Published online Jan 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i1.100797

Revised: October 15, 2024

Accepted: November 18, 2024

Published online: January 27, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 19.6 Hours

Chylous ascites is an uncommon condition, occurring in less than 1% of ascites cases. It results from traumatic or obstructive disruption of the lymphatic system, causing the leakage of thoracic or intestinal lymph into the abdominal cavity. This leads to the accumulation of a milky, triglyceride-rich fluid. In adults, malignancy and cirrhosis are the primary causes of chylous ascites. Notably, chylous ascites accounts for only 0.5% to 1% of all cirrhosis-related ascites cases. At present, there is a limited understanding of this condition, and effective timely management in clinical practice remains challenging.

This case report presents a patient with hepatic cirrhosis complicated by chylous ascites, who had experienced multiple hospitalizations due to abdominal distension. Upon admission, comprehensive examinations and assessments were conducted. The treatment strategy focused on nutritional optimization through a low-sodium, low-fat, and high-protein diet supplemented with medium-chain triglycerides, therapeutic paracentesis, and diuretics. Following a multidisciplinary discussion and thorough evaluation of the patient’s condition, surgical indications were confirmed. After informing the patient about the benefits and risks, and obtaining consent, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure was performed, successfully alleviating the abdominal swelling symptoms. This article details the clinical characteristics and treatment approach for this uncommon case, summarizing current management methods for hepatic cirrhosis complicated by chylous ascites. The aim is to provide valuable insights for clinicians encountering similar situations.

Optimizing nutrition and addressing the underlying cause are essential in the treatment of chylous ascites. When conservative approaches prove ineffective, alternative interventions such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt may be considered.

Core Tip: This article presents a case of a patient with cirrhosis complicated by chylous ascites who experienced suboptimal outcomes despite adhering to conventional treatments, including a low-salt, low-fat, high-protein diet, diuretics, and abdominal paracentesis with catheter drainage. Ultimately, the patient’s condition was successfully managed through a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure. The treatment approach described in this case may provide valuable insights for managing similar cases in clinical practice.

- Citation: Chen ZQ, Zeng SJ, Xu C. Management of chylous ascites after liver cirrhosis: A case report. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(1): 100797

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i1/100797.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i1.100797

Chylous ascites is a relatively uncommon clinical condition[1], characterized by abdominal fluid rich in milky or creamy lipids, with abdominal distension as the primary clinical manifestation. Liver cirrhosis complicated by chylous ascites is even more rare, accounting for only 0.5% to 1% of all cases of cirrhosis-related ascites[2,3]. This report presents a case of hepatic cirrhosis with chylous ascites. The patient was admitted to our department multiple times between November 2017 and March 2023 due to bloating. During previous admissions, the patient showed improvement and was discharged after routine treatment, which included a low-salt, low-fat, high-protein diet, diuretics, and paracentesis. However, during the last hospitalization, the response to standard treatment was suboptimal, and the ascites transformed from clear to chylous. Ultimately, the patient’s condition improved following a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure. We utilize this opportunity to synthesize our findings with existing literature, aiming to enhance clinical awareness regarding the diagnosis and treatment of this condition and provide insights for clinical practice.

The patient, a 56-year-old male, was admitted on March 14, 2023, presenting with recurrent abdominal distension persisting for over 4 years, with the most recent episode lasting 10 days.

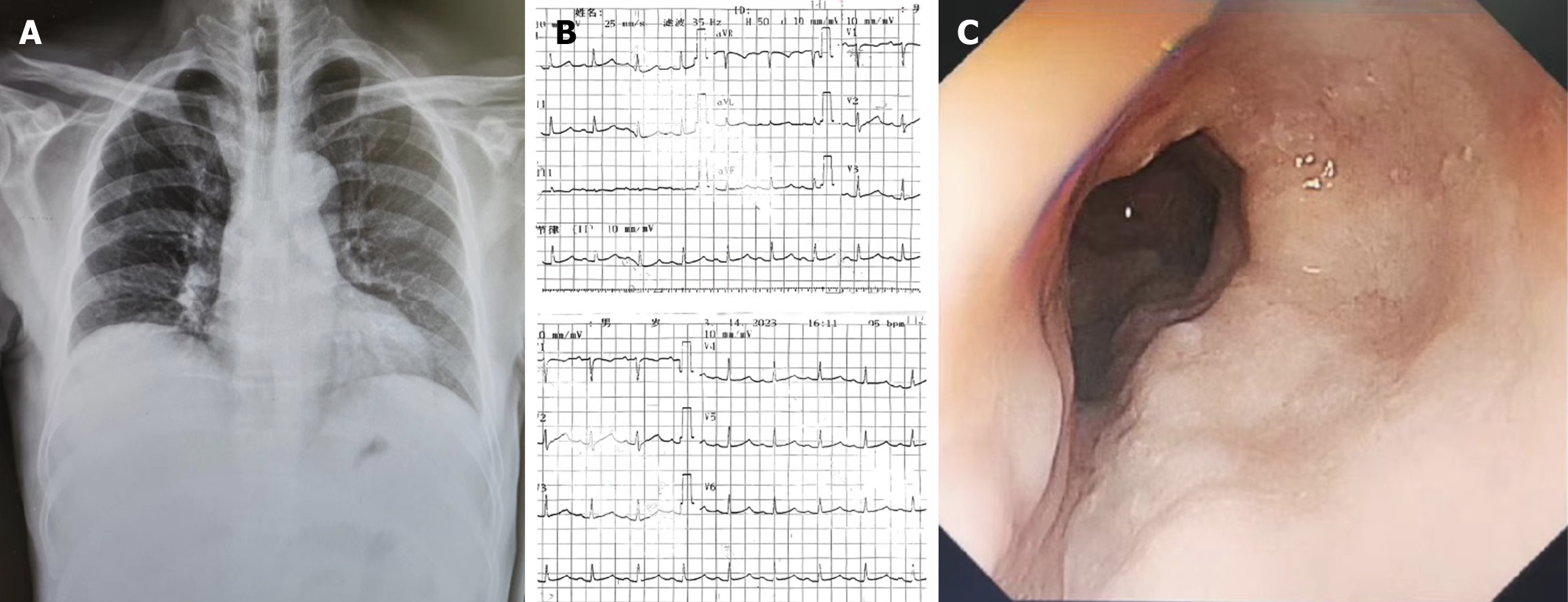

Initially, approximately four years ago, he experienced fatigue and weakness without apparent triggers, accompanied by reduced appetite and yellow urine. The patient reported no abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or other gastrointestinal symptoms. Neither jaundice of the skin nor sclera was observed, and both bowel movements and urine output remained normal. During hospitalization, comprehensive diagnostic tests were conducted, including complete blood count, urinalysis, stool analysis, liver and kidney function tests, chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, gastroscopy, and abdominal computed tomography. Considering the patient’s history of alcohol consumption (spanning over 30 years, with a daily intake of approximately 150 mL of liquor exceeding 40% alcohol content), he was diagnosed with de

The patient presents with a 10-year history of hepatitis B. In 2020, he underwent endoscopic interventions, including tissue glue and sclerotherapy injections, as well as band ligation, to address esophagogastric varices resulting from liver cirrhosis. Currently, the patient adheres to a regular antiviral regimen with tenofovir 25 mg. Additionally, he has managed diabetes for a decade, utilizing insulin aspart (8 IU subcutaneously before meals) and detemir insulin (8 IU subcutaneously at bedtime), maintaining fasting blood glucose levels within the range of 5-8 mmol/L.

The patient’s history includes prolonged alcohol consumption spanning over 30 years, with an average daily intake of 150 mL of liquor, and a 40-year smoking habit, averaging 10 cigarettes per day. His family consists of one son and three daughters, all reported to be in good health. No other significant medical information is noteworthy.

Upon admission, the physical examination revealed the following: The patient was alert and responsive, demonstrating normal cognitive function. Characteristic signs of chronic liver disease were evident, including severe jaundice affecting both skin and mucous membranes, as well as palmar erythema. The abdomen appeared distended with visible abdominal wall veins, and splenomegaly was noted, extending 2 cm below the rib cage, without associated tenderness. Shifting dullness was present, indicative of ascites. Notably, there was an absence of edema in the lower extremities. All other physical examination findings not explicitly mentioned were within normal limits.

The admission examination was on March 14, 2023: (1) Complete blood count: Hemoglobin (101 g/L), red blood cells (2.48 × 1012/L), mean corpuscular volume (112.9 fL), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (40.7 pg), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (361 g/L), white blood cells (2.9 × 109/L), neutrophil (2.14 × 109/L), lymphocyte (0.37 × 109/L), monocytes (0.33 × 109/L), eosinophilia (0.041 × 109/L), basophilia (0.02 × 109/L), platelet count (43 × 109/L); (2) Coagulation tests: Prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (1.38), prothrombin time (16.9 seconds), activated partial thromboplastin time (34.8 seconds), fibrinogen (2.03 g/L), thrombin time (22.1 seconds), D-Dimer (7530 ng/mL); (3) Comprehensive biochemical tests: Glucose (19.10 mmol/L), sodium (130 mmol/L), chloride (98.0 mmol/L), kalium (5.11 mmol/L), calcium (2.05 mmol/L), total CO2 (20.8 mmol/L), creatine kinase (138 U/L), creatine kinase-MB (51 U/L), apolipoprotein A (0.82 g/L), apolipoprotein B (0.69 g/L), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (0.78 mmol/L), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (1.66 mmol/L), cholesterol (3.20 mmol/L), triglyceride (1.75 mmol/L), lipoprotein(a) (0.003 g/L), uric acid (523 μmol/L), urea (3.80 mmol/L), creat (95 μmol/L), serum amylase (143 U/L), total protein (75.8 g/L), prealbumin (0.092 g/L), albumin (29.5 g/L), globulin (46.30 g/L), albumin/globulin (0.64), total bilirubin (50.6 μmol/L), direct bilirubin (39.4 μmol/L), alanine amiotransferase (22 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (74 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase/alkaline phosphatase (3.36), alkaline phosphatase (82 U/L), γ-glutamyl transpeptadase (349 U/L), cholinesterase (2947 U/L), lactate dehydrogenase (353 U/L), α-hydroxybutyric dehydrogenase (269 U/L), total biliary acid (47.9 μmol/L), adenosine deaminase (45.0 U/L); (4) Blood ammonia: 66.9 μmol/L; (5) C-reactive protein: 16.07 mg/L; (6) Hemoglobin A1c: 7.4%; (7) Abdominal fluid cholesterol (20.11 mg/dL), while triglyceride levels (136.35 mg/dL); and (8) Chylous test: Positive.

Abdominal computed tomography suggests the presence of cirrhosis with associated ascites (Figure 1).

Gastrointestinal surgery consultation recommendations: The patient’s medical history has been thoroughly evaluated. Based on the comprehensive assessment of the patient’s history and current diagnostic test results, a definitive diagnosis of cirrhosis with ascites has been established. The recommended treatment regimen includes albumin supplementation, diuretic therapy, and the administration of somatostatin.

Interventional radiology consultation recommendations: Upon review of the patient’s medical history, a comprehensive diagnosis has been established, including active cirrhosis (attributed to hepatitis B and alcohol consumption), decompensated stage, portal hypertensive gastropathy, splenomegaly, hypersplenism, and ascites. The clinical presentation indicates a clear necessity for interventional treatment. Subject to the patient’s and family’s informed consent, transfer to our department for an elective TIPS procedure is recommended. This intervention aims to reduce portal pressure and alleviate ascites.

Anesthesiology consultation recommendations: The patient’s medical history is thoroughly documented. The patient has a history of cirrhosis and underwent endoscopic tissue glue and sclerotherapy injections with band ligation in 2020. Based on the current examination and test results, the patient faces substantial anesthesia and surgical risks. It is advised to inform the patient of these risks preoperatively, address thrombocytopenia, and implement enhanced monitoring during and after the surgical procedure.

Final diagnosis as follows: (1) Active cirrhosis (hepatitis B and alcohol-related), decompensated stage, portal hypertensive gastropathy, splenomegaly, hypersplenism, and chylous ascites; (2) Moderate esophagogastric varices; (3) Post-treatment for esophagogastric varices; (4) Multiple nodules in liver segments S4 and S5; (5) Chronic superficial gastritis with raised erosions; (6) Type 2 diabetes; (7) Hypoalbuminemia; (8) Mild anemia; (9) Gallstones with cholecystitis; and (10) Left renal cyst.

In addition to the aforementioned tests, we conducted a chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, gastroscopy, and additional assessments to comprehensively evaluate the patient’s condition (Figure 2). Regarding treatment, the patient had previously undergone multiple hospitalizations and received various internal medicine therapies. These included sodium and water restriction, combined administration of potassium-sparing and potassium-depleting diuretics, albumin supplementation, and abdominal paracentesis drainage. These interventions initially resulted in the amelioration of the patient’s ascites symptoms. However, during the patient’s most recent hospitalization, the response to the aforementioned conventional treatments was suboptimal. The specific treatment regimen consisted of: Tenofovir 25 mg orally once daily, furosemide 20 mg orally twice daily, spironolactone 100 mg orally once daily, potassium chloride sustained-release tablets 1 g orally twice daily, lansoprazole enteric-coated tablets 30 mg orally once daily, lactobacillus enteric-coated capsules 0.66 g orally three times daily, bacillus licheniformis capsule (live) 0.25 g orally three times daily, and ademetionine 1,4-butanedisulfonate enteric-coated tablets 0.5 g once daily. The treatment regimen included latamoxef 1 g administered intravenously every 12 hours, human albumin 10 g administered intravenously daily, and abdominal puncture drainage resulting in 1000 mL of fluid drained daily. Furthermore, platelet transfusions were requested to mitigate potential risks. The patient persistently experienced significant ascites drainage daily, initially presenting as pale-yellow serous fluid, which subsequently transformed into chylous ascites (Figure 3). Following consultation with the gastroenterology, interventional radiology, and anesthesiology teams and conducting a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s condition, we informed the patient about the risks and benefits of TIPS. The patient was subsequently discharged with symptomatic improvement after undergoing TIPS (Figure 4).

The patient was discharged from the hospital with regular medication and regular follow-ups, with no significant deterioration in liver function and no significant worsening of abdominal distension.

Chylous ascites can arise from various etiologies, with its pathogenesis involving congenital or secondary factors that lead to lymphatic leakage or rupture, resulting in chyle accumulation within the abdominal cavity. Congenital factors, more frequently observed in children, may include lymphatic malformation, constriction, or dilation. Secondary factors, such as tumors, cirrhosis, and trauma, can induce lymphatic leakage or rupture, causing chyle to enter the abdominal cavity[4]. In a study by Vasko and Tapper[5], 140 cases of chylous ascites were reported, comprising 81 adult cases and 59 pediatric cases. The primary etiologies in adults encompass malignant tumors, cirrhosis, surgical procedures, and infections, while lymphatic anomalies predominate in minors. Cirrhosis-induced chylous ascites is attributed to portal hypertension, increased hepatic lymph flow, elevated lymphatic pressure, and subsequent leakage or rupture of small lymphatic vessels, culminating in chylous ascites formation[6-8].

Cirrhosis-related chylous ascites is an uncommon clinical presentation. Press et al[9] reported that approximately one in 20000 hospitalized patients experienced cirrhosis complicated by chylous ascites over a 20-year period. In China, a study at Peking Union Medical College Hospital documented 27 cases of chylous ascites among 461316 inpatients between 1923 and 1994, representing about 6 per 100000 cases. Additional research indicates that chylous ascites constitutes only 0.5%-1% of ascites cases in cirrhosis and is associated with poor prognosis[2,10]. Furthermore, the transition from clear to chylous ascites signifies an unfavorable progression. In the present case, the transformation of ascites from clear to chylous and the markedly reduced intervals between hospitalizations indicate disease advancement (Table 1). This progression may be attributed to worsening cirrhosis and elevated portal vein pressure. Concurrently, we have compiled the patient’s liver function test results from multiple hospital admissions (Table 2).

| Date | Color | Transparency | TP (g/L) | ADA (U/L) | Rivalta test | WBC (× 106/L) | LDH (U/L) | Glu (mmol/L) |

| November 6, 2017 | Yellow | Cloudy | 22.6 | 5 | Negative | 870 | 10582 | 19.39 |

| December 25, 2018 | Yellow | Cloudy | 11.3 | 3 | Negative | 244 | 56 | 8.44 |

| September 7, 2021 | Yellow | Cloudy | 15.3 | 3 | Negative | 243 | 83 | 10.51 |

| February 18, 2022 | Yellow | Cloudy | 15.7 | 4 | Negative | 2137 | 91 | 10.08 |

| June 18, 2022 | Red | Cloudy | 26.3 | 16 | Positive | 1233 | 131 | 15.79 |

| November 8, 2022 | Yellow | Cloudy | 16 | 4 | Positive | 253 | 61 | 13.2 |

| March 14, 2023 | Yellow | Cloudy | 14.5 | 2 | Negative | 82 | 65 | 10.65 |

| March 26, 2023 | Milky | Cloudy | 12.8 | 2 | Negative | 184 | 54 | 14.34 |

| Date | TBIL (μmol/L) | ALB (g/L) | PT (seconds) | Ascites | Hepatic encephalopathy | Child-Pugh classification |

| November 6, 2017 | 100.1 | 29 | 14.7 | Mild | No | B |

| December 25, 2018 | 20 | 33 | 13.6 | Severe | No | B |

| September 7, 2021 | 83 | 30.9 | 19.8 | Severe | No | C |

| February 18, 2022 | 67.3 | 25.7 | 16.5 | Severe | No | C |

| June 18, 2022 | 81.3 | 29.6 | 15.6 | Severe | No | C |

| November 8, 2022 | 116 | 31.4 | 17.8 | Severe | No | C |

| March 14, 2023 | 50.6 | 29.5 | 16.9 | Severe | No | C |

The diagnosis of chylous ascites can be established through prompt and precise evaluation of ascitic fluid, with diagnostic criteria typically involving a triglyceride level exceeding 200 mg/dL. Lymphoscintigraphy and lymphangiography can provide additional confirmation[11]. A study indicated that lymphangiography can identify the site of leakage in up to 79% of cases[12]. Lymphangiography is considered to offer superior clarity in depicting lymphatic system structural abnormalities and the location of lymphatic leakage compared to lymphoscintigraphy[13,14]. In our case, despite the ascitic fluid analysis showing cholesterol at 20.11 mg/dL and triglycerides at 136.35 mg/dL, the exclusion of abdominal surgical procedures, tumors, tuberculosis, and filariasis, combined with a positive chylous test, supports the validity of the chylous ascites diagnosis.

The primary management strategy for cirrhosis complicated by chylous ascites currently involves conservative treatment, with a focus on dietary therapy. This approach emphasizes a low-fat, low-sodium, high-protein diet. The rationale for this dietary recommendation stems from the distinct absorption pathways of different fatty acids. Long-chain triglycerides are predominantly absorbed via the gastrointestinal lymphatics, while short-chain and medium-chain fatty acids are directly absorbed into the portal venous system following intestinal absorption. Consequently, the consumption of short and medium-chain triglycerides is recommended[15].

Furthermore, medications play a crucial role in managing chylous ascites. Orlistat, a potent and long-acting gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor, reduces triglyceride absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby decreasing chyle production in ascites. Terlipressin, somatostatin, and their analogs, such as octreotide, effectively reduce portal vein pressure and are valuable treatments for chylous ascites[16,17]. Terlipressin administration for 5 days to 2 weeks can result in significant reduction or disappearance of ascites[18]. Therapeutic paracentesis combined with albumin supplementation for volume expansion is essential for rapid relief of patient discomfort and ascites elimination. Surgical interventions include interventional procedures, microsurgery, and peritoneovenous shunts. For cirrhotic patients unresponsive to medical therapy, surgical options may be considered. TIPS represents a significant advancement in cirrhosis management and has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in patients resistant to conservative treatments. It is indicated for patients with liver cirrhosis who have refractory ascites or require treatment or prevention of variceal bleeding. The patient does not have any contraindications, such as severe congestive heart failure (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stage C or D), severe untreated valvular heart disease (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stage C or D), hepatic encephalopathy, biliary obstruction, or liver lesions (like cysts) or tumors that would affect the establishment of the TIPS shunt[19]. It treats chylous ascites in liver cirrhosis by creating a shunt between the portal and systemic circulation, which reduces portal pressure and fluid accumulation. Compared to other treatments like diuretics and paracentesis, TIPS offers longer-lasting relief by addressing the underlying cause of fluid retention. Additionally, when compared to surgical procedures such as abdominal shunt surgery, TIPS is less invasive, has a shorter recovery time, and carries a lower risk of infection.

Cirrhosis complicated by chylous ascites represents an uncommon clinical presentation. Diagnostic approaches include ascites examination, lymphoscintigraphy, and lymphangiography. The primary treatment modality involves conservative measures, encompassing dietary modifications and pharmacological interventions. In cases where conventional therapies prove ineffective, TIPS may serve as a safe and efficacious alternative.

| 1. | Lizaola B, Bonder A, Trivedi HD, Tapper EB, Cardenas A. Review article: the diagnostic approach and current management of chylous ascites. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:816-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rector WG Jr. Spontaneous chylous ascites of cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:369-372. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Almakdisi T, Massoud S, Makdisi G. Lymphomas and chylous ascites: review of the literature. Oncologist. 2005;10:632-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Browse NL, Wilson NM, Russo F, al-Hassan H, Allen DR. Aetiology and treatment of chylous ascites. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1145-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vasko JS, Tapper RI. The surgical significance of chylous ascites. Arch Surg. 1967;95:355-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gidaagaya S, Hu JT, Chen DS, Yang SS. Acute rhabdomyolysis and chylous ascites in a patient with cirrhosis and malignant hepatic tumor. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:137-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Romero S, Martín C, Hernandez L, Verdu J, Trigo C, Perez-Mateo M, Alemany L. Chylothorax in cirrhosis of the liver: analysis of its frequency and clinical characteristics. Chest. 1998;114:154-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kumar R, Anand U, Priyadarshi RN. Lymphatic dysfunction in advanced cirrhosis: Contextual perspective and clinical implications. World J Hepatol. 2021;13:300-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Press OW, Press NO, Kaufman SD. Evaluation and management of chylous ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsauo J, Shin JH, Han K, Yoon HK, Ko GY, Ko HK, Gwon DI. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt for the Treatment of Chylothorax and Chylous Ascites in Cirrhosis: A Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:112-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cárdenas A, Chopra S. Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1896-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alejandre-Lafont E, Krompiec C, Rau WS, Krombach GA. Effectiveness of therapeutic lymphography on lymphatic leakage. Acta Radiol. 2011;52:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Archimandritis AJ, Zonios DI, Karadima D, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Kiriaki D, Hatzis GS. Gross chylous ascites in cirrhosis with massive portal vein thrombosis: diagnostic value of lymphoscintigraphy. A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Deso S, Ludwig B, Kabutey NK, Kim D, Guermazi A. Lymphangiography in the diagnosis and localization of various chyle leaks. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:117-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Collard JM, Laterre PF, Boemer F, Reynaert M, Ponlot R. Conservative treatment of postsurgical lymphatic leaks with somatostatin-14. Chest. 2000;117:902-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bai Z, An Y, Guo X, Teschke R, Méndez-Sánchez N, Li H, Qi X. Role of Terlipressin in Cirrhotic Patients with Ascites and without Hepatorenal Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;2020:5106958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Berzigotti A, Magalotti D, Cocci C, Angeloni L, Pironi L, Zoli M. Octreotide in the outpatient therapy of cirrhotic chylous ascites: a case report. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:138-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhou DX, Zhou HB, Wang Q, Zou SS, Wang H, Hu HP. The effectiveness of the treatment of octreotide on chylous ascites after liver cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1783-1788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee HL, Lee SW. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with portal hypertension: Advantages and pitfalls. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:121-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |