Published online Nov 27, 2013. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i11.612

Revised: October 21, 2013

Accepted: November 2, 2013

Published online: November 27, 2013

Processing time: 80 Days and 22.6 Hours

Rituximab is recognized as a useful drug for the treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and its use has been extended to such diseases as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, chronic rheumatoid arthritis and ANCA-associated vasculitides. One serious complication associated with its use is the reactivation of hepatitis B virus and the search for methods to prevent this occurrence has resulted in the rapid accumulation of knowledge. In this review, we discuss case analyses from our department and other groups and outline the current knowledge on the topic and the remaining issues.

Core tip: The deleterious effects of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens have been reported and the effect of lamivudine treatment in the prevention of HBV reactivation is also well documented. Once reactivated, HBV may lead to death due to hepatitis. In this review, we discuss the factors of preventive lamivudine treatment (especially in the course of HBV antibody), including to whom and for how long the drug should be given, based on case studies and reports that span rituximab’s debut in 2002 on the Japanese market to June 2013.

- Citation: Tsutsumi Y, Yamamoto Y, Shimono J, Ohhigashi H, Teshima T. Hepatitis B virus reactivation with rituximab-containing regimen. World J Hepatol 2013; 5(11): 612-620

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v5/i11/612.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v5.i11.612

Rituximab, which is a mouse-human chimeric antibody that targets CD20, was introduced to treat B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and has improved outcomes in this patient group[1-3]. Reports, however, indicate that it may be associated with such complications as several serious viral infections and work is currently underway to understand and deal with this problem[4-7]. One such complication is the reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV), an important problem that was sometimes observed with chemotherapy treatments even before the introduction of rituximab[8-12]. The deleterious effects of HBV reactivation in rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens have been reported and the effect of lamivudine treatment in the prevention of HBV reactivation is also well documented[13-17]. Several issues remain, including the optimal timing and the treatment length of preventive lamivudine and the follow-up range of patients who are responsive to this treatment. Once reactivated, HBV may lead to death due to hepatitis in some patients[18-22]. Even in cases where hepatitis has been overcome, HBV reactivation can disrupt the optimal treatment schedule for lymphomas and lead to relapse and shortened survival. In this review, we discuss factors in preventive lamivudine treatment, including to whom lamivudine should be given and for how long, based on case studies and reports that span from rituximab’s debut on the Japanese market in 2002 to June 2013.

Upon HBV infection, HBV-DNA synthesis is initially suppressed by cytokine production by NK and other cells. A subsequent cytotoxic T cell (CTL) reaction occurs due to the CD8-positive T lymphocyte. Because hepatitis is triggered by CTLs, a time lag probably exists between HBV infection and hepatitis’s manifestation[23,24]. Hepatitis that stems from HBV reactivation is thought to progress in a smaller time period than the initial infection because the virus is induced when immunosuppression is engaged under conditions where CTLs are being induced and HBV has been reactivated and has replicated. This system, which leads to accelerated hepatitis progression, might be linked to the number of deaths that occurred despite the administration of such drugs as lamivudine upon HBV reactivation when using chemotherapy or immunosuppressive agents.

We previously reported the occurrence of HBV reactivation following rituximab therapy as well as rituximab-combined chemotherapy treatments. Despite some variations, the prevalence of HBV reactivation is estimated at between 20%-55%[25-28]. However, there are reports of a 3% prevalence rate in HBsAg-negative cases[29]. Reactivation is often associated with the chemotherapy given for lymphomas and is probably influenced by steroids[26,30]. Upon the introduction of rituximab, it was initially debated whether rituximab alone or combined with chemotherapy could induce HBV reactivation and our subsequent study, as well as work by Yang et al[22], reported HBV reactivation after rituximab alone, suggesting that rituximab itself, without chemotherapy, can induce HBV reactivation[14,22]. Although rituximab is more likely to induce HBV reactivation in combination with chemo- or steroid- therapies, since it alone can induce HBV reactivation, caution must be exercised in its use[14]. Debate continues over whether the addition of rituximab to chemotherapy increases the risk of HBV reactivation. Our results involving a survey at a hematology institute in Hokkaido showed that reactivation only developed when rituximab was used. This result is consistent with another study by Yeo et al[31] that suggested that rituximab increases the chance of HBV reactivation more than chemotherapy alone[14,31]. Rituximab is more likely to induce HBV reactivation in combination with chemo- or steroid- therapies, since it alone increases the chance of HBV reactivation.

Reports have identified the risk factors for HBV reactivation and they include being male, a lack of anti-HBs antibodies, HBV-DNA level, presence of lymphomas, anthracycline/steroid use, second/third line anticancer treatment and youth. These risk factors were reviewed by Yeo et al[32], who concluded that being male, young and liver function prior to chemotherapy are associated with risk factors. When rituximab is used, the identified risk factors for HBV reactivation include being male, a lack of anti-HBs antibodies and using rituximab[28,31,32]. Huang et al[33] recently reported that the lack of entecavir administration is the most important factor of HBV reactivation in rituximab-associated therapy. This report concluded that the most important treatment to prevent HBV reactivation was the preventive prophylactic administration of preventive nucleoside analog therapy, not only for HBe antigen-, HBs antigen- and anti-HBc-positive cases but also for anti-HBs-positive cases. A lack of prophylactic nucleoside analog therapy is the most important risk factor of HBV reactivation.

HBV reactivation has been reported in HBs antigen-positive patients after chemotherapy and rituximab plus chemotherapy[8,17,22,34,35]. In these patients, caution is advised to prevent HBV reactivation, with or without rituximab. Such preventive nucleoside analog approaches as lamivudine or entecavir administration are currently recommended and a combination of lamivudine and chemotherapy has been suggested[36-40]. These reports indicate that HBV reactivation during chemotherapy is markedly suppressed in groups given preventive nucleoside analog administration and that chemotherapy can proceed as scheduled. There are few systematic studies on the concomitant usage of lamivudine and rituximab; however, some, including He et al[41], suggest the efficacy of preventive lamivudine[41-44]. Recently, Huang et al[33] also reported the efficacy of the preventive administration of entecavir. Studies using lamivudine to treat HBV hepatitis have reported an annual increase of approximately 15%-20% in HBV lamivudine resistance[45,46], indicating the problem of the emergence of drug-resistant HBV strains during preventive lamivudine administration. Pelizzari et al[47], however, showed that for lamivudine treatment during chemotherapy for hematological malignancies, the frequency of drug resistance may be lower than what was seen in hepatitis B treatment, suggesting that long-term lamivudine treatment might be possible. But the study’s observation period was short and the number of cases was limited. Perhaps resistance was also difficult to acquire because the nucleoside analogs were administered for cases initially negative for HBV-DNA.

Picardi et al[48] reported a high prevalence of HBV genomic mutations after fludarabine-based chemotherapy, arguing that strong immunosuppression might induce HBV resistance to lamivudine. Similar reports exist with combined rituximab chemotherapy, suggesting that adding steroids or fludarabine to rituximab may result in a high frequency of drug resistance[49]. We believe that the relationship of immunosuppression and HBV genomic mutations requires further study because it remains undetermined whether long-term preventive lamivudine treatment combined with strong immunosuppression treatment is possible. Perhaps preventive methods concerning HBV-DNA levels among HBsAg-positive cases will change. In each guideline, for cases that require a year or more of long-term administration of nucleoside analogs against HBV-DNA, switching to entecavir is recommended. This is because in patients with high HBV-DNA levels, using entecavir is desirable based on its relationship to YMDD mutations[50-52]. In referring to the guideline treatments against the chronic hepatitis of HBsAg, entecavir use is desirable when HBV-DNA exceeds 20000 IU/mL and lamivudine use is adequate if HBV-DNA falls under 20000 IU/mL. In addition, in HBV-DNA-positive cases, we must examine the YMDD mutations beforehand. If they are detected, using tenofovir or the combined use of two nucleoside analogs might become necessary[50-52]. (1) The prevention of nucleoside analog approaches was necessary in HBs antigen-positive, anti-HBc-positive and HBV-DNA-positive cases; (2) HBV genomic mutations were observed in the regimens that used fludarabine but it remains unclear whether strong immunosuppression caused the HBV genomic mutations; (3) YMDD mutations are desirable to select the prophylactic administration of nucleoside analogs; and (4) Entecavir use is desirable when HBV-DNA exceeds 20000 IU/mL and lamivudine use is adequate if HBV-DNA falls below 20000 IU/mL.

Anti-HBc-positive cases indicate the occurrence of a prior HBV infection. Some cases fall into the window period or they are anti-HBs and HBs antigen-negative, but anti-HBc and HBV-DNA positives (occult HBV infection)[53] require caution when using chemotherapy with rituximab and anti-cancer agents[29]. Additionally, there are reports of HBV reactivation following chemotherapy in anti-HBs-positive and anti-HBc-positive patients[16,25,30]. Furthermore, Hui et al[29] reported hepatitis that originated from HBV reactivation in anti-HBc-positive and anti-HBs-negative cases, even when HBV-DNA is negative. This shows that in anti-HBc-positive cases, hepatitis can develop from HBV reactivation regardless of the HBV-DNA status. The guidelines recommend strict observation of HBV-DNA levels for these groups, since hepatitis due to HBV reactivation is infrequent and the treatment costs of HBV prevention are high[50-53]. Although HBV reactivation in these patients is infrequent, it may lead to prolonged use of chemotherapy, less chemotherapeutic efficacy against lymphoma, and even death from HBV hepatitis. In particular, the lethality rate is 30%-38% in cases where hepatitis occurs from HBV reactivation[29,54]. When considering cost, however, it is desirable to identify a subgroup of patients within the anti-HBc-positive group that is especially prone to HBV reactivation. Previous analysis showed that the only risk factor of HBV reactivation was without the prevention of a HBV reactivation drug[33]. Therefore, preventive nucleoside analog in all anti-HBc-positive patients is recommended; (1) In anti-HBc-positive, anti-HBs-negative and HBsAg-negative cases, one idea is the strict observation of HBV-DNA levels since hepatitis due to HBV reactivation is infrequent; (2) In these patients, HBV reactivation is infrequent and the lethality rate is 30%-38% in cases where hepatitis occurs from HBV reactivation; and (3) Although HBV reactivation in these patients is infrequent, it is desirable to use a preventive nucleoside analog in all anti-HBc-positive patients because of the lethality rate or HBV reactivation.

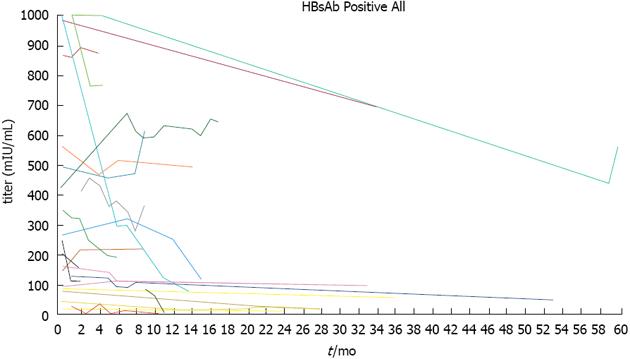

Hepatitis from HBV reactivation has been reported in anti-HBs-positive, anti-HBc-positive and HBsAg-negative cases[16,25,29,30]. Few reports exist of HBV reactivation following rituximab treatment in patients positive for anti-HBs alone, but reactivation may occur, and these patients require careful observation[17,29,55]. Perhaps in these cases, antibody production may have declined with age, only anti-HBs remain and the specific details are unknown. However, since perhaps even anti-HBs-positive cases are due to HBV reactivation, caution is warranted. We previously studied the changes in anti-HBs titers during rituximab chemotherapy[13,20,21]. In these cases, perhaps because the initial antibody titer was relatively low, we observed a linear decrease in the titer in correlation with the amount of rituximab. We also reported a patient in whom anti-HBs and anti-HBc titers decreased, while HBV-DNA increased and HBV reactivation occurred[20,21]. These results show a correlation between anti-HBs antibodies and HBV reactivation and suggest that monitoring their titers can provide important clues about HBV reactivation. Additionally, Onozawa et al[56] reported that hepatitis from HBV reactivation occurs from a decline in HBs antibody titer levels during bone marrow transplantation. Since HBs antibody is a humoral immune response that monitors HBV, a change in the HBs antibody titer could predict hepatitis that occurs from HBV reactivation. In this report, we continued to analyze the titer in an anti-HBs-positive patient who was treated with rituximab alone or rituximab plus chemotherapy between January 2002 and July 2013. The 35 subjects (18 males and 17 females) ranged from 42 to 87 years of age (Table 1) and included 17 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and nine cases of follicular lymphoma. In almost all the patients, the initial treatment consisted of two to six rounds of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, 750 mg/m2, vincristine, 1.4 mg/m2, adriamycine, 50 mg/m2 on day 1, and prednisolone, 60 mg/m2 on days 1-5) that was mainly combined with rituximab or THP-COP (cyclophosphamide, 500 mg/m2, vincristine, 1.0 mg/m2, and pinorubine, 30 mg/m2 on day 1, and prednisolone, 30 mg/m2 on days 1-5). The clinical course of the anti-HBs antibody is shown in Figure 1. In five of 35 cases, the antibody titer slightly increased, and in three cases, it declined. In nine of 45 cases, the antibody titer was the same, and in 21 of 35, it declined after rituximab and chemotherapy. In six of nine cases with anti-HBs titers > 1000 mIU/mL at the time of the initial treatment, the titer did not fall below 1000 mIU/mL. However, in one particular case, the initial titer was > 1000 mIU/mL, and the anti-HBs titer fell to 71.1 mIU/mL after three rounds of treatment. This demonstrates that even in patients with initial anti-HBs titers > 1000 mIU/mL, HBV reactivation can nonetheless occur, indicating that caution must be exercised. Among these 35 patients, the antibody titers in ten were the same or elevated compared with the titer before the treatment. In 24 patients whose anti-HBs titer levels finally decreased, 16 patients had initial titers < 300 mIU/mL (16/18 patients of < 300 mIU/mL), and 11 had initial titers < 100 mIU/mL (11/12 patients of < 100 mIU/mL), demonstrating the need for preventive nucleoside analog administration. Six patients with anti-HBs titers > 1000 mIU/mL did not show a titer decrease. Although these cases are not completely accurate since we cannot measure titers above 1000 mIU/mL, in these patients, the titers probably did not drop below 1000 mIU/mL. Pei et al[57] reported anti-HBs antibody titers after rituximab therapy and concluded that the risks of HBV reactivation are the reduction of anti-HBs titers, especially low pretreatment anti-HBs titers and the loss of anti-HBs. These results on titer changes might provide an index for preventive lamivudine or entecavir administration in patients who are only anti-HBs-positive. Consistent with our results, Westhoff et al[16] reported HBV reactivation in a patient with an anti-HBs titer of approximately 868 mIU/mL, demonstrating the possibility of HB ion may occur. Even when anti-HBs-positive cases are due to HBV reactivation, caution is warranted; (2) Anti-HBs titer decreased in correlation with the amount of rituximab. Anti-HBs and anti-HBc titers decreased, while HBV-DNA increased and HBV reactivation occurred. The reduction of anti-HBs titers, especially low pretreatment anti-HBs titers, and the loss of anti-HBs are risk of HBV reactivation; (3) For anti-HBs titers > 1000 mIU/mL at the time of initial treatment, the titers of most patients did not fall below 1000 mIU/mL. In almost all cases where the initial anti-HBs titer was < 300, titers decreased; and (4) Monitoring HBV-DNA and anti-HBs titers is useful to prevent HBV reactivation.

| Characteristics of anti-HBs Ab positive patients | |

| Age (yr) | 67 (42-87) |

| Males/Females | 18/17 |

| Disease | |

| DLB | 17 |

| FL | 9 |

| MCL | 1 |

| MALT | 3 |

| Burkitt lymphoma | 1 |

| EBV associated LPD | 1 |

| WM | 1 |

| CLL | 2 |

| Stage | |

| I | 3 |

| II | 3 |

| III | 7 |

| IV | 21 |

| Chemotherapy | |

| R-CHOP | 10 |

| R-THP-COP | 20 |

| R+VP16 | 1 |

| R+MVP | 1 |

| R+TEOP | 1 |

| R+bendamustine | 1 |

| R | 2 |

| R-Course | 10 (1-30) |

As mentioned above, HBe and HBs antigen-positive patients can be treated with preventive nucleoside analogs. In HBs antigen-negative and anti-HBc-positive patients, the frequency of HBV reactivation is not high; however, since it can result in death from hepatitis, preventive nucleoside analog should be considered for them as well. We previously reported the relatively high frequency of HBV reactivation in anti-HBc-positive and HBsAg-negative patients with rituximab and bendamustine treatment[58]. These results also support the preventive nucleoside analog for HBV reactivation in the new agents that have cytotoxic and immunosuppressive reactions.

On the other hand, in HBs antigen-negative and anti-HBs-positive patients, preventive nucleoside analog treatment may be considered when the anti-HBs titer is < 300 mIU/mL, especially when the titers are < 100 mIU/mL. In cases where the titer is between 300 and 1000 mIU/mL or higher, the titer levels should be closely examined, and when the titer drops below 300 mIU/mL, HBV-DNA monitoring or preventive nucleoside analog treatment should be performed. Periodic examination of HBV-DNA is also recommended to predict HBV reactivation[59,60]. The emergence of antibodies may also be slow in cases where a mutation occurred and thus HBV-DNA monitoring is essential[59]. However, in patients where only HBV-DNA monitoring was performed, the frequency of HBV reactivation was higher than those who were treated with preventive lamivudine, demonstrating the importance of identifying a subgroup of patients for which preventive lamivudine is recommended[37]. In evaluating methods to predict HBV reactivation, HBV-DNA monitoring alone is insufficient and other pieces of information, such as shifts in the anti-HB titer levels (before and during the rituximab treatment), should be utilized to assist the early detection of HBV reactivation. Preventive nucleoside analog against HBV is currently recommended for 4-6 mo after chemotherapy completion[46,50,52,61]. However, reports of HBV reactivation 4 to 6 mo after chemotherapy[62-65] suggest that this number should be revised. The current 6 mo value probably reflects our knowledge about the changes in B-cell numbers[60,64,66-68]. The 2007 guidelines by Lok et al[50] are more specific than past guidelines and include a recommendation to extend the period of preventive lamivudine treatment, depending on HBV-DNA monitoring results. Some research reported a delayed onset of the HBV reactivation with rituximab therapy[69-71]. We also observed a case in which HBV reactivation was detected 4 years after chemotherapy and preventive lamivudine administration had been completed. The patient was a precore mutant case positive for HBe antibody, HBs antigen, and negative for HBe antigen. Due to declining blood cell counts, lamivudine therapy had been terminated and the patient was under observation for progression since entecavir had not yet been approved for HBV treatment in Japan. After initially administering lamivudine in 2002 and terminating it a month after completion of the treatment (2003), HBV-DNA was detected only sporadically in the patient. In 2003, HBs antibodies appeared with a natural progression and HBV-DNA disappeared in 2004. However, HBs antibody could not be detected, and from the latter half of 2004 to the beginning of 2006, detection was sporadic. From 2007, HBV-DNA was positive in every reading and in 2008, the individual died after being hospitalized for hepatitis from HBV reactivation. We believe that for anti-HBs-negative HBe or HBs antigen-positive patients, preventive lamivudine should be included when initiating treatment and continued indefinitely. On the other hand, anti-HBs-positive HBV-DNA became negative in this patient, suggesting that in anti-HBs-positive patients, nucleoside analog treatment should be continued until the anti-HBs titer returns to the pre-treatment level. We believe that 6 mo of preventive lamivudine treatment is too short; its length should be based on the recovery of the immune system, as judged by such criteria as anti-HBs levels. Long-term administration of such drugs as lamivudine or entecavir is problematic in terms of cost and cases that require long-term preventive administration must be clarified in the future by longitudinal surveys. In Japan, lamivudine is the only drug currently approved for preventive administration. Entecavir is also used to treat HBV infection; however, it is currently not allowed for preventive administration. For treatment regimens, 100 mg of lamivudine and 0.5 mg of entecavir are used. However, it is recommended that entecavir be increased to 1 mg to counter lamivudine resistance[50-52]. Telbivudine may also be used in the prophylaxis of HBV reactivation. Compared to lamivudine and telbivudine, entecavir is less likely to induce drug resistance in HBV, which has a treatment advantage and the preventive administration of HBV reactivation[65]. For this reason, entecavir administration is recommended for cases in which preventive administration against HBV will last 12 mo or more[50,52]. Additional effective drugs that combat HBV include 10 mg of adefovir, 600 mg of telbivudine, and 200 mg of tenofovir. With respect to lamivudine resistance, some recommend combining entecavir, adefovir or tenofovir with lamivudine[52], and others recommend switching[51]. However, it has also been reported that for lamivudine-resistant HBV strains, switching to adefovir alone quickly produces resistance. Thus, it may be desirable to use adefovir in conjunction with lamivudine[72]. Tenofovir is especially effective against lamivudine- and adefovir-resistant HBV and can be used to treat lamivudine-resistant HBV[45,60,73-75]. Also, using HBV vaccines is recommended for HBV-seronegative cases during the use of immunosuppressive or anti-cancer agents[52]. However, as mentioned above, just as anti-HBs decline and disappear when using rituximab, antibodies might not be produced after the pre-administration of a vaccine and the vaccine must be administered after completion of the treatment. On the other hand, cases may also exist in which hepatitis arising from HBV reactivation cannot be suppressed by a vaccine[55]. Perhaps HBV reactivation cannot be prevented solely by a vaccine. (1) Preventive nucleoside analog treatment may be considered when the anti-HBs titer is < 300 mIU/mL, especially when the titers are < 100 mIU/mL. For other cases, the titer levels should be closely examined, and when they drop below 300 mIU/mL, HBV-DNA monitoring or preventive nucleoside analog treatment should be performed. Periodical examination of HBV-DNA is also recommended to predict HBV reactivation; (2) Although preventive nucleoside analog against HBV is currently recommended for 4-6 mo after chemotherapy completion, delayed onset of the HBV reactivation was observed. The length of the treatment should be based on the recovery of the immune system, as judged by such criteria as anti-HBs levels; (3) Lamivudine and entecavir are used for the prevention of HBV reactivation in Japan. Telbivudine may also be used in the prophylactic administration of HBV reactivation. Compared to lamivudine and telbivudine, entecavir is less likely to induce drug resistance in HBV, which has a treatment advantage, and the preventive administration of HBV reactivation; and (4) Tenofovir is especially effective against lamivudine- and adefovir-resistant HBV and can be used to treat lamivudine-resistant HBV.

Chemotherapy-induced HBV reactivation is thought to be caused by HBV replication in hepatocytes due to immunosuppression by anti-cancer agents, followed by a decline in the immunosuppressive effect, triggering the immune system to attack HBV-infected hepatocytes[30]. Decreased antibody titer levels resulting from decreased numbers of B-cells may be one factor that causes rituximab-induced HBV proliferation. Additionally, rituximab can indirectly alter the T-cell population in the body and stimulate HBV replication, and during immune reconstitution, the targeting of HBV may be intensified[76]. As reported by Umemura et al[35], chemotherapy-induced HBV reactivation results in lower survival rates than acute HBV hepatitis and thus prevention of HBV reactivation is essential. However, the screening of HBV serology is not performed routinely (36.6%). Some HBV reactivation was developed by the lack of HBV screening[77]. We hope that in the future, HBV screening will be performed routinely so that we can better understand the effect of rituximab on the immune system as well as the mechanism of HBV reactivation for improved treatment of malignant lymphomas.

P- Reviewers: Mihm S, Ribera JM, Sobhonslidsuk A S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Yan JL

| 1. | Maloney DG, Liles TM, Czerwinski DK, Waldichuk C, Rosenberg J, Grillo-Lopez A, Levy R. Phase I clinical trial using escalating single-dose infusion of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (IDEC-C2B8) in patients with recurrent B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1994;84:2457-2466. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Bodkin D, Schilder RJ, Neidhart JA, Janakiraman N, Foon KA, Liles TM, Dallaire BK. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1997;90:2188-2195. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, Bodkin DJ, White CA, Liles TM, Royston I, Varns C, Rosenberg J, Levy R. IDEC-C2B8: results of a phase I multiple-dose trial in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3266-3274. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bermúdez A, Marco F, Conde E, Mazo E, Recio M, Zubizarreta A. Fatal visceral varicella-zoster infection following rituximab and chemotherapy treatment in a patient with follicular lymphoma. Haematologica. 2000;85:894-895. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sharma VR, Fleming DR, Slone SP. Pure red cell aplasia due to parvovirus B19 in a patient treated with rituximab. Blood. 2000;96:1184-1186. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Suzan F, Ammor M, Ribrag V. Fatal reactivation of cytomegalovirus infection after use of rituximab for a post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goldberg SL, Pecora AL, Alter RS, Kroll MS, Rowley SD, Waintraub SE, Imrit K, Preti RA. Unusual viral infections (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and cytomegalovirus disease) after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous blood stem cell rescue and peritransplantation rituximab. Blood. 2002;99:1486-1488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Galbraith RM, Eddleston AL, Williams R, Zuckerman AJ. Fulminant hepatic failure in leukaemia and choriocarcinoma related to withdrawal of cytotoxic drug therapy. Lancet. 1975;2:528-530. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hoofnagle JH, Dusheiko GM, Schafer DF, Jones EA, Micetich KC, Young RC, Costa J. Reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection by cancer chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:447-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Thung SN, Gerber MA, Klion F, Gilbert H. Massive hepatic necrosis after chemotherapy withdrawal in a hepatitis B virus carrier. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1313-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lau JY, Lai CL, Lin HJ, Lok AS, Liang RH, Wu PC, Chan TK, Todd D. Fatal reactivation of chronic hepatitis B virus infection following withdrawal of chemotherapy in lymphoma patients. Q J Med. 1989;73:911-917. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Liang RH, Lok AS, Lai CL, Chan TK, Todd D, Chiu EK. Hepatitis B infection in patients with lymphomas. Hematol Oncol. 1990;8:261-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tsutsumi Y, Kanamori H, Mori A, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M, Masauzi N. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus with rituximab. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:599-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tsutsumi Y, Shigematsu A, Hashino S, Tanaka J, Chiba K, Masauzi N, Kobayashi H, Kurosawa M, Iwasaki H, Morioka M. Analysis of reactivation of hepatitis B virus in the treatment of B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Hokkaido. Ann Hematol. 2009;88:375-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Skrabs C, Müller C, Agis H, Mannhalter C, Jäger U. Treatment of HBV-carrying lymphoma patients with Rituximab and CHOP: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Leukemia. 2002;16:1884-1886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Westhoff TH, Jochimsen F, Schmittel A, Stoffler-Meilicke M, Schafer JH, Zidek W, Gerlich WH, Thiel E. Fatal hepatitis B virus reactivation by an escape mutant following rituximab therapy. Blood. 2003;102:1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dervite I, Hober D, Morel P. Acute hepatitis B in a patient with antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen who was receiving rituximab. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:68-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ng HJ, Lim LC. Fulminant hepatitis B virus reactivation with concomitant listeriosis after fludarabine and rituximab therapy: case report. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:549-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jäeger G, Neumeister P, Brezinschek R, Höfler G, Quehenberger F, Linkesch W, Sill H. Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) as consolidation of first-line CHOP chemotherapy in patients with follicular lymphoma: a phase II study. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tsutsumi Y, Kawamura T, Saitoh S, Yamada M, Obara S, Miura T, Kanamori H, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in a case of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and rituximab: necessity of prophylaxis for hepatitis B virus reactivation in rituximab therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:627-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tsutsumi Y, Tanaka J, Kawamura T, Miura T, Kanamori H, Obara S, Asaka M, Imamura M, Masauzi N. Possible efficacy of lamivudine treatment to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation due to rituximab therapy in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:58-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yang SH, Kuo SH. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus during rituximab treatment of a patient with follicular lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:325-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Guidotti LG, Rochford R, Chung J, Shapiro M, Purcell R, Chisari FV. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science. 1999;284:825-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 949] [Cited by in RCA: 914] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Webster GJ, Reignat S, Maini MK, Whalley SA, Ogg GS, King A, Brown D, Amlot PL, Williams R, Vergani D. Incubation phase of acute hepatitis B in man: dynamic of cellular immune mechanisms. Hepatology. 2000;32:1117-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, Wong KL, Chan TK, Todd D. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:182-188. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Nakamura Y, Motokura T, Fujita A, Yamashita T, Ogata E. Severe hepatitis related to chemotherapy in hepatitis B virus carriers with hematologic malignancies. Survey in Japan, 1987-1991. Cancer. 1996;78:2210-2215. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kumagai K, Takagi T, Nakamura S, Sawada U, Kura Y, Kodama F, Shimano S, Kudoh I, Nakamura H, Sawada K. Hepatitis B virus carriers in the treatment of malignant lymphoma: an epidemiological study in Japan. Ann Oncol. 1997;8 Suppl 1:107-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, Hui P, Leung NW, Zee B, Johnson PJ. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62:299-307. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Hui CK, Cheung WW, Zhang HY, Au WY, Yueng YH, Leung AY, Leung N, Luk JM, Lie AK, Kwong YL. Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg-negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Vento S, Cainelli F, Longhi MS. Reactivation of replication of hepatitis B and C viruses after immunosuppressive therapy: an unresolved issue. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:333-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, Lam WY, Mo FK, Chu MT, Chan HL, Hui EP, Lei KI, Mok TS. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:605-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yeo W, Zee B, Zhong S, Chan PK, Wong WL, Ho WM, Lam KC, Johnson PJ. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associating with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1306-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Huang YH, Hsiao LT, Hong YC, Chiou TJ, Yu YB, Gau JP, Liu CY, Yang MH, Tzeng CH, Lee PC. Randomized controlled trial of entecavir prophylaxis for rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2765-2772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sera T, Hiasa Y, Michitaka K, Konishi I, Matsuura K, Tokumoto Y, Matsuura B, Kajiwara T, Masumoto T, Horiike N. Anti-HBs-positive liver failure due to hepatitis B virus reactivation induced by rituximab. Intern Med. 2006;45:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Umemura T, Kiyosawa K. Fatal HBV reactivation in a subject with anti-HBs and anti-HBc. Intern Med. 2006;45:747-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Loomba R, Rowley A, Wesley R, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH, Pucino F, Csako G. Systematic review: the effect of preventive lamivudine on hepatitis B reactivation during chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:519-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lau GK, Yiu HH, Fong DY, Cheng HC, Au WY, Lai LS, Cheung M, Zhang HY, Lie A, Ngan R. Early is superior to deferred preemptive lamivudine therapy for hepatitis B patients undergoing chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1742-1749. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Silvestri F, Ermacora A, Sperotto A, Patriarca F, Zaja F, Damiani D, Fanin R, Baccarani M. Lamivudine allows completion of chemotherapy in lymphoma patients with hepatitis B reactivation. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:394-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shibolet O, Ilan Y, Gillis S, Hubert A, Shouval D, Safadi R. Lamivudine therapy for prevention of immunosuppressive-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B surface antigen carriers. Blood. 2002;100:391-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yeo W, Ho WM, Hui P, Chan PK, Lam KC, Lee JJ, Johnson PJ. Use of lamivudine to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation during chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;88:209-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | He YF, Li YH, Wang FH, Jiang WQ, Xu RH, Sun XF, Xia ZJ, Huang HQ, Lin TY, Zhang L. The effectiveness of lamivudine in preventing hepatitis B viral reactivation in rituximab-containing regimen for lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:481-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mimidis K, Tsatalas C, Margaritis D, Martinis G, Spanoudakis E, Kotsiou S, Kartalis G, Bourikas G. Efficacy of Lamivudine in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving chemotherapy and precore mutant chronic active hepatitis B. Acta Haematol. 2002;107:49-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Hamaki T, Kami M, Kusumi E, Ueyama J, Miyakoshi S, Morinaga S, Mutou Y. Prophylaxis of hepatitis B reactivation using lamivudine in a patient receiving rituximab. Am J Hematol. 2001;68:292-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kami M, Hamaki T, Murashige N, Kishi Y, Kusumi E, Yuji K, Miyakoshi S, Ueyama J, Morinaga S, Mutou Y. Safety of rituximab in lymphoma patients with hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection. Hematol J. 2003;4:159-162. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update of recommendations. Hepatology. 2004;39:857-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;34:1225-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Pelizzari AM, Motta M, Cariani E, Turconi P, Borlenghi E, Rossi G. Frequency of hepatitis B virus mutant in asymptomatic hepatitis B virus carriers receiving prophylactic lamivudine during chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. Hematol J. 2004;5:325-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Picardi M, Pane F, Quintarelli C, De Renzo A, Del Giudice A, De Divitiis B, Persico M, Ciancia R, Salvatore F, Rotoli B. Hepatitis B virus reactivation after fludarabine-based regimens for indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: high prevalence of acquired viral genomic mutations. Haematologica. 2003;88:1296-1303. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Miyagawa M, Minami M, Fujii K, Sendo R, Mori K, Shimizu D, Nakajima T, Yasui K, Itoh Y, Taniwaki M. Molecular characterization of a variant virus that caused de novo hepatitis B without elevation of hepatitis B surface antigen after chemotherapy with rituximab. J Med Virol. 2008;80:2069-2078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1794] [Cited by in RCA: 1778] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Liaw YF, Leung N, Guan R, Lau GK, Merican I, McCaughan G, Gane E, Kao JH, Omata M. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2005 update. Liver Int. 2005;25:472-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in RCA: 1155] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Hu KQ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and its clinical implications. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:243-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Yeo W, Lam KC, Zee B, Chan PS, Mo FK, Ho WM, Wong WL, Leung TW, Chan AT, Ma B. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing systemic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1661-1666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Awerkiew S, Däumer M, Reiser M, Wend UC, Pfister H, Kaiser R, Willems WR, Gerlich WH. Reactivation of an occult hepatitis B virus escape mutant in an anti-HBs positive, anti-HBc negative lymphoma patient. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:83-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Onozawa M, Hashino S, Izumiyama K, Kahata K, Chuma M, Mori A, Kondo T, Toyoshima N, Ota S, Kobayashi S. Progressive disappearance of anti-hepatitis B surface antigen antibody and reverse seroconversion after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with previous hepatitis B virus infection. Transplantation. 2005;79:616-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Pei SN, Ma MC, Wang MC, Kuo CY, Rau KM, Su CY, Chen CH. Analysis of hepatitis B surface antibody titers in B cell lymphoma patients after rituximab therapy. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1007-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Tsutsumi Y, Ogasawara R, Miyashita N, Tanaka J, Asaka M, Imamura M. HBV reactivation in malignant lymphoma patients treated with rituximab and bendamustine. Int J Hematol. 2012;95:588-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Allain JP. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. Transfus Clin Biol. 2004;11:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Liang R. How I treat and monitor viral hepatitis B infection in patients receiving intensive immunosuppressive therapies or undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantatio. Blood. 2009;113:3147-3153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Christensen PB, Clausen MR, Krarup H, Laursen AL, Schlichting P, Weis N. Treatment for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection - Danish national guidelines 2011. Dan Med J. 2012;59:C4465. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Gossmann J, Scheuermann EH, Kachel HG, Geiger H, Hauser IA. Reactivation of hepatitis B two years after rituximab therapy in a renal transplant patient with recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a note of caution. Clin Transplant. 2009;23:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Reff ME, Carner K, Chambers KS, Chinn PC, Leonard JE, Raab R, Newman RA, Hanna N, Anderson DR. Depletion of B cells in vivo by a chimeric mouse human monoclonal antibody to CD20. Blood. 1994;83:435-445. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:209-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Dusheiko G, Archimandritis AJ. Therapeutic strategies in the management of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:167-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | McLaughlin P, Grillo-López AJ, Link BK, Levy R, Czuczman MS, Williams ME, Heyman MR, Bence-Bruckler I, White CA, Cabanillas F. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2825-2833. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Tobinai K, Kobayashi Y, Narabayashi M, Ogura M, Kagami Y, Morishima Y, Ohtsu T, Igarashi T, Sasaki Y, Kinoshita T. Feasibility and pharmacokinetic study of a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (IDEC-C2B8, rituximab) in relapsed B-cell lymphoma. The IDEC-C2B8 Study Group. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:527-534. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Igarashi T, Ohtsu T, Fujii H, Sasaki Y, Morishima Y, Ogura M, Kagami Y, Kinoshita T, Kasai M, Kiyama Y. Re-treatment of relapsed indolent B-cell lymphoma with rituximab. Int J Hematol. 2001;73:213-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Dai MS, Chao TY, Kao WY, Shyu RY, Liu TM. Delayed hepatitis B virus reactivation after cessation of preemptive lamivudine in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab plus CHOP. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:769-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Garcia-Rodriguez MJ, Canales MA, Hernandez-Maraver D, Hernandez-Navarro F. Late reactivation of resolved hepatitis B virus infection: an increasing complication post rituximab-based regimens treatment? Am J Hematol. 2008;83:673-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Perceau G, Diris N, Estines O, Derancourt C, Lévy S, Bernard P. Late lethal hepatitis B virus reactivation after rituximab treatment of low-grade cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1053-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Fung SK, Andreone P, Han SH, Rajender Reddy K, Regev A, Keeffe EB, Hussain M, Cursaro C, Richtmyer P, Marrero JA. Adefovir-resistant hepatitis B can be associated with viral rebound and hepatic decompensation. J Hepatol. 2005;43:937-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Peters MG, Hann Hw Hw, Martin P, Heathcote EJ, Buggisch P, Rubin R, Bourliere M, Kowdley K, Trepo C, Gray Df Df. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:91-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Pérez-Roldán F, González-Carro P, Villafáñez-García MC. Adefovir dipivoxil for chemotherapy-induced activation of hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:310-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Tillmann HL, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP. Treatment of hepatitis B in special patient groups: hemodialysis, heart and renal transplant, fulminant hepatitis, hepatitis B virus reactivation. J Hepatol. 2003;39 Suppl 1:S206-S211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Vigna-Perez M, Hernández-Castro B, Paredes-Saharopulos O, Portales-Pérez D, Baranda L, Abud-Mendoza C, González-Amaro R. Clinical and immunological effects of Rituximab in patients with lupus nephritis refractory to conventional therapy: a pilot study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Méndez-Navarro J, Corey KE, Zheng H, Barlow LL, Jang JY, Lin W, Zhao H, Shao RX, McAfee SL, Chung RT. Hepatitis B screening, prophylaxis and re-activation in the era of rituximab-based chemotherapy. Liver Int. 2011;31:330-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |