Published online Oct 27, 2012. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i10.288

Revised: October 15, 2012

Accepted: October 22, 2012

Published online: October 27, 2012

A 77-year-old man underwent percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) for acute cholecystitis as a preoperative procedure; however, he suddenly suffered cardiopulmonary arrest 4 h after the PTGBD and died. There were three centesis scars for the PTGBD, and only one pathway from the most dorsal centesis scar reached the gallbladder. Microscopically, the PTGBD pathway crossed and injured the intrahepatic arterial wall, and hepatic parenchymal bleeding extended along the PTGBD pathway to the inferior surface of the liver. Blood flowed to the peritoneal cavity through a small gap between the liver and gallbladder. Consequently, the PTGBD caused lethal bleeding. When the percutaneous transhepatic cholangio drainage/PTGBD pathway runs close to vessels near the liver surface, it might be necessary to deal with the possibility of rapid and lethal peritoneal bleeding.

- Citation: Ihama Y, Fukazawa M, Ninomiya K, Nagai T, Fuke C, Miyazaki T. Peritoneal bleeding due to percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage: An autopsy report. World J Hepatol 2012; 4(10): 288-290

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v4/i10/288.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v4.i10.288

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangio drainage (PTCD) and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) are effective procedures that promptly release congestive bile from the body. The safety and reliability of PTCD/PTGBD have been greatly increased by the use of ultrasonic guidance for centesis[1]. Recently, there have been very few reports of deaths directly resulting from PTCD/PTGBD in patients without severe preexisting disease[2]. Here we report a patient who died from bleeding shock resulting from PTGBD, and we discuss the causes of the lethal bleeding based on autopsy findings.

A man in his early seventies was admitted to the emergency department of a hospital with the chief complaint of abdominal pain that had been increasing for the past several days. Ultrasonography (US) showed a swelling gallbladder filled with debris and stones. Abdominal CT indicated an invagination of the stones into the neck of the gallbladder. The results of blood chemical tests administered at admission were as follows: white blood cell: 10 000 /L, hemoglobin: 14.5 g/dL, platelet (Plt): 17.6 × 104/L, total-bilirubin: 0.6 mg/mL, aspartate aminotransferase: 17 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase: 8 IU/L, lactate Dehydrogenase: 176 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase: 246 IU/L, Amylase: 129 IU/L, C-reactive protein: 7.04 mg/dL. The patient was diagnosed with acute cholecystitis due to bile stones. His general condition was stable. He had no bleeding disorder or coagulation abnormality, and he was not taking anticoagulant agents, such as warfarin or aspirin. Two years earlier, however, he was diagnosed with aortic dissection and from then on had been managed conservatively with antihypertensive agents. In the meantime, ultrasound-guided percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration or PTGBD was selected as a preoperative procedure. He had been complaining of severe abdominal pain despite the intravenous administration of pentazosine, an analgesic. Thus he could neither remain still on his back nor hold his breath. With the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, the third centesis finally reached the gallbladder, after two failures of centesis. Because the thick bile or debris in the gallbladder could not be adequately aspirated through a puncture needle, the operators changed their strategy and placed a catheter in the patient for PTGBD. The drainage catheter egested a thick bile, and no dye leakage or hemorrhage was revealed by post-PTGBD radiographic examination. Four hours after PTGBD, the patient suffered a sudden cardiopulmonary arrest in bed. At 14 h after PTGBD, he died despite undergoing intensive care.

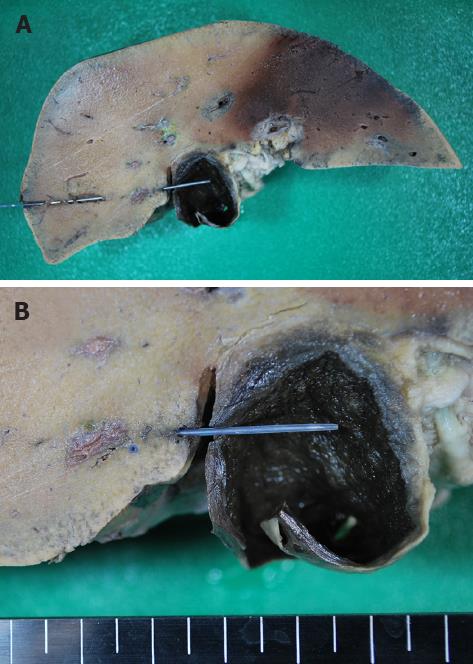

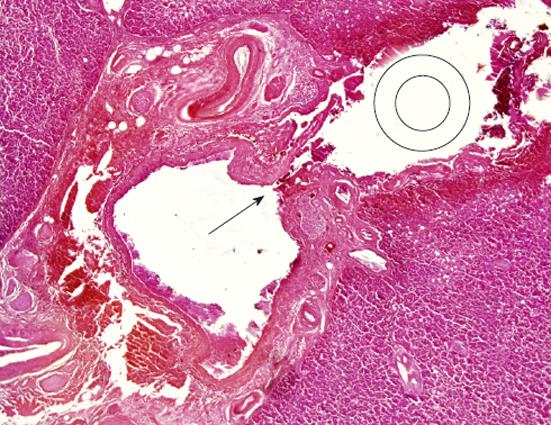

The body was 165 cm in length and weighed 90 kg. The abdomen was tense with distension, and there were three puncture scars on the right side (Figure 1). The PTGBD drainage catheter had been removed in the hospital. As shown in Figure 1, the three puncture scars were labeled (A), (B) and (C). Volumes of blood with clots of 1050 mL and 1500 mL were present in the right thoracic and peritoneal cavities, respectively, and large numbers of clots were found around the gallbladder and inferior surface of the liver. The gallbladder wall was thick due to inflammation, and there were approximately 100 black stones in the gallbladder. Among the three pathways of centesis, only pathway (C) reached the gallbladder, transversely through the right hepatic lobe (Figure 2A). Macroscopically, pathway (C) crossed interlobular tissue near the liver surface and was exposed to the peritoneal cavity between the liver and gallbladder before entering the gallbladder (Figure 2B). Histological serial cross-sections of pathway (C) revealed that the pathway gradually came close to interlobular vessels and injured an intrahepatic artery (Figure 3). The bleeding from that artery extended along pathway (C) into the peritoneal cavity. The main organs were anemic, and there were no injuries to the other vessels and organs. The endothelial surface of the aorta showed severe atherosclerosis but no dissection.

We attributed the patient’s death to abdominal and thoracic bleeding resulting from injury of the intrahepatic artery caused by PTGBD.

Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis issued in Japan in 2005 and based on scientific evidence, recommend emergency cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis[3]. However, PTCD/PTGBD is an effective procedure for decompressing an obstructed biliary system. Thus preoperative PTCD/PTGBD for acute cholecystitis remains a frequent first- choice therapy[2]. According to a study published in 2008, the rates of the technical success of and clinical response to this treatment were 100% and 90%, respectively[2]. Potential complications of PTCD/PTGBD can occur because of its invasiveness; the most serious complications are sepsis and bleeding[4]. The incidence of hemorrhage related with PTCD/PTGBD has been reported to be 2.5%; however, Burke et al[4] estimate that the actual incidence is twice as high as the recorded number. In recent randomized studies by Ito et al[2], the mortality rate after PTCD/PTGBD was found to be 2.2%, and all deaths were caused by preexisting disease, not by PTCD/PTGBD directly. Hemorrhage is not a rare complication of PTCD/PTGBD, but it is not likely to be fatal without there being a preexisting disease. We believe that the present case was an extremely rare and unfortunate accident.

In this case, the death was caused directly by bleeding due to PTGBD. We believe that this death was attributable to two factors: (1) an intrahepatic artery was injured near the surface of the liver; (2) a drainage pathway was partially opened into the peritoneal cavity between the liver and gallbladder. In the liver, many hepatic arteries, central veins and portal veins are entwined as in the mesh of a net; hence, there is always a risk of hemorrhage when performing the PTCD/PTGBD procedure. In this patient, no anatomical aberrations of the hepatic vessels were detected by US or in the autopsy examination. Generally, a PTGBD catheter is inserted into the gallbladder through the gallbladder bed under US[3]. Hence, the catheter never enters the peritoneal cavity. However, when the gallbladder is filled with congestive bile and stones, it is difficult to determine by US whether the pathway runs through the gallbladder bed or not. In this case, the increased tension and swelling of the gallbladder caused us to misread the ultrasound which seemed to show the catheter pathway running through the gallbladder bed. However, the bile drainage shrank the gallbladder, thereby creating a space between the gallbladder and liver. Textbooks recommend that PTGBD be performed from the patient’s anterior direction, because following a longitudinal pathway against the gallbladder can reduce the risk that the drainage catheter will protrude from the liver. However, if the patient cannot remain still on his or her back because of the pain, the operator may need to puncture the patient’s right side away from the recommended point.

It is not clear when the hepatic artery was ruptured. The ultrasound-guided PTGBD had been performed without vessel injury, and the post-PTGBD examination detected no bleeding in the liver or around the gallbladder. Therefore, we consider that the arterial injury occurred after the drainage catheter was placed. The PTGBD catheter running near the artery damaged the wall of the artery gradually by rubbing against it with slight movements. Since no vessel injury was detected during or soon after the PTCD/PTGBD, it is possible that the drainage catheter damaged the vessel wall after the procedure. In particular, when the PTCD/PTGBD pathway runs in close proximity to vessels near the liver surface, it might be necessary to deal with the possibility of rapid and lethal peritoneal bleeding, not only during but also after the procedure.

Peer reviewers: Wahid Wassef, MD, MPH, FACG, UMass Memorial Health Care, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, 55 Lake Avenue North, University Campus, Room S6-727, Worcester, MA 01655, United States; Pierce Kah-Hoe Chow, Professor, Department of General Surgery, Singapore General Hospital, Outram Raod, Singapore 169608, Singapore

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Yan JL

| 1. | Makuuchi M, Yamazaki S, Hasegawa H, Bandai Y, Ito T, Watanabe G. Ultrasonically guided cholangiography and bile drainage. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1984;10:617-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O. The usefulness of percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis. JJBA. 2008;22:632-637. |

| 3. | Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Sekimoto M, Miura F, Wada K, Hirota M, Yamashita Y. Background: Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Burke DR, Lewis CA, Cardella JF, Citron SJ, Drooz AT, Haskal ZJ, Husted JW, McCowan TC, Van Moore A, Oglevie SB. Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and biliary drainage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:S243-S246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |