Published online Dec 27, 2012. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i12.415

Revised: November 7, 2011

Accepted: November 14, 2012

Published online: December 27, 2012

Resection of liver metastases from gynaecological tumours is uncommon. Endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS) are low incidence gynecological tumours which can originate in previous sites of endometriosis or following metaplasia of the pelvic peritoneal wall, and which are exceptionally associated with liver metastasis. We present a 68-year-old woman with a ESS and metachronic liver metastasis treated by liver resection. There is very little literature on clinical management about liver metastasis from ESS, but extrapolating the data obtained with liver metastasis from sarcomas and uterine tumours, we should recommend resection as this is considered a resectable extrauterine metastasis. In cases with more sites of extrauterine disease, liver resection should also be performed if the other sites are resectable.

- Citation: Ramia JM, De la Plaza R, Garcia I, Perna C, Veguillas P, García-Parreño J. Liver metastasis of endometrial stromal sarcoma. World J Hepatol 2012; 4(12): 415-418

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v4/i12/415.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v4.i12.415

Resection of liver metastases (LM) caused by non-colorectal, non-endocrine tumours has progressed from being an exceptional indication to being admitted as the treatment of choice for certain types of neoplasias[1]. Resection of LM from gynaecological tumours is uncommon[1,2]. Endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS) are low incidence tumours which can originate in previous sites of endometriosis or following metaplasia of the pelvic peritoneal wall, and which are exceptionally associated with liver metastasis[2-4]. The reported cases of resection of ESS LM are very rare[2].

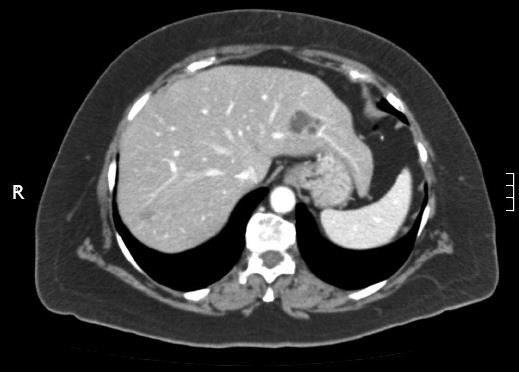

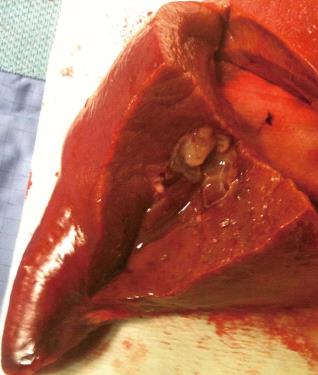

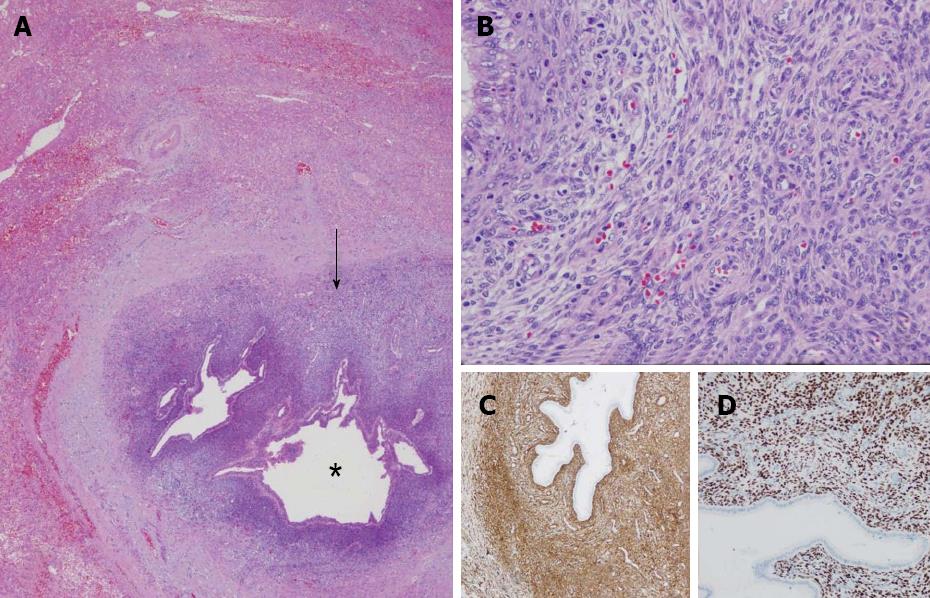

A 68-year-old woman, with a history of hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy because of multiple myomas performed in a hospital in France in 1981. In 1996, the patient was operated in our hospital because of multiple peritoneal implants diagnosed as stage 4B solid-cystic endometrial stroma affecting the peritoneal wall. The patient received post-operative chemotherapy (doxorubicin, iphosphamide and docetaxel). In 2003, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) follow-up detected a 3-cm nodule on the jejunal loop and a 10 cm. Mass which involved the sigmoid colon, for which sigmoidectomy and intestinal resection were performed; ESS metastasis was also diagnosed. From 2003 to present the patient has been treated with letrozole; periodic radiological follow-up was performed. On the last abdominal CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed (June 2010) we observed a 26-mm lesion located in the left lateral area of the liver with poorly defined borders, solid and cystic areas, with heterogeneous contrast uptake (Figure 1). In addition, we observed two previously known hemangiomas in the right liver lobe. There were no radiological data on intra-abdominal recurrence. Positron emission tomography (PET) was performed which did not reveal uptake in the lesion described. Given the onset of a new liver lesion with malignant appearance, in spite of the negativity of PET, we decided to operate and perform a left lateral sectionectomy via subcostal laparotomy. We previously assessed the abdominal cavity confirming that there were no other sites of tumour recurrence. Post-operative clinical course was normal and the patient was discharged on day 3. Macroscopically, the lesion was located 2.5 cm from the surgical margin and presented a cystic appearance with a solid area of yellowish colour and solid appearance (Figure 2). Microscopically, we observed in the liver parenchyma, with a predominantly bile periductal pattern, multiple nodules from tumour proliferation with a mesenchymal appearance similar to the endometrial stroma, with cells from ovoid or elongated nuclei which presented slight atypical cytology. The mitotic index was 8 mitosis figures in 10 enlarged fields (Figure 3). We observed marked immunostaining to oestrogen and progesterone receptors, alpha-actin and CD10, and negativity to desmin and c-kit. All these findings were highly suggestive with LM from a low-grade ESS (Figure 3), and very similar to those found in the two previous metastases. Treatment was started with megestrol acetate but this had to be discontinued because a deep vein thrombosis occurred. During 6 mo follow-up there were no signs of recurrence.

Uterine sarcomas comprise less than 1% of gynaecological cancers and 2% to 5% of all uterine cancers[4,5]. There are various subtypes of uterine sarcoma, including ESS which are sarcomas arising in the endometrial stroma; they are usually low-grade when present in pre-menopausal patients and high-grade in menopausal patients[4,5]. Cases of ESS account for 10%-15% of all uterine sarcomas and 0.2% of total uterine neoplasias. They are made up of cells similar to the endometrial stroma in their proliferative phase, and have the potential to multiply and metastasise[4,5]. There are different macroscopic appearances of the ESS: single nodule, solid-cystic mass, poorly differentiated lesion or multilocular cystic lesions[4]. Recurrence of ESS despite radical surgery is commonplace and occurs in 36% to 56% of patients with early tumours[4,5]. Indolent growth of recurrences leads to performing repeat surgery and repetitive cytoreduction surgery[4].

The existence of extrauterine disease in ESS occurs in 45% of patients but very rarely in the liver[6]. The number of ESS LM published is exceptionally low; during an intense literature search we only found one other case of resection[2]. Resection of metastasis at a localised distance from the lung or heart is accepted as valid treatment[5], but because of the reduced number of patients with ESS LM there is no scientific validation of the therapy to be used. The cancer clinical practice guide of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network - Version 1.2011 considers that the treatment of choice for isolated disseminated disease from uterine sarcomas is surgical resection with post-operative hormone therapy as we performed in our case[7].

The resection of LM from gynaecological tumours is still rare. The larger multicentre series for non-colorectal, non-endocrine LM includes 43 patients with LM from uterine tumours without specifying the histological lineage, obtaining a 5-year survival rate of 35 % with a median of 32 mo. In the same series, patients with LM from sarcoma from different sites had 5-year survival of 31% with a median of 32 mo[1]. In a series on 66 cases of LM from sarcoma from different sites, 3 were localised in the uterus without specifying the histological lineage[8]. In this series, in addition, it is also stated that sarcoma LM are not usually sensitive to chemotherapy or chemoembolisation, for which reason surgery with a free margin should be considered the best therapeutic option[8].

ESS may occur in extrauterine locations in the absence of a primary lesion which makes diagnosis markedly difficult[2,3]. Extrauterine ESS originate in previous sites of endometriosis or following metaplasia of the pelvic peritoneal wall[2,3]. Therefore, in the event of a liver lesion with ESS histology with no primary uterine lesion we should make a distinction between malignant liver endometriosis, liver primary extrauterine ESS, or undiagnosed liver metastasis from an ESS[2]. For our patient, the previous history made the diagnosis of ESS LM easier.

The number of published cases of liver endometriosis is also very low as there are only 12 cases published to 2009, with a malignancy rate of 25%[9,10]. The implantation mechanism of endometriosis in the liver is unknown[2,10], the proximity of liver endometriosis communicated to the falciform ligament suggests that the most probable route is vascular through the falciform ligament vessels or the umbilical vein[2,10].

The CT image of ESS LM does not have specific characteristics. For our patient, it was a solid-cystic mass just as the primary ESS-an uncommon fact in LM caused by tumours in other organs. This finding, in patients with no previous history of ESS, may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of malignant or complicated cystic tumour[2,9,10]. The PET has shown a sensitivity of 80% to detect extrapelvic metastasis of uterine sarcomas[11], but the experience for ESS is low. The PET was negative in our patient.

The prognosis of ESS is correlated with the mitotic index, the absence of invasion of the myometrium and the presence of extrauterine disease[2,4,6]. Overall survival at 5 years for the ESS is 65%, but it decreases to 32% in those with extrauterine disease. No data are available on survival following resection of ESS LM because of its exceptional nature.

In conclusion, ESS LM are exceptionally rare. There is very little literature on clinical management but we believe that by extrapolating the data obtained with LM from sarcomas and uterine tumours and following the recommendations of the NCCN clinical guide we should recommend resection as this is considered a resectable extrauterine metastasis. In cases with more sites of extrauterine disease, resection of LM should also be performed if the other sites are resectable.

Peer reviewers: Luca Viganò, MD, Department of HPB and Digestive Surgery, Ospedale Mauriziano Umberto I, Largo Turati 62, 10128 Torino, Italy; Dr. Drazen B Zimonjic, Department of Laboratory of Experimental Carcinogenesis, National Cancer Institute, 37 Convent Dr., MSC 4262, Building 37, Room 4128C, Bethesda, MD 20892-4262, United States

S- Editor Xiong L L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Adam R, Chiche L, Aloia T, Elias D, Salmon R, Rivoire M, Jaeck D, Saric J, Le Treut YP, Belghiti J. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases: analysis of 1,452 patients and development of a prognostic model. Ann Surg. 2006;244:524-535. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Khan AW, Craig M, Jarmulowicz M, Davidson BR. Liver tumours due to endometriosis and endometrial stromal sarcoma. HPB (Oxford). 2002;4:43-45. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Cho HY, Kim MK, Cho SJ, Bae JW, Kim I. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the sigmoid colon arising in endometriosis: a case report with a review of literatures. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:412-414. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ashraf-Ganjoei T, Behtash N, Shariat M, Mosavi A. Low grade endometrial stromal sarcoma of uterine corpus, a clinico-pathological and survey study in 14 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:50. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Amant F, Coosemans A, Debiec-Rychter M, Timmerman D, Vergote I. Clinical management of uterine sarcomas. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1188-1198. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Thomas MB, Keeney GL, Podratz KC, Dowdy SC. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: treatment and patterns of recurrence. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:253-256. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Available from: http: //www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/uterine.pdf. |

| 8. | Pawlik TM, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Pollock RE, Ellis LM, Curley SA. Results of a single-center experience with resection and ablation for sarcoma metastatic to the liver. Arch Surg. 2006;141:537-543; discussion 543-544. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Goldsmith PJ, Ahmad N, Dasgupta D, Campbell J, Guthrie JA, Lodge JP. Case hepatic endometriosis: a continuing diagnostic dilemma. HPB Surg. 2009;2009:407206. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sánchez-Pérez B, Santoyo-Santoyo J, Suárez-Muñoz MA, Fernández-Aguilar JL, Aranda-Narváez JM, González-Sánchez A, de la Fuente-Perucho A. [Hepatic cystic endometriosis with malignant transformation]. Cir Esp. 2006;79:310-312. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sung PL, Chen YJ, Liu RS, Shieh HJ, Wang PH, Yen MS, Wen KC, Shen SH, Lai CR, Yuan CC. Whole-body positron emission tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose is an effective method to detect extra-pelvic recurrence in uterine sarcomas. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29:246-251. [PubMed] |