Published online Jun 27, 2014. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i6.448

Revised: May 7, 2014

Accepted: May 16, 2014

Published online: June 27, 2014

Processing time: 135 Days and 8.1 Hours

The use of triple therapy for hepatitis C not only increases the rate of sustained virological responses compared with the use of only interferon and ribavirin (RBV) but also leads to an increased number of side effects. The subject of this study was a 53-year-old male who was cirrhotic with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 A and was a previous null non-responder. We initially attempted retreatment with boceprevir (BOC), Peg-interferon and RBV, and a decrease in viral load was observed in the 8th week. In week 12, he presented with disorientation, flapping, fever, tachypnea, arterial hypotension and tachycardia. He also exhibited leucopenia with neutropenia. Cefepime and filgrastim were initiated, and treatment for hepatitis C was suspended. A myelogram revealed hypoplasia, cytotoxicity and maturational retardation. After 48 h, he developed bilateral inguinal erythema that evolved throughout the perineal area to the root of the thighs, with exulcerations and an outflow of seropurulent secretions. Because we hypothesized that he was suffering from Fournier’s Syndrome, treatment was replaced with the antibiotics imipenem, linezolid and clindamycin. After this new treatment paradigm was initiated, his lesions regressed without requiring surgical debridement. Triple therapy requires knowledge regarding the management of adverse effects and drug interactions; it also requires an understanding of the importance of respecting the guidelines for the withdrawal of treatment. In this case report, we observed an adverse event that had not been previously reported in the literature with the use of BOC.

Core tip: Triple therapy is a recently developed strategy for the treatment of hepatitis C that requires extensive knowledge of adverse effects and drug interactions. It also requires an appreciation of the importance of respecting the guidelines for treatment withdrawal. The case report presented here describes a serious adverse event associated with this new therapy that has not previously been reported in the literature. This finding emphasizes the importance of adequately managing patients according to international clinical protocols, and our study allows for an exchange of experience among experts in the conduct of real-life cases.

- Citation: Oliveira KCL, Cardoso EOB, de Souza SCP, Machado FS, Zangirolami CEA, Moreira A, Silva GF, de Oliveira CV. Grade 4 febrile neutropenia and Fournier’s Syndrome associated with triple therapy for hepatitis C virus: A case report. World J Hepatol 2014; 6(6): 448-452

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v6/i6/448.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i6.448

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the principle cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis of the liver and hepatocarcinoma (CHC) throughout the world[1-4]. It is estimated that 120 to 200 million individuals are chronically infected with HCV worldwide, with chronic infections by the HCV genotype 1 being the most prevalent globally (40% to 80%)[1]. Although the incidence of acute hepatitis C has diminished significantly since screening for HCV in the donors of blood and its derivatives began in 1990, the number of patients who present with decompensated cirrhosis and CHC is expected to increase, reaching a peak in approximately 2020[1].

Fifty to 80% of individuals with an acute HCV infection will develop the chronic form of this infection. Of the infected individuals, 2% to 20% will develop cirrhosis within the first 20 years, and most evidence suggests that the disease progression may then increase in a nonlinear fashion. From the point at which cirrhosis is established, the rate of CHC development ranges from 1% to 6% per year. Numerous factors have been associated with rapid progression to cirrhosis, such as a greater age at the time of infection, being male, alcohol consumption, co-infections with the human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis B virus, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and tobacco smoking[1].

Over the past 10 years, standard therapy for chronic hepatitis C has consisted of a combination of Peg-interferon alpha and Ribavirin (RBV). This treatment results in a sustained virological response (SVR) in 40% to 50% of HCV genotype 1 patients and in approximately 80% of patients with genotypes 2 or 3[1].

Two direct-acting antiviral agents, telaprevir (TVR) and boceprevir (BOC), both of which are first generation protease inhibitors (PIs), have recently been approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 1[1,3,5]. In Brazil, the approval of these PIs has been granted exclusively for mono-infected HCV genotype 1 patients with advanced fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis of the liver[6].

Triple therapy that comprises a PI in combination with Peg-interferon alpha and RBV increases the SVR rate to approximately 70% and shortens the required treatment duration by approximately 50% in naïve patients (i.e., individuals who had not been previously treated). The SVR rates in previously treated patients depend on the response to prior treatment and the degree of liver fibrosis. Prior work has shown that this rate may vary from > 80% in previous relapse cases to approximately 15% to 30% in null responders and individuals with an advanced degree of fibrosis[1,3,7]. However, these advances occur at the expense of an increased incidence of adverse events and higher therapy costs[1,6,7].

Triple therapy for hepatitis C has been associated with a higher incidence of adverse events, a fact that can limit its tolerability. These unwanted side effects require greater monitoring of the patient compared with treatment with only Peg-interferon alpha and RBV[6,8]. The augmentation of hematological toxicity that occurs with triple therapy can also lead to a rise in the use of growth factors, which results in increased strain on the medical resources in the health system[6,7]. Furthermore, PIs carry the risk of inducing mutations that lead to HCV resistance. Extensive monitoring of patients for their virological response, attention to criteria for treatment cessation and counseling on compliance would be necessary to minimize the development of resistant variants[1].

The higher incidence of adverse events requires PI discontinuation in 10% to 21% of patients. Adverse events that occur at a higher frequency among individuals who received triple therapy include anemia, neutropenia, dysgeusia (BOC), gastrointestinal discomfort, fatigue, cutaneous eruption (TVR) and perianal discomfort (TVR)[1,6].

The present work aimed to report a case of febrile neutropenia and the development of Fournier’s Syndrome in a cirrhotic patient with HCV genotype 1 A. This patient was a null responder to two prior treatments (a change in viral load was undetectable following previous treatments, with no decrease in HCV-RNA of at least 2-log after 12 wk of treatment). The patient’s retreatment for HCV included triple therapy with BOC, Peg-interferon alpha and RBV.

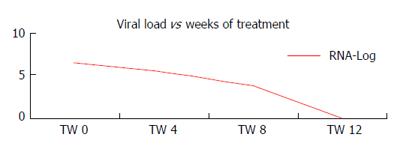

This study describes the case of a 53-year-old male with cirrhosis induced by HCV genotype 1 A. This patient was a null non-responder to two previous treatments (Peg-interferon alpha and RBV for 48 wk), and he denied the previous use of alcohol and other drugs. He was treated again with BOC, a double dose of Peg-interferon alpha [180 micrograms (μg)] and RBV. He obtained a sharp drop in viral load in the 8th week of treatment (TW 8), and viral negativity was observed in week 12 as illustrated in Figure 1.

In the 12th week of treatment (TW 12), he presented with a fever (40 °C), dyspnea and diarrhea. During the initial evaluation, he was confused and disoriented, with flapping, fever, tachypnea, arterial hypotension and tachycardia. Laboratory analyses revealed leucopenia (300 leukocytes/mm³) with neutropenia (10 neutrophils/mm³). Cefepime and filgrastim were indicated, and treatment for hepatitis C was suspended.

A myelogram demonstrated hypoplasia with cytotoxicity and maturational retardation; the chosen reposition consisted of folic acid and vitamin B12, in addition to the continuance of filgrastim.

After 48 h of antibiotic therapy, the patient started to present with bilateral erythematous lesions in the inguinal region, and these lesions evolved within 2 d with diffuse erythema throughout the perineal area extending to the root of the lower limbs, with exulcerations and an outflow of seropurulent secretions (Figure 2).

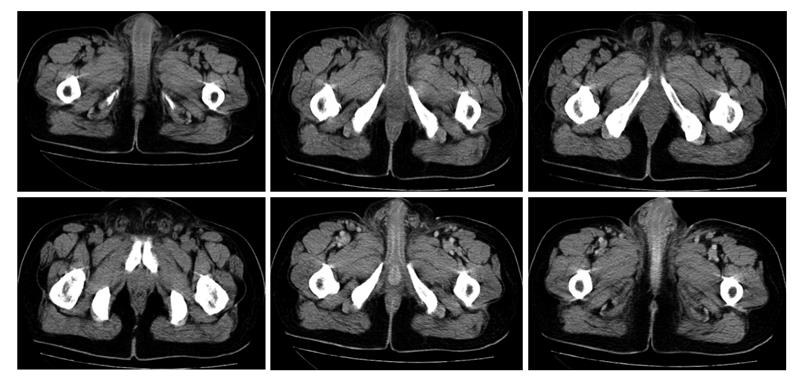

The patient underwent computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis to evaluate the depth of the lesion, and involvement of the lesion in deep planes was not observed (Figure 3). CT revealed a thickening of the skin of the inguinal region and the root of the thighs and scrotum, which was associated with a slight blurring of the adjacent fat.

Based on these symptoms, a hypothesis of Fournier’s Syndrome was postulated, and the therapy was replaced with the antibiotics imipenem, linezolid and clindamycin. The blood cultures were positive for multi-sensitive Pseudomonas, and the urine cultures were positive for Staphylococcus aureus that was sensitive to oxacillin.

The patient’s lesions regressed without requiring surgical debridement, and his neutrophil count normalized with the use of filgrastim. The patient was discharged from the hospital after 14 d of antibiotic therapy.

The advent of triple therapy for chronic hepatitis C with PIs, Peg-interferon alpha and RBV in HCV genotype 1 carriers has increased the rates of SVRs in naïve patients, previous relapsers and null responders to rates of 70%, > 80% and 30%, respectively. Nevertheless, the observed parallel increase in the incidence of adverse events limits the tolerability of this therapy and raises its associated costs[1,3,6].

The hemolytic anemia that has been associated with RBV use and the suppression of hematopoiesis observed with the use of Peg-interferon alpha require extensive monitoring of hemoglobin levels and absolute neutrophil numbers to achieve adequate management of anemia and neutropenia, two frequent adverse effects that have been related to double therapy. The frequency of these adverse events is increased in patients treated with BOC or TVR, and it results in greater reductions in the doses of RBV and/or Peg-interferon alpha, the use of growth factors or even the discontinuation of PI therapy[3,4,7].

The various dermatological manifestations associated with HCV are classified into three types according to their etiology. The first type involves the direct action of the virus on the skin, and it includes the involvement of lymphocytes, dendritic cells and blood vessels. The second type occurs secondary to the interruption of the immune response, and the third type involves a non-specific cutaneous response secondary to HCV involvement in other organs[9-11].

Interferon has the clinical potential to cause adverse effects on the skin, and these effects are secondary to interferon’s immunomodulatory activity[9-11].

The well-described association of adverse dermatological events with the use of TVR is less evident when BOC is chosen. Light-to-moderate cutaneous eruptions can be treated with oral antihistamines and/or topical corticosteroids, but TVR therapy must be terminated immediately for severe cutaneous eruptions (> 50% of the body surface area) or any eruption associated with significant systemic symptoms, including evidence of the involvement of internal organs, facial edema, mucosal erosions or ulcers, target lesions, epidermal dislocation, vesicles or blisters. For these types of serious adverse effects, the patient must be immediately referred for dermatological medical assistance. Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms Syndrome and Stevens Johnson Syndrome occur in < 1% of patients treated with TVR[1,3,11].

The increase in the neutropenia incidence [absolute neutrophil count (ANC) < 750 per cubic millimeter] is similar in patients treated with TVR, Peg-interferon and RBV compared with patients treated only with Peg-interferon and RBV. However, higher costs are incurred among the more severe cases when the proposed scheme includes BOC, Peg-interferon and RBV. Approximately 23% of patients treated with BOC had grade 3 neutropenia (ANC between 500 and 750 per cubic millimeter), and approximately 7% of these individuals experienced grade 4 neutropenia (ANC < 500 per cubic millimeter) in comparison with 13% and 4%, respectively, in patients who received Peg-interferon and RBV. It may be necessary to reduce the Peg-interferon doses and to use granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients treated with BOC[3].

There are no reports in the literature that have reported the appearance of Fournier’s Syndrome with triple therapy for HCV. However, it should be taken into consideration that this rare condition is most common in patients with diabetes, alcohol abusers and in immunosuppressed individuals. Although this diagnosis would be made primarily using clinical data, imaging exams may be useful in cases of atypical presentation or when there is concern regarding the true extent of the disease. The most common sites of involvement are the genitourinary tract, the lower gastrointestinal tract and the skin. Fournier’s Syndrome is a mixed infection caused by both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria; thus, the management of Fournier’s Syndrome requires immediate debridement and wide-spectrum antibiotic therapy[11-15].

The present case report documents severe neutropenia associated with a serious infection, Fournier’s syndrome, during triple therapy for HCV. Given the seriousness of the adverse events and the good patient outcomes observed with this treatment paradigm, this case report may have extremely important implications for patient care.

A 53-year-old cirrhotic patient with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 A who had exhibited no response to prior treatment was initiated on retreatment with boceprevir (BOC), Peg-interferon (at a double dose of 180 μg) and ribavirin (RBV). However, he exhibited fever and signs of hepatic encephalopathy during the 12th week of treatment.

The patient exhibited fever (40 °C), dyspnea, diarrhea, confusion and disorientation, flapping, tachypnea, hypotension, tachycardia and evolving diffuse erythema throughout the perineal area to the root of the lower limbs, with exulcerations and seropurulent secretions.

Septic shock and an infection of the gastrointestinal tract were also considered.

Leucopenia (300 leukocytes/mm³) with neutropenia (10 neutrophils/mm³) was diagnosed based on laboratory results.

A computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed a thickening of the skin in the inguinal region, the roots of the thighs and the scrotum, and these features were associated with a slight blurring of the adjacent fat.

A myelogram demonstrated hypoplasia with cytotoxicity and maturational retardation.

The patient was initially treated with cefepime and filgrastim after the cessation of treatment for hepatitis C. This treatment was subsequently exchanged for treatment with the antibiotics imipenem, linezolid and clindamycin.

Triple therapy for hepatitis C has been previously shown to increase the rate of sustained virological responses (SVRs), and we observed an increase in the frequency and severity of adverse events related to this treatment.

Triple therapy for hepatitis C involves the use of PIs (BOC-boceprevir/telaprevir-telaprevir) in combination with Peg-interferon and RBV, and it should be considered for early treatment viral kinetics to treatment previously performed. Naïve: a patient who has not received prior treatment; Relapser: a patient characterized by undetectable levels of HCV-RNA after an initial treatment, without a SVR because of a positive viral load after the discontinuation of treatment; Partial responder: a patient whose HCV-RNA levels fell by more than 2-log after 12 wk of treatment, but HCV-RNA levels were detectable at the end of the treatment period; null responder: a patient whose HCV-RNA levels fell at least 2-log after 12 wk of treatment.

The case report presented here describes a serious adverse event associated with this new triple therapy that has not yet reported in the literature. The authors’ data emphasize the importance of adequate patient management plans that are in accordance with international clinical protocols, and these findings allow experts to gain access to and experience with the conduct of this real-life case.

Dr. Oliveira et al presented an interesting case report. The design of the study is adequate. The finding of the presented case report is of interest for the general reader.

P- Reviewer: Koch-Institute R S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Swiss Association for the Study of the Liver. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 with triple therapy comprising telaprevir or boceprevir. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13516. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Pawlowska M, Pilarczyk M, Foksinska A, Smukalska E, Halota W. Hematological Adverse events and Sustained Viral Response in Children Undergoing Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:968-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yee HS, Chang MF, Pocha C, Lim J, Ross D, Morgan TR, Monto A. Update on the management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and the National Hepatitis C Program Office. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:669-689; quiz 690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sulkowski MS, Poordad F, Manns MP, Bronowicki JP, Rajender Reddy K, Harrison SA, Afdhal NH, Sings HL, Pedicone LD, Koury KJ. Anemia during treatment with peginterferon Alfa-2b/ribavirin and boceprevir: Analysis from the serine protease inhibitor therapy 2 (SPRINT-2) trial. Hepatology. 2013;57:974-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Picard O, Cacoub P. Dermatological adverse effects during genotype-1 hepatitis C treatment with the protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir. Patient management. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:437-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Protocolo clinico e diretrizes de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Brasilia: Ministerio da Saude 2013; . |

| 7. | Kwo PY. Boceprevir and treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;17:63-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burger D, Back D, Buggisch P, Buti M, Craxí A, Foster G, Klinker H, Larrey D, Nikitin I, Pol S. Clinical management of drug-drug interactions in HCV therapy: challenges and solutions. J Hepatol. 2013;58:792-800. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jadali Z. Dermatologic manifestations of hepatitis C infection and the effect of interferon therapy: a literature review. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:43-48. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Berk DR, Mallory SB, Keeffe EB, Ahmed A. Dermatologic disorders associated with chronic hepatitis C: effect of interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:142-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cacoub P, Bourlière M, Lübbe J, Dupin N, Buggisch P, Dusheiko G, Hézode C, Picard O, Pujol R, Segaert S. Dermatological side effects of hepatitis C and its treatment: patient management in the era of direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol. 2012;56:455-463. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bhatnagar AM, Mohite PN, Suthar M. Fournier’s gangrene: a review of 110 cases for aetiology, predisposing conditions, microorganisms, and modalities for coverage of necrosed scrotum with bare testes. N Z Med J. 2008;121:46-56. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Morua AG, Lopez JA, Garcia JD, Montelongo RM, Guerra LS. Fournier’s gangrene: our experience in 5 years, bibliographic review and assessment of the Fournier’s gangrene severity index. Arch Esp Urol. 2009;62:532-540. [PubMed] |