Published online Sep 27, 2024. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v16.i9.1297

Revised: August 22, 2024

Accepted: August 28, 2024

Published online: September 27, 2024

Processing time: 181 Days and 22.8 Hours

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), characterized by acute neurological deterioration and extensive white matter lesions on T2-fluid atten

This report describes three cases of liver transplant recipients who developed PRES. The first case involves a 60-year-old woman who experienced seizures, aphasia, and hemiplegia on postoperative day (POD) 9, with MRI revealing ischemic foci followed by extensive white matter lesions. After replacing tacro

Clinical manifestations, combined with characteristic MRI findings, are crucial in diagnosing PRES among organ transplant recipients. However, when standard treatments are ineffective or MRI results are atypical, alternative diagnoses should be taken into considered.

Core Tip: Liver transplantation is the only curative option for end-stage liver disease. The rise in liver transplants is accompanied by an increase in the occurrence of neurological complications. The etiology of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-related posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) remains unclear, and there are no established preventive measures. Optimal treatment strategies are still a matter of debate. CNIs, although widely used in liver transplants, come with various side effects. Therefore, when new neurological symptoms arise in liver transplant patients on CNIs who meet the diagnostic criteria for PRES, a cerebral magnetic resonance imaging should be promptly conducted to provide diagnostic evidence. Initiating treatment promptly upon confirming the diagnosis is essential for enhancing clinical outcomes.

- Citation: Gong Y. Calcineurin inhibitors-related posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in liver transplant recipients: Three case reports and review of literature. World J Hepatol 2024; 16(9): 1297-1307

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v16/i9/1297.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v16.i9.1297

Complications affecting the central nervous system, such as headaches, seizures, altered mental status, hemiplegia, sensory dysfunction, and visual impairments, frequently occur following solid organ transplantation. These complications are primarily caused by infections, the neurotoxic effects of immunosuppressive agents, and metabolic dis

Previous studies have suggested that neurotoxicity related to calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) occurs in an estimated 1% to 4% of solid organ transplant recipients[2,13,14]. While neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity are significant adverse effects of immunosuppressive drugs[15-17], the pathophysiology of CNI-related PRES remains a subject of debate. Some researchers propose that it is linked to vasogenic edema and dysregulation of cerebral blood flow, particularly within the posterior cerebral circulation[8,15]. As a result, reversible subcortical white matter lesions, primarily in the posterior cortex of the cerebral hemisphere, typically appear on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) within one to three months after organ transplantation. These lesions indicate a dysfunction in the regulation of the posterior cerebral circulation.

In 1996, Hinchey et al[16] first reported that CNIs could cause PRES. A retrospective analysis[18] involving 4222 solid organ transplant recipients found that the incidence of PRES was 0.49%. In this report, we present three cases of female liver transplant recipients diagnosed with CNI-related PRES, all of whom experienced favorable clinical outcomes. Additionally, we have summarized the clinical features of PRES through a literature review.

Case 1: A patient experienced a single episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding six months ago, following a diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis in 2010.

Case 2: A patient was diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis in 2014, which was complicated by cirrhosis with decompensation, recurrent abdominal distension, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Case 3: A patient presents with a chief complaint of having discovered a liver mass 3 months ago.

Case 1: The patient was admitted to the hospital on June 16, 2016, and underwent orthotopic liver transplantation at the Hepatic Surgery Department of Zhongshan Hospital affiliated with Fudan University. Post-surgery, her postoperative immunosuppressive regimen consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and methylprednisolone, with maintenance of tacrolimus trough levels between eight to ten ng/mL.

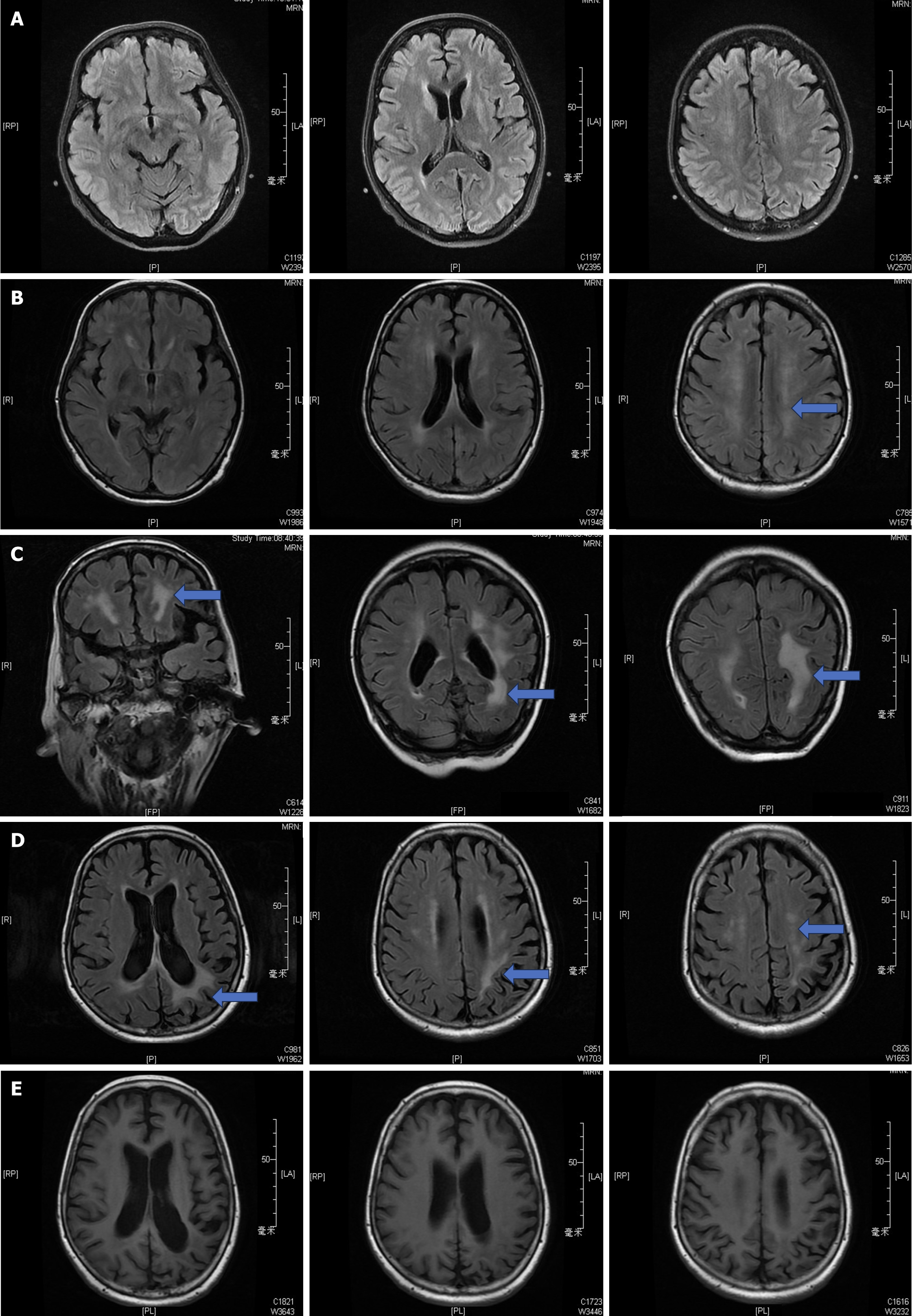

On June 15th, 2016 [postoperative day (POD) 9], the patient suddenly developed neurological symptoms, including seizures and episodes of staring spells accompanied by aphasia, which eventually led to hemiplegia affecting the left limb and loss of consciousness. A cerebral hemorrhage was ruled out based on cranial computed tomography (CT) findings, while the initial cranial MRI revealed ischemic foci localized within the bilateral frontal lobes, with no significant involvement of the white matter regions (Figure 1A).

Subsequent laboratory investigations, including serological assays and electroencephalographic studies, returned unremarkable results, leading to the initiation of antiepileptic therapy with levetiracetam, clonazepam, and alprostadil, along with adjunctive neuroprotective agents. Despite these interventions, there was no significant improvement. Follow-up cranial MRIs conducted on POD22 revealed a continuous linear area of hyperintense abnormal signals involving the left posterior parietal region on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), along with patchy hyperintensities in the periventricular white matter and pontine areas bilaterally, as seen on fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences (Figure 1B).

Consequently, the possibility of CNIs-associated PRES was considered, leading to a transition in the immunosuppressive regimen from tacrolimus to rapamycin, with high-dose methylprednisolone totaling 1680 milligrams administered. This resulted in a favorable response regarding clinical symptoms. Subsequent evaluation with a third cranial MRI performed on POD66 demonstrated persistent aberrant signaling confined to the periventricular regions, displaying hypointensity during T1-weighted imaging and slight hyperintensity during T2-weighted imaging (Figure 1C).

Case 2: The patient was admitted to the hospital on July 19th, 2022, and underwent orthotopic liver transplantation at Zhongshan Hospital affiliated with Fudan University. Her postoperative immunosuppression regimen included tacrolimus, mycophenolic acid, and methylprednisolone, with the tacrolimus trough concentration maintained between 8 and 10 ng/mL. Although her liver function recovered rapidly and her blood electrolyte levels remained relatively stable, her blood pressure consistently remained elevated at approximately 160/90 mmHg.

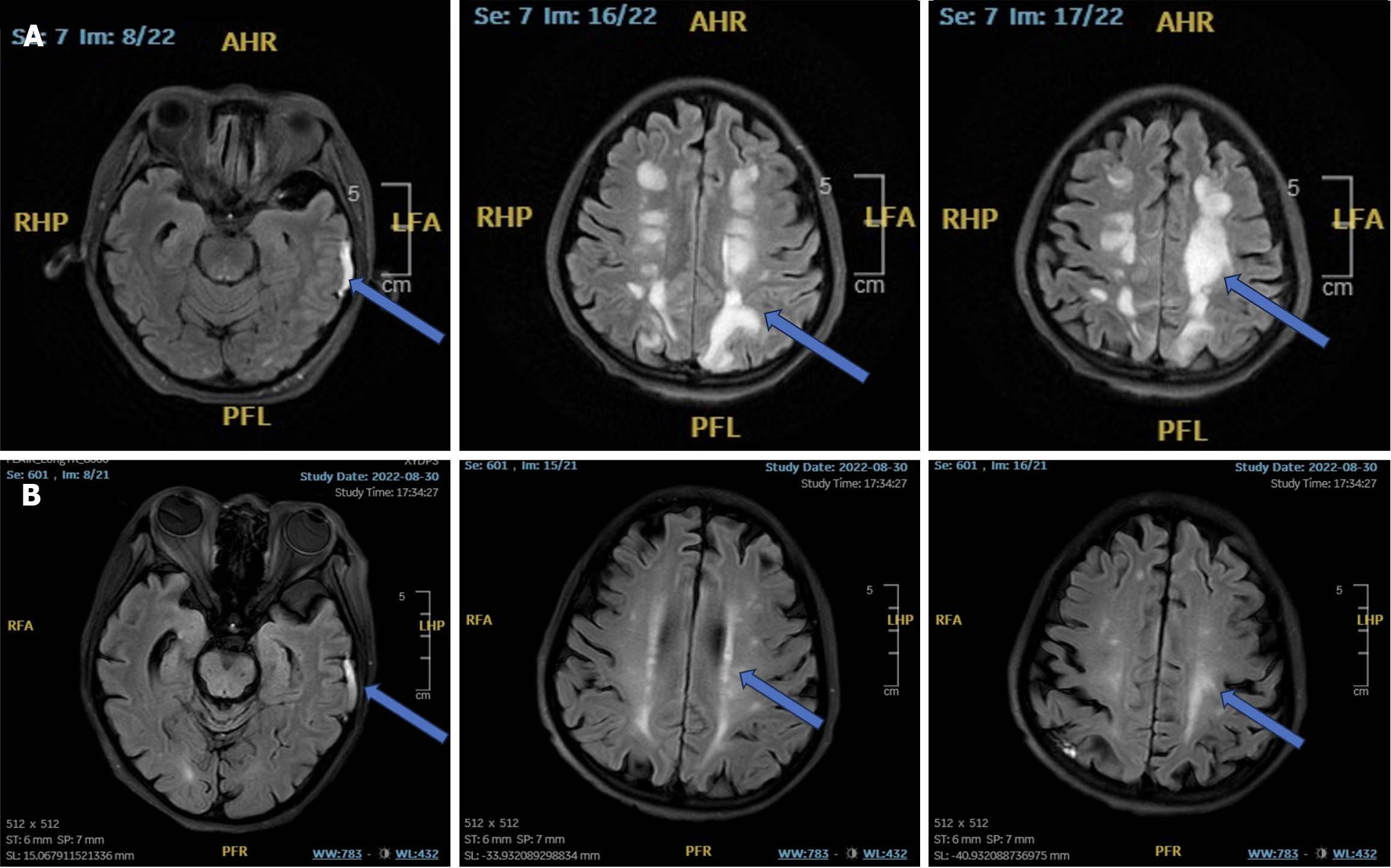

However, on July 22nd, 2022 (POD4), the patient experienced transient delirium and hypoxemia, which improved with oral Zyprexa and supportive high-flow oxygen therapy. On August 13th, 2022 (POD24), the patient presented with acute neurological symptoms, including headache, restlessness, transient loss of consciousness, and limb convulsions. Neurological examination showed unresponsiveness to stimuli and an inability to cooperate with physical assessments; however, the bilateral pupils were equal in size with intact direct and consensual light reflexes. Symmetrical bilateral frontal lines and nasolabial folds were present, along with involuntary movements in both limbs. Additionally, both Pap and Kirsch signs were negative. The initial cerebral MRI on August 13th, 2022 (POD24), revealed a subdural hemorrhage in the left temporal lobe and extensive white matter demyelination (Figure 2A). The differential diagnoses included secondary epilepsy, immune-mediated white matter lesions, and subdural hemorrhage. Methylprednisolone was initiated following a neurological consultation, and levetiracetam and topiramate were administered while tacrolimus was replaced with rapamycin. Strict blood pressure control was maintained throughout the patient’s stay in the intensive care unit, resulting in relatively stable vital signs. A follow-up cerebral MRI on August 30th, 2022 (POD43), revealed multiple demyelinating lesions in the brain along with a persistent subdural hemorrhage in the left temporal region (Figure 2B).

However, the diagnosis of osmotic demyelinating disease was under debated due to the absence of electrolyte disturbances was observed throughout the course of the illness. After replacing tacrolimus with rapamycin and administering a cumulative dose of 1580 mg of methylprednisolone, the neurological disorder gradually resolved.

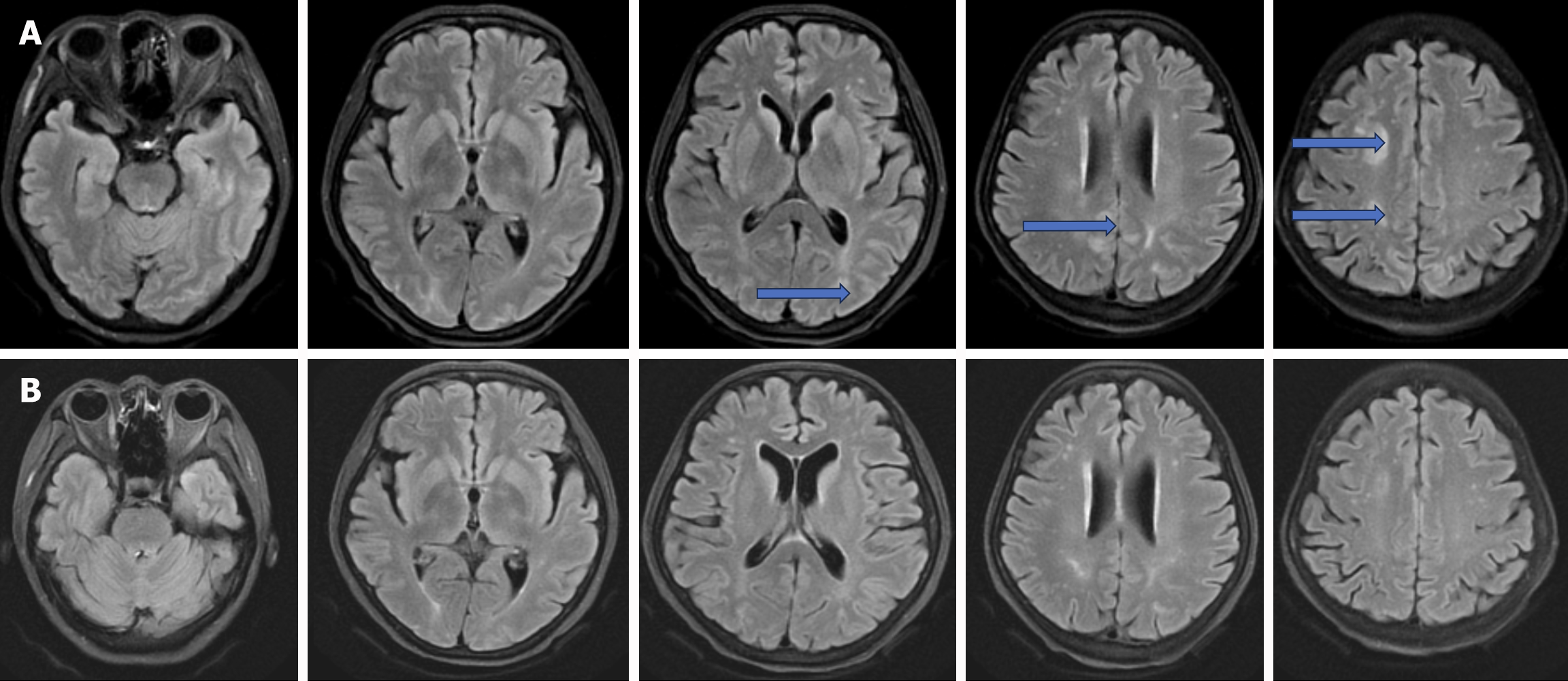

Case 3: The orthotopic liver transplantation was successfully performed at Zhongshan Hospital, affiliated with Fudan University, on May 23rd, 2023. She was placed on an immunosuppressive regimen comprising tacrolimus, mycophenolic acid, and methylprednisolone, resulting in peak tacrolimus trough levels reaching up to 12.1 ng/mL. The initial recovery period was uneventful until the early morning of June 3rd, when she experienced a sudden-onset headache associated with elevated blood pressure (160/100 mmHg), leading to a loss of consciousness lasting approximately five minutes, accompanied by frequent limb convulsions. These symptoms necessitated tracheal intubation and sedation with midazolam, along with antiepileptic therapy using levetiracetam. Following prompt intervention, the patient regained consciousness and remained seizure-free by June 5th. Her initial cerebral MRI suggested potential PRES (Figure 3A). Consequently, tacrolimus was replaced with rapamycin, and the methylprednisolone dose was increased to 80 mg twice daily. Follow-up imaging revealed the resolution of brain lesions (Figure 3B). The absence of subsequent symptoms led to her discharge on June 17th, 2023 (POD22).

Case 1: The patient reported no personal or family history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiopulmonary disease, specific medication use, or genetic conditions within her family lineage.

Case 2: She had no history of hypertension, diabetes, cardiopulmonary diseases, specific medication use, or genetic disorders in her family.

Case 3: The patient has no history of any other illnesses.

All of patient has no reported comorbidities, and there is no family history of genetic disorders.

Case 1: On June 15th, 2016 (POD9), the patient experienced a sudden onset of neurological symptoms, including seizures, staring spells, aphasia, and hemiplegia affecting the left limb, culminating in a loss of consciousness. Cerebral hemorrhage was ruled out based on cranial CT imaging, while initial cranial MRI revealed ischemic foci localized within the bilateral frontal lobes without significant involvement of the white matter. Subsequent laboratory investigations, including serological assays and electroencephalographic studies, yielded unremarkable results, prompting the initiation of antiepileptic therapy with levetiracetam, clonazepam, and alprostadil, along with adjunctive neuroprotective agents. Despite these interventions, no significant improvement was observed.

Case 2: On August 13th, 2022 (POD24), the patient presented with acute neurological dysfunction characterized by headache and restlessness, followed by transient disturbances of consciousness and limb convulsions. Neurological examination revealed unresponsiveness to stimuli and inability to cooperate with physical assessments; however, bilateral pupils were equal in size with intact direct and consensual light reflexes. Symmetrical bilateral frontal lines and nasolabial folds were observed, along with involuntary movements in both limbs. Both the Pap sign and Kirsch sign were negative. The initial cerebral MRI on August 13th, 2022 (POD24) demonstrated a subdural hemorrhage in the left temporal lobe as well as extensive white matter demyelination.

Case 3: In the early morning of June 3rd, 2023, the patient experienced a sudden-onset headache accompanied by elevated blood pressure (160/100 mmHg), leading to a loss of consciousness lasting approximately five minutes, along with frequent limb convulsions. These symptoms required tracheal intubation, followed by sedation with midazolam and antiepileptic therapy with levetiracetam. After these prompt interventions, the patient regained consciousness and remained seizure-free by June 5th, 2023.

After liver transplantation, the hematological parameters, hepatic and renal function, electrolyte levels, infection markers, and tacrolimus trough concentration in these three patients gradually normalized in the early stage.

Case 1: Firstly, cerebral hemorrhage was ruled out in this patient based on cranial CT findings, while initial cranial MRI revealed ischemic foci localized within the bilateral frontal lobes, with no significant involvement of the white matter regions (Figure 1A). Subsequent laboratory investigations, including serological assays and electroencephalographic studies, yielded unremarkable results, prompting the initiation of antiepileptic therapy with levetiracetam, clonazepam, and alprostadil, along with adjunctive neuroprotective agents. Despite these interventions, no significant improvement was observed. Subsequent cranial MRIs conducted on POD22 revealed persistent linear hyperintense signals involving the left posterior parietal region on DWI, along with patchy hyperintensity within the periventricular white matter and pontine areas bilaterally, as discerned using FLAIR sequences (Figure 1B).

As a result, the possibility of CNI-associated PRES was considered, leading to a transition in the immunosuppressive regimen from tacrolimus to rapamycin, along with an additional course of intravenous methylprednisolone totaling 1680 milligrams, which yielded a favorable response in terms of clinical symptoms. Subsequent evaluation via a third cranial MRI performed on POD66 demonstrated persistent aberrant signaling confined to the periventricular regions, displaying hypointensity during T1-weighted imaging and slight hyperintensity during T2-weighted imaging phases (Figure 1C).

Ultimately, a definitive diagnosis of CNI-induced PRES was established based on the concordance between clinical presentation and radiologic evidence. Despite persistent abnormalities observed across successive cranial MRIs, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and was ultimately discharged with normal hepatic function, undergoing regular follow-up extending beyond three years. The white matter lesions gradually resolved and were no longer detectable by the follow-up in 2019 (Figure 1D and E).

Case 2: On August 13th, 2022 (POD24), the patient experienced acute neurological symptoms, including headache and restlessness, followed by brief episodes of impaired consciousness and limb convulsions. Neurological assessment revealed a lack of response to stimuli and an inability to cooperate with physical examinations. However, the pupils were equal in size with preserved direct and consensual light reflexes. The patient exhibited symmetrical bilateral frontal lines and nasolabial folds, along with involuntary limb movements. Both Pap and Kirsch signs were negative. An initial cerebral MRI conducted on August 13th, 2022, revealed a subdural hemorrhage in the left temporal lobe and extensive white matter demyelination (Figure 2A). The differential diagnosis included secondary epilepsy, immune-mediated white matter lesions, and subdural hemorrhage. Consequently, methylprednisolone therapy was initiated following neurological consultation. Levetiracetam and topiramate were prescribed, and tacrolimus was replaced with rapamycin. Blood pressure was meticulously controlled during the patient’s stay in the intensive care unit, resulting in relatively stable vital signs. A follow-up cerebral MRI on August 30th, 2022 (POD43), showed multiple demyelinating lesions in the brain, along with a persistent subdural hemorrhage in the left temporal region (Figure 2B).

Case 3: The initial cerebral MRI indicated the possibility of PRES (Figure 3A). Consequently, tacrolimus was replaced with rapamycin, while the methylprednisolone dosage was increased to 80 mg twice daily. Follow-up imaging showed a resolution of the brain lesions (Figure 3B).

Given the patient’s history of tacrolimus use following liver transplantation, and the absence of other neurological conditions such as demyelinating diseases and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), modifications to or cessation of CNI therapy were implemented. Additionally, stringent blood pressure control, corticosteroid treatment, and supportive care were provided for the three patients.

A definitive diagnosis of CNIs-induced PRES was established based on the concordance between the clinical presentation and radiologic findings.

The diagnosis of osmotic demyelinating disease was debated due to the absence of electrolyte disturbances during the illness. However, after replacing tacrolimus with rapamycin and administering a cumulative dose of 1580 mg of methylprednisolone, the neurological symptoms gradually resolved. Consequently, a diagnosis of CNIs-related PRES was confirmed.

The diagnosis of CNIs-induced PRES was confirmed based on cerebral MRI findings.

The immunosuppressive regimen was modified by switching from tacrolimus to rapamycin and was further augmented with an additional course of intravenous methylprednisolone, totaling 1680 mg.

Tacrolimus was replaced with rapamycin, and methylprednisolone was administered continuously, totaling 1580 mg.

Tacrolimus therapy was transitioned to rapamycin, while the dose of methylprednisolone was increased to 80 mg twice daily.

Notwithstanding enduring abnormalities evident across successive cranial MRI, the patient remained hemodynamically stable ultimately achieving discharge normative hepatic function undergoing regular follow-up extending beyond three years. The white matter lesions in the patients gradually resolved and were no longer detectable by the follow-up in 2019 (Figure 1D and E).

The patient was discharged from the intensive care unit on September 29th, 2022 (POD81). Consequently, confirmation of CNI-related PRES led to her discharge on October 13th, 2022 (POD95).

The patient’s subsequent symptom resolution led to her successful discharge on June 17th, 2023 (POD22).

In summary, three patients exhibited complete recovery of their neurological symptoms without any complications and were discharged from the hospital in a favorable clinical condition.

Despite an increasing number of case reports and reviews addressing postoperative neurological complications in solid organ transplant recipients, the precise pathogenesis remains unclear and is thought to be associated with factors such as infections, immunosuppressive drugs, and electrolyte imbalances[19-21] such as hypomagnesemia, uncontrolled or persistent hypertension, significant fluctuations in blood pressure, as well as pre-existing cerebral lesions[9] and even infections. Previous studies have indicated that the prevalence of tacrolimus-induced PRES ranges from 1% to 6%[16,22]. Neurological symptoms were observed in over 80% of liver transplant recipients within the first three months after the operation[9]. However, some patients experienced the onset of PRES more than a year after liver transplantation[16,23]. The prognosis of patients with PRES varied depending on their clinical condition, with the majority experiencing complete recovery without any long-term effects[4,8,13,22], However, unfortunately, a small number of patients still succumb to the illness[24].

According to published reports, CNIs, particularly tacrolimus, are often implicated as a common trigger for PRES in liver transplant recipients[17,21,22,25]. However, neurotoxicity associated with CNIs is frequently observed even when tacrolimus trough levels are within the normal range. This occurs because tacrolimus, being a lipid-soluble drug, can cross the blood-brain barrier and directly exert toxic effects on the lipid-rich regions of white matter[7,8,12]. Given these considerations, reducing the dosage of tacrolimus or switching to alternative immunosuppressants may be a potentially safer and more effective approach. It is worth noting, however, that cyclosporin, another immunosuppressant, also has the potential to cause neuraxial edema[26]. Although the pathophysiology of PRES remains unclear, endothelial damage is believed to be one of the key mechanisms in the development of CNI-related PRES[8]. It has been suggested that CNIs may induce reversible vasogenic edema, leading to the disruption of cerebral blood vessel autoregulation, particularly affecting the posterior cerebral circulation. Vascular integrity is maintained by inter-endothelial adhesion molecules, while circulating toxins may trigger vascular leakage and subsequent edema[26,27]. In immune disorders and other systemic conditions, dysfunction in cerebrovascular regulation can result in hyperperfusion in the posterior cerebral circulation. This phenomenon explains the tendency for involvement of the frontal and occipital lobes in PRES, as observed in MRI findings that predominantly show changes in these regions. While magnetic resonance angiography of the brain typically appears normal in PRES cases, it can sometimes reveal focal vasoconstriction or vasodilation patterns suggestive of central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis. Additionally, magnetic resonance venography, which is usually unremarkable in PRES cases, can be helpful in ruling out sagittal sinus thrombosis[28,29].

Reports on the clinical manifestations of PRES include a range of atypical neurological symptoms[8]. Therefore, the onset of new headaches and transient fluctuations in blood pressure in liver transplant recipients should not be overlooked, as these may be early symptoms of PRES. The use of CNIs and timely cerebral imaging are crucial for early diagnosis. With prompt treatment, including transitioning to rapamycin and corticosteroid therapy, patients with PRES can experience rapid recovery, often accompanied by significant improvements in cerebral structural changes as seen on MRI scans[2,8,29]. Therefore, special attention should be given to newly occurring headaches, limb convulsions, transient loss of consciousness, and new persistent hypertension in post-transplantation patients. In addition to routine cerebral imaging scans, lumbar puncture may be performed in immunocompromised individuals to assess for encephalitis. Furthermore, brain biopsy has been recommended as a diagnostic tool for identifying the underlying cause in patients unresponsive to initial treatments.

Currently, the primary treatments for PRES focus on providing supportive care, including maintaining stable vital signs, closely managing blood pressure, replenishing electrolytes, adjusting the tacrolimus dosage or switching immunosuppressive medications, and administering antiepileptic drugs as needed[11,30]. Early diagnosis can enable most patients to benefit from these treatments. However, the routine use of corticosteroid therapy for treating PRES-associated vasogenic edema remains controversial due to the lack of evidence supporting its efficacy[8], some studies support that corticosteroid therapy often preceded the onset of PRES and was not significantly associated with the extent of vasogenic edema, suggesting it did not reduce the edema. However, according to our cases, the cautious administration of corticosteroid therapy, when not contraindicated, effectively ameliorated clinical symptoms and potentially had a positive impact on cerebral lesions.

The duration of cerebral lesions varied among PRES patients. In the first female patient, cerebral lesions persisted for approximately three years before gradually resolving in the affected white matter areas. In contrast, the cerebral lesions in the third patient resolved rapidly within 10 days after symptom onset. Furthermore, it was challenging to determine the presence of preexisting brain lesions in certain recipients prior to surgery due to the potential oversight of atypical clinical symptoms. Transplant candidates over 60 years old may already have localized white matter lesions due to cerebrovascular diseases. Although the prognosis for all three patients was relatively favorable, each had distinct clinical durations. Therefore, routine cerebral imaging scans are strongly recommended for organ transplant candidates, particularly those over 60 years old, and especially if they exhibit sharp fluctuations in perioperative blood pressure, electrolyte disturbances, hypoalbuminemia, or underlying infections or autoimmune diseases.

Finally, as reported in the literature, most patients with PRES have a favorable prognosis. However, if treatment is unsuccessful, it is important to promptly consider other neurological conditions, such as CNS infections, primary epilepsy, and PML[30-33]. PML which resulting from the reactivation of John Cunningham (JC) virus infection, typically occurs in immunocompromised individuals. Although PML is rare in liver transplant recipients, it is associated with a high mortality rate. The diagnosis of PML primarily relies on clinical manifestations, cerebral imaging, and polymerase chain reaction techniques to detect JC virus replication in cerebrospinal fluid.

In conclusion, while the neurotoxicity of CNIs is a significant factor, other variables also require careful evaluation in all organ transplant candidates. These include assessing comorbidities, prior medication history, preoperative cerebral imaging, and pre-existing viral infections. Additionally, independent risk factors for postoperative neurological complications include alcoholic liver disease, metabolic disorders, preoperative mechanical ventilation, model for end-stage liver disease scores exceeding 15, advanced age, elevated preoperative blood bilirubin levels, decreased platelet counts, severe lung infections, and renal insufficiency. Careful consideration of these factors is essential for optimizing patient outcomes post-transplantation[14,18,22,34,35]. Therefore, it is imperative to have a comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis, conduct a thorough assessment of risk factors, and implement effective preventive measures. Prompt diagnosis and timely treatment are also critical. Moreover, further investigation into specific therapies for CNI-related PRES is warranted in order to improve patient outcomes.

We would like to sincerely thank the medical and nursing staff at Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, for their exceptional care of the patients involved in this report. We also appreciate the support from our colleagues in the intensive care unit. Finally, we extend our gratitude to the patients and their families for their trust and cooperation.

| 1. | Vizzini G, Asaro M, Miraglia R, Gruttadauria S, Filì D, D'Antoni A, Petridis I, Marrone G, Pagano D, Gridelli B. Changing picture of central nervous system complications in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:1279-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kumar SS, Mashour GA, Picton P. Neurologic Considerations and Complications Related to Liver Transplantation. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:1008-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen S, Hu J, Xu L, Brandon D, Yu J, Zhang J. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome After Transplantation: a Review. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:6897-6909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yashi K, Virk J, Parikh T. Nivolumab-Induced PRES (Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome). Cureus. 2023;15:e40533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rovira A, Mínguez B, Aymerich FX, Jacas C, Huerga E, Córdoba J, Alonso J. Decreased white matter lesion volume and improved cognitive function after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2007;46:1485-1490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gewirtz AN, Gao V, Parauda SC, Robbins MS. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2021;25:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Siebert E, Bohner G, Liebig T, Endres M, Liman TG. Factors associated with fatal outcome in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a retrospective analysis of the Berlin PRES study. J Neurol. 2017;264:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Song T, Rao Z, Tan Q, Qiu Y, Liu J, Huang Z, Wang X, Lin T. Calcineurin Inhibitors Associated Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in Solid Organ Transplantation: Report of 2 Cases and Literature Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ramkissoon R, Yung-Lun Chin J, Jophlin L. Acute Neurological Symptoms After a Liver Transplant. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:2264-2266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Usta S, Karabulut K. A Late Complication Occurring Due to Tacrolimus After Liver Transplant: Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. Exp Clin Transplant. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Frühauf NR, Koeppen Dagger S, Saner FH, Egelhof Dagger T, Stavrou G, Nadalin S, Broelsch CE. Late onset of tacrolimus-related posterior leukoencephalopathy after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:983-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tseng WC, Lai HC, Yeh CC, Fan HL, Wu ZF. Overdose of Tacrolimus as the Trigger Causing Progression of Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome and Subsequent Hepatic Infarction After Liver Transplant: A Case Report. Exp Clin Transplant. 2020;18:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dashti-Khavidaki S, Moghadamnia M, Jafarian A, Chavoshi-Khamneh A, Moradi A, Ahmadinejad Z, Ghiasvand F, Tasa D, Nasiri-Toosi M, Taher M. Thrombotic Microangiopathy, Antibody-Mediated Rejection, and Posterior Reversible Leukoencephalopathy Syndrome in a Liver Transplant Recipient: Interplay Between COVID-19 and Its Treatment Modalities. Exp Clin Transplant. 2021;19:990-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hinduja A. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome: Clinical Features and Outcome. Front Neurol. 2020;11:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schuuring J, Wesseling P, Verrips A. Severe tacrolimus leukoencephalopathy after liver transplantation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:2085-2088. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, Pessin MS, Lamy C, Mas JL, Caplan LR. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2250] [Cited by in RCA: 2147] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Almoussa M, Goertzen A, Brauckmann S, Fauser B, Zimmermann CW. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome due to Hypomagnesemia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:1980638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chtioui H, Zimmermann A, Dufour JF. Unusual evolution of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) one year after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:588-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Santos MM, Tannuri AC, Gibelli NE, Ayoub AA, Maksoud-Filho JG, Andrade WC, Velhote MC, Silva MM, Pinho ML, Miyatani HT, Susuki L, Tannuri U. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome after liver transplantation in children: a rare complication related to calcineurin inhibitor effects. Pediatr Transplant. 2011;15:157-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marchiori PE, Mies S, Scaff M. Cyclosporine A-induced ocular opsoclonus and reversible leukoencephalopathy after orthotopic liver transplantation: brief report. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:195-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ball AM, Rayi A, Gustafson M. A Rare Association of Hypomagnesemia and Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES). Cureus. 2023;15:e41572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Geocadin RG. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:2171-2178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Heidenhain C, Puhl G, Neuhaus P. Late fulminant posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome after liver transplant. Exp Clin Transplant. 2009;7:180-183. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Hobson EV, Craven I, Blank SC. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: a truly treatable neurologic illness. Perit Dial Int. 2012;32:590-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bartynski WS, Boardman JF. Catheter angiography, MR angiography, and MR perfusion in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:447-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sezer T, Balcı Sezer O, Özçay F, Akdur A, Torgay A, Haberal M. Efficacy of Levetiracetam for Epilepsy in Pediatric Liver Transplant Recipients With Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome. Exp Clin Transplant. 2020;18:96-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Baldini M, Bartolini E, Gori S, Bonanni E, Cosottini M, Iudice A, Murri L. Epilepsy after neuroimaging normalization in a woman with tacrolimus-related posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17:558-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ahmadinejad Z, Talebi F, Yazdi NA, Ghiasvand F. A 41-year-old female with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after liver transplant. J Neurovirol. 2019;25:605-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cicora F, Roberti J. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy in a Kidney Transplant Recipient. Exp Clin Transplant. 2019;17:108-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ozdemir F, Ince V, Baskiran A, Ozdemir Z, Bayindir Y, Otlu B, Yilmaz S. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy after Three Consecutive Liver Transplantations. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2015;6:126-130. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Beck ES, Cortese I. Checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of JC virus-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Curr Opin Virol. 2020;40:19-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dumortier J, Guillaud O, Bosch A, Coppéré B, Petiot P, Roggerone S, Vukusic S, Boillot O. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after liver transplantation can have favorable or unfavorable outcome. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18:606-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Verhelst X, Vanhooren G, Vanopdenbosch L, Casselman J, Laleman W, Pirenne J, Nevens F, Orlent H. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in liver transplant recipients: a case report and review of the literature. Transpl Int. 2011;24:e30-e34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jeelani H, Sharma A, Halawa AM. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in Organ Transplantation. Exp Clin Transplant. 2022;20:642-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Anderson RC, Patel V, Sheikh-Bahaei N, Liu CSJ, Rajamohan AG, Shiroishi MS, Kim PE, Go JL, Lerner A, Acharya J. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES): Pathophysiology and Neuro-Imaging. Front Neurol. 2020;11:463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |