Published online Jun 27, 2010. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i6.226

Revised: March 10, 2010

Accepted: March 17, 2010

Published online: June 27, 2010

AIM: To investigate the possibility of shortening the duration of peginterferon (Peg-IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV) combination therapy by incorporating interferon-β (IFN-β) induction therapy.

METHODS: A one treatment arm, cohort prospective study was conducted on seventy one patients. The patients were Japanese adults with genotype 1b chronic hepatitis C, HCV-RNA levels of ≥ 5.0 Log IU/mL or 100 KIU/mL, and platelet counts of ≥ 90 000/μL. The treatment regimen consisted of a 2 wk course of twice-daily administration of IFN-β followed by 24 wk Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy. We prolonged the duration of the Peg-IFN plus RBV therapy to 48 wk if the patient requested it.

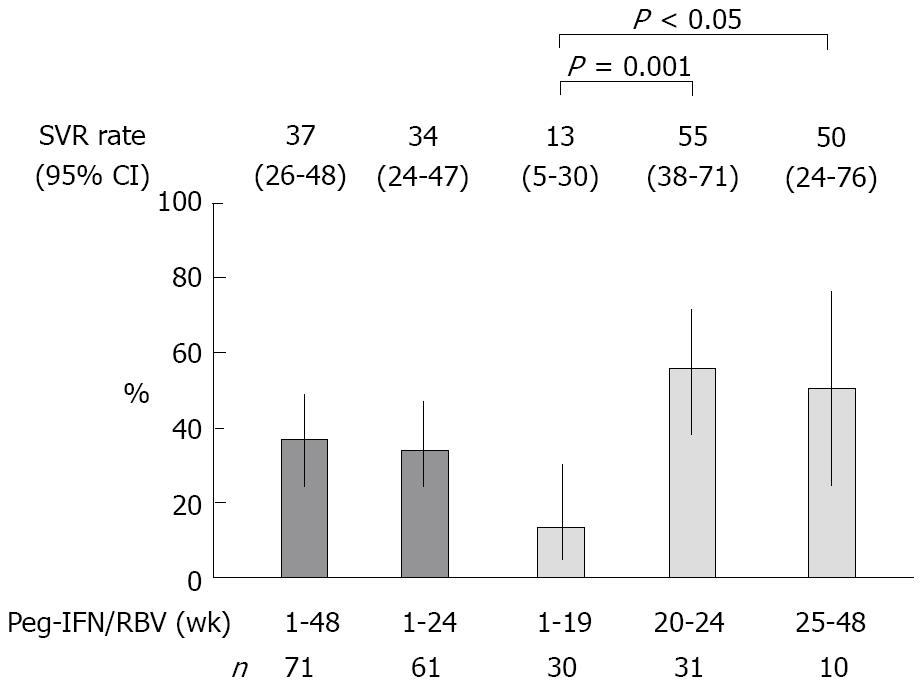

RESULTS: The patients, including 44% males, were characterized by an median age of 63 years (range: 32-78 years), an median platelet count of 13.9 (range: 9.1-30.6) × 104/μL, 62% IFN-naïve, and median HCV-RNA of 6.1 (range: 5.1-7.2) Log IU/mL. The sustained virologic response (SVR) rates were 34% (Peg-IFN: 1-24 wk, n = 61, 95% confidence interval (CI): 24%-47%) and 55% (Peg-IFN: 20-24 wk, n = 31, 95% CI: 38%-71%, P < 0.001; vs Peg-IFN: 1-19 wk). The SVR rate when the administration was discontinued early was 13% (Peg-IFN: 1-19 wk, n = 30, 95% CI: 5%-30%), and that when the administration was prolonged was 50% (Peg-IFN: 25-48 wk, n = 10, 95% CI: 24%-76%, P < 0.05; vs Peg-IFN: 1-19 wk). In the patients who received 20-24 wk of Peg-IFN plus RBV, only the higher platelet count (≥ 130 000/μL) was significantly correlated with the SVR (odds ratio: 11.680, 95% CI: 2.3064-79.474, P = 0.0024). In 45% (14/31) of the patients with a higher platelet count (≥ 130 000/μL) before therapy, the HCV-RNA level decreased to below 3.3 Log IU/mL at the completion of IFN-β, and their SVR rate was 93% (13/14) after 20-24 wk administration of Peg-IFN plus RBV.

CONCLUSION: These results suggest the possibilities of shortening the duration of Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy by actively reducing HCV-RNA levels using the IFN-β induction regimen.

- Citation: Okushin H, Morii K, Uesaka K, Yuasa S. Twenty four-week peginterferon plus ribavirin after interferon-β induction for genotype 1b chronic hepatitis C. World J Hepatol 2010; 2(6): 226-232

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v2/i6/226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v2.i6.226

The administration of peginterferon (Peg-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) for 48 wk is currently the standard treatment for genotype 1b chronic hepatitis C. Interferon (IFN) plus RBV combination therapy is more effective than IFN monotherapy[1,2], and, unlike conventional IFN, Peg-IFN needs to be administered only once a week. However, in some cases, subjective side effects such as general fatigue, rashes, stomatitis, anorexia, taste abnormalities, and anemic symptoms develop, which, along with laboratory abnormalities such as decreased hemoglobin levels and reduced neutrophil and platelet counts, necessitates the reduction of RBV or discontinuation of RBV and/or IFN. When the total dose of IFN or RBV is insufficient, the efficacy of therapy is also unsatisfactory[3,4].

Recent studies have reported that only when HCV-RNA has become negative after 4 wk of treatment (rapid virologic response: RVR) in patients with a low viral level, high sustained virologic response (SVR) rate can be expected even if the duration of administration is shortened to 24 wk[5-9]. Although, in general, RVR rate is only 15%-20% in genotype 1b chronic hepatitis C patients[10], it is important to conduct studies on the possibility of reducing the duration of the patient’s physical pain by avoiding excessive administration.

In Japan, interferon-β (IFN-β) can is approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. A characteristic of IFN-β is that dividing its administration between equal morning and evening doses increases the HCV-RNA reduction rate[11-15]. Studies have reported that the administration of 3 million units each of IFN-β in the morning and evening for 2 wk reduces HCV-RNA levels by 3 Log IU/mL in many cases, whereas the co-administration of Peg-IFN and RBV decreases them by 1-2 Log IU/mL[16,17], clearly indicating that the former regimen results in a higher rate of HCV-RNA decrease in the early phase of treatment.

We speculated that an enforced reduction in HCV-RNA levels would shorten the duration of treatment in more patients, including those with a high viral load. In this study, chronic hepatitis C patients with a high viral load of genotype-1b hepatitis C virus were administered IFN-β for 2 wk as induction therapy, followed by 24 wk Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy, and its therapeutic effect was evaluated.

We studied Japanese adult chronic hepatitis C patients who had visited our hospital between October 2006 and January 2009, and received IFN-β followed by Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy. They had HCV genotype 1b, with an HCV-RNA level of ≥ 100 KIU/mL or ≥ 5.0 Log IU/mL. Those with any of the following were excluded: other concomitant viral hepatitis, autoimmune liver disease, drug-induced liver injury, cirrhosis, renal failure, hypersensitivity to IFN or RBV, concomitant HCC, a PLT count of < 90 000/μL, or a serum albumin level of < 3.5 g/dL. The study was conducted in accordance with the institutional ethical procedures and the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment in this study. Seventy-one patients enrolled in this study.

A one arm, cohort prospective study was conducted, in a pilot fashion. Patients were initially administered IFN-β for 2 wk, followed by Peg-IFN-α2a or Peg-IFN-α2b for 24 wk, which was extended to 48 wk if the patient wished at the completion of Peg-IFN. During administration of Peg-IFN, RBV was concomitantly used.

Three million IU of IFN-β (FERON®, TORAY Industries, Inc.) was dissolved in 100 mL of physiological saline or 5% glucose for injection , and the solution was administered twice daily by intravenous drip infusion over 30 min in the morning (9:00-10:00) and evening (19:00-20:00). To prevent IFN-β-induced fever, 60 mg of loxoprofen sodium was administered 30 min before the start of the drip infusion. Subsequent to IFN-β, 180 µg of Peg-IFN-α2a (Pegasys®, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co.) or 1.5 μg/kg of Peg-IFN-α2b (Pegintron®, Schering-Plough Co.) was administered once weekly. RBV (Copegus®,

Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., when Pegasys® was used, or REBETOL®, Schering-Plough Co., when Pegintron® was used) was administered at a dose of 600 mg/d (200 mg after breakfast and 400 mg after dinner) to patients weighing < 60 kg, 800 mg/d (400 mg after breakfast and 400 mg after dinner) to those weighing 60-80 kg, and 1 000 mg/d (400 mg after breakfast and 600 mg after dinner) to those weighing > 80 kg. The daily dose of RBV was reduced by 200 mg when the hemoglobin level decreased to < 10 g/dL, and RBV was discontinued when the hemoglobin level fell to < 8.5 g/dL. When side effects made the continued administration difficult, or when HCV-RNA levels did not decrease, IFN was discontinued at the discretion of the physician.

Patients were screened for the study by HCV-RNA quantification, HCV genotyping using RT-PCR, and biochemical and hematological tests. During and after IFN administration, patients were followed-up by employing biochemical and hematological tests, HCV-RNA quantification, quantitative and qualitative HCV-RNA assays, and urinalysis. Serum HCV-RNA was measured using the Cobas Amplicor HCV Monitor Test version 2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, detection range: 5-5 000 KIU/mL), Cobas Amplicor HCV Monitor Test version 1.0 (Roche Diagnostics, detection range: 0.5-500 KIU/mL), and Cobas Taqman HCV Test (Roche Diagnostics, detection range: 1.2-7.8 Log IU/mL). Qualitative serum HCV-RNA determination was performed using the Amplicor assay (Roche Diagnostics, detection sensitivity: 50 IU/mL). Urinary protein was measured by the pyrogallol red method.

An SVR was defined as the persistent absence of detectable HCV-RNA (by the Amplicor or Taqman HCV Test) for 6 mo after the cessation of treatment. In this study, a rapid virologic response (RVR) was defined as a serum HCV-RNA level of < 50 copies/mL (qualitatively HCV-RNA-negative or < 1.7 Log IU/mL by the Taqman HCV Test) at 4 wk after the start of IFN (2 wk after the start of Peg-IFN). A complete early virologic response was defined as the absence of HCV-RNA (by the Amplicor or Taqman HCV Test) at 12 wk after the start of IFN (10 wk after the start of Peg-IFN). The end of the treatment response was defined as the absence of HCV-RNA (by the Amplicor or Taqman HCV Test) at the cessation of Peg-IFN.

The significance of differences was evaluated by the χ2 test, paired t-test, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t-test, or analysis of variance. Nominal logistic regression analysis was used for the analysis of SVR-related variables. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP® software version 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc.).

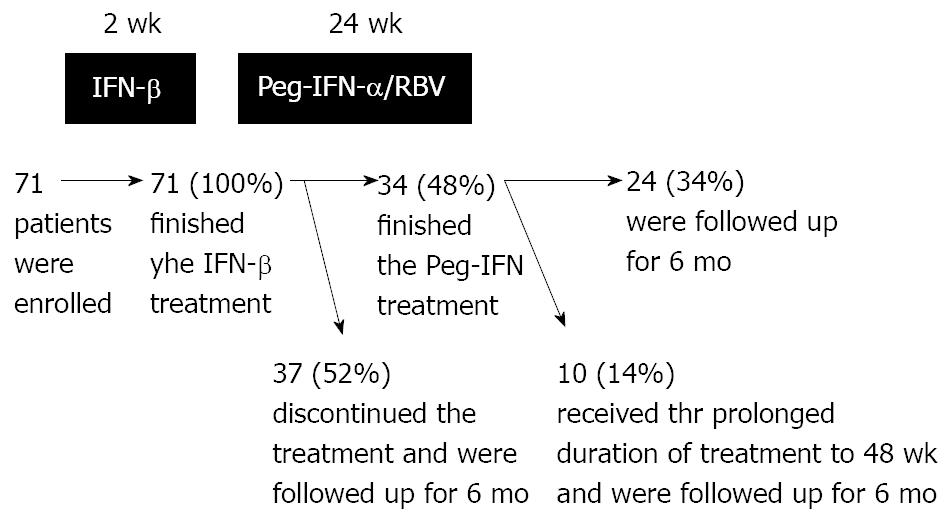

The durations of IFN treatment and the numbers of patients are shown in Figure 1. During administration of Peg-IFN, 37 (52%) patients discontinued the treatment: one patient due to work commitments, 11 (15%) patients whose HCV-RNA levels did not decrease, and 25 (35%) patients due to side effects.

The patients’ backgrounds are shown in Table 1. When HCV-RNA levels were determined using the Amplicor HCV monitor, the results (in KIU/mL) were converted to Log IU/mL.

| Background | |

| n of patients | 71 |

| Male [n (%)] | 31 (44) |

| Age (yr) | 63 (32-78) |

| Body weight > 60 kg [n (%)] | 33 (46) |

| HCV-RNA (Log IU/mL) | 6.1 (5.1-7.2) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 97 (27-513) |

| Platelet count [× 104/μL] | 13.9 (9.1-30.6) |

| 9.0 to 13.0 [n (% )] | 28 (39) |

| ≥ 13.0 [n (% )] | 43 (61) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (3.5-4.5) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.6 (10.5-16.9) |

| Interferon-naïve [n (%)] | 44 (62) |

| Peginterferon-α2a/-α2b (n) | 34/37 |

| Initial dose of ribavirin | 38/30/3 |

| 600/800/1 000 (mg/d) (n) |

Figure 2 shows the SVR rate and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Next, the patient background variables by virologic response were analyzed univariately (Table 2). When HCV-RNA levels were determined using the Amplicor HCV monitor, the results (in KIU/mL) were converted to Log IU/mL. Since the age, body weight, platelet count, hemoglobin level, and dosing duration were SVR-related variables in the patients who received Peg-IFN for 1-24 wk, and the age and platelet count were SVR-related variables in the patients who received that for 20-24 wk, nominal logistic regression analysis was performed regarding these variables (Table 3).

| Dosing duration of peginterferon plus ribavirin | ||||

| 1-24 wk | 20-24 wk | |||

| SVR non-SVR | P value | SVR non-SVR | P value | |

| n of patients | 21 | 17 | ||

| 40 | 14 | |||

| Male [n (%)] | 12 (57) | 0.0636b | 10 (59) | 0.1493c |

| 13 (33) | 4 (29) | |||

| Age (yr) | 58 (35-74) | 0.0030a | 58 (35-74) | 0.0134a |

| 65 (37-78) | 63 (58-71) | |||

| Body weight > 60 kg [n (%)] | 13 (62) | 0.0441b | 10 (59) | 0.0669c |

| 14 (35) | 3 (21) | |||

| HCV-RNA (Log IU/mL) | 5.8 (5.1-6.9) | 0.1685a | 6.0 (5.2-6.9) | 0.9967a |

| 6.1 (5.1-7.2) | 6.1 (5.2-6.6) | |||

| Alanine amino-transferase (U/L) | 97 (52-269) | 0.7699a | 86 (57-138) | 0.6410a |

| 93 (27-513) | 80 (28-260) | |||

| Platelet count (× 104/μL) | 16.8 (10.9-30.6) | 0.0020a | 17.0 (10.9-30.6) | 0.0007a |

| 13.3 (9.1-24.0) | 11.4 (9.1-15.4) | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (3.5-4.4) | 0.7410a | 3.9 (3.5-4.2) | 0.9211a |

| 3.9 (3.5-4.5) | 3.9 (3.5-4.5) | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.4 (11.4-15.4) | 0.0126a | 14.5 (11.4-15.4) | 0.1379a |

| 13.1 (10.5-15.4) | 13.5 (10.7-15.4) | |||

| Interferon-naïve [n (%)] | 12 (57) | 0.6847b | 9 (53) | 0.8150b |

| 25 (63) | 8 (57) | |||

| Peginterferon-α2a/-α2b (n) | 12/9 | 0.2016b | 9/8 | 0.4607c |

| 16/24 | 10/4 | |||

| Dosing duration of peginterferon (wk) | 24 (4-24) | 0.0009a | 24 (21-24) | 0.5082a |

| 15 (2-24) | 24 (21-24) | |||

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value1 |

| Dosing duration of peginterferon: 1-24 wk (n = 61) | ||

| Age < 65 yr | 1.3210 (0.2140-8.1481) | 0.7586 |

| Body weight > 60 kg | 3.7283 (0.6986-25.865) | 0.1257 |

| Platelet count ≥ 130 000/μL | 15.301 (2.5378-155.22) | 0.0018 |

| Hemoglobin ≥ 14.0 g/dL | 4.7957 (0.9337-30.599) | 0.0606 |

| Dosing duration of Peg-IFN 20-24 wk (vs 1-19 wk) | 33.551 (5.5858-352.77) | < 0.0001 |

| Dosing duration of peginterferon: 20-24 wk (n = 31) | ||

| Age < 65 yr | 1.1028 (0.1670-6.6558) | 0.9149 |

| Platelet count ≥ 130 000/μL | 11.680 (2.3064-79.474) | 0.0024 |

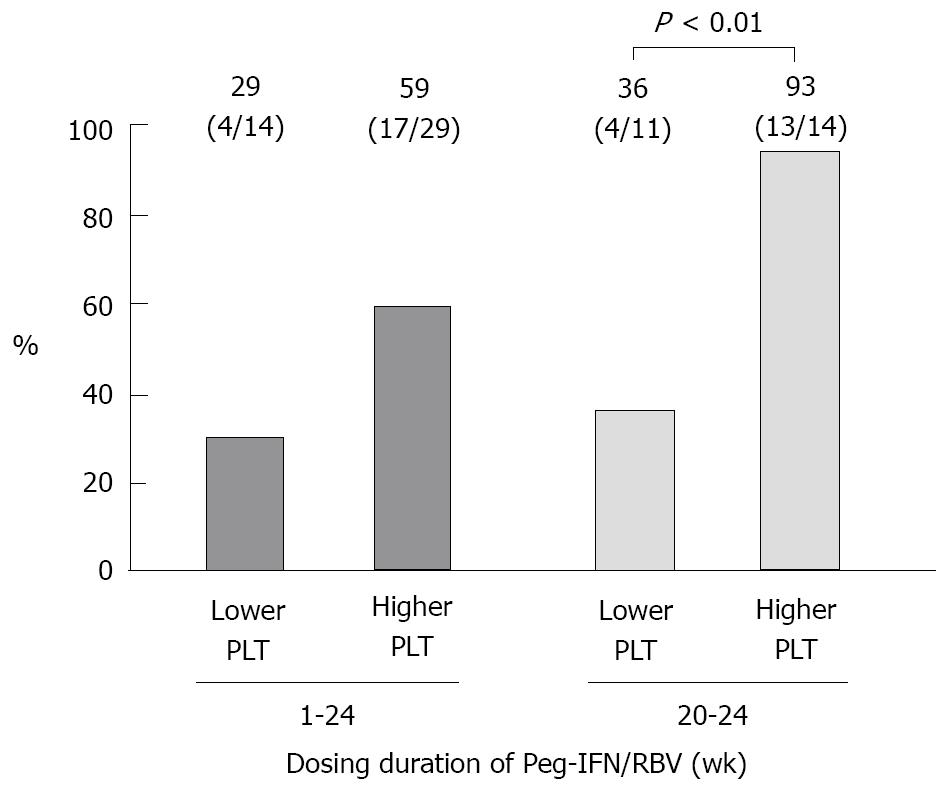

The HCV-RNA reduction and SVR rate were evaluated (Table 4). The relapse rate was 46% (18/39) and 29% (7/24) in the patients who received Peg-IFN for 1-24 wk and those for 20-24 wk, respectively. In Table 4, when HCV-RNA levels were determined using the Amplicor HCV monitor, the results (in KIU/mL) were converted to Log IU/mL. The SVR rates associated with the platelet count (identified as an independent factor by multivariate analysis) in patients whose HCV-RNA levels decreased at the end of IFN-β treatment are shown in Figure 3.

| Response outcome | IFN-β1n (%)1 | HCV-RNA1 | RVR n (%) | cEVR n (%) | ETR n (%) |

| Dosing duration of peginterferon: 1-24 wk (n = 61) | |||||

| Yes | 43 (70) | 6.0 (5.1-7.1)b | 15 (25) | 36 (59) | 39 (64) |

| SVR | 21 (49)a | 5.8 (5.1-6.9) | 7 (47) | 20 (56)c | 21 (54)d |

| Non-SVR | 22 (51)a | 6.0 (5.1-7.1) | 8 (53) | 16 (44)c | 18 (46)d |

| No | 18 (30) | 6.2 (5.5-7.2)b | 46 (75) | 25 (41) | 22 (36) |

| SVR | 0 (0)a | - | 14 (30) | 1 (4)c | 0 (0)d |

| Non-SVR | 18 (100)a | 6.2 (5.5-7.2) | 32 (70) | 24 (96)c | 22 (100)d |

| Dosing duration of peginterferon: 20-24 wk (n = 31) | |||||

| Yes | 25 (81) | 6.0 (5.2-6.9) | 11 (35) | 24 (77) | 24 (77) |

| SVR | 17 (68)e | 6.0 (5.2-6.9) | 7 (64) | 17 (71)f | 17 (71)g |

| Non-SVR | 8 (32)e | 5.7 (5.2-6.6) | 4 (36) | 7 (29)f | 7 (29)g |

| No | 6 (19) | 6.4 (5.5-6.6) | 20 (65) | 7 (23) | 7 (23) |

| SVR | 0 (0)e | - | 10 (50) | 0 (0)f | 0 (0)g |

| Non-SVR | 6 (100)e | 6.4 (5.5-6.6) | 10 (50) | 7 (100)f | 7 (100)g |

In the patients who received Peg-IFN for 25-48 wk, the SVR rate of patients whose HCV-RNA levels were lower than 3.3 Log IU/mL at the end of IFN-β treatment was 5/7. Among these patients, the SVR rate of those whose preoperative platelet counts were higher than 130 000 was 3/4, and that of those with lower platelet counts was 2/3. The three other patients whose HCV-RNA levels were not decreased at the end of IFN-β treatment were non-SVR.

No patients discontinued IFN-β treatment because of side effects. The highest body temperature after administration of IFN-β was lower than 37.0°C (98.6°F) in 85% (60/71) of patients. Of 11 patients who had a fever above 37.0°C (98.6°F), 4 (6%) developed a fever above 38°C (100.4°F), which was resolved within two days. Twenty percent (14/71) of patients developed proteinuria during IFN-β treatment, and showed a urinary protein level of ≥ 300 g/mL at the end of IFN-β treatment (at 2 wk). Subsequently, urinary protein became negative by 2 wk after Peg-IFN treatment. The mean platelet count before IFN-β treatment was 14.7 ± 4.1(× 104/μL), it decreased to 7.3 ± 3.2(× 104/μL) (P < 0.0001) at the end of IFN-β treatment (2 wk), and returned toward the pretreatment level (10.5 ± 4.8 × 104/μL, P < 0.0001) at 4 wk (at 2 wk of Peg-IFN treatment), although it remained lower than the pretreatment level (paired t-test).

Peg-IFN side effects leading to treatment discontinuation were nephrotoxicity, decreased hemoglobin, and physical symptoms (fatigue, anorexia, and anemia) in 1 (1%), 3 (4%), and 21 (30%) patients, respectively. In 30 (42%) of the 71 patients, the RBV dose was reduced because the hemoglobin level fell below 10 g/dL during Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy. The hemoglobin level before IFN-β treatment was 13.6 ± 1.3 g/dL, which rose to 14.1 ± 1.4 g/dL at the end of IFN-β (2 wk) (P < 0.0001, paired t-test). The hemoglobin level at the end (or discontinuation) of Peg-IFN treatment was 11.0 ± 1.5 g/dL, which was lower than that at the end of IFN-β treatment (P < 0.0001, paired t-test). The lowest hemoglobin level during Peg-IFN treatment was 10.5 ± 1.5 g/dL.

The aim of this study was to investigate the possibility of shortening the duration of Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C with a high viral load of genotype 1b by previously administering a 2 wk course of a twice-daily IFN-β regimen, which has been reported to be highly effective in reducing HCV-RNA, as described below.

A clinical trial of 48 wk Peg-IFN-α2a plus RBV combination therapy in 199 chronic hepatitis C Japanese patients, with a mean age of 52.0 years and a platelet count of more than 90 000/μL, including genotype 1b (92.0%), high viral load (44.2%, > 850 KIU/mL), women (31.7%) and IFN-naïve patients (49.7%), reported an SVR rate of 56.3% (103/183, genotype 1b)[18]. The EVR rate of IFN-naïve patients in genotype 1b was 75% (73/97) and 77% (56/73) of them achieved an SVR. Treatment was discontinued in 16.6% (33/199), being due to side effects in 13.6% (27/199). In another open study of 48-wk Peg-IFN-α2b plus RBV combination therapy in 586 genotype 1b chronic hepatitis C Japanese patients, with a mean age of 57.8 ± 10.3 years and a mean platelet count of (161 ± 52) × 103/μL, including women (45.2%), and 48.9% IFN-naïve patients, Furusyo et al[19] noted that they achieved an overall SVR rate of 42.4% (249/586), with those treated for less than 24, 24-47, and 48 wk achieving SVR rates of 4.7 (5/105), 36.4 (12/33), and 51.8% (232/448), respectively. Treatment was discontinued in 23.5% (138/586), being due to side effects in 14.1% (83/586) and failure of the HCV-RNA level to decrease in 3.8% (22/586).

In the present study, although the duration of treatment was shortened by one half, the SVR rate in the patients who received Peg-IFN treatment for 20-24 wk was 55%, and was comparatively higher than those studies cited above. However, presumably due to the high treatment discontinuation rates (52 vs 16.6 and 23.5%, respectively; 35 vs 13.6 and 14.1%, respectively, due to side effects) the SVR rate in the patients who received Peg-IFN treatment for 1-24 wk was low (34 vs 56.3 and 42.4%, respectively). We speculate that the treatment discontinuation rates were high because, in the present study: (1) the patients were less tolerant of side effects such as general fatigue, because their age was high, at 63 (median, range: 32-78) vs 52.0 (median) and 57.8 ± 10.3 (mean, standard deviation) years in other studies, or the percentage of women was high, at 56 vs 31.7 and 45.2%, respectively; and (2) treatment was discontinued early in more patients (15% vs none or 3.8%, respectively) because HCV-RNA did not decrease during the administration of IFN-β or Peg-IFN plus RBV.

Next, we performed subgroup analysis to sample a group of patients showing a high SVR rate. Since other studies have reported the importance of the RVR as an indicator for shortened treatment duration[5-9], we also evaluated it in the present study. Although, generally, the RVR rate of patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C is only 15%-20%[10], a meta-analysis of studies on the shortening of the treatment duration reported that among patients who achieved RVR, 84%-96% and 83%-100% of patients with an baseline HCV-RNA level of < 400 000 IU/mL achieved an SVR by 24 and 48 wk of treatment, respectively, showing no significant difference in the SVR rate between these two groups of patients[9]. Although only patients with a high viral load were included in the present study, good RVR rates of 25 and 35% were achieved in the patients who received Peg-IFN treatment for 1-24 wk and those for 20-24 wk, respectively, by actively reducing HCV-RNA levels through the use of IFN-β induction therapy (Table 4). However, the SVR rate among the patients who achieved an RVR in the present study was only 47% to 64%, and was clearly lower compared with the above-cited reports. These results suggest that an RVR is not necessarily an appropriate predictor of an SVR when administering IFN-β induction therapy.

When the platelet count (closely correlated with an SVR), among the patient background variables, was combined with the HCV-RNA level at the end of IFN-β treatment, we were able to predict a higher SVR rate. That is, as shown in Figure 3, 45% (14/31) of the patients who received Peg-IFN treatment for 20-24 wk, with a pretreatment platelet count of ≥ 130 000/µL and a HCV-RNA level of < 3.3 Log IU/mL at the end of IFN-β treatment, achieved an SVR rate of 93% (13/14). Thus, we were able to identify an important indicator for determining the duration of treatment when administering Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy after the IFN-β induction regimen.

In Japan, the use of IFN-β aiming to enhance viral clearance in the early phase of treatment when administering induction therapy has been reported[20-23]. A characteristic of IFN-β is that the administration in equally divided doses in the morning and evening increases the HCV-RNA reduction rate[11-15], as we first reported (in Japanese) in 1995[24]. In a subsequent study, 18 (13 genotype 1b, 4 genotype 2a, and 1 genotype 2b) chronic hepatitis C patients with an HCV-RNA level of less than 100 Kcopies/mL (Amplicor Monitor) received 3 million units of IFN-β for 4 wk twice daily in the morning and evening, followed by 10 million units of IFN-α2b three times weekly for 14 wk. As a result, all of them became negative for HCV-RNA during treatment, and achieved an SVR rate of 82.4% or 14/17 (in Japanese)[25]. Asahina et al[13] measured HCV-RNA levels by real-time PCR for up to fourteen days of IFN-β treatment, and reported that HCV-RNA levels, except in a small number of null responders, declined in a biphasic manner, consisting of a first phase of several days followed by a second phase. The exponential decay slopes (Log10/d) of the first and second phases were 1.62 ± 0.81 and 0.02 ± 0.09*, respectively, in the case of a once-daily regimen, and 1.91 ± 0.57 and 0.16 ± 0.09*, respectively, in the case of a twice-daily regimen (*P = 0.0003). On the other hand, it was reported that the HCV-RNA levels (Log10 IU/mL, median, range) before and fourteen days after the initiation of Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy were 5.9 (5.37-6.34) and 4.93 (< 2.78-5.95), respectively, a decrease of approximately 1 Log IU/mL during the early phase of treatment[16], which clearly indicates that IFN-β is highly effective in reducing HCV-RNA levels.

Since the main subjective symptoms of side effects of IFN-β were fever and associated influenza-like symptoms, it was important to control fever. In contrast to persistently high titers of Peg-IFN in the blood, the T1/2 of IFN-β in the blood was short, at 15-43 min[26], and fever tended to occur within the first several hours after administration of IFN-β. Perhaps it was effective that the timing of IFN administration was arranged so that the blood level of loxoprofen became elevated during this time period. Laboratory abnormalities such as low platelet counts and proteinuria were noted, but they subsided or disappeared during Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy, presenting no problems.

The results of this study suggest the possibility of shortening the duration of Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C patients with a high viral load of genotype 1b virus by using an IFN-β induction regimen. Further clinical studies involving many more patients are needed to test this.

The standard treatment for chronic hepatitis C patients with a high viral load of the genotype-1b hepatitis C virus is 48 wk Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy. This therapy is more effective than the conventional IFN therapy, but side effects such as fever and general fatigue are problematical. Since early treatment discontinuation is associated with poor sustained virologic response (SVR) rates, physicians should encourage patients to complete the full course of therapy, and to endure these side effects.

The SVR rate of Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy for 24 wk is usually about 50%. Only when patients with an HCV-RNA level of < 400 000 IU/mL become negative for HCV-RNA after 4 wk of treatment (RVR), and they achieve an SVR rate of 84%-96% after 24 wk of treatment, are they eligible for the shortened treatment option. However, since only 15%-20% of the total patients, mainly consisting of those with a low viral load, achieve an RVR, the number of patients eligible for the shortened treatment schedule is limited.

It has been reported that the twice-daily administration of IFN-β in the morning and evening for 2 wk reduces HCV-RNA levels by an average of 3 Log IU/mL, except in a small number of null responders.

The SVR rate of chronic hepatitis C patients with a high viral load of genotype-1 hepatitis C virus receiving 2 wk IFN-β induction therapy followed by 20 to 24 wk Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy was 55%. Of these patients, 45% patients, with a pretreatment platelet count of ≥ 130 000/μL and a HCV-RNA level of < 3.3 Log IU/mL at the end of IFN-β treatment, achieved an SVR rate of 93%.

The duration of Peg-IFN plus RBV combination therapy can be shortened by actively reducing HCV-RNA levels through prior induction therapy.

The manuscript is somewhat interesting and the design is acceptable. Some changes must be performed before It can be accepted for publication after some changes are performed.

Peer reviewer: Ruben Ciria, PhD, Uniersity Hospital Reina Sofia, Departmento De Cirugia Hepatobiliar Y Trasplante HEPÁTICO (Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation), Avennida Menendez PidalI s/n, Cordoba 14004, Spain

| 1. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. |

| 2. | McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling MH, Cort S, Albrecht JK. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492. |

| 3. | McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Dienstag J, Lee WM, Mak C, Garaud JJ. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061-1069. |

| 4. | Shiffman ML, Ghany MG, Morgan TR, Wright EC, Everson GT, Lindsay KL, Lok AS, Bonkovsky HL, Di Bisceglie AM, Lee WM. Impact of reducing peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin dose during retreatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:103-112. |

| 5. | Jensen DM, Morgan TR, Marcellin P, Pockros PJ, Reddy KR, Hadziyannis SJ, Ferenci P, Ackrill AM, Willems B. Early identification of HCV genotype 1 patients responding to 24 weeks peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kd)/ribavirin therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:954-960. |

| 6. | Mangia A, Minerva N, Bacca D, Cozzolongo R, Ricci GL, Carretta V, Vinelli F, Scotto G, Montalto G, Romano M. Individualized treatment duration for hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:43-50. |

| 7. | Liu CH, Liu CJ, Lin CL, Liang CC, Hsu SJ, Yang SS, Hsu CS, Tseng TC, Wang CC, Lai MY. Pegylated interferon-alpha-2a plus ribavirin for treatment-naive Asian patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1260-1269. |

| 8. | Yu ML, Dai CY, Huang JF, Chiu CF, Yang YH, Hou NJ, Lee LP, Hsieh MY, Lin ZY, Chen SC. Rapid virological response and treatment duration for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:1884-1893. |

| 9. | Moreno C, Deltenre P, Pawlotsky JM, Henrion J, Adler M, Mathurin P. Shortened treatment duration in treatment-naive genotype 1 HCV patients with rapid virological response: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:25-31. |

| 10. | Ferenci P, Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Smith CI, Marinos G, Gonçales FL Jr, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Predicting sustained virological responses in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40 KD)/ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2005;43:425-433. |

| 11. | Ikeda F, Shimomura H, Miyake M, Fujioka SI, Itoh M, Takahashi A, Iwasaki Y, Sakaguchi K, Yamamoto K, Higashi T. Early clearance of circulating hepatitis C virus enhanced by induction therapy with twice-a-day intravenous injection of IFN-beta. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:831-836. |

| 12. | Shiratori Y, Perelson AS, Weinberger L, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O, Nakata R, Ihori M, Hirota K, Ono N, Kuroda H. Different turnover rate of hepatitis C virus clearance by different treatment regimen using interferon-beta. J Hepatol. 2000;33:313-322. |

| 13. | Asahina Y, Izumi N, Uchihara M, Noguchi O, Tsuchiya K, Hamano K, Kanazawa N, Itakura J, Miyake S, Sakai T. A potent antiviral effect on hepatitis C viral dynamics in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells during combination therapy with high-dose daily interferon alfa plus ribavirin and intravenous twice-daily treatment with interferon beta. Hepatology. 2001;34:377-384. |

| 14. | Nakajima H, Shimomura H, Iwasaki Y, Ikeda F, Umeoka F, Chengyu P, Taniguchi H, Ohnishi Y, Takagi SJ, Fujioka S. Anti-viral actions and viral dynamics in the early phase of three different regimens of interferon treatment for chronic hepatitis C: differences between the twice-daily administration of interferon-beta treatment and the combination therapy with interferon-alpha plus ribavirin. Acta Med Okayama. 2003;57:217-225. |

| 15. | Asahina Y, Izumi N, Uchihara M, Noguchi O, Nishimura Y, Inoue K, Ueda K, Tsuchiya K, Hamano K, Itakura J. Interferon-stimulated gene expression and hepatitis C viral dynamics during different interferon regimens. J Hepatol. 2003;39:421-427. |

| 16. | Herrmann E, Lee JH, Marinos G, Modi M, Zeuzem S. Effect of ribavirin on hepatitis C viral kinetics in patients treated with pegylated interferon. Hepatology. 2003;37:1351-1358. |

| 17. | Izumi N, Asahina Y, Kurosaki M, Uchihara M, Nishimura Y, Inoue K, Ueda K, Tsuchiya K, Hamano K, Itakura J. A comparison of the exponential decay slope between PEG-IFN alfa-2b/ribavirin and IFN alfa-2b/ribavirin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1b infection and a high viral load. Intervirology. 2004;47:102-107. |

| 18. | Kuboki M, Iino S, Okuno T, Omata M, Kiyosawa K, Kumada H, Hayashi N, Sakai T. Peginterferon alpha-2a (40 KD) plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:645-652. |

| 19. | Furusyo N, Kajiwara E, Takahashi K, Nomura H, Tanabe Y, Masumoto A, Maruyama T, Nakamuta M, Enjoji M, Azuma K. Association between the treatment length and cumulative dose of pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin and their effectiveness as a combination treatment for Japanese chronic hepatitis C patients: project of the Kyushu University Liver Disease Study Group. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1094-1104. |

| 20. | Kakizaki S, Takagi H, Yamada T, Ichikawa T, Abe T, Sohara N, Kosone T, Kaneko M, Takezawa J, Takayama H. Evaluation of twice-daily administration of interferon-beta for chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:315-319. |

| 21. | Yoshioka K, Yano M, Hirofuji H, Arao M, Kusakabe A, Sameshima Y, Kuriki J, Kurokawa S, Murase K, Ishikawa T. Randomized controlled trial of twice-a-day administration of natural interferon beta for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Res. 2000;18:310-319. |

| 22. | Shiratori Y, Nakata R, Shimizu N, Katada H, Hisamitsu S, Yasuda E, Matsumura M, Narita T, Kawada K, Omata M. High viral eradication with a daily 12-week natural interferon-beta treatment regimen in chronic hepatitis C patients with low viral load. IFN-beta Research Group. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:2414-2421. |

| 23. | Izumi N, Kumada H, Hashimoto N, Harada H, Imawari M, Zeniya M, Toda G. Rapid decrease of plasma HCV RNA in early phase of twice daily administration of 3 MU doses interferon-beta in patients with genotype 1b hepatitis C infection: a multicenter randomized study. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:516-523. |

| 24. | Okushin H, Morii K, Yuasa S. Efficacy of the combination therapy using twice-a-day IFN-beta for chronic hepatitis C. Kanzo. 1995;49:735. |

| 25. | Okushin H, Morii K, Kishi F, Yuasa S. Efficacy of the combination therapy using twice-a-day IFN-beta followed by IFN-alpha-2b in treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Kanzo. 1997;38:11-18. |

| 26. | Hino K, Kondo T, Yasuda K, Fukuhara A, Fujioka S, Shimoda K, Niwa H, Iino S, Suzuki H. Pharmacokinetics and biological effects of beta interferon by intravenous (iv) bolus administration in healthy volunteers as compared with iv infusion. Jpn J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;19:625-635. |