INTRODUCTION

The presence of hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) on computed tomography (CT) is typically an ominous finding that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. It is most commonly associated with bowel necrosis (72%), followed by ulcerative colitis (8%), intra-abdominal abscesses (6%), small bowel obstruction (3%) and gastric ulcers (3%)[1]. The frequent association with bowel necrosis can explain the 56%-90% mortality rate associated with HPVG[2].

We report a case of a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) who was found to have HPVG on CT as a presumed result of gastrointestinal Cryptosporidiosis. This association, to our knowledge, has never been reported.

CASE REPORT

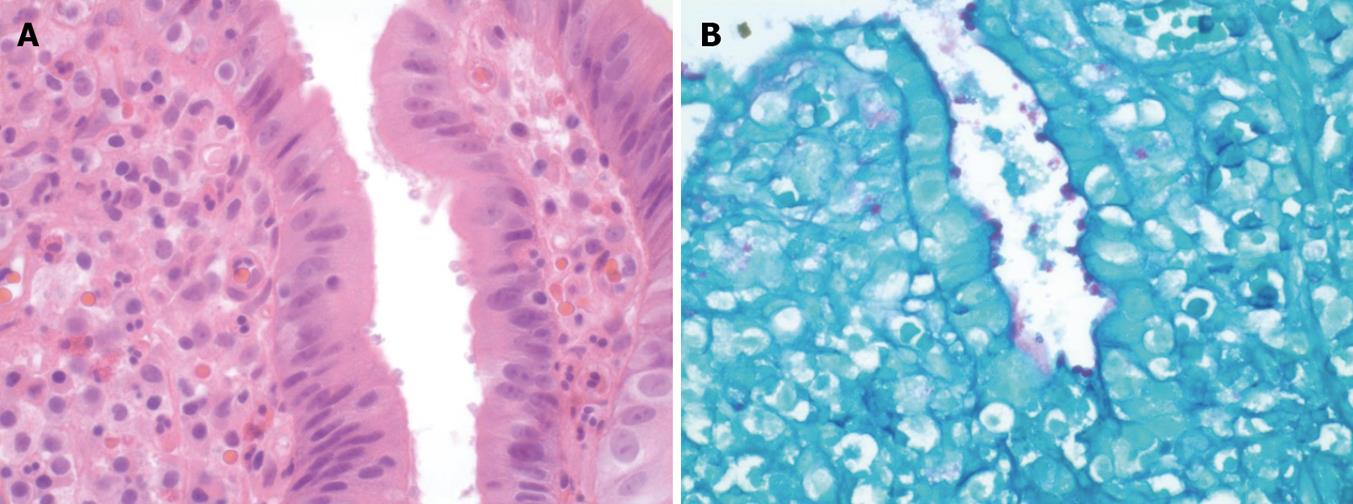

A 47-year-old African American female with a history of AIDS with a CD4 count of 12 (confirmed by repeated measurements) presented with diarrhea, dizziness, and fatigue over a period of three weeks. Her vitals on admission were as follows: temperature 37.3°C, heart rate 103/min, blood pressure 93/65 mmHg, and respiratory rate of 20/min. On physical exam she had diffuse mild abdominal pain, tachycardia, and poor skin turgor. Initial laboratory results: white blood cell (WBC) 6.4 k/μL, hemoglobin (Hb) 8.3 g/dL, platelets (PLT) 252 000/cc3, sodium 141 mmol/L, potassium 3.6 mmol/L, chloride 111 mmol/L, bicarbonate 22 mmol/L, BUN 14 mg/dL, creatinine 3.8 mg/dL, and glucose 100 mg/dL. Her baseline creatinine was less than 1.0 mg/dL. Stool studies for Clostridium Difficile, acid-fast bacilli, fecal leukocytes, culture, and ova and parasites were all negative. A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis did not show any acute findings. Colonoscopy was normal from the ileum to the rectum. Random biopsies were taken from the terminal ileum, colon, and rectum. The biopsy from the terminal ileum was identified as having numerous parasitic organisms morphologically consistent with Cryptosporidium Parvum (Figure 1A). The patient was discharged on a 7 d course of metronidazole with plans to start highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as an outpatient.

Figure 1 Cryptosporidium microorganisms shown by the biopsy.

A: On the surface epithelium of the terminal ileum; B: On the surface epithelium of the duodenum (Periodic acid schiff stain).

Prior to initiating HAART therapy, the patient returned one week later with profuse bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and oliguria. She was alert and oriented, but appeared weak. She had a temperature of 37.0°C, heart rate of 101/min, blood pressure 88/61 mmHg, and a respiratory rate of 18/min. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender with positive bowel sounds. Laboratory results: WBC 10.9 k/μL, Hb 11.6 gm/dL, PLT 250 000/cc3, sodium 135 mmol/dL, potassium 4.2 mmol/dL, chloride 109 mmol/dL, bicarbonate 9 mmol/dL, BUN 34 mg/dL, creatinine 13 mg/dL, and glucose 159 mg/dL. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase were normal. The albumin was 2.1 g/dL, with an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.24. She was admitted to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) for further management. Esophagastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed normal findings from the proximal esophagus to the antrum. The duodenum had a 3-mm submucosal nodule in the duodenal bulb and a 5-mm submucosal nodule in the duodenal apex. Biopsy of the duodenal nodules showed ulcerated, active chronic duodenitis with numerous organisms morphologically consistent with Cryptosporidium Parvum present in the epithelial surface; Periodic acid schiff (PAS) stain was positive (Figure 1B).

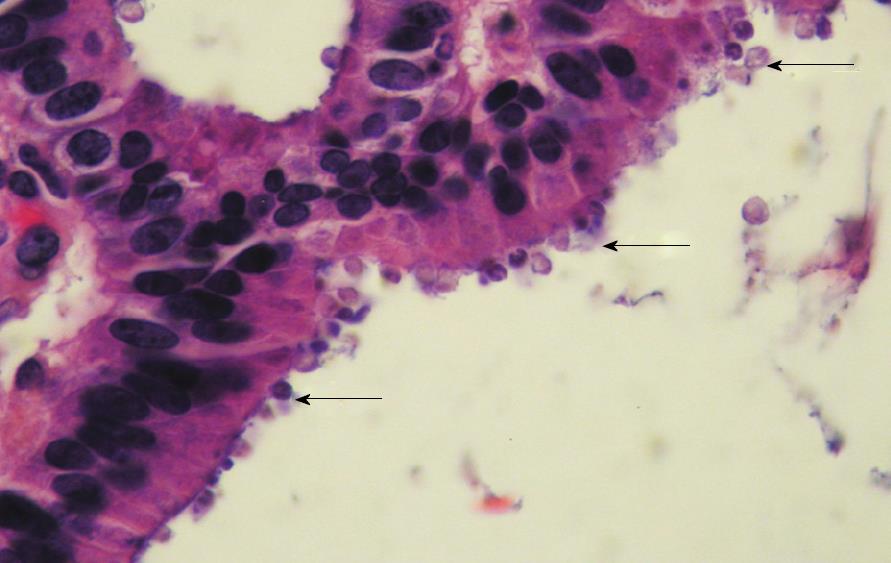

Several days into her admission, she continued to have hypotension, tachycardia, and vague abdominal pain. A non-contrast abdominal CT was repeated, which showed diffuse portal venous gas. In addition, there were small bubbles of gas distributed in a linear fashion in the anterior abdomen, along the transverse colon, likely within venous branches, although no definite evidence of pneumatosis intestinalis was seen. The remainder of the CT, including the gallbladder, appeared normal (Figure 2). After confirming these findings with two board-certified radiologists, the patient was taken immediately to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy. The entire small bowel, colon, and rectum appeared grossly normal. The gallbladder appeared distended and necrotic; it was therefore removed. Pathologically, the gallbladder showed Cryptosporidium Parvum (Figure 3). The patient had an uneventful post-operative course. However, given the advanced nature of her AIDS and her poor functional status, she was discharged home with hospice services eight days after surgery.

Figure 2 Non-contrast axial computed tomography of the upper abdomen demonstrates multiple peripheral linear branching air density structures consistent with portal venous air.

Figure 3 Gallbladder showing Cryptosporidium located on the surface of the epithelium.

DISCUSSION

HPVG occurs when intraluminal gas enters the porto-mesenteric venous circulation as a consequence of mucosal damage from bowel ischemia, inflammatory bowel disease, bowel distention, intra-abdominal infection, or peptic ulcer disease. In some instances, the proliferation of non-pathogenic gas-forming bacteria in the lumen can lead to the radiographic findings of pneumatosis intestinalis and subsequently HPVG. Similarly, increased intraluminal pressure during colonoscopy or intraperitoneal pressure associated with blunt trauma can also permit bowel gas to gain access to the portal venous circulation through microscopic mucosal injury[3-11].

Intra-abdominal infections associated with HPVG include diverticulitis, abdominal abscesses, cholycystitis, cholangitis, appendicitis, and colitis[4,12-15]. The pathogenesis of infectious HPVG is not fully understood. Some theories include septicemia in branches of the mesenteric and portal veins[16], increased carbohydrate fermentation due to bacteria in the intraluminal region, or a mesocolic abscess causing infra-mesocolic perforation, allowing gas to access to the portal vasculature[17]. Furthermore, the coexistence of a chronic disease, such as renal failure, diabetes mellitus or hypertension can predispose to HPVG by altering the intestinal microbial flora[18].

Cryptosporidium spp. is a major cause of gastrointestinal disease in both immunocompetent and immunodeficient individuals. Although these infections are typically self-limited in healthy individuals, they can have severe manifestations in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with AIDS[19]. When cryptosporidiosis presents as disseminated disease, there can be involvement of the small intestine, colon, biliary tract, pancreas, and the respiratory tract. Of patients with intestinal cryptosporidiosis, ten percent have biliary tract abnormalities[20-21]. The risk of fecal carriage, severity of illness, and development of severe complications of cryptosporidiosis are inversely related to the CD4 count[19]. Our patient had a CD4 count of 12, which placed her at a very high risk of complicated infection. To our knowledge, AIDS-related cryptosporidiosis as a cause for HPVG has not been reported.

In conclusion, the clinical significance of HPVG is variable, and it depends primarily on the underlying pathology. In the most severe conditions it can be the result of mesenteric ischemia; however, growing literature is showing that there are less catastrophic conditions in which HPVG may occur. We conclude that in a patient with AIDS, Cryptosporidium can cause HPVG. This case illustrates another cause of HPVG that should be considered in patients with AIDS.