Published online Dec 27, 2012. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i12.399

Revised: November 4, 2011

Accepted: November 14, 2012

Published online: December 27, 2012

Estrium Whey is an alternative nutritional support therapy for women. It’s enhanced with specific nutrients including phytoestrogens, folate, antioxidants and fiber to support healthy estrogen detoxification and hormone balance. We describe the first case of hepatotoxicity due to Estrium Whey in a 51-year old female with metastatic breast cancer with clinical, laboratory and histopathological changes.

- Citation: Velasco MJ, Molina J. Estrium Whey induced hepatitis in a patient with metastatic breast cancer: Case report. World J Hepatol 2012; 4(12): 399-401

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v4/i12/399.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v4.i12.399

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity is an important cause of hepatocellular injury and hepatic necrosis may range from asymptomatic elevations in transaminases to fulminant hepatic failure and death. The majorities of adverse liver reactions are idiosyncratic, and occur in most instances 5-90 d after the causative medication was last taken[1]. Non-conventional or alternative medical therapies are being used more frequently in Western society and should be considered as a possible cause of unexplained abnormal liver function tests[2].

Estrium Whey is an alternative nutritional support therapy for women. It’s enhanced with specific nutrients including phytoestrogens, folate, antioxidants, and fiber to support healthy estrogen detoxification and hormone balance. Here, we report the first case of toxic hepatitis induced by Estrium Whey in a patient with metastatic breast cancer.

A 51-year old female with a history of metastatic breast cancer diagnosed in February 2010 came to our clinic with complaints of weakness, fatigue, jaundice and dark colored of urine beginning in the last 3 wk of estrium whey therapy which she had been taking for 3 mo as alternative treatment for her breast cancer (Table 1). She had not had contact with anyone with hepatitis. Her last chemotherapy was in July 2010, she had not used any tylenol including analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs, in the previous 6 mo, she had no history of traveling.

| Total fat | 2 g |

| Saturated fat | 0.5 g |

| Cholesterol | < 5 mg |

| Total carbohydrate | 25 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2 g |

| Sugars | 19 g |

| Protein | 15 g |

| Vitamin A (as retinyl palmitate) | 1250 IU |

| Vitamin A (as beta-carotene) | 2500 IU |

| Vitamin C (as ascorbic acid) | 60 mg |

| Vitamin D (as cholecalciferol) | 40 IU |

| Vitamin E (as d-alpha tocopheryl succinate) | 300 IU |

| Thiamin (as thiamin HCl) | 0.75 mg |

| Riboflavin | 0.85 mg |

| Niacin (as niacinamide) | 10 mg |

| Vitamin B6 (as pyridoxine HCl) | 50 mg |

| Folate (as folic acid) | 400 mcg |

| Vitamin B12 (as cyanocobalamin) | 30 mcg |

| Biotin | 150 mcg |

| Pantothenic acid (as D-calcium pantothenate) | 5 mg |

| Calcium (as calcium citrate) | 350 mg |

| Iron (as ferrous fumarate) | 9 mg |

| Phosphorus (as dipotassium phpsphate) | 260 mg |

| Iodine (as potassium iodide) | 75 mcg |

| Magnesium (as citrate) | 240 mg |

Her vital signs on admission were stable. On physical examination she was conscious and icteric, the abdomen was no tender to palpation in right upper quadrant with no palpable organomegaly. She had no stigmata of end stage liver disease. Cardiovascular and respiratory examination revealed no signs consistent with congestive heart failure or respiratory tract infection. Laboratory data at the time of admission showed: leucocytes 4300/mm3, hematocrit 37.8%, hemoglobin 13.2 g/dL, platelet 247 000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 1203 U/L (8-43), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 625 U/L (7-45), alkaline phosphatase 281 U/L (41-108), total bilirubin 5.7 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 5.4 mg/dL, albumin 3.7 g/dL (Table 1). Urinalysis revealed positive bilirubin and positive urobilinogen. Viral serologic markers were as follows: Anti hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M (IgM) negative, hepatitis B surface antigen negative, anti hepatitis B core IgM negative, anti hepatitis B surface indeterminate, anti hepatitis C virus negative, IgM and immunoglobulin G antibodies to cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and herpes simplex virus negative, metals 63 AG negative. An ultrasonography at the time of admission showed multiple hypoechoic masses in both lobes of the liver likely due to metastatic disease, two echogenic nodules in the liver which are likely hemangiomas, spleen normal size with several small hypoechoic lesions that also could be metastatic disease, intrahepatic ducts, and common ducts not dilated, gallbladder normal.

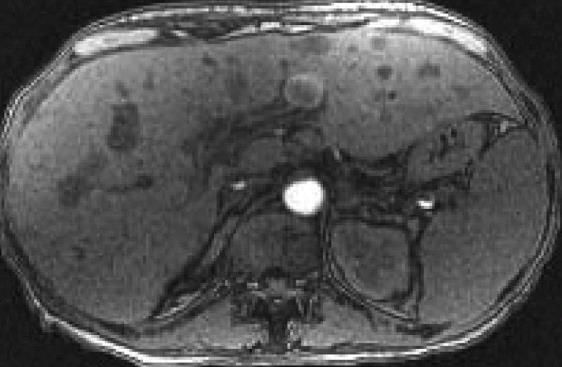

The patient was admitted to the hospital with the diagnosis of hepatitis, started on intravenous hydratation and subsequently ordered a computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, that revealed numerous masses within the liver, lesions within the spleen and prominent lymph nodes within the abdomen and pelvis consistent with metastatic disease (Figure 1), in suspicious of liver obstruction due to metastatic disease, we ordered a magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast of the abdomen that showed multiple hepatic metastases scattered throughout the left and right lobes, 4 cavernous hemangiomas in the right hepatic lobe, mild periportal edema, patent portal and hepatic veins, prominent porta hepatics lymph nodes, multiple enlarged para-aortic and aortocaval lymph nodes, diffuse gallbladder wall thickening without luminal distention or pericholecystic fluid, multiple hypointense lesions throughout the spleen due to metastatic disease (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography demonstrates no intrahepatic biliary dilatation, no common bile duct narrowing or dilatation.

Her hospital course was uneventful just for the ascending in her liver enzymes which now showed AST 2051 U/L, ALT 652 U/L, total bilirubin 10.4 mg/dL, international normalized ratio 1.1, alkaline phosphatase of 245 U/L (Table 2). The patient’s jaundice and malaise improved with supportive therapy, and she was discharged from the hospital.

| On | Days after admission | References | |||||

| admission | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | values | |

| AST | 1203 | 1600 | 1588 | 1693 | 2051 | 3050 | < 43 U/L |

| ALT | 625 | 635 | 613 | 616 | 652 | 173 | < 45 U/L |

| BILI | 5.7 | 7.5 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 14.1 | < 1 mg/dL |

| AP | 281 | 274 | 260 | 276 | 245 | 258 | 108 U/L |

Considering the clinical presentation, together with increased serum aminotransferase levels, absence of viral markers for hepatitis B, C and other hepatotropic viruses, evidence on images of no intrahepatic and extrahepatic dilatation, no enough metastatic disease to cause this rapidly progressive picture with very high AST, the final diagnosis was a toxic hepatitis induced by Estrium Whey.

Unconventional therapies have become more and more popular in Western society, and their use is not restricted to people and many of them have severe toxicities[3,4]. To define the risks of these preparations, the manufacturer should label all ingredients. Even when labeled, however, there are often significant discrepancies between the ingredients listed and the actual contents. Furthermore, these products are often adulterated with pharmaceuticals or contaminated with heavy metals[5].

The mechanism of Estrium Whey induced hepatotoxicity is not understood. The liver is the major site of metabolism of most drugs and is especially vulnerable to injury during biotransformation of these compounds. Since discontinuation of Estrium Whey was associated with resolution of symptoms and improvement of liver function abnormalities, drug induced hypersensitivity reaction seems very likely[6].

This patient was diagnosed with Estrium Whey induced toxic hepatitis. There was no history of alcohol or acetaminophen consumption, serological markers of viral hepatitis were negative and despite the liver metastasis that the patient had, the rapid increase in the liver enzymes and the histological findings were concordant with toxic hepatitis.

Peer reviewer: Ferruccio Bonino, Professor, Chief Scientific Officer, Fondazione IRCCS Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Mangiagalli e Regina Elena, Via F. Sforza 28, 20122 Milano, Italy

S- Editor Li JY L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Schiano TD. Hepatotoxicity and complementary and alternative medicines. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:453-473. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hussaini SH, Farrington EA. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury: an overview. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:673-684. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ernst E. Serious adverse effects of unconventional therapies for children and adolescents: a systematic review of recent evidence. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:72-80. [PubMed] |

| 4. | De Smet PA. Herbal remedies. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2046-2056. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ernst E. Toxic heavy metals and undeclared drugs in Asian herbal medicines. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:136-139. [PubMed] |

| 6. | But PP, Tomlinson B, Lee KL. Hepatitis related to the Chinese medicine Shou-wu-pian manufactured from Polygonum multiflorum. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1996;38:280-282. [PubMed] |