Published online Jul 18, 2015. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i14.1884

Peer-review started: March 30, 2015

First decision: April 27, 2015

Revised: June 16, 2015

Accepted: July 11, 2015

Article in press: July 14, 2015

Published online: July 18, 2015

Processing time: 116 Days and 19.5 Hours

AIM: To determine utility of transplant liver biopsy in evaluating efficacy of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) for hepatic venous obstruction (HVOO).

METHODS: Adult liver transplant patients treated with PTA for HVOO (2003-2013) at a single institution were reviewed for pre/post-PTA imaging findings, manometry (gradient with right atrium), presence of HVOO on pre-PTA and post-PTA early and late biopsy (EB and LB, < or > 60 d after PTA), and clinical outcome, defined as good (no clinical issues, non-HVOO-related death) or poor (surgical correction, recurrent HVOO, or HVOO-related death).

RESULTS: Fifteen patients meeting inclusion criteria underwent 21 PTA, 658 ± 1293 d after transplant. In procedures with pre-PTA biopsy (n = 19), no difference was seen between pre-PTA gradient in 13/19 procedures with HVOO on biopsy and 6/19 procedures without HVOO (8 ± 2.4 mmHg vs 6.8 ± 4.3 mmHg; P = 0.35). Post-PTA, 10/21 livers had EB (29 ± 21 d) and 9/21 livers had LB (153 ± 81 d). On clinical follow-up (392 ± 773 d), HVOO on LB resulted in poor outcomes and absence of HVOO on LB resulted good outcomes. Patients with HVOO on EB (3/7 good, 4/7 poor) and no HVOO on EB (2/3 good, 1/3 poor) had mixed outcomes.

CONCLUSION: Negative liver biopsy greater than 60 d after PTA accurately identifies patients with good clinical outcomes.

Core tip: Percutaneous angioplasty and/or stent placement is the first-line of treatment in patients with hepatic venous obstruction (HVOO) after liver transplantation. Recognizing recurrence of HVOO after percutaneous treatment solely based on clinical, laboratory or imaging findings is difficult, and there is not a clear consensus regarding which measure provides the best or “gold standard” assessment for response to treatment. We report the utility of biopsy in predicting outcomes of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) in patients with HVOO after liver transplantation. Specifically, we have found that patients without HVOO on a liver biopsy 60 d or more after PTA had no recurrence of HVOO on long-term follow-up.

- Citation: Sarwar A, Ahn E, Brennan I, Brook OR, Faintuch S, Malik R, Khwaja K, Ahmed M. Utility of liver biopsy in predicting clinical outcomes after percutaneous angioplasty for hepatic venous obstruction in liver transplant patients. World J Hepatol 2015; 7(14): 1884-1893

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v7/i14/1884.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i14.1884

Hepatic venous outflow obstruction (HVOO) is an uncommon complication after liver transplantation, occurring in 1.5%-2.5% of patients with orthotropic liver transplantation using the piggyback technique and up to 9.5% of patients with living donor liver transplantation[1-3]. HVOO can be treated either by percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) (i.e., using an inflatable balloon to treat a luminal stenosis; PTA), hepatic venous stenting, or when percutaneous revascularization is unsuccessful, by surgical revision[3-7]. Primary patency rates of PTA for HVOO at 1 year range from 51%-67% and recurrent HVOO after PTA occurs in 20%-50% of patients[3,4,6-9].

Response of HVOO to treatment may be determined based upon improvements in clinical symptoms, laboratory findings or imaging findings[10]. However, there is significant overlap of the clinical symptoms of HVOO and other causes for early and late allograft dysfunction such as rejection, drug toxicity or biliary complications[11]. Similarly, liver function tests do not always show significant change after successful PTA[8,12]. Finally, while an appropriate imaging response can be useful in determining effectiveness of PTA, imaging assessment can be subjective and may be operator dependent[6,13].

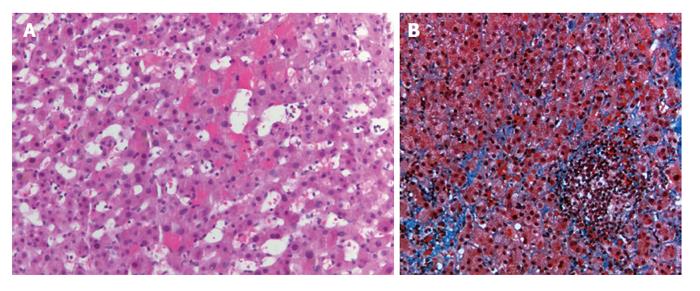

As such, liver biopsies are frequently performed to assess HVOO response to endovascular intervention and to distinguish persistent HVOO from other diseases in liver transplants, either at regular intervals or in response to change in the clinical or laboratory status[14]. Patients with HVOO usually have biopsy findings of zone 3 hepatocyte necrosis, sinusoidal congestion and hemorrhage in the space of Disse[15,16]. Correlation of histologic findings of HVOO with clinical findings such as pressure gradients between the hepatic vein and right atrium on manometry is not well studied. Furthermore, change in histologic findings following successful endovascular treatment is currently unknown. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to evaluate histologic findings at liver biopsy after PTA for HVOO in liver transplant patients and correlate these to treatment response and long-term outcome.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to initiation of the study. As this was a retrospective medical record review, the review board waived the need to obtain informed consent. We performed a retrospective, HIPAA-compliant electronic medical records review of all consecutive patients who underwent endovascular revascularization after liver transplantation. Between July 3, 2003 and September 12, 2013, 15 patients known or suspected to have HVOO after liver transplantation were referred for a total of 21 PTA procedures. Patients were suspected of having HVOO due to one or more of the following: core biopsy histology suggesting outflow obstruction [8/15 patients (53%), clinical symptoms (5/15 patients 33%), or imaging findings of outflow obstruction (2/15 patients)]. Biopsies prior to venograms were performed due to abnormal laboratory findings [7/10 (70%)] or clinical symptoms [3/10 (30%)]. Clinical symptoms suggestive of HVOO included lower extremity edema, ascites, and abdominal pain. Abnormal laboratory findings included elevated transaminases and elevated total bilirubin. Core biopsy findings consistent with HVOO were centrivenular or perivenular congestion, hemorrhage, and zone 3 hepatocyte atrophy (Figure 1)[15].

For patients in the study group, liver transplantation was performed between February 1998 and August 2013. Liver transplantation was performed due to hepatitis C virus induced cirrhosis [11/15 (73%)], primary sclerosing cholangitis [2/15 (13%)], alcoholic cirrhosis [1/15 (7%)] and autoimmune hepatitis induced cirrhosis [1/15 (7%)]. Two patients received living donor right liver grafts and the remaining patients received deceased donor transplants. Living donor transplant hepatic venous anastomoses were performed with either donor right hepatic vein (RHV) to recipient vena cava anastomosis or donor RHV to recipient RHV. Ten deceased donor transplant hepatic venous anastomoses were performed with piggyback technique, one was performed with side-to-side anastomosis, and two donor transplant hepatic venous anastomoses were unspecified (operative records not available in those two cases).

Informed consent regarding percutaneous hepatic venography, PTA and percutaneous or transjugular liver biopsy was obtained from the patient or the patient’s health care proxy during routine clinical care. Percutaneous venography and subsequent PTA was performed in the same session in all procedures. The procedure was primarily performed via right internal jugular (IJ) venous puncture [16/21 (76%) procedures]. In patients with unfavorable anatomy, other routes were used [right IJ and right common femoral vein 2/21 (10%), right common femoral vein only 2/21 (10%), left common femoral vein 1/21 (5%)].

After obtaining access to the infra-renal IVC and/or hepatic veins, pressure gradient between the hepatic vein/IVC and right atrium were determined using manometry. A decision to proceed to PTA was made by the operator based on one or more of the following criteria: the presence of pressure gradient > 2-3 mmHg (20), imaging findings of stenosis (> 50% narrowing in the hepatic vein outflow or IVC or both relative to pre- and post-vessel caliber), persistent clinical findings, or a combination of the above.

PTA was performed matching the balloon diameter to that of the vein on the hepatic side of the stenosis. In case of poor response to initial PTA, a larger diameter or higher pressure balloon was used. After balloon dilatation, venography and manometry were repeated to evaluate the effectiveness of PTA. No anticoagulation was prescribed after PTA. One patient, who underwent hepatic vein stenting, was placed on oral Coumadin for anticoagulation.

Liver core biopsies were performed after 13/21 (62%) PTA procedures. Post-PTA biopsies were performed once in 6 patients and multiple times in 9 patients for a total of 42 post-PTA biopsies. Of these biopsies, 35 (83%) were transhepatic and 7 (17%) were transjugular. Eighteen of 42 (43%) core biopsies were obtained using an 18 gauge needle, 3 (7%) were obtained using a 16 gauge needle, and the core biopsy needle caliber of the remaining procedures was not specified. The samples were sent to pathology placed in a formalin container. Early biopsy was defined as a biopsy performed within 2 mo (≤ 60 d) of PTA and late biopsy was defined as a biopsy performed greater than 2 mo (> 60 d) after PTA.

Medical records were accessed and available for all 15 patients. Medical records were reviewed for mortality, HVOO-related morbidity (e.g., lower extremity edema, recurrent ascites), repeat interventional procedures to relieve HVOO, persistent biopsy proven HVOO, surgical correction, re-transplantation, or HVOO-related death.

As part of our retrospective review, a single observer recorded the following data points: patient demographics, date and type of transplant, dates of all percutaneous revascularization procedures for the transplant hepatic veins, and dates and results of all transplant liver biopsies. For each percutaneous revascularization procedure, the name of the vessel, the luminal and vessel diameter at the point of maximal narrowing and the pre-PTA and post-PTA venous pressure gradients were recorded. For each patient, medical records were reviewed and clinical outcomes were recorded as persistent HVOO or no HVOO-related symptoms up to death, re-transplantation or loss to follow-up.

Technical success and patency rates were calculated. Technical success of PTA was defined as successful traversal of the stenosis with a catheter and completion of PTA. Clinical success was defined as resolution or improvement in presenting signs, symptoms or laboratory data or no further need for revascularization. Complications were defined by the Society of Interventional Radiology classification system[17]. Minor complications were defined as those requiring nominal or no additional treatment. Major complications were defined as those requiring significant additional treatment or hospitalization or those causing permanent sequelae up to death.

Primary patency was defined as the interval between initial PTA and first instance of a repeat hepatic venogram necessitated by adverse clinical status. Primary assisted patency was defined as patency after initial PTA until treatment with percutaneous intervention was abandoned.

“Good outcomes” were defined as resolution of clinical signs, symptoms, laboratory and/or imaging findings, resolution of venous congestion on biopsy findings and/or death due to non-HVOO related reasons. “Poor outcomes” were defined as unresolved clinical signs, symptoms, laboratory and/or imaging findings, re-transplantation, surgical correction and/or HVOO-related death.

Statistical analysis of pressure gradients before and after PTA was performed using a paired students t-test. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to determine primary patency and primary-assisted patency rates[3,4,6-9]. Patency rates were calculated for patients with sufficient clinical documentation during follow-up intervals. Patients were censored if they expired, underwent retransplantation for non-HVOO related causes or were lost to follow-up during the study interval. Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate correlation between biopsy findings and clinical outcomes. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Data processing and analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) and online statistical calculators (http://www.vassarstats.net).

Fifteen patients (10 males, 5 females, 54 ± 8 years) consecutive patients underwent 21 PTAs, 94 ± 184 wk (range 4-652 wk) after transplantation for treatment of HVOO.

All patients had successful traversal of the stenosis and PTA of the lesion resulting in a technical success rate of 100%. The gradient between stenosed vein and the right atrium was 7.5 ± 4 mmHg prior to PTA and 3.8 ± 3 mmHg after PTA (P = 0.001). The luminal diameter as a percentage of vessel diameters at the point of maximal narrowing was 50% ± 19% prior to PTA and 58% ± 22% after PTA (P = 0.21). PTA was performed once in 10 (66%) patients, twice in 4 (27%) patients and thrice in 1 (7%) patient. Primary patency was 79% at 30 d, 79% at 3 mo, 63% at 6 mo, 63% at 1 year and 52% at 3 years. Primary-assisted patency was 80% at 30 d and 79% at 3 mo, 6 mo, 1 year and 3 years. There were no minor or major complications.

Liver biopsies were performed prior to PTA in 19/21 (90%) procedures (Table 1). In patients with pre-PTA biopsy findings consistent with HVOO [13/19 (68%)], the maximum gradient ranged from 2-17 mmHg (8 ± 2.4 mmHg). In patients with no evidence of HVOO on pre-PTA biopsy [6/19 (32%)], the maximum gradient ranged from 5-11 mmHg (6.8 ± 4.3 mmHg). There was no significant difference in the pre-PTA pressure gradient between patients with evidence of HVOO on pre-PTA biopsy vs patients without evidence of HVOO on pre-PTA biopsy (P = 0.35).

| Patient No. | Procedure No. | Gradient (mmHg) | Biopsy findings indicating HVOO | Clinical outcome | |||

| Pre | Post | Pre- | < 60 d | > 60 d | |||

| 1 | 1 | 8 | NA | + | + | - | Good |

| 2 | 1 | 7 | NA | - | - | - | Good |

| 3 | 1 | 8 | 4 | + | + | - | Good |

| 4 | 1 | 5 | 8 | - | + | - | Good |

| 5 | 1 | 9 | 9 | NA | NA | - | Good |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | Good |

| 2 | 5 | 4 | - | NA | NA | Poor | |

| 7 | 1 | 15 | 17 | + | + | NA | Poor |

| 2 | 17 | 12 | + | NA | NA | Poor | |

| 8 | 1 | 7 | 2 | + | NA | NA | Poor |

| 9 | 1 | NA | NA | + | NA | + | Poor |

| 2 | 6 | 1 | + | NA | NA | Good | |

| 10 | 1 | 5 | NA | - | NA | NA | Good |

| 11 | 1 | 9 | 2 | + | - | + | Poor |

| 2 | 8 | 1 | - | NA | - | Good | |

| 12 | 1 | 2 | 2 | + | NA | NA | Good |

| 13 | 1 | 4 | NA | + | - | - | Good |

| 14 | 1 | 8 | 6 | + | + | NA | Poor |

| 2 | 5 | 4 | + | + | NA | Poor | |

| 3 | 11 | 5 | + | NA | NA | Poor | |

| 15 | 1 | 11 | 8 | - | + | NA | Poor |

In the 13 patients with pre-PTA biopsy showing hepatic venous congestion, 9/13 (70%) had clinical findings of venous stenosis (ascites, lower extremity edema, hepatomegaly, etc.) but only 4/13 (30%) had imaging findings of venous stenosis (on computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound). In the 6 patients with pre-PTA biopsy showing no hepatic venous congestion 5/6 (83%) had clinical findings of venous stenosis and only 2/6 (33%) had imaging findings of venous stenosis.

Post-PTA liver core biopsies were performed after 13/21 (61%) PTA procedures. Early biopsy was performed after 10/21 (48%) PTA (mean 29 ± 21 d, range 2-48 d); late biopsy was performed after 9/21 (43%) PTA (mean 153 ± 81 d, range 62-304 d) and 8/21 (38%) patients had no biopsy after PTA. Of patients with late biopsy, 6/9 (67%) had both early and late post-PTA biopsy, 3/9 (33%) patients had only late biopsy after PTA.

Patients with evidence of HVOO on early biopsy (n = 7) included 3/7 patients (43%) with no HVOO-related complications on follow-up (205-3096 d) and 4/7 patients (57%) with HVOO related complications requiring repeat PTA or surgical revascularization (1-47 d). Patients without evidence of HVOO on early biopsy (n = 3) included 2/3 patients (67%) with no HVOO related complications on follow-up (62-964 d) and 1/3 patients (23%) requiring repeat PTA (at 66 d).

Two patients with evidence of HVOO on late biopsy [2/9 (22%)] underwent additional revascularization. Patients without evidence of HVOO on late biopsy [7/9 (78%)] did not need revascularization [4/7 (57%)] with no clinical issues and 3/7 (43%) with non-HVOO related death in 205-964 d.

Patients with both early and late biopsy (n = 6) showed late biopsy findings to be more predictive of clinical outcomes (Table 2).

| Early biopsy findings | Late biopsy findings | Clinical outcome (days post-PTA) |

| HVOO (3 patients ) | No HVOO (3/3) | Non-HVOO related death (205 d) |

| Non-HVOO related death (242 d) | ||

| Doing well (3096 d) | ||

| No HVOO (3 patients ) | No HVOO (2/3) | Doing well (62, 964 d) |

| HVOO (1/3) | Needed repeat PTA (66 d) |

In patients with no biopsy after PTA (n = 8), 2 (25%) patients died of non-HVOO related causes (12 and 86 d post-PTA), 4 (50%) needed revascularization (8, 22, 43, 138 d post-PTA) and 2 (25%) are doing well (215 and 223 d post-PTA).

The correlation of histologic findings on early vs late biopsy with clinical outcomes is outlined in Table 2.

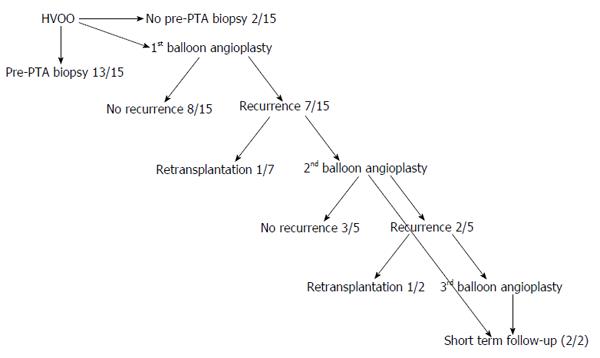

Clinical follow-up was available in all patients (mean: 56 ± 110 wk; Figure 2). Eight/15 (53%) patients had no recurrence of HVOO after a single PTA. Of the 7/15 (47%) patients with recurrence, 5 (71%) underwent repeat PTA, 1 (14%) underwent surgical revascularization and 1 (14%) needs further percutaneous treatment. Of the 5 patients undergoing repeat PTA 3/5 patients (60%) had no recurrence, 1/5 patients (20%) with recurrence required repeat PTA and 1/5 patients (20%) with recurrence resulting in re-transplantation (Table 1).

Importantly, of the 5 patients with clinical symptoms of HVOO without histological evidence of HVOO on pre-PTA biopsy, 60% (3/5) had a good outcome with resolution of clinical symptoms. Separately, in the 4/13 (30%) patients with histological evidence of HVOO without clinical symptoms of HVOO, 100% (4/4) had resolution of venous congestion on post-PTA biopsy.

Five out of 15 patients (33%) died of non-HVOO related causes (mean: 43 ± 54 wk, median 29 wk). Causes of death included cholestatic hepatitis, methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and sepsis, recurrent hepatitis C virus infection in the transplant liver and disseminated intravascular coagulation in 2 patients. In the remaining 10 patients, 6 (60%) are alive with no signs or symptoms of HVOO (mean follow-up 142 ± 181 wk, median 40 wk). In the remaining 4 patients, 2 (50%) underwent surgical correction for HVOO and 2 (50%) still have signs and symptoms of HVOO (3 and 8 d post-PTA).

Overall, histological findings on biopsies < 60 d did not correlate with clinical outcomes (P = 0.99) whereas histological findings on biopsies > 60 d correlated with clinical outcomes (P = 0.02).

Percutaneous angioplasty and/or stent placement is the first-line of treatment in patients with HVOO after liver transplantation. Recognizing recurrence of HVOO after percutaneous treatment solely based on clinical, laboratory or imaging findings is difficult, and there is not a clear consensus regarding which measure provides the best or “gold standard” assessment for response to treatment. While liver biopsy is often utilized to determine response to therapy and need for repeated treatments, pathologic results after intervention have not been correlated to clinical symptoms nor long-term clinical outcomes.

Here, in a retrospective review of this cohort at our institution, we report the utility of biopsy in predicting outcomes of PTA in these patients with HVOO after liver transplantation. Specifically, we have found that patients without HVOO on a liver biopsy 60 d or more after PTA had no recurrence of HVOO on long term follow-up. Conversely patients with HVOO on a liver biopsy performed more than 60 d after PTA had recurrent stenosis or other adverse outcomes. On the other hand, liver biopsy findings of HVOO on early biopsy (less than 60 d after PTA) did not correlate with treatment durability or long term outcomes. This “latency” period of 60 d between percutaneous treatment of HVOO and resolution of histological changes may represent the time needed for the liver to recover following successful treatment of HVOO. In clinical terms, a patient with HVOO on biopsy less than 60 d after PTA may not need repeat PTA, if there are no associated clinical symptoms (e.g., worsening ascites or lower extremity edema). On the other hand, patients with HVOO on biopsy more than 60 d after PTA represent an at-risk population and should undergo attempts at percutaneous or surgical revascularization.

In a recent study, Lorenz et al[9] reported the follow-up interval from PTA to the first biopsy demonstrating absence of HVOO. They found in 25 patients with primary inferior vena cava stenosis following liver transplantation, the interval from treatment to biopsy findings without evidence of HVOO was 37-4136 d. To our knowledge, no study has systematically investigated the ability of post-transplant liver biopsy to predict long-term response to percutaneous revascularization. However, features of HVOO on histology are known to overlap with features of other hepatic diseases such as chronic biliary disease or drug-induced reactions[15]. Therefore, the pathologist often recommends clinical correlation of histological findings suggestive of HVOO. While this may represent a limitation in our study, we used identical histological findings to categorize biopsy findings as HVOO in the two cohorts (biopsy less than and greater than 60 d after PTA) and found the latter to be more predictive of long-term outcomes.

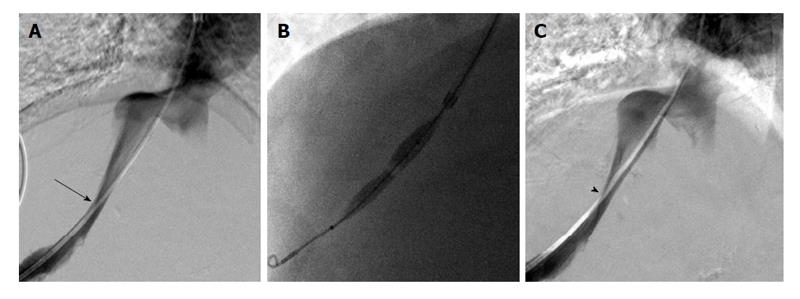

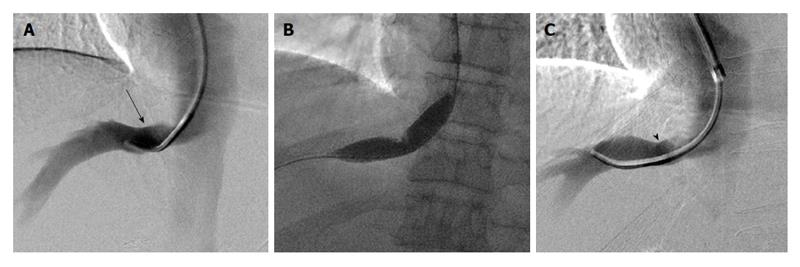

Additionally, we found intra-procedural parameters such as pressure gradients or luminal diameter to be poor surrogate markers of existing histologic HVOO and poor predictors of histologic response to therapy (Figures 3 and 4). In our study, four patients with HVOO on pre-PTA biopsy had a gradient less than 6 and 1 patient had a gradient less than 3. Specifically, there was no significant difference in pre-PTA pressure gradients between patients with or without evidence of HVOO on a pre-PTA biopsy. Similarly, improvement in pressure gradients to < 3 mmHg or persistent pressure gradients > 3 mmHg were not always associated with good or poor clinical response, respectively (Table 1, e.g., patients 3, 4, 5, 8). While gradients (rather than degree of stenosis on venography) have been the primary intra-procedural measure in all of the available studies on HVOO, there is currently no consensus on what constitutes an abnormal gradient between the hepatic veins and the right atrium. Early reports of PTA for HVOO recommended using a gradient of 10 mmHg[18,19] however, a surgical evaluation of normal hepatic vein to right atrium gradient during liver transplantation found the mean gradient to be less than 3 mmHg[20]. Multiple reports in the literature corroborate our findings of patients where an elevated post-PTA gradient (> 3 mmHg) can still have good clinical outcomes[3,4,6-8,21]. These findings suggest that a combination of clinical symptoms and biopsy findings are more accurate than any gradient threshold in diagnosing HVOO and a good clinical outcome may be obtained despite a post-PTA gradient > 3 mmHg.

Similarly, we found that 70% of patients with histological evidence of HVOO also have clinical symptoms but more importantly, even the 30% of these patients who do not have clinical symptoms show resolution of their histological findings after PTA. We also found that 83% of patients can have clinical symptoms of HVOO without histological evidence of HVOO. These findings support the combined used of clinical symptoms and pre-PTA biopsy findings in diagnosing HVOO and pursuing interventional treatment.

Finally, we report primary patency rates of 53% at 3 years and primary assisted patency rates of 79% at 3 years after only PTA for HVOO. This is similar to post-PTA patency rates reported in the literature using Kaplan-Meier analysis (Table 3). Some authors advocate the use of primary stenting for HVOO when it occurs early in the post-transplant period or when dealing with primarily IVC stenosis[3,9]. The patency rates for these studies were similar to our results, however, the hepatic veins are technically challenging for stent deployment and stent migration is a rare but severe complication[3,8]. Therefore, we agree with the use of PTA as a primary treatment for HVOO and reserving use of hepatic venous stenting for patients refractory to multiple PTA sessions, as previously proposed[8,22].

| Ref. | Transplant | Procedure | n | Follow-up | Primary patency rates | Primary assisted patency rates | Outcomes | Complications | ||||||||||||||||

| type | (converted to weeks) | 1 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 36 mo | 60 mo | 84 mo | 120 mo | 1 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 36 mo | 60 mo | 84 mo | 120 mo | |||||

| Kubo et al[4] | LDLT | 19 PTA, 1 PTA + stent | 20 | 20-334 wk (med: 129 wk) | 80 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 60 | NA | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | NA | NA | 9/20 recurrence, 0% retransplanted, 0% HVOO death | n = 1, transient hypotension | ||||||

| Lorenz et al[7] | OLT 15 LDLT 1 | 12 PTA, 2 PTA + stent, 3 only stent | 16 | 45-244 wk (mean: 161 wk) | 100 | 75 | 67 | 67 | 60 | NA | NA | NA | 93 | 91 | 90 | 89 | 88 | 83 | NA | NA | NA | 3/12 recurrence, 3/12 retransplanted, 3/12 non-HVOO deaths, 1/12 HVOO death | n = 1, transient hypoxia | |

| Ko et al[3] | LDLT | 108 only stent | 108 | 52-360 wk (mean: 39 mo) | 82 | 75 | 72 | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 22/108 recurrence, 2/108 retransplanted, 3 HVOO deaths | 4.60%, stent migration, stent malposition | |||||

| Ikeda et al[6] | LDLT | 9 PTA, 2 PTA + stent | 11 | 20-292 wk (med: 60 wk) | 78 | 78 | 67 | 67 | 56 | 56 | NA | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | NA | NA | 6/10 recurrence, 1/10 retransplanted, 2/10 death, 2/2 hepatic | n = 1, abdominal pain | ||||

| Yabuta et al[8] | LDLT | 41 PTA, 7 PTA + stent | 48 | 4-728 wk (med: 206 wk) | 64 | 57 | 57 | 52 | 98 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 20/48 recurrence, 2/48 retransplanted, 0/48 HVOO-related deaths | n = 1, stent migration | ||||||||||

| Lorenz et al[9] | OLT 23 LDLT 2 | 14 PTA, 4 PTA + stent, 10 only stent | 25 | 1-603 wk (mean: 192 wk) | 57 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | NA | 57 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | NA | 6/14 recurrence, 1/14 retransplanted, 3/14 died of primary graft failure | n = 1, fractured stent | ||||||

There are some limitations to our study. This includes a small sample size and retrospective nature of the study as well as the absence of a control group. However, given the low frequency of HVOO in liver transplant patients as well as the consequences of untreated HVOO, it is difficult to perform a prospective study or include a control group. Existing literature faces similar issues, as available studies to date include a similar number of patients and study design (2-109 patients)[3-9,13,18,19,21,22]. Secondly, a number of patients (4/15) did not undergo biopsy after PTA, however even within this group 2/4 patients had good clinical outcomes. A post-PTA biopsy may have helped distinguish these two patients with good outcomes from the six patients with poor outcomes. Therefore, biopsy has a role in stratifying patients with HVOO. Additionally, a small number of patients underwent revascularization based solely on clinical symptoms. We also acknowledge that the timeframe of histologic response after intervention for HVOO is variable, poorly characterized in the literature and likely not known. Further studies to correlate histologic changes to our 60 d timeframe are required, though this may be difficult to achieve given the small patient numbers available. Future studies can, however, help delineate if a post-PTA biopsy adds prognostic value above and beyond clinical or laboratory findings in determining recurrence of HVOO.

In conclusion, our study suggests that liver biopsy performed more than 60 d after treatment may be used to predict long-term clinical outcomes after primary PTA for relieving HVOO after liver transplantation.

Hepatic venous outflow obstruction (HVOO) is an uncommon complication after liver transplantation, occurring in 1.5%-2.5% of patients with orthotropic liver transplantation using the piggyback technique and up to 9.5% of patients with living donor liver transplantation. HVOO can be treated either by percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) (i.e., using an inflatable balloon to treat a luminal stenosis; PTA), hepatic venous stenting, or when percutaneous revascularization is unsuccessful, by surgical revision. As such, liver biopsies are frequently performed to assess HVOO response to endovascular intervention and to distinguish persistent HVOO from other diseases in liver transplants. Correlation of histologic findings of HVOO with clinical findings such as pressure gradients between the hepatic vein and right atrium on manometry is not well studied. Furthermore, change in histologic findings following successful endovascular treatment is currently unknown. Therefore, the purpose of the authors’ study was to evaluate histologic findings at liver biopsy after PTA for HVOO in liver transplant patients and correlate these to treatment response and long-term outcome.

The use of an appropriately timed biopsy to determine response to treatment after angioplasty of hepatic veins will improve patient outcomes and reduce uncertainity in treating these patients.

Although the techniques used to treat and assess these patients are well known. The precise correlation of histological findings with clinical findings, liver function tests and imaging findings as well as the effect of treatment on histological findings is not well known. This study shows the accuracy of post-angioplasty biopsy in determining prognosis.

These findings suggest that in patients who do not immediately respond to balloon angioplasty with improvement in clinical symptoms should undergo biopsy to determine histological response. However, the biopsy should be performed up to 60 d after endovascular treatment.

This is an interesting paper that assesses the utility of liver histopathology to predict the outcome of PTA after HVOO in transplant patients.

P- Reviewer: Baba H, Debbaut C, Quintero J S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Navarro F, Le Moine MC, Fabre JM, Belghiti J, Cherqui D, Adam R, Pruvot FR, Letoublon C, Domergue J. Specific vascular complications of orthotopic liver transplantation with preservation of the retrohepatic vena cava: review of 1361 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:646-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parrilla P, Sánchez-Bueno F, Figueras J, Jaurrieta E, Mir J, Margarit C, Lázaro J, Herrera L, Gómez-Fleitas M, Varo E. Analysis of the complications of the piggy-back technique in 1,112 liver transplants. Transplantation. 1999;67:1214-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ko GY, Sung KB, Yoon HK, Kim KR, Kim JH, Gwon DI, Lee SG. Early posttransplant hepatic venous outflow obstruction: Long-term efficacy of primary stent placement. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1505-1511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kubo T, Shibata T, Itoh K, Maetani Y, Isoda H, Hiraoka M, Egawa H, Tanaka K, Togashi K. Outcome of percutaneous transhepatic venoplasty for hepatic venous outflow obstruction after living donor liver transplantation. Radiology. 2006;239:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang SL, Sze DY, Busque S, Razavi MK, Kee ST, Frisoli JK, Dake MD. Treatment of hepatic venous outflow obstruction after piggyback liver transplantation. Radiology. 2005;236:352-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ikeda O, Tamura Y, Nakasone Y, Yamashita Y, Okajima H, Asonuma K, Inomata Y. Percutaneous transluminal venoplasty after venous pressure measurement in patients with hepatic venous outflow obstruction after living donor liver transplantation. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:520-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lorenz JM, Van Ha T, Funaki B, Millis M, Leef JA, Bennett A, Rosenblum J. Percutaneous treatment of venous outflow obstruction in pediatric liver transplants. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1753-1761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yabuta M, Shibata T, Shibata T, Shinozuka K, Isoda H, Okamoto S, Uemoto S, Togashi K. Long-term outcome of percutaneous interventions for hepatic venous outflow obstruction after pediatric living donor liver transplantation: experience from a single institute. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:1673-1681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lorenz JM, van Beek D, Funaki B, Van Ha TG, Zangan S, Navuluri R, Leef JA. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous venoplasty and Gianturco stent placement to treat obstruction of the inferior vena cava complicating liver transplantation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:114-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Darcy MD. Management of venous outflow complications after liver transplantation. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;10:240-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Curry MP. Systematic investigation of elevated transaminases during the third posttransplant month. Liver Transpl. 2013;19 Suppl 2:S17-S22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Deschenes M. Early allograft dysfunction: causes, recognition, and management. Liver Transpl. 2013;19 Suppl 2:S6-S8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Carnevale FC, Machado AT, Moreira AM, De Gregorio MA, Suzuki L, Tannuri U, Gibelli N, Maksoud JG, Cerri GG. Midterm and long-term results of percutaneous endovascular treatment of venous outflow obstruction after pediatric liver transplantation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1439-1448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Berenguer M, Rayón JM, Prieto M, Aguilera V, Nicolás D, Ortiz V, Carrasco D, López-Andujar R, Mir J, Berenguer J. Are posttransplantation protocol liver biopsies useful in the long term? Liver Transpl. 2001;7:790-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kakar S, Batts KP, Poterucha JJ, Burgart LJ. Histologic changes mimicking biliary disease in liver biopsies with venous outflow impairment. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:874-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dhillon AP, Burroughs AK, Hudson M, Shah N, Rolles K, Scheuer PJ. Hepatic venular stenosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;19:106-111. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Omary RA, Bettmann MA, Cardella JF, Bakal CW, Schwartzberg MS, Sacks D, Rholl KS, Meranze SG, Lewis CA. Quality improvement guidelines for the reporting and archiving of interventional radiology procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:S293-S295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Borsa JJ, Daly CP, Fontaine AB, Patel NH, Althaus SJ, Hoffer EK, Winter TC, Nghiem HV, McVicar JP. Treatment of inferior vena cava anastomotic stenoses with the Wallstent endoprosthesis after orthotopic liver transplantation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Raby N, Karani J, Thomas S, O’Grady J, Williams R. Stenoses of vascular anastomoses after hepatic transplantation: treatment with balloon angioplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ducerf C, Rode A, Adham M, De la Roche E, Bizollon T, Baulieux J, Pouyet M. Hepatic outflow study after piggyback liver transplantation. Surgery. 1996;120:484-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Simó G, Echenagusia A, Camúñez F, Quevedo P, Calleja IJ, Ferreiroa JP, Bañares R. Stenosis of the inferior vena cava after liver transplantation: treatment with Gianturco expandable metallic stents. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1995;18:212-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Umehara M, Narumi S, Sugai M, Toyoki Y, Ishido K, Kudo D, Kimura N, Kobayashi T, Hakamada K. Hepatic venous outflow obstruction in living donor liver transplantation: balloon angioplasty or stent placement? Transplant Proc. 2012;44:769-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |