Published online Nov 27, 2012. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i11.299

Revised: October 31, 2012

Accepted: November 7, 2012

Published online: November 27, 2012

AIM: To study diagnostic laparoscopy as a tool for excluding donors on the day of surgery in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).

METHODS: This study analyzed prospectively collected data from all potential donors for LDLT. All of the donors were subjected to a three-step donor evaluation protocol at our institution. Step one consisted of a clinical and social evaluation, including a liver profile, hepatitis markers, a renal profile, a complete blood count, and an abdominal ultrasound with Doppler. Step two involved tests to exclude liver diseases and to evaluate the donor’s serological status. This step also included a radiological evaluation of the biliary anatomy and liver vascular anatomy using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and a computed tomography (CT) angiogram, respectively. A CT volumetric study was used to calculate the volume of the liver parenchyma. Step three included an ultrasound-guided liver biopsy. Between November 2002 and May 2009, sixty-nine potential living donors were assessed by open exploration prior to harvesting the planned part of the liver. Between the end of May 2009 and October 2010, 30 potential living donors were assessed laparoscopically to determine whether to proceed with the abdominal incision to harvest part of the liver for donation.

RESULTS: Ninety-nine living donor liver transplants were attempted at our center between November 2002 and October 2010. Twelve of these procedures were aborted on the day of surgery (12.1%) due to donor findings, and eighty-seven were completed (87.9%). These 87 liver transplants were divided into the following groups: Group A, which included 65 transplants that were performed between November 2002 and May 2009, and Group B, which included 22 transplants that were performed between the end of May 2009 and October 2010. The demographic data for the two groups of donors were found to match; moreover, no significant difference was observed between the two groups of donors with respect to hospital stay, narcotic and non-narcotic analgesia requirements or the incidence of complications. Regarding the recipients, our study clearly revealed that there was no significant difference in either the incidence of different complications or the incidence of retransplantation between the two groups. Day-of-surgery donor assessment for LDLT procedures at our center has passed through two eras, open and laparoscopic. In the first era, sixty-nine LDLT procedures were attempted between November 2002 and May 2009. Upon open exploration of the donors on the day of surgery, sixty-five donors were found to have livers with a grossly normal appearance. Four donors out of 69 (5.7%) were rejected on the day of surgery because their livers were grossly fatty and pale. In the laparoscopic era, thirty LDLT procedures were attempted between the end of May 2009 and October 2010. After the laparoscopic assessment on the day of surgery, twenty-two transplantation procedures were completed (73.4%), and eight were aborted (26.6%). Our data showed that the levels of steatosis in the rejected donors were in the acceptable range. Moreover, the results of the liver biopsies of rejected donors were comparable between the group A and group B donors. The laparoscopic assessment of donors presents many advantages relative to the assessment of donors through open exploration; in particular, the laparoscopic assessment causes less pain, requires a shorter hospital stay and leads to far superior cosmetic results.

CONCLUSION: The laparoscopic assessment of donors in LDLT is a safe and acceptable procedure that avoids unnecessary large abdominal incisions and increases the chance of achieving donor safety.

- Citation: Hegab B, Abdelfattah MR, Azzam A, Mohamed H, Hamoudi WA, Alkhail FA, Bahili HA, Khalaf H, Sofayan MA, Sebayel MA. Day-of-surgery rejection of donors in living donor liver transplantation. World J Hepatol 2012; 4(11): 299-304

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v4/i11/299.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v4.i11.299

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) has become an acceptable option for patients in need of liver transplantation who are not likely to receive a deceased organ in a timely fashion[1]. The accurate pretransplant evaluation of a potential live donor in LDLT is a major prerequisite for preventing postoperative liver failure and achieving donor safety. The appropriate selection of a donor for LDLT is an important aspect of achieving donor safety. In general, the utilization rate of potential donors is 28.8%[2]. The objective of this work is to present our early experience with exclusion from donation on the day of surgery in LDLT using a laparoscopic assessment technique.

Sixty-nine potential living donors were assessed for 69 recipients (58 adults and 11 children) between November 2002 and May 2009 after passing all of the phases of donor selection in our protocol. These patients were taken to the operating room for potential donation without laparoscopic assessment. Between May 2009 and October 2010, 30 potential living donors were assessed for 30 recipients (27 adults and 3 children); these patients were subjected to laparoscopic assessment of their livers prior to proceeding with the abdominal incision to harvest part of the liver for donation. In this study, we did not consider patients to be excluded if they were eliminated either in the preliminary nurse coordinator consultation or during the 3 phases of donor evaluation. The donor evaluation protocol in our center proceeded as follows: after a preliminary nurse coordinator consultation, donors with no contraindication to donation and with an ABO-compatible blood group were evaluated in three steps.

Step one of this evaluation included a clinical and social evaluation. A liver profile, hepatitis marker assessment, renal profile, complete blood count, and abdominal ultrasound with Doppler were performed in this step. Step two involved tests to exclude liver diseases and to evaluate the donor’s serological status. In addition to these examinations, step two also included an imaging evaluation of the biliary anatomy and liver vascular anatomy using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and a computed tomography (CT) angiogram, respectively. A CT volumetric study was used to calculate the volume of the liver parenchyma. We considered a graft-to-recipient body weight ratio that was equal to or greater than 0.8% to be a safe lower limit for adults, with a maximum percentage of resection in the donor liver of 60%-65%. Step three included an ultrasound-guided liver biopsy, which is a mandatory part of the evaluation; this process was performed under ultrasound guidance and consisted of three tan-core biopsies. Results of 10% or less fat infiltration were accepted if less than 50% of the donor liver was planned for resection.

Step four was first introduced during May 2009 and consisted of a laparoscopic assessment on the day of donation under general endotracheal anesthesia that occurred prior to opening the abdomen. Laparoscopic access to the abdominal cavity for the placement of a 5 mm port was attained using a Veress needle in the sub-umbilical region. A 30 degree laparoscope was used, and the liver was explored for any gross pathologies. We examined at the gross appearance, color, surface and edges of the liver.

Statistical analysis were performed with the SPSS software package for Windows (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, version 17.0, SSPS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). Relevant arithmetic means, standard deviations, numbers and percentages were measured. Categorical parameters were compared using the chi-square test, whereas numerical data were compared using the t test. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ninety-nine LDLT operations were attempted at our center between November 2002 and October 2010. Twelve of these procedures were aborted on the day of surgery (12.1%) due to donor findings, and 87 transplants were completed (87.9%).

These 87 liver transplants were divided into the following groups: Group A, which included 65 transplants that were performed between November 2002 and May 2009, and Group B, which included 22 transplants that were performed between the end of May 2009 and October 2010.

The group A donors consisted of 51 males and 14 females (78.5% and 21.5% respectively), and the group B donors consisted of 15 males and 7 females (68.2% and 31.8 respectively) with a P value of 0.49 for the gender distribution. The donors were also found to be matched between groups with respect to other demographic data, as indicated in Table 1.

| Group A donors (n = 65) | Group B donors (n = 22) | P value | |||||

| Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | ||

| Age, yr | 18-42 | 23.3 | 6.3 | 18-40 | 27.1 | 5.5 | 0.6 |

| Weight, kg | 46-86 | 64.7 | 10.1 | 51-93 | 66.8 | 11 | 0.38 |

| Height, cm | 140-190 | 166.5 | 8.4 | 152-186 | 169.3 | 10 | 0.44 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 14-28.9 | 23.5 | 3.4 | 17.4-28.4 | 23.3 | 3.4 | 0.88 |

No significant difference was observed between the donor groups regarding either hospital stay or requirements for narcotic or non-narcotic analgesia, as presented in Table 2. Similarly, as presented in Table 3, no significant difference was observed in the incidence of complications between donor groups.

| Group A donors | Group B donors | ||||||

| n = 65 | n = 22 | P value | |||||

| Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | ||

| Hospital stay, d | 4-7 | 4.9 | 1.1 | 4-6 | 4.8 | 0.6 | 0.75 |

| No. of narcotic analgesia doses per admission, doses | 3-10 | 6.3 | 2.1 | 2-8 | 5 | 1.5 | 0.42 |

| No. of non-narcotic analgesia doses per admission, doses | 10-17 | 12.9 | 1.8 | 12-16 | 13.1 | 1.2 | 0.31 |

| Group A donorsn = 65 | Group B donorsn = 22 | P value | |

| Minor biliary leak | 3 (4.6) | 1 (4.5) | 0.78 |

| Wound seroma/hematoma | 4 (6.2) | 1 (4.5) | 0.98 |

| Wound infection | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0.56 |

| Incisional hernia | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0.56 |

| Ascites | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0.56 |

In group A, the recipients were 46 males and 19 females (70.8% and 29.2% of the recipients, respectively), whereas in group B, the recipients were 15 males and 7 females (68.2% and 31.8% of the recipients, respectively), with a P value of 0.82 for the gender distribution.

The group A recipients ranged in age between 1 and 63 years, with a mean of 40.8 ± 19.4 years. The ages of the recipients in group B ranged between 1 and 68 years, with a mean of 47.6 ± 22.2 years. There was a P value of 0.3 between groups. Table 4 provides the indications for liver transplantation in each group.

| Group A recipientsn = 65 | Group B recipientsn = 22 | P value | |

| HCV cirrhosis | 29 (44.6) | 10 (45.4) | 0.95 |

| HBV cirrhosis | 11 (16.9) | 3 (13.6) | 0.98 |

| HBV and HCV cirrhosis | 1 (1.5) | 2 (9) | 0.32 |

| HCC | 14 (21.5) | 8 (36.3) | 0.27 |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 8 (12.3) | 2 (9) | 0.98 |

| Wilson’s disease | 3 (4.6) | 0 | 0.73 |

| Hyperoxaluria | 4 (6.2) | 0 | 0.55 |

| Biliary atresia | 0 | 2 (9) | 0.1 |

The recipients in group A had hospital stays ranging from 10-104 d with a mean of 30.1 ± 17 d. By contrast, the recipients in group B had hospital stays of between 12 and 98 d, with a mean of 31.2 ± 21.7 d (P = 0.75). Table 5 addresses the morbidity of both groups by reporting the incidence of different complications, including retransplantation. This table clearly indicates that there were no significant differences between the groups with respect to the incidence of different complications or retransplantation.

| Group A recipientsn = 65 | Group B recipientsn = 22 | P value | |

| Biliary complications | 20 (30.7) | 9 (40.9) | 0.50 |

| Hepatic artery thrombosis | 3 (4.6) | 1 (4.5) | 0.98 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 4 (6.2) | 1 (4.5) | 0.78 |

| Incisional hernia | 3 (4.6) | 2 (9) | 0.80 |

| Small-for-size syndrome | 3 (4.6) | 1 (4.5) | 0.98 |

| Primary non-function | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0.56 |

| Retransplantation | 7 (10.8) | 0 | 0.29 |

Within the first 2 years after liver transplant, 15 recipients died in group A compared with four deaths among group B recipients (23.1% and 18.2%, respectively, of the recipients in each group; P = 0.85).

Two of the deaths in group A were non-graft-related (one patient died from a pulmonary embolism, and the other died from massive bleeding caused by colonic angiodysplasia), whereas only one patient died due to non-graft-related causes in group B (cerebrovascular stroke). Table 6 lists the different causes of graft-related mortalities in the liver transplant recipients in both groups. This table clearly demonstrates that there were no significant differences between the groups with respect to either the total number of graft-related deaths or the individual causes of these graft-related deaths.

| Group A recipientsn = 65 | Group B recipientsn = 22 | P value | |

| Total number of graft-related deaths | 13 | 3 | 0.73 |

| Cholestatic HCV recurrence | 1 | 0 | 0.56 |

| HCC recurrence | 2 | 0 | 0.99 |

| Sepsis | 3 | 1 | 0.99 |

| Hepatic artery thrombosis | 2 | 0 | 0.99 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 3 | 2 | 0.80 |

| Small-for-size syndrome | 1 | 0 | 0.56 |

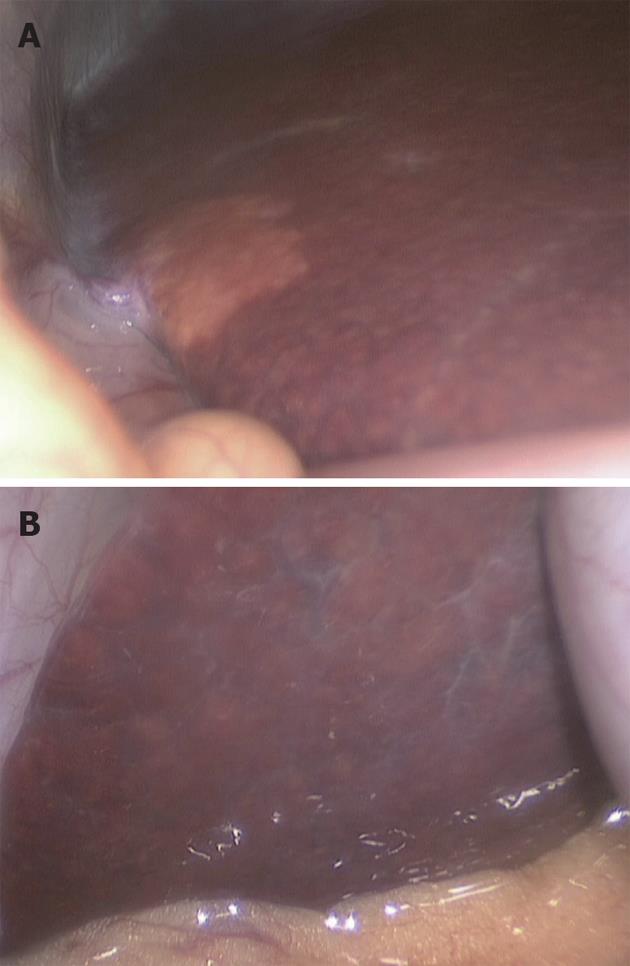

Day-of-surgery donor assessment procedures at our center have been conducted by two methods, open and laparoscopic, over two different periods of time (eras). In the first era, 69 LDLT procedures were attempted between November 2002 and May 2009. Upon the open exploration of the donors on the day of surgery, 65 donors were found to have livers with a grossly normal appearance, and 4 donors (2 males and 2 females) were found to have pale, fatty livers. One donor was found to have a pale and grossly steatotic liver, and we decided to biopsy this liver. The biopsy of this liver revealed hepatic steatosis of less than 10%, and we therefore opted to complete the procedure; unfortunately, however, the recipient of this graft developed primary non-function. In the laparoscopic era, 30 procedures were attempted between the end of May 2009 and October 2010. Twenty-two procedures were completed (73.4%), and 8 were rejected (26.6%) on the day of surgery after laparoscopic assessment. Four of the rejected donors were males, and four were females. The rejected livers were found to be pale and grossly fatty (Figure 1) with rounded borders in seven cases (87.5%) and to have a grossly fibrotic appearance in the remaining case (12.5%).

The body mass index for the rejected donors ranged from 20 kg/m2 to 28.4 kg/m2 with a mean of 23.8 ± 1.2 kg/m2. All of the rejected donors had preoperative liver biopsies, and only four of the patients demonstrated any abnormalities. Three of the rejected donors (25%) exhibited less than 5% steatosis, and one patient (8.3%) demonstrated between 5% and 10% steatosis. These data revealed that the rejected donors had steatosis in the acceptable range. Moreover, the results of the liver biopsies of rejected donors were comparable between group A and group B donors. Table 7 reports the incidence of abnormal liver biopsy findings in the donors of both groups.

| Group A donorsn = 65 | Group B donorsn = 22 | P value | |

| Steatosis < 5% | 18 (27.7) | 5 (22.7) | 0.86 |

| Steatosis 5%-10% | 4 (6.2) | 2 (9) | 0.64 |

| Steatosis 10%-15% | 6 (9.2) | 0 | 0.32 |

| Steatosis 15%-20% | 1 (3.1) | 0 | 0.56 |

| Fibrosis (stage 0-1) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0.56 |

Donor safety is the most crucial aspect of LDLT programs. The aim of donor evaluation protocols is to completely avoid donor mortality and minimize both the incidence and degree of donor morbidity. Living liver donation is associated with a small but real possibility of mortality that may approach 0.5%[3,4]. Ringe et al[5] reported 33 donor deaths and categorized them according to different degrees of certainty. Clavien et al[6] defined five grades of postoperative complications for the specific procedure of LDLT[7]. Morbidity rates vary from 8% to 35% after right-lobe liver donation[8-13] and from 9% to 40% following left or left lateral segment donation[14].

Liver biopsy is a routine step in donor evaluation in a high percentage of LDLT programs. Other methods to evaluate the fat content of the donor’s liver are less sensitive and specific than liver biopsy, and these alternatives are unable to detect any associated liver pathology. Unfortunately, liver biopsy is an invasive technique and is associated with a certain risk of complications. Recent studies have reported an incidence of major complications related to liver biopsy of 1.3%[15-17].

The risk of primary non-function after the transplantation of a steatotic graft increases in proportion with the degree of steatosis. Steatosis reduces the functional hepatic mass for both the donor and the recipient, reduces the hepatic regenerative capacity and increases the risk of injury caused by cold ischemia by altering the cell membrane fluidity or disrupting the microcirculation[18-20]. In our LDLT program, we accept up to 10% steatosis for liver grafts.

In our institution, the rate of finding a grossly fatty liver despite an acceptable liver biopsy result was approximately 5.7%. In one of the completed LDLT procedures, the liver was grossly fatty and pale; despite repeated liver biopsies that revealed an acceptable percentage of steatosis, the recipient’s post-transplantation course was complicated by primary graft non-function. This incident could indicate that relative to liver biopsy, gross liver morphology may be a more sensitive method of detecting fatty livers. Further randomized studies should be conducted to clarify this point.

According to our small series of laparoscopic donor assessments, this method proved to be both safe and useful in detecting fatty livers by gross morphology. Laparoscopic assessment provides many advantages over the assessment of donors by open exploration; in particular, it causes less pain, requires a shorter hospital stay, and achieves far superior cosmetic results.

The approximately 4- to 5-fold increase in the detection of gross liver steatosis using this method could be related to differences in samples and could indicate more sensitivity but not necessarily more specificity in detecting steatotic livers. However, this statement must be confirmed in a prospective study. Donor safety is a critical concern in LDLT, and laparoscopic donor assessment proved to be a safe and useful adjunctive measure to liver biopsy in the detection of steatotic livers. Further study is required to confirm these results.

Donor safety is considered to be the most important concern for transplant centers, health authorities and the general community. This consideration is attributed to the ethical concerns that relate to the process of donation from a perfectly healthy person who could suffer an adverse effect on his health following donation. Because the first mission of medicine is to do no harm, the issue of donor safety is extremely critical. Detailed and accurate pretransplant evaluation of a potential donor of a portion of the liver for the sake of living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is of paramount importance in ensuring donor safety and graft quality, which will translate into better outcomes for both the donor and the recipient.

Unfortunately, donor pretransplant evaluation, including liver biopsy, cannot absolutely ensure the adequacy of a potential donor, and further evaluation is needed through inspection of the liver. This inspection can only be achieved by exploration of the donor’s liver, which requires a large abdominal incision and its inherent sequelae of cosmoses, healing, analgesia requirements, hospital stay and return to work. The accomplishment of this exploration without the requirement of a large incision would represent an improvement for donors.

The introduction of laparoscopy allowed for primary abdominal exploration without the need for a large incision. This exploration enables an excellent assessment of the donor’s liver, particularly for steatosis, which can be patchy and therefore easily missed by liver biopsy.

The study results suggest that the laparoscopic assessment of donors for LDLT is a safe and acceptable procedure. The procedure avoids an unnecessarily large abdominal incision, allows for the more accurate assessment of the liver and increases the chance of achieving donor safety.

Liver transplantation refers to the replacement of a diseased liver with either an entire healthy liver or a portion of a healthy liver. Living donor liver transplant is the transplant of part of the liver from a healthy person (the donor) into the recipient. Laparoscopy is the visualization of the abdominal cavity through a very small incision using a specialized camera that transmits the images to a display system (monitor).

In this manuscript, the authors describe the utility of laparoscopic assessment of donor livers on the day of transplantation surgery. Because steatosis may be patchy and may be missed on a small core biopsy sample, the results show that the gross examination of the liver by laparoscopic assessment may result in the rejection of unacceptable donors on the day of surgery without subjecting the donors to an open procedure.

Peer reviewer: Rachel Mary Hudacko, MD, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Medical Education Building, Rm 212, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, 1 Robert Wood Johnson Place, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, United States

S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Marcos A. Right-lobe living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:S59-S63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Malagó M, Testa G, Frilling A, Nadalin S, Valentin-Gamazo C, Paul A, Lang H, Treichel U, Cicinnati V, Gerken G. Right living donor liver transplantation: an option for adult patients: single institution experience with 74 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;238:853-862; discussion 862-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Valentín-Gamazo C, Malagó M, Karliova M, Lutz JT, Frilling A, Nadalin S, Testa G, Ruehm SG, Erim Y, Paul A. Experience after the evaluation of 700 potential donors for living donor liver transplantation in a single center. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1087-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pomfret EA. Early and late complications in the right-lobe adult living donor. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S45-S49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ringe B, Strong RW. The dilemma of living liver donor death: to report or not to report? Transplantation. 2008;85:790-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518-526. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24667] [Article Influence: 1174.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ghobrial RM, Saab S, Lassman C, Lu DS, Raman S, Limanond P, Kunder G, Marks K, Amersi F, Anselmo D. Donor and recipient outcomes in right lobe adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:901-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Yong BH, Chan JK, Ng IO. Safety of donors in live donor liver transplantation using right lobe grafts. Arch Surg. 2000;135:336-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pomfret EA, Pomposelli JJ, Lewis WD, Gordon FD, Burns DL, Lally A, Raptopoulos V, Jenkins RL. Live donor adult liver transplantation using right lobe grafts: donor evaluation and surgical outcome. Arch Surg. 2001;136:425-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ito T, Kiuchi T, Egawa H, Kaihara S, Oike F, Ogura Y, Fujimoto Y, Ogawa K, Tanaka K. Surgery-related morbidity in living donors of right-lobe liver graft: lessons from the first 200 cases. Transplantation. 2003;76:158-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | De Carlis L, Giacomoni A, Sammartino C, Lauterio A, Slim AO, Forti D. Right lobe living-related liver transplant: experience at Niguarda Hospital. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1015-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shackleton CR, Vierling JM, Nissen N, Martin P, Poordad F, Tran T, Colquhoun SD. Morbidity in live liver donors: standards-based adverse event reporting further refined. Arch Surg. 2005;140:888-895; discussion 895-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yamaoka Y, Morimoto T, Inamoto T, Tanaka A, Honda K, Ikai I, Tanaka K, Ichimiya M, Ueda M, Shimahara Y. Safety of the donor in living-related liver transplantation--an analysis of 100 parental donors. Transplantation. 1995;59:224-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rinella ME, Abecassis MM. Liver biopsy in living donors. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:1123-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Brandhagen D, Fidler J, Rosen C. Evaluation of the donor liver for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S16-S28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nadalin S, Malagó M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Testa G, Baba HA, Liu C, Frühauf NR, Schaffer R, Gerken G, Frilling A. Preoperative donor liver biopsy for adult living donor liver transplantation: risks and benefits. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:980-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Selzner M, Rüdiger HA, Sindram D, Madden J, Clavien PA. Mechanisms of ischemic injury are different in the steatotic and normal rat liver. Hepatology. 2000;32:1280-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fukumori T, Ohkohchi N, Tsukamoto S, Satomi S. The mechanism of injury in a steatotic liver graft during cold preservation. Transplantation. 1999;67:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seifalian AM, Chidambaram V, Rolles K, Davidson BR. In vivo demonstration of impaired microcirculation in steatotic human liver grafts. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |