Published online Dec 27, 2011. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v3.i12.292

Revised: September 26, 2011

Accepted: October 3, 2011

Published online: December 27, 2011

Hepatitis B is one of the leading causes of chronic hepatitis in developing countries, with 5% to 15% of the population carrying virus. The high prevalence is due to failure to adopt appropriate measure to confine the spread of infection. Most hepatitis B patients present with advanced diseases. Although perinatal transmission is believed to be an important mode, most infections in the developing world occur in childhood and early adulthood. Factors in developing countries associated with the progression of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) include co-infections with human immunodeficiency virus, delta hepatitis virus, hepatitis C virus, alcohol intake and aflatoxin. Treatment protocols extrapolated from developed countries may need modifications according to the resources available. There is some controversy as to when to start treatment, with what medication and for how long? There is now enough evidence to support that hepatitis B patients should be considered for treatment if they show persistently elevated abnormal aminotransferase levels in the last 6 mo, checked on at least three separate occasions, and a serum hepatitis B virus DNA level of > 2000 IU/mL. Therapeutic agents that were approved by Pure Food and Drug Administration are now available in many developing countries. These include standard interferon (INF)-α, pegylated INF-α, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir and telbivudine. Drug resistance has emerged as a major challenge in the management of patients with CHB. The role of the universal vaccination program for effective control of hepatitis B cannot be emphasized enough.

- Citation: Abbas Z, Siddiqui AR. Management of hepatitis B in developing countries. World J Hepatol 2011; 3(12): 292-299

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v3/i12/292.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v3.i12.292

Hepatitis B is the leading cause of chronic viral hepatitis across the world. More than two billion people worldwide show serological evidence of exposure to this virus, comprising about one third of the global population and approximately 350-400 million carry the chronic infection[1,2]. Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection leads to cirrhosis and is still a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma in many parts of the developing world[3,4]. For children under 1 year, the risk of chronic infection is 90%[5]. About 25% of adults who become chronically infected during childhood die prematurely from liver cancer or cirrhosis, caused by its chronic infection[2]. But if adults are infected by hepatitis B virus (HBV) after childhood, 90% will eventually fully recover. Hepatitis B causes an estimated one million deaths per year worldwide[6].

It is estimated that 5 % to 15% of the population are chronic carriers of hepatitis B in developing countries, whereas in North America and Western Europe only 1% of the population is chronically infected. Chronic HBV infection is highly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean region, the Amazon basin and the Caribbean[7-9]. Hepatocellular carcinoma seems to be more common in Africa and Asia than in other parts of the world due to Hepatitis B infection.

Many developing countries often face significant health and hygiene challenges that predispose to the transmission of hepatitis viruses. Most hepatitis B patients present with advanced disease. Contributing factors leading to late presentation include ignorance, poverty, lack of easy accessibility to healthcare centers, lack of trained personnel and diagnostic facilities, un-affordability of expensive drugs and consultations from quacks and traditional healers that misguide patients.

Perinatal transmission is believed to be the most important mode in regions of developing world with high and intermediate HBV prevalence rates[10]. Transmission occurs from mother to child or from child to child, mainly through cuts, bites, scrapes and scratches. Although most infections in the developing world occur in childhood and early adulthood, a significant proportion of non-immune adults remain at risk to healthcare-acquired infections. HBV remains a major nosocomial pathogen in many hospitals[11]. Transmission may occur due to unsafe injections, blood transfusions and lack of awareness of infection control[12,13]. Healthcare providers may be unaware of the natural history of hepatic cellular cancer (HCC) and the need for continuous lifetime monitoring of HBV infection status[4]. Sexual contact also accounts for some HBV transmission.

The natural history of CHB has been defined into different phases: the immune tolerant phase, the immune reactive phase and the inactive carrier phase and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) negative disease[14-17]. In the immune tolerant phase, HBeAg is positive, HBV DNA is elevated, abnormal aminotransferase (ALT) is usually normal and liver inflammation is absent or minimal. The immune reactive phase is characterized by ALT elevation, HBV DNA levels > 2000 IU/mL and active liver inflammation and fibrosis of various degrees. A more vigorous cytotoxic T-cell response may occur eventually, resulting in seroconversion from HBeAg to anti-HBe during this phase. After seroconversion, most patients go into the inactive hepatitis B carrier phase characterized by normal ALT levels, low levels of HBV DNA (< 2000 IU copies/mL) and improvement of liver inflammation and fibrosis over time, provided they remain in the inactive hepatitis B phase. These patients may move from the inactive hepatitis phase back to the immune reactive phase, either by experiencing a reversion from anti-HBe to HBeAg or having HBeAg negative CHB with elevated HBV DNA levels > 2000 IU/mL and elevated ALT[18,19]. A small fraction of patients lose surface antigen over years with the disease becoming inactive. Occult infection is associated with negative hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), undetectable HBV DNA in serum which is detectable on liver biopsy as persistent of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) within the nucleus of infected cells[20]. Hepatitis B can reactivate when patient is immunosupressed in such a state[21,22].

There may be some factors operating more in developing countries associated with the progression of CHB, like co-infections with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), delta hepatitis virus (HDV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol intake and aflatoxin. Individuals with chronic HBV infection need lifelong monitoring for the development of active chronic hepatitis and HCC.

Newly diagnosed CHB individuals should be evaluated by relevant history, identifying risk factors and appropriate physical examination[23]. Laboratory tests should include complete blood counts, liver panel, α fetoprotein, HBeAg, anti-HBe antibody status and HBV DNA levels. Every patient should have an ultrasound examination of liver. Other tests that are still not included in the guidelines are quantification of HBsAg and HBV genotype. It is possible to quantify the HBsAg level, which would help improve management and monitoring of hepatitis patients. This test is now becoming available in developing countries and is not very expensive. It reflects transcriptionally active cccDNA while HBV DNA levels reflect active viral replication[24,25]. HBV genotype influences the outcome of the disease as well as outcome of therapy with interferon (INF)[26]. However, in countries like Pakistan where a single genotype predominates, it would be unnecessary to check genotype in every case[27].

Co-infections with other infections should be ruled out by checking HIV, HDV and HCV antibodies. To stage the chronic active disease, liver biopsy is considered to be the gold standard. However, help may also be taken from Fibroscan and non invasive tests. Chen et al[28] reported a model to predict compensated cirrhosis due to HBV infection using the findings of ultrasound examination of liver and blood tests.

Screening and vaccination for hepatitis A may not be necessary in areas with high childhood exposure. Screening and vaccination of household/sexual contacts for HBV is recommended.

Evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of CHB have been developed by three of the world’s major liver societies, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[29], the European Association for the Study of the Liver[30] and the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver[31]. These guidelines are reviewed and updated every 2-3 years. National guidelines of local societies from developing countries are also available[32]. Evidence-based guidelines require sufficient evidence to support any recommendations that are made and thus may not cover all situations which a clinician caring for hepatitis B in developing countries may encounter. Treatment can cost thousands of dollars per year and is not available to the majority of patients in these countries.

Labeling of HBV infected patients as “inactive carriers” based on ALT alone may be misleading. A fair proportion of patients with CHB and persistently normal ALT have HBV DNA ≥ 5-log copies/mL and significant histological fibrosis[33]. There have been suggestions for lowering the upper cut off of normal range for ALT to 19 IU/mL for women and 30 IU/mL for men, as higher levels have been shown to be associated with significant liver disease[34,35]. These cut off levels differentiate the really “inactive carriers” from those with active disease with histological damage, who need to be treated. Studies have shown that mildly elevated ALT less than two time upper limit of normal (< 2 ULN) may also be associated with significant underlying liver disease and does not predict a lower risk of long-term complications[36].

HBV DNA detection and quantification form an integral part of disease assessment, disease activity and response to therapy. HBV DNA viremia levels correlate positively with the inflammatory grade and fibrosis stage[37]. Cut off value of HBV DNA of 20 000 IU/mL for the initiation of treatment has been challenged. The R.E.V.E.A.L study showed that the value of > 104 copies (2000 IU/mL) might be associated with a higher risk for development of cirrhosis and is independent of HBeAg status and serum ALT levels[38]. Three other studies have also suggested that CHB may occur at lower levels of HBV DNA between 104 copies/mL and 105 copies/mL[39-41]. Moreover, with the single point assessment of HBV DNA level, the accurate differentiation of CHB e-antigen negative infection from inactive carriers is difficult because of wide and frequent HBV-DNA fluctuations. It has been suggested that single-point combined HBsAg and HBV-DNA quantification (HBsAg < 1000 IU/mol and HBV DNA ≤ 2000 IU/mL) provides the more accurate identification of inactive carriers[42].

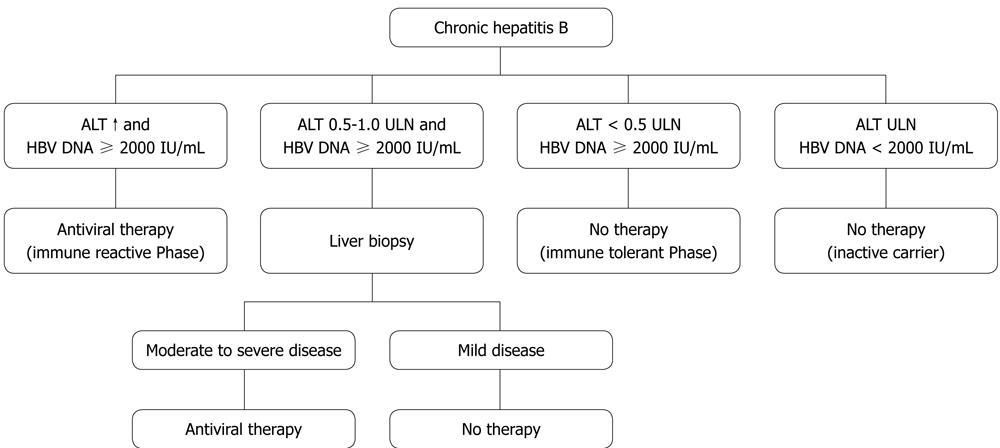

Hepatitis B patients should be considered for treatment if they show persistently elevated ALT levels in the last 6 mo, checked on at least three separate occasions, and a serum HBV DNA level of > 2000 IU/mL[30,32]. If ALT fluctuates near the upper limit of normal or remains > 0.5 times ULN all the time with elevated HBV DNA > 2000 IU/mL, liver biopsy is advocated (Figure 1). Patients with HBV DNA positive < 2000 IL/mL and normal ALT levels should be monitored every 3 mo for the first year then every 6 mo thereafter to assess development of active disease. Cirrhotic patients with detectable HBV DNA should be treated irrespective ALT level. Ultrasound examination of liver should be repeated every 6-12 mo.

Two types of agents used for treatment are INF (standard and PEG) and oral nucleosides/nucleotides analogues (NUCs). The former has advantages of having a finite treatment period, no resistance and durable HBeAg seroconversion. While treating with INF, patients infected with genotype A do better than genotype D in Caucasians and genotype B better than genotype C in Asians[26]. INFs cannot be prescribed in cirrhotic patients with decompensated disease. On the other hand, NUCs are easy to administer and monitor, have fewer side effects and can be given in cirrhotics. Therapeutic agents that were approved by Pure Food and Drug Administration include standard INF-α, pegylated INF-α, lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir and telbivudine[16].

Lamivudine is a cheap option in developing countries but is easily susceptible to resistance[43]. The documented figures for lamivudine resistance mutation rises up to 23 %-65% after 1-5 years of treatment[44]. Adefovir dipivoxil is a less effective agent compared to other agents and offers a high chance of resistance, as is telbivudine although it is a more potent drug[45,46]. Entecavir and tenofovir are effective options bearing the least chance of developing resistance with a high potency against the HBV and can be opted as first line option straight away[47]. Tenofovir is a potent inhibitor of HBV viral suppression[48,49]. Emtricitabine (cytosine analog), which is a co inhibitor for both HIV and HBV, is structurally similar to lamivudine with the same resistant mutations and the results are comparable[50].

Thymosin α has been used in Asian countries as an immunomodulatory agent. It has a delayed virological response which is seen after the completion of a year of treatment[51]. Various combination therapies using both INF and NUCs are also used for an additive synergistic effect and greater suppression of virus along with reducing the risks of emergence of resistance[52]. For example, INF and lamivudine when used in combination in wild type virus is more potent than monotherapy with lower rates of resistance to lamivudine[53,54].

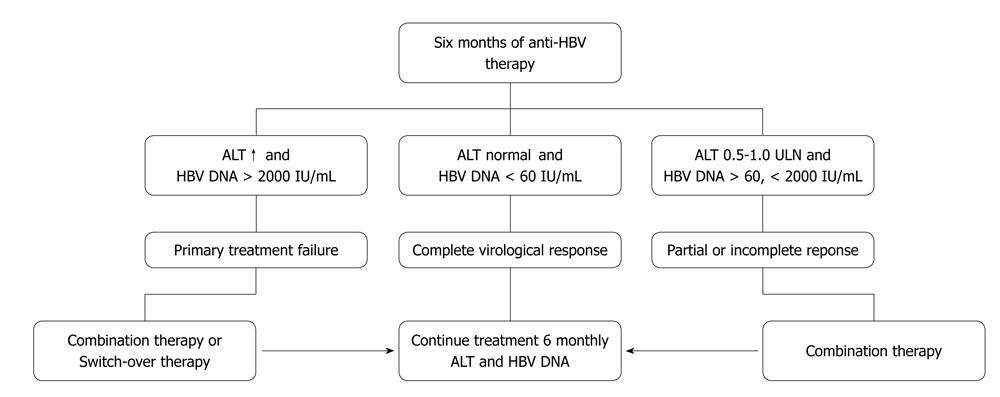

Assessment of treatment efficacy can be made by monitoring the parameters during the initial phase, maintenance phase and after completion of treatment. A later sustained response can be established at 6 mo and 1 year after the end of treatment. Figure 2 summarizes the possible scenarios after 6 mo of therapy with NUCs.

In clinical practice, serum HBV DNA and ALT monitoring is the most practical method to detect response and virological breakthrough. It is the key to prevent possible hepatic flares and decompensation[55]. It should be done at 3 mo, 6 m into treatment and thereafter every 6 mo. Serum HBeAg should be checked every 6 mo in patients who are initially HBeAg positive in order to determine the time of e-antigen sero-conversion. Anti-HBe antibody should be checked after HBeAg becomes negative. The quantitative PCR is an expensive test and may not be affordable for many patients from developing countries. In such cases testing at month three may be omitted. In less ideal situations when the test is not available, monitoring with ALT alone every 3 mo would suffice. In patients with virological breakthrough, necessary modifications should be instituted and medication compliance reinforced. Resistance testing (genotyping) should be carried out, where available, in cases of viral breakthrough or suboptimal viral suppression.

There is also a potential role for on-treatment monitoring of serum HBsAg titres to predict virological response during both INF therapy and oral nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy[24]. Good immune control results in dramatic reduction of HBsAg levels. Monitoring HBsAg levels may help to identify patients who would respond to finite therapy and achieve sustained immune control in case of pegylated INF and clear HBsAg in long term treatment with nucleoside analogs[56]. Treatment with pegylated INF may be stopped early in patients who fail to show significant decline in HBsAg levels at week 12 or 24[57].

Drug resistance, as mentioned above, has emerged as a major challenge in the management of patients with CHB. Emergence of resistant HBV strains leads to virological and biochemical breakthrough, and can further result in histological deterioration during treatment, hepatic decompensation and death. Several factors predispose to development of resistance, including high viral load, resistant variants, slow response, prior therapy with a nucleoside analogue leading to cross resistance, high body mass index, along with patient immune status and compliance, all play a role in the development of resistance to anti viral therapy[58-61].

Entecavir was found to be safe and effective for the treatment of Japanese adults with lamivudine-refractory CHB[62]. In vitro studies however, demonstrate that entecavir is less effective against lamivudine-resistant HBV strains in comparison to wild-type; 20-30-fold higher concentrations are required for polymerase inhibition. This is because lamivudine resistance already preselects two of the three mutations required for entecavir resistance. Virological breakthrough to entecavir requires at least three substitutions. Accumulating evidence from these settings suggests that entecavir switch is not an optimal treatment for patients with lamivudine resistance[63]. Tenofovir may be of value in such cases of baseline lamivudine or adefovir resistance[64]. While dealing with resistance, sequential monotherapy and use of agents with similar cross resistance profiles should be avoided. An add-on approach is preferred. A combination of tenofovir with emtricitabine in one tablet has been licensed for the treatment of HIV infection. This combination, not freely available in developing countries, may be of value in dealing resistant cases of hepatitis B as well.

The end points of therapy should be normalization of ALT, seroconversion of HBsAg and HBeAg, suppression of HBV DNA and improvement of histological features on liver biopsy to achieve sustained suppression of viral replication and remission of disease[65]. HBsAg seroconversion is difficult to achieve with the current therapy and HBV DNA supression (< 2000 IU/mL) is the primary desirable objective to prevent the progression of active disease[66,67]. Duration of treatment varies from 1 year to 3-5 years or may be for life in some cases. INF-based regimens have a short term period, usually 1 year compared to NUCs.

In patients with HBeAg positive disease, CHB treatment may be stopped after confirmation of undetectable HBV DNA, HBeAg loss and formation of anti-HBe antibodies on two separate occasions 3 mo apart after the consolidation therapy of at least 6 mo[68]. In patients with HBeAg negative disease, the end point of therapy remains undefined. Ideally therapy should be continued until the patient has achieved HBsAg seroconversion, a task difficult to achieve. Treatment discontinuation can be considered if undetectable HBV-DNA has been documented on three separate occasions 6 mo apart[31,32]. However, a risk of relapse remains on stopping treatment.

There is a risk of up to 50% that individuals with chronic HBV infection will develop an exacerbation of hepatitis during chemotherapy treatment for malignancies. Prophylactic nucleoside analogs are indicated and should be continued for at least 4 mo after completing chemotherapy[68]. Similar risk has been shown in persons treated with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors for rheumatic disorders or inflammatory bowel disease, and these individuals should also be given lamivudine prophylaxis[69,70]. Decision about starting treatment during pregnancy must weigh pros and cons to both mother and baby. Tenofovir, telbivudine and lamivudine appear to be safe in pregnancy. Treatment of immune reactive mothers may be started during pregnancy[71,72].

The role of the universal vaccination program in effective control of hepatitis B cannot be emphasized enough. The best example is of Taiwan where HBsAg seroprevalence amongst children 1-15 years decreased from 9.8% in 1984 to 0.7%[73]. The vaccine prevents HBV infection in 90%-100% of people who produce sufficient antibody responses[74]. All highly endemic countries included hepatitis B vaccination in their national childhood immunization. All children and adolescents younger than 18 years old and not previously vaccinated should receive the vaccine. World Health Organization recommends that routine infant vaccination against HBV forms part of all national immunization schedules. In countries with high mother-to-child transmission rates, the first dose of HBV vaccine is ideally given within 24 h of birth. A combination of vaccine plus hepatitis B immunoglobulin is superior in decreasing risk of transmission of hepatitis B from a HBsAg positive mother to infant[75]. The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization is supporting hepatitis B vaccination programs in developing countries[76].

Two possible dosing schedules are considered appropriate to prevent mother-to-child HBV infections[77]. Three dose schedule: first dose given at birth, second and third doses given concurrently with the first and third doses of DTP vaccine. Four-dose schedule: first dose given at birth, three doses given concurrently with other Expanded Program on Immunization vaccines. Catch-up campaign strategies may be considered for countries where adult risk factors are associated with acute HBV infection. Targeting adolescents and high-risk adults, such as prisoners or health care workers, can supplement routine infant vaccination[78]. In regions, where there is a high rate of infection, catch-up vaccination is not recommended, as most adults will have already been exposed to the virus. Initial vaccination confers protection against HBV infection even after anti-HBs antibody declines below detectable levels[75]. However, the recommendation of a booster dose after 10-15 years of initial HBV vaccination, although controversial, seems prudent[79,80].

There is a high prevalence of hepatitis B in many developing countries due to the failure to adopt appropriate measures to confine the spread of infection. There is a need to define the minimal requirements for delivery of optimal care to hepatitis B patients, establish research institutions and collaborate with international organizations to describe the natural history and response to treatment in the underdeveloped world. Treatment protocols extrapolated from developed countries may need modifications according to the resources available. With recent advances in hepatitis B virology and natural history of the disease, many recommendations are now becoming unresolved issues.

Peer reviewer: Can-Hua Huang, PhD, Oncoproteomics group, The State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, Sichuan University, No. 1 Keyuan Rd 4, Gaopeng ST, High Tech Zone, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China

S- Editor Zhang SJ L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733-1745. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kane M. Global programme for control of hepatitis B infection. Vaccine. 1995;13 Suppl 1:S47-S49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bosch FX, Ribes J, Díaz M, Cléries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S5-S16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1799] [Cited by in RCA: 1816] [Article Influence: 86.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24 Suppl 1:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hyams KC. Risks of chronicity following acute hepatitis B virus infection: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:992-1000. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gish RG, Gadano AC. Chronic hepatitis B: current epidemiology in the Americas and implications for management. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:787-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mahoney FJ. Update on diagnosis, management, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:351-366. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kane A, Lloyd J, Zaffran M, Simonsen L, Kane M. Transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses through unsafe injections in the developing world: model-based regional estimates. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:801-807. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Custer B, Sullivan SD, Hazlet TK, Iloeje U, Veenstra DL, Kowdley KV. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S158-S168. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Francis DP, Favero MS, Maynard JE. Transmission of hepatitis B virus. Semin Liver Dis. 1981;1:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lynch P, Pittet D, Borg MA, Mehtar S. Infection control in countries with limited resources. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65 Suppl 2:148-150. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hauri AM, Armstrong GL, Hutin YJ. The global burden of disease attributable to contaminated injections given in health care settings. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:7-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Abbas Z, Jafri W, Shah SH, Khokhar N, Zuberi SJ. PGS consensus statement on management of hepatitis B virus infection--2003. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:150-158. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lok AS, Hussain M, Cursano C, Margotti M, Gramenzi A, Grazi GL, Jovine E, Benardi M, Andreone P. Evolution of hepatitis B virus polymerase gene mutations in hepatitis B e antigen-negative patients receiving lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 2000;32:1145-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, Fleischer R, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2007;45:1056-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1794] [Cited by in RCA: 1778] [Article Influence: 98.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Martinot-Peignoux M, Boyer N, Colombat M, Akremi R, Pham BN, Ollivier S, Castelnau C, Valla D, Degott C, Marcellin P. Serum hepatitis B virus DNA levels and liver histology in inactive HBsAg carriers. J Hepatol. 2002;36:543-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lok AS, Lai CL. Acute exacerbations in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Incidence, predisposing factors and etiology. J Hepatol. 1990;10:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hadziyannis SJ, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;34:617-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR, Buendia MA, Chen DS, Colombo M, Craxì A, Donato F, Ferrari C, Gaeta GB. Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2008;49:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Knöll A, Pietrzyk M, Loss M, Goetz WA, Jilg W. Solid-organ transplantation in HBsAg-negative patients with antibodies to HBV core antigen: low risk of HBV reactivation. Transplantation. 2005;79:1631-1633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Marcellin P, Giostra E, Martinot-Peignoux M, Loriot MA, Jaegle ML, Wolf P, Degott C, Degos F, Benhamou JP. Redevelopment of hepatitis B surface antigen after renal transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1432-1434. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lok AS, Heathcote EJ, Hoofnagle JH. Management of hepatitis B: 2000--summary of a workshop. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1828-1853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 540] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nguyen T, Thompson AJ, Bowden S, Croagh C, Bell S, Desmond PV, Levy M, Locarnini SA. Hepatitis B surface antigen levels during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B: a perspective on Asia. J Hepatol. 2010;52:508-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Brunetto MR. A new role for an old marker, HBsAg. J Hepatol. 2010;52:475-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cooksley WG. Do we need to determine viral genotype in treating chronic hepatitis B? J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:601-610. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Abbas Z, Muzaffar R, Siddiqui A, Naqvi SA, Rizvi SA. Genetic variability in the precore and core promoter regions of hepatitis B virus strains in Karachi. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen YP, Dai L, Wang JL, Zhu YF, Feng XR, Hou JL. Model consisting of ultrasonographic and simple blood indexes accurately identify compensated hepatitis B cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1228-1234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2169] [Article Influence: 135.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in RCA: 1154] [Article Influence: 72.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liaw YF, Suh DJ, Omata M. 2008 APASL guidelines for HBV management. Available from: http://www.apasl.info/guidelinesHBV.html. |

| 32. | Abbas Z, Jafri W, Hamid S. Management of hepatitis B: Pakistan Society for the Study of Liver Diseases (PSSLD) practice guidelines. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20:198-201. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Kumar M, Sarin SK, Hissar S, Pande C, Sakhuja P, Sharma BC, Chauhan R, Bose S. Virologic and histologic features of chronic hepatitis B virus-infected asymptomatic patients with persistently normal ALT. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1376-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, Tobias H. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: 2008 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1315-1341; quiz 1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kariv R, Leshno M, Beth-Or A, Strul H, Blendis L, Kokia E, Noff D, Zelber-Sagie S, Sheinberg B, Oren R. Re-evaluation of serum alanine aminotransferase upper normal limit and its modulating factors in a large-scale population study. Liver Int. 2006;26:445-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kim HC, Nam CM, Jee SH, Han KH, Oh DK, Suh I. Normal serum aminotransferase concentration and risk of mortality from liver diseases: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328:983. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Madan K, Batra Y, Jha JK, Kumar S, Kalra N, Paul SB, Singh R, Duttagupta S, Panda SK, Acharya SK. Clinical relevance of HBV DNA load in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Trop Gastroenterol. 2008;29:84-90. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1164] [Cited by in RCA: 1174] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Manesis EK, Papatheodoridis GV, Sevastianos V, Cholongitas E, Papaioannou C, Hadziyannis SJ. Significance of hepatitis B viremia levels determined by a quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2261-2267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chu CJ, Hussain M, Lok AS. Quantitative serum HBV DNA levels during different stages of chronic hepatitis B infection. Hepatology. 2002;36:1408-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yuen MF, Ng IO, Fan ST, Yuan HJ, Wong DK, Yuen JC, Sum SS, Chan AO, Lai CL. Significance of HBV DNA levels in liver histology of HBeAg and Anti-HBe positive patients with chronic hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2032-2037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Brunetto MR, Oliveri F, Colombatto P, Moriconi F, Ciccorossi P, Coco B, Romagnoli V, Cherubini B, Moscato G, Maina AM. Hepatitis B surface antigen serum levels help to distinguish active from inactive hepatitis B virus genotype D carriers. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Hadziyannis SJ, Papatheodoridis GV, Dimou E, Laras A, Papaioannou C. Efficacy of long-term lamivudine monotherapy in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2000;32:847-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, Yao GB, Cui ZY, Schiff ER, Dienstag JL, Heathcote EJ, Little NR, Griffiths DA. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1714-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 584] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Heathcote EJ, Rasenack J, Bzowej N. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576-2588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 601] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Ma J. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1743-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, Lok AS, Han KH, Goodman Z, Zhu J. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1107] [Cited by in RCA: 1088] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kuo A, Dienstag JL, Chung RT. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:266-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | van Bömmel F, Wünsche T, Mauss S, Reinke P, Bergk A, Schürmann D, Wiedenmann B, Berg T. Comparison of adefovir and tenofovir in the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2004;40:1421-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Lim SG, Ng TM, Kung N, Krastev Z, Volfova M, Husa P, Lee SS, Chan S, Shiffman ML, Washington MK. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of emtricitabine in chronic hepatitis B. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:49-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Chan HL, Tang JL, Tam W, Sung JJ. The efficacy of thymosin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1899-1905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Locarnini S, Hatzakis A, Heathcote J, Keeffe EB, Liang TJ, Mutimer D, Pawlotsky JM, Zoulim F. Management of antiviral resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:679-693. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Chan HL, Leung NW, Hui AY, Wong VW, Liew CT, Chim AM, Chan FK, Hung LC, Lee YT, Tam JS. A randomized, controlled trial of combination therapy for chronic hepatitis B: comparing pegylated interferon-alpha2b and lamivudine with lamivudine alone. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:240-250. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, Farci P, Hadziyannis S, Jin R, Lu ZM, Piratvisuth T, Germanidis G, Yurdaydin C. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1206-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 874] [Cited by in RCA: 856] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Fung J, Lai CL, Yuen MF. Hepatitis B virus DNA and hepatitis B surface antigen levels in chronic hepatitis B. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:717-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Cai W, Xie Q, An B, Wang H, Zhou X, Zhao G, Guo Q, Gu R, Bao S. On-treatment serum HBsAg level is predictive of sustained off-treatment virologic response to telbivudine in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:22-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Rijckborst V, Hansen BE, Cakaloglu Y, Ferenci P, Tabak F, Akdogan M, Simon K, Akarca US, Flisiak R, Verhey E, Van Vuuren AJ, Boucher CA, ter Borg MJ, Janssen HL. Early on-treatment prediction of response to peginterferon alfa-2a for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B using HBsAg and HBV DNA levels. Hepatology. 2010;52:454-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Zoulim F. Mechanism of viral persistence and resistance to nucleoside and nucleotide analogs in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2004;64:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Thibault V, Di Martino V, Caumes E, Bricaire F, Opolon P, Katlama C, Poynard T. Long-term incidence of hepatitis B virus resistance to lamivudine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Hepatology. 1999;30:1302-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Fung SK, Chae HB, Fontana RJ, Conjeevaram H, Marrero J, Oberhelman K, Hussain M, Lok AS. Virologic response and resistance to adefovir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2006;44:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, Hunt C, Brown N, Woessner M, Boehme R, Condreay L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Suzuki F, Toyoda J, Katano Y, Sata M, Moriyama M, Imazeki F, Kage M, Seriu T, Omata M, Kumada H. Efficacy and safety of entecavir in lamivudine-refractory patients with chronic hepatitis B: randomized controlled trial in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1320-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Wichroski MJ, Xu D, Yang J, Wilber RB. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Berg T, Marcellin P, Zoulim F, Moller B, Trinh H, Chan S, Suarez E, Lavocat F, Snow-Lampart A, Frederick D. Tenofovir is effective alone or with emtricitabine in adefovir-treated patients with chronic-hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1207-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Sorrell MF, Belongia EA, Costa J, Gareen IF, Grem JL, Inadomi JM, Kern ER, McHugh JA, Petersen GM, Rein MF. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:104-110. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update of recommendations. Hepatology. 2004;39:857-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | EASL Jury. EASL International Consensus Conference on Hepatitis B. 13-14 September, 2002: Geneva, Switzerland. Consensus statement (short version). J Hepatol. 2003;38:533-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Liang R, Lau GK, Kwong YL. Chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation for cancer patients who are also chronic hepatitis B carriers: a review of the problem. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:394-398. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Xunrong L, Yan AW, Liang R, Lau GK. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation after cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy--pathogenesis and management. Rev Med Virol. 2001;11:287-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Esteve M, Saro C, González-Huix F, Suarez F, Forné M, Viver JM. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut. 2004;53:1363-1365. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Available from: http://www.apregistry.com/forms/exec-summary.pdf. |

| 73. | Ni YH, Chang MH, Huang LM, Chen HL, Hsu HY, Chiu TY, Tsai KS, Chen DS. Hepatitis B virus infection in children and adolescents in a hyperendemic area: 15 years after mass hepatitis B vaccination. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:796-800. [PubMed] |

| 74. | André FE. Overview of a 5-year clinical experience with a yeast-derived hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccine. 1990;8 Suppl:S74-S78; discussion S79-S80. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Zuckerman JN. Review: hepatitis B immune globulin for prevention of hepatitis B infection. J Med Virol. 2007;79:919-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Martin JF, Marshall J. New tendencies and strategies in international immunisation: GAVI and The Vaccine Fund. Vaccine. 2003;21:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Sheffield JS, Hickman A, Tang J, Moss K, Kourosh A, Crawford NM, Wendel GD Jr. Efficacy of an accelerated hepatitis B vaccination program during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1130-1135. |

| 78. | Sukriti NT, Sethi A, Agrawal K, Agrawal K, Kumar GT, Kumar M, Kaanan AT, Sarin SK. Low levels of awareness, vaccine coverage, and the need for boosters among health care workers in tertiary care hospitals in India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1710-1715. [PubMed] |

| 79. | Hepatitis B vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004;79:255-263. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Lu JJ, Cheng CC, Chou SM, Hor CB, Yang YC, Wang HL. Hepatitis B immunity in adolescents and necessity for boost vaccination: 23 years after nationwide hepatitis B virus vaccination program in Taiwan. Vaccine. 2009;27:6613-6618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |