Published online Dec 27, 2013. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i12.692

Revised: October 29, 2013

Accepted: December 9, 2013

Published online: December 27, 2013

Processing time: 128 Days and 17.9 Hours

Acute cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a commonly encountered complication in the post liver transplant setting. We present a case of a 71-year-old male with acute CMV infection, initially presenting with a gastrointestinal bleed due to acute CMV gastritis and later on complicated by acute venous thromboembolism occurring as an unprovoked event in the post liver transplant period. Traditional risk factors for venous thromboembolism have been well described in the medical literature. Sporadic cases of thromboembolism due to CMV infection in the immune compromised patients have been described, especially in the post kidney transplant patients. Liver transplant recipients are equally prone to CMV infection particularly in the first year after successful transplantation. Venous thromboembolism in this special population is particularly challenging due to the fact that these patients may have persistent thrombocytopenia and anticoagulation may be a challenge for the treating physician. Since liver transplantation is severely and universally limited by the availability of donor organs, we feel that this case report will provide valuable knowledge in the day to day management of these patients, whose clinical needs are complex and require a multidisciplinary approach in their care and management. Evidence and pathophysiology linking both the conditions is presented along with a brief discussion on the management, common scenarios encountered and potential impact in this special group of patients.

Core tip: Liver transplant recipients are a special group of individuals whose clinical needs are complex due to the use of immunosuppressive agents. They are prone to several opportunistic infections which are not commonly encountered in regular clinical practice. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a well-recognized complication in the post-transplant setting which can affect the graft function and increase morbidity and mortality. Venous thromboembolism occurring in the setting of acute CMV infection in this group of patients is an important complication and we attempt to delineate the pathophysiology, discuss evidence linking both the conditions and provide practical points in the management of these complex individuals.

- Citation: Edula RG, Qureshi K, Khallafi H. Acute cytomegalovirus infection in liver transplant recipients: An independent risk for venous thromboembolism. World J Hepatol 2013; 5(12): 692-695

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v5/i12/692.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v5.i12.692

Liver transplantation is a complex surgical procedure requiring extensive evaluation of these patients in the pre-transplant period and specialized care in the post- transplant period. Immunosuppression in these patients is extremely important to prevent graft loss as a result of rejection. Various complications can occur in these patients, especially in the immediate post-operative period and can include technical complications from surgery, rejection of the graft, metabolic derangements, bacterial infections and viral infections from profound immunosuppression. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in the post-transplant setting is a well-recognized complication that can affect graft function and can also predispose these patients to venous thromboembolism. Here we present a case of acute CMV infection, complicated by unprovoked deep vein thrombosis and discuss the evidence, pathophysiology and practical aspects of management.

A 71-year-old Caucasian male presented to our post transplant clinic at 6 mo post orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) for follow up. He complained of swelling of the right lower extremity for the last three days. There was no history of trauma. Physical exam revealed swelling of the right leg below knee, ankle edema and warmth with some discomfort to palpation. Acute deep vein thrombosis was suspected and venous doppler confirmed extensive deep vein thrombosis involving the profunda femoris, femoral, popliteal, anterior and posterior tibial and peroneal veins. Patient was admitted to the hospital for further management.

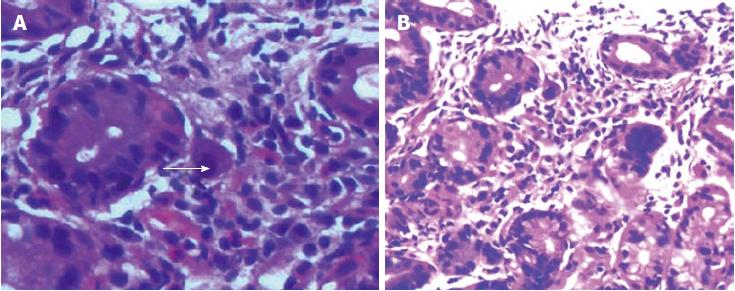

Three weeks prior to this event he was admitted to the hospital with fever, malaise, diarrhea and melena requiring blood transfusion. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy at that time revealed a clean based gastric ulcer with antral gastritis. Biopsies revealed acute gastritis with CMV inclusion bodies consistent with acute CMV infection (Figure 1). Serologies confirmed CMV IgM positive titres. He was recently taken off valacyclovir prophylaxis for CMV in the post transplant setting per protocol. Thrombophilia work up revealed increased factor VIII levels and decreased protein S activity at 28%. He did not have any risk factors for venous thromboembolism except for recent hospitalization due to gastrointestinal bleed. During that time he did not receive standard venous thromboembolism prophylaxis other than subcutaneous compression devices due to obvious bleeding. We concluded that he most likely had an unprovoked deep vein thrombosis event precipitated by acute CMV infection and performed a literature search to support our hypothesis.

A recent large prospective study reported that CMV IgM seropositivity was independently associated with increased short term risk venous thromboembolism (VTE), following adjustment for age and other confounding factors (P = 0.003). There was no clinically significant association with arterial thrombosis in the same study[1].

A case control study of immunocompetent patients with VTE revealed CMV IgG antibodies were found more frequently in patients with VTE as compared to controls (P = 0.016). The overall rate of CMV IgM antibodies detection was low but they were more often detected in cases as compared to controls. The difference was noted to be statistically significant in patients with an unprovoked VTE event (P = 0.017). With the exception of age no association was found between CMV seropositivity and established VTE risk[2].

VTE in renal transplant patients has been reported in a case series of seven patients with simultaneous acute CMV infection with no other obvious risk factors for the same[3]. Sporadic cases of venous and arterial thromboembolism in the setting of acute CMV infection have been reported in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients[4].

CMV infection a frequent complication in the post solid organ transplantation setting is known to modify endothelial phenotype from anticoagulant to procoagulant state[3]. Various potential causative mechanisms that may act directly on the vessel wall or indirectly by triggering thrombosis, have been proposed as the reason for CMV associated thrombosis. IE84 a gene product of CMV binds to and inhibits P53 mediated apoptosis, increasing smooth muscle proliferation and increased risk for thromboembolism[5]. Other mechanisms involve CMV enhanced platelets and leukocyte adhesion to infected endothelial cells, effects mediated by activating factor X, factor VIII and triggering thrombin generation[6]. The most accepted theory supported by several in-vitrio studies conclude that CMV transiently induces production of anti-phospholipid antibodies which is a well known risk factor for venous and arterial thromboembolism[7]. The possible role of other factors associating infection with VTE as an independent risk, decreased physical activity and prolonged fever following acute CMV infection leading to dehydration can explain this observation[1]. CMV IgG positive serostatus was linked to an unexplained factor VIII elevation and other procoagulant factors like fibrinogen, which again can trigger thromboembolism[8,9].

Due to a recent history of upper gastrointestinal bleed from a pyloric channel ulcer and risk for rebleeding with anticoagulation our patient underwent inferior vena cava filter placement. Repeat endoscopy as a follow up for recently diagnosed gastric ulcer due to the need for anticoagulation revealed normal mucosa with complete healing of the pyloric channel ulcer. Due to the extent and severity of VTE, after weighing the risks and benefits of anticoagulation, he was initiated on anticoagulation with warfarin and low molecular weight heparin overlap per standard protocol. For his acute CMV infection he was initiated on oral valacyclovir after initial diagnosis and is symptom free at follow up.

Acute CMV infection in the post OLT setting is a well-known complication. It can be asymptomatic or manifest at 2-12 mo post OLT with features that may include fever, malaise, diarrhea, increase in aminotransferases, cytopenias, retinitis and pneumonitis[10]. High risk patients include those who are CMV recipient negative and receive a CMV positive donor liver. It can also result from reactivation of prior infection in a recipient[10].

Patients with end stage liver disease who undergo OLT have severe coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia prior to and in the immediate post-operative period. This usually recovers within the next few days to weeks post transplantation. Thrombocytopenia may persist for several months or may never recover due to severe pre-transplant hypersplenism. Immunosuppressive agents and prophylactic medications for opportunistic infections may contribute to cytopenias, which include persistent thrombocytopenia in the post-transplant period. VTE prophylaxis in these patients with low molecular weight heparin is usually contraindicated due to the high risk for bleeding complications that may affect graft survival and increase morbidity and mortality. These patients are at high risk for hospitalization in the first few months post-transplant due to complications that may include rejection of transplanted organ, surgical, infectious and metabolic complications.

Acute CMV infection in the post OLT setting is routinely encountered and its clear association with VTE should always be considered when the clinical presentation favors or is suspicious for the same. Based on the data provided above and pathophysiological mechanisms that may be involved, there seems to be a clear association between acute CMV infection and the risk for VTE. Several other factors including hospitalization and immobilization may increase the risk of thromboembolic events in this group of patients. Appropriate prophylaxis for VTE with low molecular weight heparin combined with subcutaneous compression devices should be utilized in these patients. Especially during the time of hospitalization in the post OLT period, providing there are no contraindications. Confirmed diagnosis of VTE should be treated aggressively with appropriate anticoagulation and if contraindicated use of vena caval filters is recommended, to prevent the potentially fatal and dreaded complication of pulmonary embolism. Cytomegalovirus infection if confirmed should be treated appropriately using standard guidelines.

Liver transplantation is severely limited by the availability of donor livers and the financial burden associated with the whole process is enormous. Transplant hepatologists and surgeons should be vigilant in providing care for this special group of individuals, whose clinical needs are complex and require a multi-disciplinary approach in their management. A high degree of suspicion for common and not so common complications like VTE occurring simultaneously with acute CMV infection should be maintained. Appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic measures should be undertaken in a timely manner so as to prevent the loss of a vital and scarce treatment modality. Future studies looking into the incidence and prevalence of VTE in the post OLT patients, their associations with CMV status before transplant and at the time of occurrence of VTE are warranted to better define the risk and their association.

P- Reviewers: Bannasch P, Pallottini V, Yasunobu M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Paran Y, Shalev V, Steinvil A, Justo D, Zimmerman O, Finn T, Berliner S, Zeltser D, Weitzman D, Raz R. Thrombosis following acute cytomegalovirus infection: a community prospective study. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:969-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schimanski S, Linnemann B, Luxembourg B, Seifried E, Jilg W, Lindhoff-Last E, Schambeck CM. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with venous thromboembolism of immunocompetent adults--a case-control study. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:597-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kazory A, Ducloux D, Coaquette A, Manzoni P, Chalopin JM. Cytomegalovirus-associated venous thromboembolism in renal transplant recipients: a report of 7 cases. Transplantation. 2004;77:597-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fridlender ZG, Khamaisi M, Leitersdorf E. Association between cytomegalovirus infection and venous thromboembolism. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chiu B, Viira E, Tucker W, Fong IW. Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus in atherosclerosis of the carotid artery. Circulation. 1997;96:2144-2148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sutherland MR, Raynor CM, Leenknegt H, Wright JF, Pryzdial EL. Coagulation initiated on herpesviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13510-13514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Delbos V, Abgueguen P, Chennebault JM, Fanello S, Pichard E. Acute cytomegalovirus infection and venous thrombosis: role of antiphospholipid antibodies. J Infect. 2007;54:e47-e50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schambeck CM, Hinney K, Gleixner J, Keller F. Venous thromboembolism and associated high plasma factor VIII levels: linked to cytomegalovirus infection? Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:510-511. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Nieto FJ, Sorlie P, Comstock GW, Wu K, Adam E, Melnick JL, Szklo M. Cytomegalovirus infection, lipoprotein(a), and hypercoagulability: an atherogenic link? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1780-1785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Limaye AP, Bakthavatsalam R, Kim HW, Randolph SE, Halldorson JB, Healey PJ, Kuhr CS, Levy AE, Perkins JD, Reyes JD. Impact of cytomegalovirus in organ transplant recipients in the era of antiviral prophylaxis. Transplantation. 2006;81:1645-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |