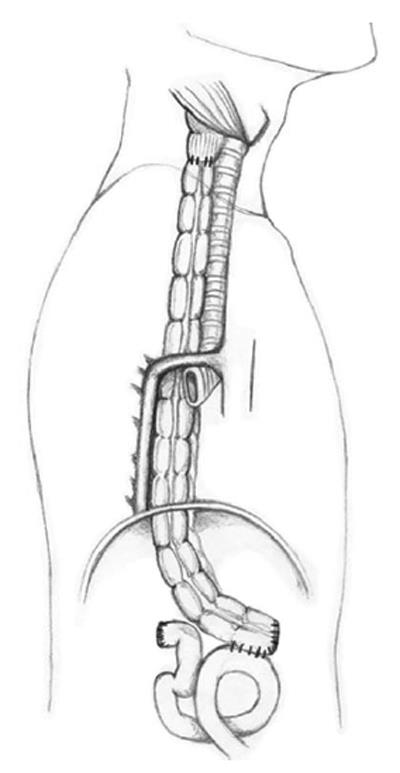

(1) Dissection of the colon from the cecum to the sigmoid; (2) Selective clamping of the middle and left colic arteries to determine the quality of transverse colon irrigation (colon coloration is observed and the pulse of the marginal artery is observed and manually estimated); (3) Sectioning of the middle colic artery at its origin, preserving Drummond’s vascular arcade (Figure 3); (4) Measurement of the transverse colon; i.e., distance from the patient’s neck to the root of the mesentery. This measure is applied on the surface of the colon following irrigation from the root of the mesentery to the proximal end; (5) Sectioning of the proximal transverse colon with a blue load of a linear cutting stapler (in the place previously measured; Figure 3); (6) Sectioning of the distal transverse colon where the left colic artery arrives with a blue load of a linear cutting stapler, preserving the continuity of the marginal artery (Figure 3); (7) Ascension of the isoperistaltic transverse colon through the posterior mediastinum to the neck (Figure 4); (8) Manual performance of a coloesophageal anastomosis, colojejunal anastomosis and colo-colonic anastomosis (Figure 5); (9) Performance of a Witzel type jejunostomy; (10) Installation of one drainage tube to each pleura; and (11) Installation of a Jackson-Pratt type drainage tube to the neck.

A statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0. A Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the years of post-operative survival. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

TEG and D2 lymph node dissection with transverse colonic interposition was performed between 1997 and 2013 in 21 patients who had extensive EGJ cancer or double cancer. There were 17 (80.9%) men and 4 women (19.1%), with a median age of 60 years (46.7 to 64.2 years). Twelve patients were classified according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA-1), 8 patients were classified as ASA-2 and 1 patient was classified as ASA-3. The pre-surgery median serum albumin value was 4 g/dL (3.5-4.2 g/dL).

The mean total surgery time was 405 min (352-465 min). Interposition of the transverse colon through the posterior mediastinum was used for replacement in all cases. Splenectomy was required in 13 patients (61.9%), distal pancreatectomy was required in 2 patients (9.5%) and resection of the left adrenal gland was required in 1 patient (4.7%).

The indications of the TEG D2 were: (1) extensive EGJ cancer in 18 patients (85.7%); and (2) two concomitant cancer (esophageal and gastric) in 3 patients (14.2%).

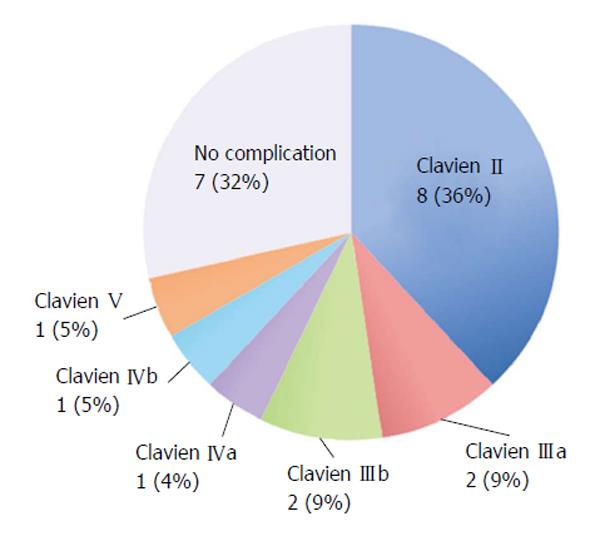

The median hospital stay was 17 d (7 to 26 d), and the median re-feeding time was 11.5 d (8 to 19 d). A total of 15 (71.4%) patients presented with the following complications (detailed according to the Clavien-Dindo classifications in Figure 6): 7 patients (33.3%) presented with a cervical esophagus-colonic anastomosis leak that was managed with medical treatment; 2 patients (9.5%) presented with a colo-colonic anastomosis leak, and both of these patients underwent reoperation. One of them received a new anastomosis and died afterwards, and the other patient underwent a colostomy with a mucous fistula; therefore, the intestinal transit was successfully reconstituted. One patient (4.7%) presented with a colo-duodenal anastomosis leak that was treated medically; 2 patients (9.5%) presented with obstruction of the jejunostomy. Of those patients, 1 patient needed to be reoperated due to a twist of the jejunostomy, and the second patient, who presented with only a partial obstruction, was resolved by removing the jejunostomy tube. The main medical complications were of the respiratory type, occurring in 9 patients (42.8%). The details of the complications are presented in Table 1.

| Surgical |

| Esophagocolonic anastomosis leak: 7 (33.3%) |

| Colocolonic anastomosis leak: 2 (9.5%) |

| Colojejunal leak: 1 (4.7%) |

| Jejunostomy obstruction: 2 (9.5%) |

| Intraabdominal collection: 4 (19%) |

| Infection of surgery wound: 4 (19%) |

| Medical |

| Respiratory: 9 (42.8%) |

| Sepsis by central venous catheter: 2 (9.5%) |

| Atrial fibrillation: 1 (4.7%) |

| Clostridium difficile diarrhea: 1 (4.7%) |

When observing patients with EGJ cancer, they all presented with pathological evidence of adenocarcinoma. Three patients presented with more than one tumor: 2 of these patients had concomitant esophageal squamous cancer and gastric adenocarcinoma, and the other patient had 3 tumors, including two gastric adenocarcinomas and one squamous esophageal cancer. The median tumor size was 8 cm (6.3 to 12 cm), and the median count of lymph nodes removed was 37 (27 to 49 lymph nodes).

R0 surgery was achieved in 16 patients (76.1%), 1 patient (4.7%) underwent R1 surgery (presenting with positive radial edges) and 4 patients (19%) underwent R2 surgery (3 of those patients presented with isolated peritoneal metastasis and 1 patient presented with incidental finding of pleural metastasis).

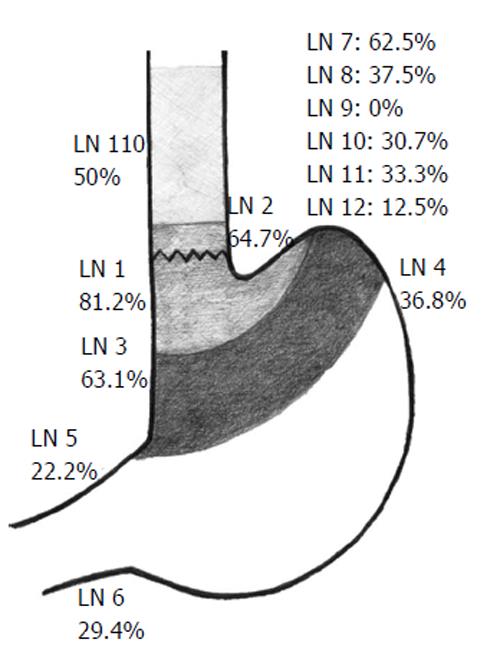

The distribution of LNM is shown in Figure 7. The lymph node groups most associated with metastasis were group 1 (81.2%); group 2 (64.7%); group 3 (63.1%); group 7 (62.5%) and group 110 (50%).

Three (14.2%) patients were staged as IIB, 1 (4.7%) was staged as IIIA, 1 (4.7%) was staged as IIIB, 12 (57.1%) were staged as IIIC and 4 (19%) were staged as IV.

To date, a total of 17 patients (80.9%) died: 11 died of cancer (64.7%), 1 died in the post-operative period (5.8%) and 5 died because of non-cancer related causes (29.4%).

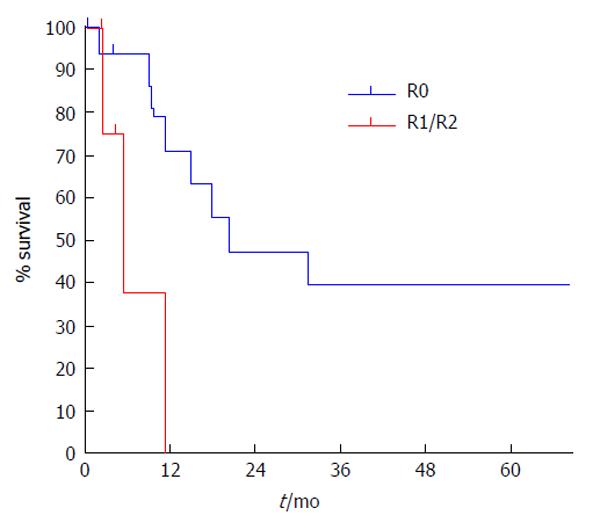

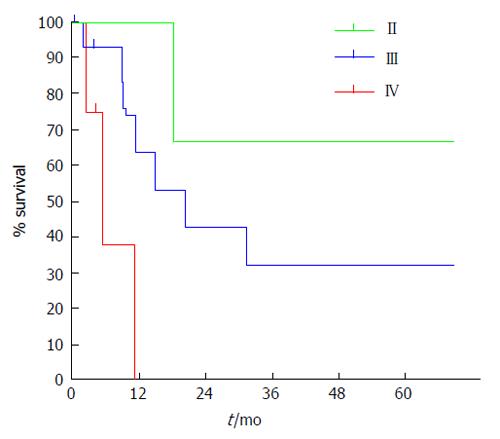

The estimated specific survival rate for patients at 5 years follow-up was 32.8% with a median of 18.1 mo. The estimated specific survival rate for patients with R0 surgery at 5 years follow-up was 39.6% with a median of 20.5 mo (Figures 8 and 9).

EGJ cancer is an epidemiologically relevant pathology. There has been a significant increase in its incidence in recent decades, and there will be a greater number of patients with this disease in the future[2-4,13].

The increasing incidence of EGJ cancer is related to changes in lifestyle in developed countries, such as changes in eating habits. In those countries, there are also higher prevalences of gastro-esophageal reflux, Barrett’s esophagus and obesity[14]. However, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms linking those changes to EGJ cancer are still not clear.

Whether EGJ cancer should be considered in the same group as esophageal and gastric cancer or if it corresponds to a different type of cancer because of its different oncological prognosis and lymph nodal spreading is controversial. Therefore, various surgical treatment alternatives have been described, such as total esophagectomy, partial esophago-gastrectomy (Ivor-Lewis and Merendino) and TEG. No consensus has been established when deciding which method is the most appropriate. In the last decade, this cancer was imprecisely classified in the 2006 TNM, and subsequently, it was grouped together with esophageal cancer in the 2010 TNM classifications[10]. This difficulty in grouping corresponds to the several different types of tumors than can compromise the EGJ, with some of the tumors behaving as an esophageal cancer and others having a gastric cancer behavior.

In 1996, Siewert et al[15,16] made a topographic classification, which allows planning and standardization of the surgical treatment and comparing outcomes. EGJ cancer type I is treated similarly to esophageal cancer, with esophagectomy plus proximal gastrectomy[17], and EGJ cancer type III is treated with a total gastrectomy[18]. EGJ type II tumors are usually treated with methods similar to those used for type III tumors because of the frequent involvement of the intra-abdominal lymph nodes, unless they present a greater esophageal involvement in the preoperative study, in which a proximal esophagogastrectomy plus abdominal and mediastinal lymphadenectomy is preferred. The type of approach and reconstruction in these cases can vary according to the center; some centers prefer a combined abdominal and thoracic approach, and other centers prefer exclusively a transhiatal approach. Regarding the type of reconstruction, it is possible to perform reconstruction with interposition of the stomach into the thorax (Ivor Lewis) or with interposition of a distal organ (colon or bowel).

One of the most difficult aspects to determine in patients with Siewert’s type II or type III large EGJ tumors, also called EGJ cancer type IV by Burmeister et al[8], is the length of the extension of the esophageal tumor involvement when performing preoperative studies. Therefore, in some cases, the choice of the treatment alternative for surgery is made during the intra-operative period. It has been established that in order for the treatment to meet oncological criteria, it has to ensure a macroscopic tumor-free margin of at least 5-10 cm in the esophagus[19-22]. At the other extreme, 2 cm is considered as a macroscopic tumor-free margin of poor prognosis or insufficient in a Japanese series. Therefore, we performed a total esophagectomy with total gastrectomy if an esophageal macroscopic tumor-free margin of less than 10 cm was determined while in surgery[19-22].

The aforementioned situation is why patients with EGJ cancer should be prepared for an eventual TEG and colon interposition plus an extended lymph node dissection (D2), due to the frequent lymph node metastasis of groups 1, 2, 3 and 7 of the Japanese classifications[6,7,23].

A second group of patients in whom the indication of TEG is clearer, are those who have a concomitant esophageal and gastric cancer (double cancer).

In this study, a splenectomy was performed only when evidence of invasion of the splenic hilum was found or in cases when significant LNM of groups 10 and 11 of the Japanese classifications were found. Resection of other organs such as the pancreas or adrenal gland is recommended only in cases with evidence of direct invasion by the tumor.

While reviewing this series, we observed a high morbidity (68%) and respiratory complications were the most frequently observed (40%), followed by leakage of the esophageal-colon anastomosis (30%); however, only 1 postoperative death (5%) was observed. These results were similar to results reported in other series of TEG and can even be compared to a series of patients who underwent proximal esophagogastrectomy[8], suggesting that multidisciplinary management is crucial for the management of postoperative complications.

Oncological results observed in this study were very satisfying when compared to large series, resulting in a 39.6% survival rate at 5 years follow-up and a median of 20.5 mo of survival when curative surgery was achieved. The surgical results obtained in this study showed that it is still controversial to perform this procedure with palliative intention; however, it showed better outcomes than other palliative procedures such as esophageal prosthesis, a gastrostomy or palliative chemotherapy. Similar to our series, Siewert’s study even had patients who underwent palliative TEG who were reported to have survival after 1 year of follow-up[6].

TEG D2 has a high postoperative morbidity rate, which suggests that it should be performed only in specialized centers that are dedicated to high complexity oncological surgeries.

Total esophagectomy associated with total gastrectomy for cancer is a highly complex surgery, associated high postoperative morbidity and infrequently indicated. The literature reported about 20% overall survival at 5 years.

Describe surgery in patients with cancers of the gastroesophageal junction, which is feasible, the main complication is respiratory cancer and has good oncological results.

The difference with other studies, is that described in detail the surgical steps, also includes high quality diagrams to understand step by step surgery.

This study provides interesting information to indicate total esophagogastrectomy, in selected patients, which is useful even in patients in advanced stages, with more than 12 mo survival.

TEG: Total esophagogastrectomy; EGJ: Esophagogastric junction.

This is a interesting article for surgeon. The authors’ work is very meaningful.

P- Reviewer: Shen G, Shiryajev YN S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Vial M, Grande L, Pera M. Epidemiology of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, gastric cardia, and upper gastric third. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;182:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, Fraumeni JF. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1991;265:1287-1289. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pera M, Cameron AJ, Trastek VF, Carpenter HA, Zinsmeister AR. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:510-513. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049-2053. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Whitson BA, Groth SS, Li Z, Kratzke RA, Maddaus MA. Survival of patients with distal esophageal and gastric cardia tumors: a population-based analysis of gastroesophageal junction carcinomas. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rüdiger Siewert J, Feith M, Werner M, Stein HJ. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: results of surgical therapy based on anatomical/topographic classification in 1,002 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232:353-361. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Butte JM, Waugh E, Parada H, De La Fuente H. Combined total gastrectomy, total esophagectomy, and D2 lymph node dissection with transverse colonic interposition for adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction. Surg Today. 2011;41:1319-1323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burmeister LR, Benavides C. Cáncer gastroesofágico. Revista colombiana de cirugía. 2000;15:238-242 Available from: http://bases.bireme.br/cgi-bin/wxislind.exe/iah/online/?IsisScript=iah/iah.xis&src=google&base=LILACS&lang=p&nextAction=lnk&exprSearch=327543&indexSearch=ID. |

| 9. | Abularach CR, Venturelli MF, Cerda CR, Urizar A, Lira E, Haito Y, Matus LC. Interposición de colon transverso Como alternativa de reconstrucción tras la esofagogastrectomía total. Rev Chil Cir. 2011;63:432-436. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW. Esophagus and esophagogastric junction. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer Verlag 2010; 103-111. |

| 11. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1897] [Article Influence: 135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ceroni VM, García CC, Vallejos HR, Zamarin J, Benavides C, Cid H, Rubilar P, Quijada MI, Solar F, Solar I. Valoración del análisis de la pieza operatoria en el cáncer gástrico por el cirujano. Rev Chil Cir. 2011;63:373-380. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pera M, Manterola C, Vidal O, Grande L. Epidemiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:151-159. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Concepts in the prevention of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and proximal stomach. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:334-351. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Siewert JR, Stein HJ, Sendler A, Fink U. Surgical resection for cancer of the cardia. Semin Surg Oncol. 1999;17:125-131. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1457-1459. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Bumm R, Feussner H, Bartels H, Stein H, Dittler HJ, Höfler H, Siewert JR. Radical transhiatal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy and endodissection for distal esophageal adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 1997;21:822-831. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Siewert JR, Fink U, Sendler A, Becker K, Böttcher K, Feldmann HJ, Höfler H, Mueller J, Molls M, Nekarda H. Gastric Cancer. Curr Probl Surg. 1997;34:835-939. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Barbour AP, Rizk NP, Gonen M, Tang L, Bains MS, Rusch VW, Coit DG, Brennan MF. Adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: influence of esophageal resection margin and operative approach on outcome. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1-8. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ito H, Clancy TE, Osteen RT, Swanson RS, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ, Ashley SW, Zinner MJ, Whang EE. Adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia: what is the optimal surgical approach? J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:880-886. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Mariette C, Castel B, Balon JM, Van Seuningen I, Triboulet JP. Extent of oesophageal resection for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:588-593. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Polkowski WP, van Lanschot JJ. Proximal margin length with transhiatal gastrectomy for Siewert type II and III adenocarcinomas of the oesophagogastric junction (Br J Surg 2013; 100: 1050-1054). Br J Surg. 2014;101:735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wayman J, Bennett MK, Raimes SA, Griffin SM. The pattern of recurrence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophago-gastric junction. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1223-1229. [PubMed] |