Published online Feb 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i2.102375

Revised: December 6, 2024

Accepted: January 7, 2025

Published online: February 27, 2025

Processing time: 127 Days and 18.1 Hours

Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) is a rare autosomal recessive liver disease, causing episodic cholestasis with intense pruritus. This case report high

A 43-year-old male with BRIC type 2 presented with fatigue, jaundice, and severe pruritus, triggered by a recent mild severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavi

Plasmapheresis is a safe and effective option for therapy-refractory BRIC type 2, particularly when initiated early in cholestasis.

Core Tip: This case report highlights the successful use of early plasmapheresis in managing a patient with pruritus due to a cholestatic episode of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis type 2, triggered by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Plasmapheresis provided rapid relief from severe pruritus when first-line therapies failed and, when reinitiated early during a consequent flare, significantly accelerated recovery from cholestasis. While the procedure’s invasiveness and associated costs underscore the importance of careful patient selection, prompt initiation should be con

- Citation: Heyerick L, Dhondt A, Van Vlierberghe H, Verhelst X, Raevens S, Geerts A. Early plasmapheresis in type 2 benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis: A case report and review of literature. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(2): 102375

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i2/102375.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i2.102375

Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) is a group of rare inherited cholestatic liver diseases caused by autoso

Given its generally benign clinical course, the treatment of BRIC is symptomatic and supportive[6]. While most patients respond well to pharmacological or endoscopic therapies, some experience refractory symptoms that severely impair quality of life. Additional therapeutic options for these patients are highly required. This case report describes the successful use of plasmapheresis in a BRIC type 2 patient during a cholestatic episode, resulting in rapid symptomatic relief and improved biochemical parameters. Early reinitiation of plasmapheresis during a subsequent flare several years later resulted in quick resolution of the cholestatic episode.

A 43-year-old Caucasian male patient presented with fatigue, insomnia, and severe pruritus persisting for four weeks.

The patient's symptoms began three weeks after a mild severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, which did not require treatment. He reported worsening pruritus and jaundice, with no resolution of symptoms despite the use of antihistamines (levocetirizine 5 mg 2 times/day per os). His condition was further complicated by fatigue and sleep disturbances due to severe itching.

The patient was diagnosed with BRIC type 2 at the age of 22 years, confirmed by genotyping that revealed compound heterozygosity in the ABCB11 gene (p.E297G; p.I1227F). He had experienced multiple episodes of spontaneous, self-limiting cholestasis over the years. These episodes usually resolved within several months without progressing to liver cirrhosis or failure.

The patient had no significant personal or family history of liver disease outside his BRIC diagnosis. There was no family history of genetic liver disorders, and no close relatives had similar symptoms. The patient reported occasional alcohol use and had no history of smoking, drug or herbal (ab)use.

On examination, the patient was jaundiced but otherwise in a stable condition (blood pressure 17.7 kPa/10.3 kPa, regular heartbeat 88/minute, SpO2 98% on room air, temperature 36.3 °C). No abdominal tenderness, hepatosplenomegaly, or other abnormal physical findings were noted.

Laboratory results revealed significantly elevated total bilirubin (16.7 mg/dL) and direct bilirubin (14.3 mg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels were 2.9 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), while transaminases were mildly elevated (less than 1.5 × ULN). Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels were within normal limits. Other routine blood tests and urine analyses were unremarkable. There were no signs of active infection.

Abdominal ultrasound and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed no abnormalities in liver structure or biliary ducts, and no evidence of gallstones or liver masses.

A recurrent cholestatic flare in a patient with BRIC type 2, triggered by a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Initial management included cholestyramine (4 g 4 times/day per os) and rifampicin (150 mg 4 times/day per os), which proved ineffective in alleviating pruritus. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) was attempted but discontinued due to relapsing obstruction and lack of therapeutic benefit. As a third-line intervention, intermittent plasmapheresis was initiated six weeks after the onset of the cholestatic episode. Centrifugal apheresis (COM.TEC Fresenius-Kabi) was perfor

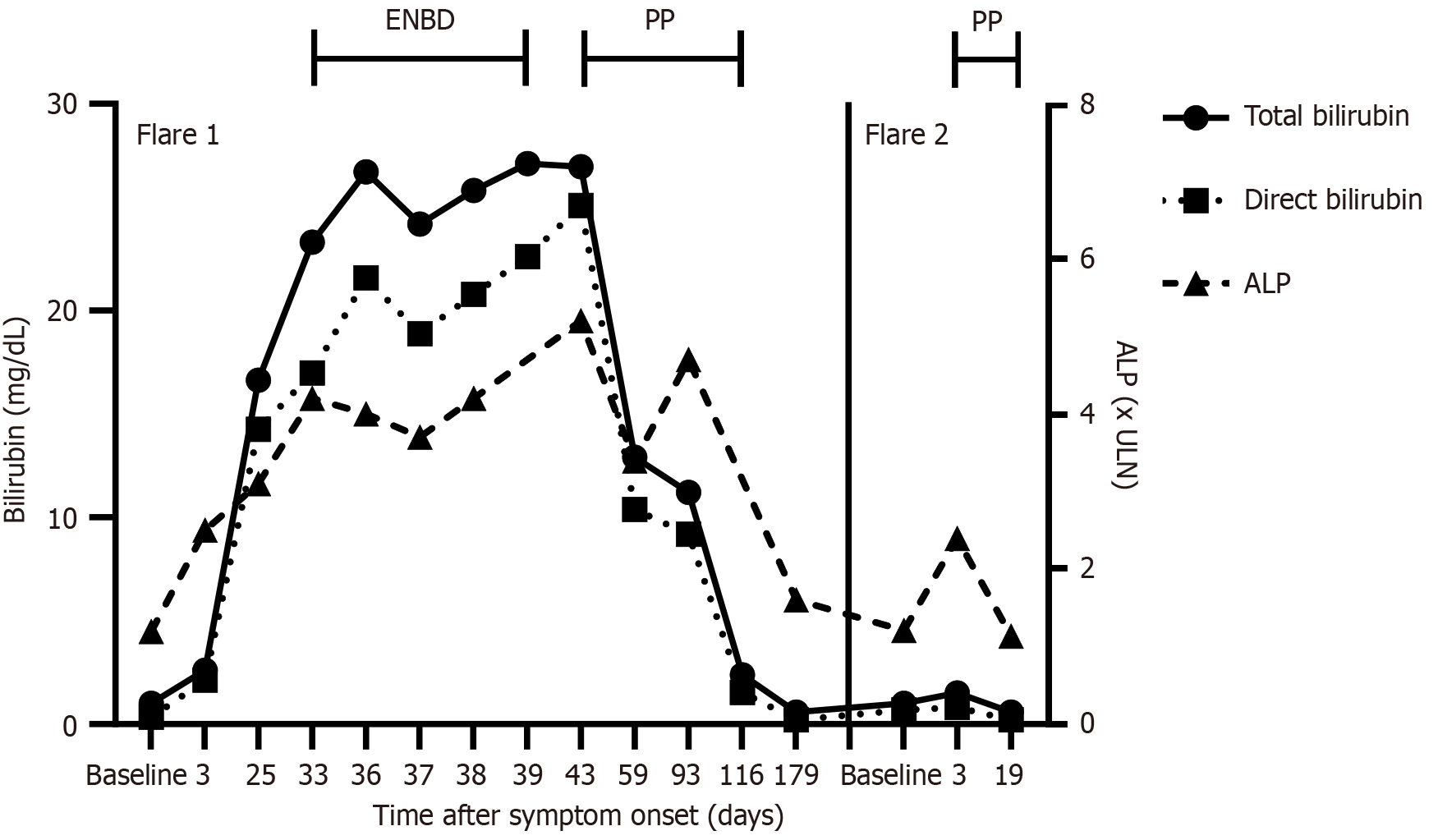

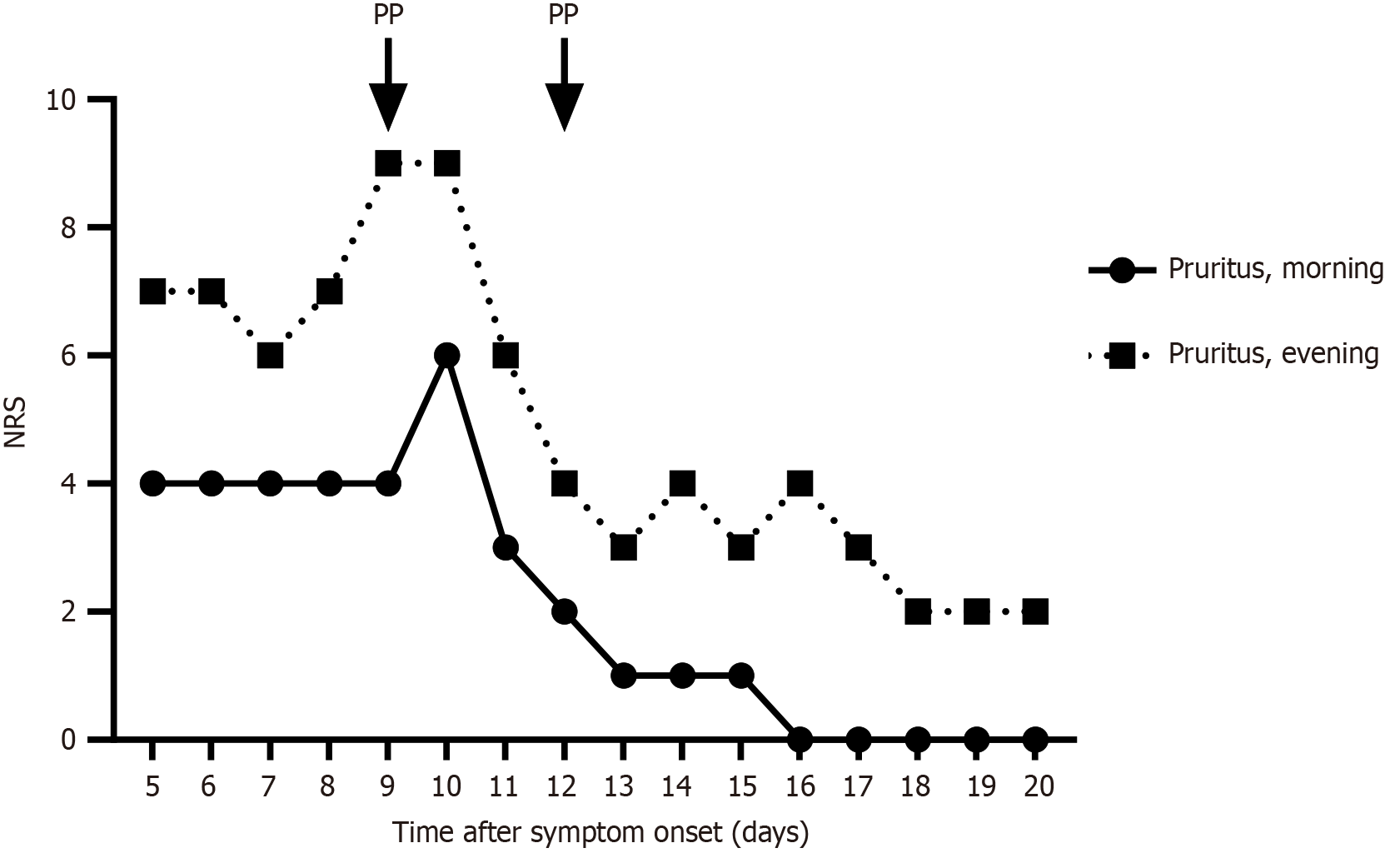

Two years after the first episode, following another mild SARS-CoV-2 infection, the patient experienced a new cholestatic episode marked by severe pruritus. Laboratory results showed early signs of cholestasis, including mildly elevated total bilirubin (1.5 mg/dL), direct bilirubin (0.8 mg/dL), and ALP (2.4 × ULN), while GGT levels remained normal. In between both episodes, the patient had been symptom-free with normal laboratory results. The patient refused pharmacological therapy and after shared decision-making, plasmapheresis was re-initiated early, within 10 days of symptom onset, using the same apheresis protocol. We asked the patient to track his mean pruritus levels on a numerical rating scale both in the morning and in the evening. As anticipated, reinitiation resulted in rapid amelioration of pruritus (Figure 2). Moreover, markers of cholestasis now also rapidly normalized, within two weeks of treatment initiation (Figure 1). Consequently, plasmapheresis could be discontinued after just two sessions. The patient remained symptom-free and there was no recurrence of cholestasis during further follow-up for more than one year.

This case report highlights the successful use of (early) plasmapheresis in managing a patient with therapy-refractory BRIC type 2. Notably, our findings underscore the potential of plasmapheresis not only to relieve symptoms but also to expedite recovery when initiated early during cholestatic episodes.

BRIC type 2 is a phenotype of an inherited cholestatic liver disease caused by genetic BSEP deficiency which disrupts hepatocanalicular bile salt transport. BRIC is generally considered a benign condition, as it typically does not progress to liver cirrhosis, although rare cases of progression to more severe cholestasis have been reported[7]. Consequently, treat

Among conventional treatments, rifampicin is most studied for BRIC-related pruritus, demonstrating moderate effi

Plasmapheresis proved to be an effective third-line intervention in this patient. The procedure involves the extracorporeal removal and replacement of plasma components, either with an albumin solution or with donor plasma[19]. Previous case reports have demonstrated similar results in therapy-refractory BRIC-associated pruritus[9,20-23] although not all patients respond uniformly[15]. Although it is an invasive procedure, the safety profile is favourable and reported side effects such as hypotension and hypofibrinogenemia are typically mild and correctable[19,24]. Our patient tolerated the procedure well, with no adverse effects observed. Our findings corroborate the potential utility of plasmapheresis as an effective and safe procedure. Similarly, its beneficial effects were also reported in other therapy-refractory cases of cholestatic liver disease such as intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy[25-27], primary biliary cholangitis[19,24,28,29] and drug-induced cholestasis[30-34].

Likewise, other extracorporeal elimination techniques, including liver dialysis systems such as the molecular adsorbent recirculating system and the Prometheus system, were reported to be effective in therapy-refractory pruritus in BRIC[35-37]. However, these methods are highly complex and have very limited availability, whereas plasmapheresis offers a simpler and more widely accessible alternative for extracorporeal elimination.

The mechanism behind the beneficial effects of plasmapheresis on pruritus are poorly understood, primarily because the pathogenesis of cholestatic pruritus itself is incompletely elucidated. Current evidence points to a role for autotaxin (ATX), a circulating lysophospholipase D that is responsible for the production of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)[38]. Serum levels of LPA and ATX are positively correlated with cholestatic pruritus intensity. Interestingly, plasmapheresis decreases ATX activity[25,39]. Also rifampicin directly interferes with the ATX pathway and decreases serum ATX levels[40]. However, the causative association of ATX and LPA to cholestatic itch is questioned and further research should unravel other factors that may play a more significant role in the pathogenesis of pruritus. Nevertheless, it seems that the beneficial effects of plasmapheresis are mediated by the removal of pruritogens that accumulate in the systemic circula

In BRIC specifically, the early initiation of plasmapheresis during a cholestatic flare appears to have additional benefits. During the second episode, we observed early recovery in our patient upon early reinitiation of plasmapheresis, an obser

While this case report provides compelling evidence for plasmapheresis as a treatment for therapy-refractory BRIC, the possibility that the early resolution of cholestasis during the second flare was due to an abortive attack[10] rather than the therapeutic effect of plasmapheresis cannot be excluded. Furthermore, its invasive nature and associated costs underscore the importance of careful patient selection. Nevertheless, the decision to initiate plasmapheresis should not be delayed in cases where pharmacological therapy and ENBD fail to improve pruritus, or in centres where ENBD is unavailable. Given the absence of studies directly comparing the efficacy of plasmapheresis with ENBD, further research is essential to delineate the role of plasmapheresis in the management of BRIC.

The management of cholestatic pruritus is advancing rapidly. Bezafibrate, a pan-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist, has recently been recommended as a first line therapy for adult patients with cholestatic pruritus[3,38]. However, its efficacy in the context of BSEP deficiency remains to be established. Odevixibat, an ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor that interferes with the reuptake of conjugated bile acids in the gut, has shown promising results in early randomized controlled trials for reducing pruritus in PFIC patients[45]. Additionally, chemical chaperones such as 4-phenylbutyrate (4-PB) provide the potential for mutation-specific therapy by correcting folding- and trafficking- deficient variants of the BSEP protein. Notably, 4-PB has demonstrated success in case reports involving patients with BRIC type 2[46-48].

Future research should prioritize understanding how therapeutic responses vary according to specific genetic mutations and their functional consequences. Given the genetic heterogeneity of BSEP deficiency, elucidating the rela

Plasmapheresis represents a promising option for treating therapy-refractory BRIC type 2. It is an effective, rapid-acting and safe procedure for achieving symptom relief and biochemical recovery. Furthermore, it is a potential accelerator of recovery when initiated early during a cholestatic episode. Given its invasiveness and associated costs, plasmapheresis should be reserved for patients unresponsive to first-line therapies, although initiation should not be delayed. As there are no direct comparative studies, the choice between plasmapheresis and ENBD should consider patient preferences, success of prior treatments, and local expertise.

| 1. | van Mil SW, van der Woerd WL, van der Brugge G, Sturm E, Jansen PL, Bull LN, van den Berg IE, Berger R, Houwen RH, Klomp LW. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis type 2 is caused by mutations in ABCB11. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:379-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kubitz R, Dröge C, Stindt J, Weissenberger K, Häussinger D. The bile salt export pump (BSEP) in health and disease. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:536-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on genetic cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2024;81:303-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Henkel SA, Squires JH, Ayers M, Ganoza A, Mckiernan P, Squires JE. Expanding etiology of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. World J Hepatol. 2019;11:450-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Halawi A, Ibrahim N, Bitar R. Triggers of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis and its pathophysiology: a review of literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2021;84:477-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van der Woerd WL, Houwen RH, van de Graaf SF. Current and future therapies for inherited cholestatic liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:763-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Ooteghem NA, Klomp LW, van Berge-Henegouwen GP, Houwen RH. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis progressing to progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis: low GGT cholestasis is a clinical continuum. J Hepatol. 2002;36:439-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kumagi T, Heathcote EJ. Successfully treated intractable pruritus with rifampin in a case of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2008;1:160-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Folvik G, Hilde O, Helge GO. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis: review and long-term follow-up of five cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:482-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Helgadottir H, Folvik G, Vesterhus M. Improvement of cholestatic episodes in patients with benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) treated with rifampicin. A long-term follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:512-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stapelbroek JM, van Erpecum KJ, Klomp LW, Houwen RH. Liver disease associated with canalicular transport defects: current and future therapies. J Hepatol. 2010;52:258-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Strubbe B, Geerts A, Van Vlierberghe H, Colle I. Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis and benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis: a review. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2012;75:405-410. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wakui N, Fujita M, Oba N, Yamauchi Y, Takeda Y, Ueki N, Otsuka T, Nishinakagawa S, Shiono S, Kojima T. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage improves jaundice attack symptoms in benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stapelbroek JM, van Erpecum KJ, Klomp LW, Venneman NG, Schwartz TP, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Devlin J, van Nieuwkerk CM, Knisely AS, Houwen RH. Nasobiliary drainage induces long-lasting remission in benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis. Hepatology. 2006;43:51-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yakar T, Demir M, Gokturk HS, Unler Kanat AG, Parlakgumus A, Ozer B, Serin E. Nasobiliary Drainage for Benign Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholestasis in Patients Refractory to Standard Therapy. Clin Invest Med. 2016;39:27522. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Choudhury A, Kulkarni AV, Sahoo B, Bihari C. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage: an effective treatment option for benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC). BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hegade VS, Krawczyk M, Kremer AE, Kuczka J, Gaouar F, Kuiper EM, van Buuren HR, Lammert F, Corpechot C, Jones DE. The safety and efficacy of nasobiliary drainage in the treatment of refractory cholestatic pruritus: a multicentre European study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:294-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Holz R, Kremer AE, Lütjohann D, Wasmuth HE, Lammert F, Krawczyk M. Can genetic testing guide the therapy of cholestatic pruritus? A case of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis type 2 with severe nasobiliary drainage-refractory itch. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Krawczyk M, Liebe R, Wasilewicz M, Wunsch E, Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Milkiewicz P. Plasmapheresis exerts a long-lasting antipruritic effect in severe cholestatic itch. Liver Int. 2017;37:743-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gao H, Lin S, Lv X, Ma H, Wang X, Fang J, Wu W, Lin J, Chen X, Lin M. The Identification of Two New ABCB11 Gene Mutations and the Treatment Outcome in a Young Adult with Benign Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholestasis: A Case Report. Hepat Mon. 2017;17. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sanderson F, Quaranta JF, Cassuto-Viguier E, Grimaldi C, Troin D, Dujardin P, Delmont J. [The value of plasma exchange during flare-ups of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis]. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1988;139 Suppl 1:35-37. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Brenard R, Geubel AP, Benhamou JP. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis. A report of 26 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:546-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nakad A, Geubel AP, Lejeune D, Delannoy A, Bosly A, Dive C. Plasmapheresis: an effective therapy for cholestatic episodes related to benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis? Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1988;139:128-130. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Chkheidze R, Joseph R, Burner J, Matevosyan K. Plasma exchange for the management of refractory pruritus of cholestasis: A report of three cases and review of literature. J Clin Apher. 2018;33:412-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ovadia C, Lövgren-Sandblom A, Edwards LA, Langedijk J, Geenes V, Chambers J, Cheng F, Clarke L, Begum S, Noori M, Pusey C, Padmagirison R, Agarwal S, Peerless J, Cheesman K, Heneghan M, Oude Elferink R, Patel VC, Marschall HU, Williamson C. Therapeutic plasma exchange as a novel treatment for severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Case series and mechanism of action. J Clin Apher. 2018;33:638-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Warren JE, Blaylock RC, Silver RM. Plasmapheresis for the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy refractory to medical treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:2088-2089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Covach AJ, Rose WN. Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy Refractory to Multiple Medical Therapies and Plasmapheresis. AJP Rep. 2017;7:e223-e225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alallam A, Barth D, Heathcote EJ. Role of plasmapheresis in the treatment of severe pruritus in pregnant patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: case reports. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:505-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cohen LB, Ambinder EP, Wolke AM, Field SP, Schaffner F. Role of plasmapheresis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 1985;26:291-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Miljić D, Stojanović M, Ješić R, Bogadnović G, Popović V. Role of plasma exchange in autoimmune hyperthyroidism complicated by severe tiamazol-induced cholestatic jaundice. Transfus Apher Sci. 2013;49:354-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chou JW, Yu CJ, Chuang PH, Lai HC, Hsu CH, Cheng KS, Peng CY, Chiang IP. Successful treatment of fosinopril-induced severe cholestatic jaundice with plasma exchange. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1887-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Qiao F, Chen Q, Lu W, Fang N. Plasma exchange treats severe intrahepatic cholestasis caused by dacomitinib: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Mongare N, Orare K, Busaidy S, Sokwala A, Opio C. Plasma Exchange for Refractory Pruritus Due to Drug-Induced Chronic Cholestasis Following Azithromycin Misuse in COVID-19 Infection. Cureus. 2024;16:e60884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Al-Azzawi H, Patel R, Sood G, Kapoor S. Plasmapheresis for Refractory Pruritus due to Drug-Induced Cholestasis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10:814-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ołdakowska-Jedynak U, Jankowska I, Hartleb M, Jirsa M, Pawłowska J, Czubkowski P, Krawczyk M. Treatment of pruritus with Prometheus dialysis and absorption system in a patient with benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:E304-E308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sturm E, Franssen CF, Gouw A, Staels B, Boverhof R, De Knegt RJ, Stellaard F, Bijleveld CM, Kuipers F. Extracorporal albumin dialysis (MARS) improves cholestasis and normalizes low apo A-I levels in a patient with benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC). Liver. 2002;22 Suppl 2:72-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Schoeneich K, Frimmel S, Koball S. Successful treatment of a patient with benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis type 1 with albumin dialysis. Artif Organs. 2020;44:341-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Beuers U, Wolters F, Oude Elferink RPJ. Mechanisms of pruritus in cholestasis: understanding and treating the itch. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:26-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Heerkens M, Dedden S, Scheepers H, Van Paassen P, Masclee A, de Die-Smulders C, Olde Damink SWM, Schaap FG, Jansen P, Koek G, Beuers U, Verbeek J. Effect of Plasmapheresis on Cholestatic Pruritus and Autotaxin Activity During Pregnancy. Hepatology. 2019;69:2707-2710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kremer AE, van Dijk R, Leckie P, Schaap FG, Kuiper EM, Mettang T, Reiners KS, Raap U, van Buuren HR, van Erpecum KJ, Davies NA, Rust C, Engert A, Jalan R, Oude Elferink RP, Beuers U. Serum autotaxin is increased in pruritus of cholestasis, but not of other origin, and responds to therapeutic interventions. Hepatology. 2012;56:1391-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Geier A, Dietrich CG, Voigt S, Ananthanarayanan M, Lammert F, Schmitz A, Trauner M, Wasmuth HE, Boraschi D, Balasubramaniyan N, Suchy FJ, Matern S, Gartung C. Cytokine-dependent regulation of hepatic organic anion transporter gene transactivators in mouse liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G831-G841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ashino T, Nakamura Y, Ohtaki H, Iwakura Y, Numazawa S. Interleukin-6 regulates the expression of hepatic canalicular efflux drug transporters after cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis: A comparison with lipopolysaccharide treatment. Toxicol Lett. 2023;374:40-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Donner MG, Schumacher S, Warskulat U, Heinemann J, Häussinger D. Obstructive cholestasis induces TNF-alpha- and IL-1 -mediated periportal downregulation of Bsep and zonal regulation of Ntcp, Oatp1a4, and Oatp1b2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1134-G1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Balagholi S, Dabbaghi R, Eshghi P, Mousavi SA, Heshmati F, Mohammadi S. Potential of therapeutic plasmapheresis in treatment of COVID-19 patients: Immunopathogenesis and coagulopathy. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59:102993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Thompson RJ, Arnell H, Artan R, Baumann U, Calvo PL, Czubkowski P, Dalgic B, D'Antiga L, Durmaz Ö, Fischler B, Gonzalès E, Grammatikopoulos T, Gupte G, Hardikar W, Houwen RHJ, Kamath BM, Karpen SJ, Kjems L, Lacaille F, Lachaux A, Lainka E, Mack CL, Mattsson JP, McKiernan P, Özen H, Rajwal SR, Roquelaure B, Shagrani M, Shteyer E, Soufi N, Sturm E, Tessier ME, Verkade HJ, Horn P. Odevixibat treatment in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:830-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Hayashi H, Naoi S, Hirose Y, Matsuzaka Y, Tanikawa K, Igarashi K, Nagasaka H, Kage M, Inui A, Kusuhara H. Successful treatment with 4-phenylbutyrate in a patient with benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis type 2 refractory to biliary drainage and bilirubin absorption. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:192-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sohail MI, Dönmez-Cakil Y, Szöllősi D, Stockner T, Chiba P. The Bile Salt Export Pump: Molecular Structure, Study Models and Small-Molecule Drugs for the Treatment of Inherited BSEP Deficiencies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sohn MJ, Woo MH, Seong MW, Park SS, Kang GH, Moon JS, Ko JS. Benign Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholestasis Type 2 in Siblings with Novel ABCB11 Mutations. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2019;22:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |