Published online Mar 27, 2013. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i3.152

Revised: October 28, 2012

Accepted: November 17, 2012

Published online: March 27, 2013

Sporadic cases of acute viral hepatitis E have been described in developed countries, despite the more common occurrence in endemic areas and developing countries. We present the case of a 58 years old Portuguese female, with no epidemiological relevant factors, admitted with acute hepatitis with positive anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibody and high serum gamma globulin (> 1.5 fold increase). Serologies for hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hereditary sensory neuropathy and varicella zoster virus were negative. Liver biopsy histology revealed changes compatible with autoimmune hepatitis. Prednisolone and azathioprine was started. She tested positive for immunoglobulin M anti hepatitis E virus (HEV) with detectable viremia by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technique. HEV-RNA was confirmed through RT-PCR in a liver specimen, establishing the diagnosis of acute hepatitis E. Immunosuppression was stopped. She clinically improved, with resolution of laboratory abnormalities. Therefore, we confirmed acute hepatitis E as the diagnosis. We review the literature to elucidate about HEV infection and its autoimmune effects.

- Citation: Vieira CL, Baldaia C, Fatela N, Ramalho F, Cardoso C. Case of acute hepatitis E with concomitant signs of autoimmunity. World J Hepatol 2013; 5(3): 152-155

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v5/i3/152.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v5.i3.152

Acute hepatitis can result from a variety of etiologies, which include viral [hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis D virus, hepatitis E virus (HEV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus] etiologies, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), non alcoholic steatohepatitis, toxins and metabolic disorders, like Wilson’s disease. Epidemiology is an important factor. HEV, an enterically transmitted virus, occurs mainly in developing countries. Swine seem to function as a reservoir for HEV. The majority of cases have been reported in pregnant women, immunosuppressed patients and in those with contact with swine. However, recent data suggest that the HEV could be more widespread than previously thought, with more sensitive tests increasing detection rates[1]. Cases of sporadic HEV have also been described[1]. To diagnose AIH using the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) score for AIH, the exclusion of other etiologies is required before classifying AIH as probable or definitive[2]. When using the recent simplified criteria for AIH[3], the exclusion of viral etiology is one of the 4 criteria, together with liver histology, gamma globulin level and antibody markers [anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), liver kidney microsomal (LKM), soluble liver antigen (SLA)]. More sensitive and accurate tests used for screening for viral etiologies may lead to reclassification of some cases of AIH as being of viral etiology. Two cases of AIH were reclassified as HEV after obtaining the HEV status[4,5]. However, false positive results for anti-HEV have been reported in patients with AIH. In 1997, the Virology Institute of Tour, France, reported that the ABBOT method showed 13% positive results for anti-HEV in chronic AIH which turned out to be negative using the synthetic-peptide based test[6]. Therefore, in a patient presenting as an acute hepatitis and previously considered as being of autoimmune etiology, a positive result of anti-HEV requires the use of more accurate tests, determining viremia or liver immunohistochemistry markers in order to rule out false positive results. We present the case of a patient with acute hepatitis that, according to the IAIHG score, was considered to be a probable AIH, which turned out to be positive for anti-HEV with detectable viremia.

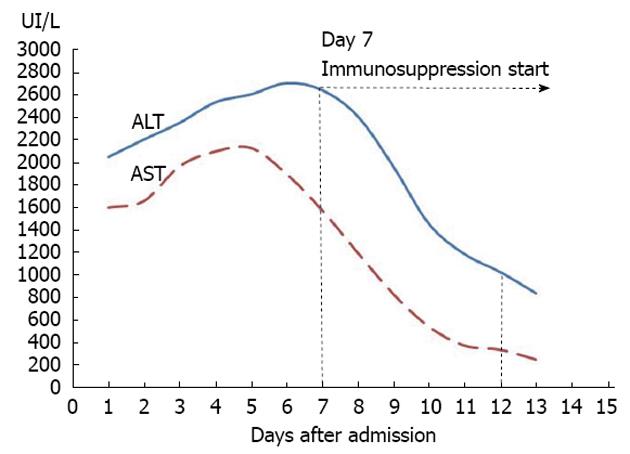

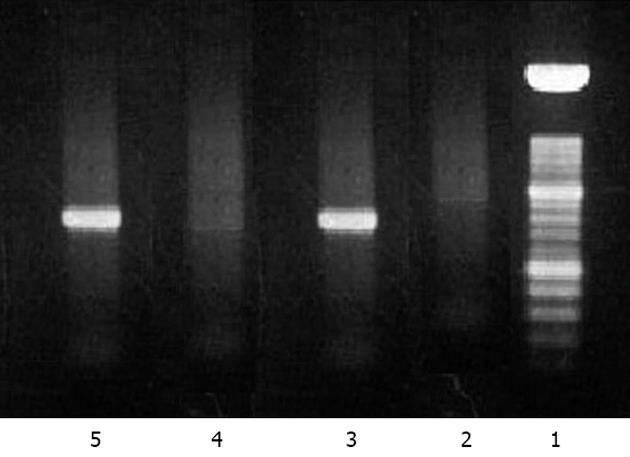

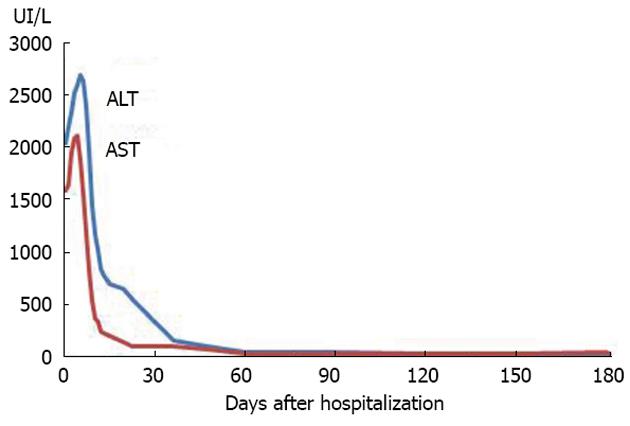

A 58 years old female Caucasian patient was admitted to our hospital with a history of progressive fatigue and anorexia over 6 wk and markedly increased liver enzymes. She had a past medical history of rheumatic fever, with normal cardiac function, nephrolithiasis, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, major depression and recent traumatic fracture of the wrist (3 mo before), medicated with venlafaxine, mirtazapine, lisinopril, nebivolol, bromazepam and diclofenac (last taken 3 mo before admission and maximum 1 per day). She had no history of contact with animals or previous stays in regions endemic for hepatotropic viruses, and mentioned regular swine meat ingestion. There was no history of immunosuppressive therapy. On examination, she was apyretic and subicteric. There was no evidence of clinical encephalopathy, pruritus, dermatological lesions, hemorrhagic dyscrasia or abdominal pain. Laboratory analysis showed altered liver enzymes with aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 2088 IU/L (0-34); alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 2638 IU/L (10-49); alkaline phosphatase 233 IU/L (45-129); gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 197 IU/L (< 38); total bilirubin 3.17 mg/dL (< 1.0); prothrombin time 13.7/11.6 s; V factor 122% (50-100); VII factor 40% (70-130); gamma globulin 3.15 g/dL (0.68-1.60); and immunoglobulin G (IgG) 3850 mg/dL (700-1600). The serological tests for autoimmune hepatitis revealed positive ANA (titer 1:320 with cytoplasmic pattern); anti-DsDNA (824 IU/mL; < 200); ASMA positive, thyroid auto-antibodies, type anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody (243 IU/mL; < 50) with negative tests for anti-liver kidney microsomal, anti-myocardial antibody, SSA, single-strand binding protein, ribonucleoprotein, HS70 and JO1. Viral serology was negative for HAV [IgM (-); IgG (-)], EBV [IgM (-); IgG (-)], CMV [IgM (-); IgG (-)], HBV (AgHBs, AgHbe, AcHBc, antiHBs), negative anti-HCV with undetectable RNA of HCV and HIV antigens types 1 and 2 both negative. Serological tests for Coxiella burnetti and leptospirosis were negative. Tests for iron and copper metabolic disorders were negative. Laboratory tests showed normal alpha1 antitrypsin complement and IgG4 levels. Thyroid function tests were also normal. The abdominal Doppler ultrasound was normal. A percutaneous liver biopsy was performed and compatible with autoimmune hepatitis, revealing intense interface hepatitis, with lymphoplasmacytic portal, septal and acinar infiltrate with focal hepatocellular necrosis and areas of periportal fibrosis. The patient did not have an epidemiological history favoring HEV and, prior to knowing its results, the IAIHG pre-treatment score was 14 points considering a negative viral study [female sex (+2); ALP/AST < 1.5 (+2); IgG > 2 × normal upper limit (+3); ANA > 1:80 (+3); negative AMA; alcohol intake < 25 g/d (+3); hepatotoxic drugs present (-4); interface hepatitis (+3)]. As the patient met the absolute criteria with AST, ALT > 10 × the upper limit of normal, a diagnosis of type 1 AIH was considered and therapy was started on day 7[7]. Retrospectively, we realized that both the AST and ALT levels (Figure 1) were already slowly decreasing 24 h before the immunosuppressive therapy was started. After one week on prednisolone 30 mg/d and azathioprine 50 mg/d, there was a significant reduction in the laboratory values: AST 245 U/L; ALT 835 U/L; ALP 148 U/L; GGT 214 U/L; total bilirubin 1.06 mg/dL; prothrombin time 12.5/11.6 (Figure 1, day 12). She was discharged with the combined immunosuppressive treatment for AIH. There was a progressive improvement of symptoms. One month after discharge, she was asymptomatic with normal total bilirubin (0.67 mg/dL) and gamma globulin (1.25 g/dL) but AST and ALT were still > 2 × the upper limit (AST 94 U/L; ALT 158 U/L). The results of serological tests for HEV were obtained after the patient was discharged. The patient had positive IgM serology for HEV and negative serology for IgG. The tests were performed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method by MP Biomedicals (IgM determination: sensitivity 95.8%; specificity 97.6%). Positive viremia was detected by real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) but not quantified. This technique has an overall sensitivity of 98% with 100% specificity and uses a primer targeting the ORF2 protein. The sample was processed with the MagnaPure system (Roche) and amplified with StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems). To complete the study, HEV RNA was extracted from liver tissue using Roche MagnaPure kit (Indianapolis, United States). Two sets of primers for reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and nested PCR were synthesized by TIBMol, based on the highly conserved region of HEV ORF 2 of the United States (GenBank accession No. AF060668 e AF060669), Japanese (AB089824), Burmese (M73218 and D10330) and Korean swine (AF516178, AF516179, and AF527942) strains. RT-PCR was performed using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit for RT-PCR (AMV) from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Figure 2 demonstrates the positive detection of HEV-RNA. Serotype determination was not available at the laboratory. Therefore, the detectable viremia and the positive molecular testing in liver biopsy allowed the diagnosis of acute hepatitis E in our patient. The patient was reassessed at the outpatient clinic nearly two months after hospitalization. She was asymptomatic and because of the positive tests for HEV, immunosuppressive therapy was stopped. HLA study revealed a DRB1*03 subtype. Nearly 6 mo after hospitalization, AST, ALT, gamma globulin, ANA, anti DsDNA and ASMA were within normal range, after more than 4 mo with no immunosuppression treatment (Figure 3 and Table 1). First day, the serum gamma globulin was 3.15 g/dL; 30 d, the serum gamma globulin was 3.0 g/dL; 90 d, 1.5 g/dL; 180 d, 1.4 g/dL. The serum gamma globulin levels evolved over time, with normal values 6 mo after the admission under no immunosuppression. The patient remained asymptomatic during the 6 mo follow up period.

| Day after admission | ANA; anti DsDNA titers (UI/mL) |

| 0 | 1/320; 840 |

| 30 | 1/160; 520 |

| 90 | Negative; < 200 |

| 180 | Negative; < 200 |

In the clinical setting of an acute hepatitis, according to the IAIHG score, the positive serologies for ANA, ASMA, high immunoglobulin and a compatible liver histology added up to a score of 14 points, which suggests a probable diagnosis for AIH. Even without considering the 3 points given for the viral negativity, the score would still be suggestive of probable AIH. Our patient improved, both clinically and biochemically on immunosuppressive treatment. The positivity for thyroid auto-antibodies favored a diagnosis of autoimmune disease. However, the improvement could be coincident with a self-limited viral hepatitis with a gradual recovery course, considering that both AST and ALT values started to decrease before the therapy was started. Sporadic cases of HEV in non-endemic areas are rare[1]. The patient’s history and previous health status were not suspicious for viral hepatitis E. There have been case reports on the effect of HEV in cirrhotic patients and false positive results of anti-HEV antibodies in patients with chronic liver disease of autoimmune etiology[6]. However, our patient had no evidence of liver cirrhosis. The presence of detectable viremia and positive liver molecular biology confirmed the diagnosis of hepatitis E infection. There are several relevant issues which arise because of this patient. Firstly, even in non-endemic areas, HEV must be considered in the differential diagnosis when approaching a patient with an acute hepatitis. Secondly, if a patient tests positive for IgM, it can be a false positive result and viremia and/or molecular liver histology and immunohistochemical testing should be performed. IgM and IgG titers and their evolution in serial analysis could also be used to determine the hepatitis time frame. Viremia is detectable for 4 mo and is better determined with real-time PCR techniques. Compared to single and nested gel-based RT-PCR, the various real-time PCR assays have a higher sensitivity, are less laborious, save time and are less prone to cross contamination. Thirdly, it is known that a minority of patients (3%-5%) with chronic AIH can present with low HEV viremias[6], highlighting the possibility of HEV also being a trigger for the development of AIH. Also, one must consider the possibility of HEV inducing serological abnormalities such as hyperimmunoglobulinemia, possibly through polyclonal stimulation mimicking AIH[5]. The anti-DSDNA positivity in our patient, with no other criteria for systemic lupus erythematosis[8], could be interpreted as a non-specific crossed reaction finding. Although we gave the diagnosis of a viral hepatitis E infection in our patient, follow up will be necessary to determine if the serological and histological findings were due to mechanisms of non-specific reactions to a viral infection or even a specific reaction to a specific HEV strain that could trigger AIH in the future. Also, reassessing serology and serum HEV RNA detection through RT-PCR could be of value to characterize this case as an acute episode with spontaneous virological clearance or evolution to chronic hepatitis E, as it is now well known that this can occur, although mainly in transplanted livers. Acute hepatitis E can evolve to hepatic failure and ribavirin in monotherapy use has been reported in some patients to avoid the need for liver transplantation. In the setting of chronic hepatitis E in liver transplanted patients, after failure of immunosuppression reduction, ribavirin monotherapy for a minimum period of 3 mo is advised in order to clear the virus, through mechanisms yet not fully understood[9]. Given the normalization of symptoms and laboratory parameters and considering the high cost of the serological and PCR techniques used at our institution, and also considering the high diagnostic accuracy of the tests used during work up, we did not reassess the HEV RNA determination at 6 mo. In 1991, hepatitis A was identified as a trigger for autoimmune chronic hepatitis type 1 in individuals with a familial history of AIH. Our patient was a case of HEV and had no familial history of autoimmune diseases. However, the authors elucidated the mechanism through which virus could trigger AIH, besides molecular mimicry. In this case, HEV induced a defect in suppressor-inducer T lymphocytes specific for the asialoglycoprotein receptor, a surface receptor of the hepatocyte, which increases in HAI and induces cell inflammation[10].

In conclusion, HEV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an acute hepatitis, even in patients with a possible diagnosis of AIH. Further studies are needed to understand the interaction between AIH presenting as acute hepatitis and viral hepatitis E infection.

We thank all the co-workers with Carlos Cardoso, from the Joaquim Chaves Laboratories and the Department of Pathology of Hospital Santa Maria, Lisbon, for their contribution.

P- Reviewers Tacke F, Bonino F S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Pina S, Buti M, Cotrina M, Piella J, Girones R. HEV identified in serum from humans with acute hepatitis and in sewage of animal origin in Spain. J Hepatol. 2000;33:826-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, Chapman RW, Cooksley WG, Czaja AJ, Desmet VJ. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2003] [Cited by in RCA: 1986] [Article Influence: 76.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1253] [Article Influence: 73.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nagasaki F, Ueno Y, Kanno N, Okamoto H, Shimosegawa T. A case of acute hepatitis with positive autoantibodies who actually had hepatitis E virus infection. Hepatol Res. 2005;32:134-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nagasaki F, Ueno Y, Mano Y, Igarashi T, Yahagi K, Niitsuma H, Okamoto H, Shimosegawa T. A patient with clinical features of acute hepatitis E viral infection and autoimmune hepatitis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;206:173-179. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Le Cann P, Tong MJ, Werneke J, Coursaget P. Detection of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in patients with autoimmune chronic active hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:387-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, Krawitt EL, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Vierling JM. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:2193-2213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1039] [Cited by in RCA: 1010] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7731] [Cited by in RCA: 8660] [Article Influence: 309.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wedemeyer H, Pischke S, Manns MP. Pathogenesis and treatment of hepatitis e virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1388-1397.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vento S, Garofano T, Di Perri G, Dolci L, Concia E, Bassetti D. Identification of hepatitis A virus as a trigger for autoimmune chronic hepatitis type 1 in susceptible individuals. Lancet. 1991;337:1183-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |