Published online Apr 27, 2013. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i4.226

Revised: September 25, 2012

Accepted: November 17, 2012

Published online: April 27, 2013

Processing time: 262 Days and 6.1 Hours

Giant cell hepatitis (GCH) with autoimmune hemolytic anemia is a rare entity, limited to young children, with an unknown pathogenesis. We report the case of 9-mo old who presented with fever, diarrhea and jaundice four days before hospitalization. Physical examination found pallor, jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly. The laboratory workup showed serum total bilirubin at 101 μmol/L, conjugated bilirubin at 84 μmol/L, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-C3d positive direct Coombs’ test. The antinuclear, anti-smooth muscle and liver kidney microsomes 1 non-organ specific autoantibodies, antiendomisium antibodies were negative. Serological assays for viral hepatitis B and C, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex and Epstein Barr virus were negative. The association of acute liver failure, Evan’s syndrome, positive direct Coomb’s test of mixed type (IgG and C3) and the absence of organ and non-organ specific autoantibodies suggested the diagnosis of GCH. The diagnosis was confirmed by a needle liver biopsy. The patient was treated by corticosteroids, immunomodulatory therapy and azathioprine but died with septicemia.

- Citation: Bouguila J, Mabrouk S, Tilouche S, Bakir D, Trabelsi A, Hmila A, Boughammoura L. Giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a nine month old infant. World J Hepatol 2013; 5(4): 226-229

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v5/i4/226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v5.i4.226

Giant cell hepatitis (GCH) associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AHA) is a rare individualized entity, particularly affecting infants, with an unknown pathogenesis and poor outcome[1,2]. Only 27 cases have been reported in pediatric reviews[2-6]. It usually presents as a severe hepatitis, jaundice and fever that begins about 1 year of age and is associated with AHA with a positive direct Coombs’ test[3]. In this article, we describe a new case in a nine month old infant who presented with pallor, fever and jaundice and whose outcome was severe in spite of early treatment. We also review literature data concerning clinical presentation and therapeutic modalities of this rare entity.

A 9-mo old infant with no pathological medical history presented with jaundice, fever and watery diarrhea for the last 4 d. Physical examination showed a eutrophic, febrile (38.3 °C) infant. Jaundice was obvious with pallor, hepatomegaly (liver span of 11 cm) and enlarged spleen. Laboratory features (Table 1) showed a bicytopenia: normochromic normocytic regenerative anemia and thrombocytopenia, associated with hepatic insufficiency, cytolysis and cholestasis with elevated conjugated bilirubin and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase. Alpha fetoprotein (AFP) was high as well.

| J1 of hospitalization | J10 of hospitalization | J17 treatment | J60 treatment | |

| Leucocytes (elements/μL) | 12400 | 19800 | 23300 | 27800 |

| PNN (%) | 77 | 42 | 60 | 57 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.3 | 6.8 | 11.4 | 10.4 |

| MCV | 79.9 | 86.6 | 85.4 | 96.6 |

| Reticulocytes (elements/μL) | 114000 | 17600 | 92300 | 184000 |

| Platelets (elements/μL) | 71000 | 7000 | 153000 | 152000 |

| SAT/ALT (UI/L) | 1020/810 | 1430/1886 | 368/600 | 1310/522 |

| Total bilirubin | 101 | 425 | 190 | 425 |

| Direct bilirubin (μmol/L) | 82.6 | 122 | 78 | 291 |

| GGT (UI/L) | 170 | 122 | 34 | |

| PT (%) | 55 | 51 | 70 | 20 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 42 | - | 12 | 20 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 179 | 29 | 29.63 | |

| LDH (UI/L) | 2089 | 1092 | 400 | - |

| Haptoglobin (g/L) | 0.6 | 0 | - | - |

| DCT | - | + à IgG/C3d | - | + à IgG/C3 |

| Ferritinemia (ng/mL) | 163 | - | - | - |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3.3 | - | - | - |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 3.99 | - | - | - |

With this association of a febrile jaundice with liver injury, infectious causes were first suspected. Serologies of hepatitis A, B and C, of cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus, herpes simplex virus and human immunodeficiency virus were all negative. A metabolic cause, particularly tyrosinemia, was also evoked given the elevated levels of AFP and delta-aminolevulinic acid (12.08 mg/mL); this diagnosis was also ruled out since the amino and organic acids chromatographies were normal. We also sought for an autoimmune hepatitis, given the presence of bicytopenia, but anti-mitochondrial, anti-LKM1, anti-nuclear and anti smooth muscle were absent. Immune system screening revealed high immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (11.4 g/L) and low complement fractions (C3 = 0.73 g/L and C4 = 0.04g/L). Cellular immunity was normal.

On the other hand, an Escherichia Coli (E. Coli) was detected in both urine and blood cultures. This infection was handled with adequate intravenous antibiotics. Abdominal ultrasonography showed an enlarged hyperechogenous liver, a homogenous splenomegaly, normal non dilated biliary ducts and the presence of a hyperechogenous cuff surrounding the hepatic pedicle.

Initially, there was no positive progression as fever persisted and both jaundice and pallor worsened. At day 10 of hospitalization, hemoglobin decreased down to 6.8 g/dL (normocytic normochromic regenerative anemia) and platelets were at 6000 elements/μL. Haptoglobin was null and direct Coombs’ test was positive (IgG and C3d).

The association of hepatic insufficiency and AHA in a young infant on one hand and the absence of auto-antibodies on the other hand, made us consider the diagnosis of GCH. Thus, a liver biopsy was performed after blood and platelet transfusions and the patient’s stabilization.

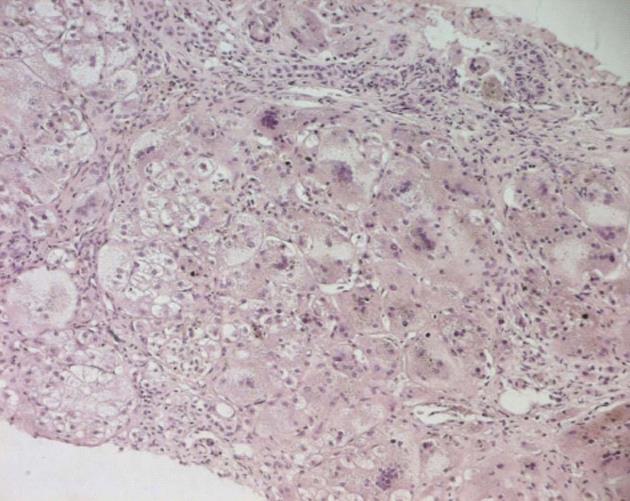

Histological analysis confirmed the diagnosis; there was a diffuse transformation of hepatic cells into giant cells with areas of necrosis (Figure 1).

The patient first received an intravenous immunoglobulin course at the dose of 1g/kg per day during 2 d, then both steroids (prednisone: 2 mg/kg per day) and immunosuppressive [Azathioprine (Imurel®): 1 mg/kg per day] therapies were started.

The immediate course was favorable, with clinical as well as biological improvement since day 17 of steroid therapy (Table 1). At day 30 of hospitalization, the infant was discharged from hospital under the same treatment. He was seen 15 d later with stable biological data.

However, he was hospitalized again 60 d after the onset of the therapy, with fever, edema and ascites. We found a urinary tract infection with identification of a multiresistant E. Coli, hepatic insufficiency [prothrombin time (PT) = 20%] and aggravation of the cytolysis (Table 1). The patient received intravenous antibiotics. Liver insufficiency was handled with symptomatic measures. In spite of this management, fever persisted, renal failure appeared and liver function worsened (PT = 12%). The infant died with septic shock. Follow up had lasted 3 mo since the beginning of symptoms.

GCH associated with AHA was described in 1981 in young children with a severe presentation and high mortality (39% of reported cases)[4]. This pathological entity is rare[1,2]. 27 cases have been reported in pediatric reviews[2,4-6]. In 2011, an Italian pediatrician’s team reported the biggest series of cases of this pathology. They described 16 children during a 28-year period[4].

The pathogenesis of this entity is still unknown[1]. Several authors have suggested an autoimmune origin, especially in the presence of AHA and hypergammaglobulin levels[1].

According to Maggiore et al[4], elements suggesting an autoimmune origin among their 16 patients were a positive family history of autoimmune conditions, such as type 1 diabetes, thyroiditis and psoriasis, positive findings for auto-antibodies in some patients, thrombocytopenia, the improvement under immunosuppressive therapy and the decline when tapering doses. However, this hypothesis is not approved by other authors since auto-antibodies are often absent and there is no typical histological evidence of autoimmune hepatitis[2]. Another hypothesis suggests that the underlying mechanism could be a non controlled release of cytokines by activated T lymphocytes as well as Küppfer cells[2]. In the present case, we found neither family nor personal history of autoimmune disease; however, there was an initial positive response to steroids as well as immunosuppressive therapy.

GCH associated with AHA specifically occurs in young infants; the first signs often begin between 2.5 and 24 mo of age[4,5]. In our patient, the first signs were seen at 9 mo. Hepatocyte transformations into giant cells can happen during the neonatal period and is considered a non specific reaction of immature hepatocytes to various aggressions[4].

Each time hepatitis is associated with AHA with positive Coombs’ test, either with IgG or complement, in an infant, liver biopsy must be performed as soon as possible in order to confirm the diagnosis of GCH so that early treatment can be started[4]. The prognosis of this pathology is often poor[7]. Our patient had an early relapse and died of septic shock.

Treatment possibilities include steroids and/or azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, intravenous immunoglobulins, mercaptopurine, mycophenolate mofetil, vincristine, plasmapheresis and anti CD20 (Rituximab®)[1]. Splenectomy was also proposed in some patients as an alternative for AHA resistant to medical treatment[1,8].

In the biggest reported series in the literature, initial treatment was based on prednisone (2-3 mg/kg per day) and azathioprine (1-2 mg/kg per day) in 13 out of 16 cases. With the association of cyclosporine in the 3 remaining cases, the latter had a severe presentation[4]. Total remission with a normalized transaminases level was reached in 8 cases/16. Remission was partial in 6 cases/16 and absent in the 2 remaining cases[4]. Relapse occurred in 11 patients, 10 of whom presented an AHA resistant to medications. Anti CD20 were successfully used in 2 patients and splenectomy was performed in 5 cases/10; only 2 of them got positive results[4].

In this series, 4 patients died because of severe sepsis and post transplantation, respectively in 3 and 1 cases. The other patients (12 cases) are alive and one underwent liver transplantation[4]. This series illustrates the severity of this pathology and the difficulties of treatment, given the high risk of relapse as well as therapy resistant AHA after relapse. Liver transplantation was reported in 6 patients in the literature; 3 cases relapsed after transplantation[4].

In our patient, we started therapy by an intravenous course of immunoglobulins followed by the association of prednisone and azathioprine with partial response (improvement without normalization of transaminases). Relapse was rapid (less than 4 mo) with severe hepatic insufficiency but without recurrence of hematological disorders. Our patient died due to septic shock.

In conclusion, GCH associated with AHA is a severe pathological entity. This diagnosis should be evoked when hepatitis of unknown origin occurs in an infant and will be confirmed by liver biopsy. Early treatment associating corticotherapy and immunosuppressive drugs with sufficient doses is essential to reach total remission with normal transaminases. Treatment must be maintained as long as possible in order to avoid relapses which are more resistant to therapies.

P- Reviewer de Oliveira CPMS S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Vajro P, Migliaro F, Ruggeri C, Di Cosmo N, Crispino G, Caropreso M, Vecchione R. Life saving cyclophosphamide treatment in a girl with giant cell hepatitis and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia: case report and up-to-date on therapeutical options. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:846-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rovelli A, Corti P, Beretta C, Bovo G, Conter V, Mieli-Vergani G. Alemtuzumab for giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:596-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bouyahia O, Mrad-Mazigh S, Boukthir S, El Gharbi-Sammoud A. Les maladies autoimmunes du foie chez l’enfant. Rev Maghr Pediatr. 2008;28:59-66. |

| 4. | Maggiore G, Sciveres M, Fabre M, Gori L, Pacifico L, Resti M, Choulot JJ, Jacquemin E, Bernard O. Giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in early childhood: long-term outcome in 16 children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:127-132.e1. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Miloh T, Manwani D, Morotti R, Sukru E, Shneider B, Kerkar N. Giant cell hepatitis and autoimmune hemolytic anemia successfully treated with rituximab. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:634-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kashyap R, Sarangi JN, Choudhry VP. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in an infant with giant cell hepatitis. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:199-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hartman C, Berkowitz D, Brik R, Arad A, Elhasid R, Shamir R. Giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia and hemophagocytosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:330-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Choulot JJ, Parent Y, Etcharry F, Saint-Martin J, Mensire A. [Giant cell hepatitis and autoimmune hemolytic anemia: efficacy of splenectomy on hemolysis]. Arch Pediatr. 1996;3:789-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |