Published online Feb 27, 2024. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v16.i2.279

Peer-review started: November 16, 2023

First decision: December 25, 2023

Revised: December 29, 2023

Accepted: January 25, 2024

Article in press: January 25, 2024

Published online: February 27, 2024

Processing time: 102 Days and 21.6 Hours

Hepatic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis coinfections, particularly with concurrent abscesses and sinus tract formation, are extremely rare. This article presents a case of a patient diagnosed with this unique presentation, discussing the typical imaging manifestations of both echinococcosis types and detailing the diagnosis and surgical treatment experience thereof.

A 39-year-old Tibetan woman presented with concurrent hepatic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis, accompanied by abdominal wall abscesses and sinus tract formation. Initial conventional imaging examinations suggested only hepatic cystic echinococcosis, but intraoperative and postoperative pathological exami

Lesions involving the abdominal wall and sinus tract formation, may require radical resection. Long-term prognosis includes albendazole and follow-up examinations.

Core Tip: Echinococcosis, also known as hydatid disease, is a zoonotic parasitic disease caused by echinococcus infection, mostly parasitic in the liver. There are two common pathogenic types of hepatic echinococcosis, Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis. Infection with a single species of echinococcus was common, while co-infection with two species of echinococcus was rare, accounting for only 0.92% of the patients with hepatic echinococcosis. This article introduces the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with co-infection of two types of hepatic echinococcosis, abdominal wall abscess and sinus formation.

- Citation: Wang MM, An XQ, Chai JP, Yang JY, A JD, A XR. Coinfection with hepatic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis with abdominal wall abscess and sinus tract formation: A case report. World J Hepatol 2024; 16(2): 279-285

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v16/i2/279.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v16.i2.279

Echinococcosis is prevalent in pastoral areas like northwest and southwest China, with an average prevalence of approximately 1.08% in western China[1]. Two types of hepatic echinococcosis exist: Cystic echinococcosis (CE) caused by Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus), and alveolar echinococcosis (AE) caused by Echinococcus multilocularis (E. multilocularis). Clinical diagnosis relies primarily on imaging and immunological tests. Imaging typically involves abdominal ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT), while immunological detection employs enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)[2-4]. Definitive diagnosis requires pathological examination.

Currently, no established guidelines or general consensus exists for treating coinfections with both echinococcosis types, though radical resection is widely considered optimal[5-7]. Such coinfections are rare, representing only 0.92% of all hepatic echinococcosis cases, and can be difficult to diagnose and manage[4]. To date, only five such cases have been documented at Qinghai Provincial People's Hospital, China (Table 1). Notably, only one case involved concurrent abdominal wall invasion and sinus tract formation.

| No. | Sex | Age (yr) | Lesion (location) | Child-Pugh score | Surgery | Postoperative complication | Case characteristics |

| 1 | Female | 42 | S5 and S8 | A | Anatomic right hemihepatectomy | No | Surgical treatment of patients with preoperative misdiagnosis of echinococcosis and mixed infections of both types of echinococcosis should be based on ensuring the patient's surgical safety, and radical surgery should be performed to remove all lesions whenever possible |

| 2 | Female | 26 | S4, S5 and S8 | A | Removal of the internal capsule, with subtotal excision of the external capsule the in Echinococcus granulosus lesions | Bile leakage, ascites, and bilateral pleural effusions | The patient traveled to an out-of-state hospital for autologous liver transplantation. Staged surgical treatment may be considered in end-stage patients with insufficient residual liver volume or in advanced patients who cannot be completely resected at one time, and only palliative surgery or conservative treatment is required for patients who have lost the chance of radical surgical treatment |

| 3 | Female | 49 | S2, S3, S7 and S8 | A | Multiple segmental hepatectomy | No | Surgical treatment of patients with preoperative misdiagnosis of echinococcosis and mixed infections of both types of echinococcosis should be based on ensuring the patient's surgical safety, and radical surgery should be performed to remove all lesions whenever possible |

| 4 | Male | 56 | S4, S5, S6, S7 and S8 | A | Extended right hemicolectomy | No | Ultrasound-guided PTCD for jaundice reduction was performed on day 2 of admission, and jaundice was reduced until surgery on day 33 after admission |

| 5 | Female | 39 | S6 and S7 | A | Multiple hepatic segment resection with abdominal wall sinus resection | No | Misdiagnosed preoperatively as echinococcosis, intraoperative and postoperative pathology confirmed mixed infection of the two types of echinococcosis in the liver with abdominal wall abscesses and sinus tracts, and the surgery needed to be considered as radical resection of the lesions, sinus tracts, and abdominal wall abscesses, which in turn followed the principle of individualized treatment of echinococcosis |

This report details the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with a mixed hepatic echinococcosis infection, presenting with abdominal wall invasion and sinus tract formation, managed at the General Surgery Department of Qinghai Provincial People's Hospital.

A 39-year-old Tibetan woman presented to our hospital with intermittent upper abdominal pain and discomfort for over a month, worsening in the past week.

The patient had intermittent epigastric distension and pain in January without any obvious cause, not accompanied by nausea, vomiting, fever and other discomforts, and did not undergo formal diagnosis and treatment, and the above symptoms worsened a week ago, so the patient came to our outpatient clinic, and the outpatient clinic was admitted to the department of our department with "abdominal pain to be investigated", and the patient was in a clear state of mind since the onset of the disease, his mental state was clear, and the spirit was fine, and he had normal urination and defecation, and he did not see any significant reduction of his body weight in recent days. Since the onset of the disease, he has been in a clear state of mind, with a normal spirit, normal bowel movements and no significant weight loss.

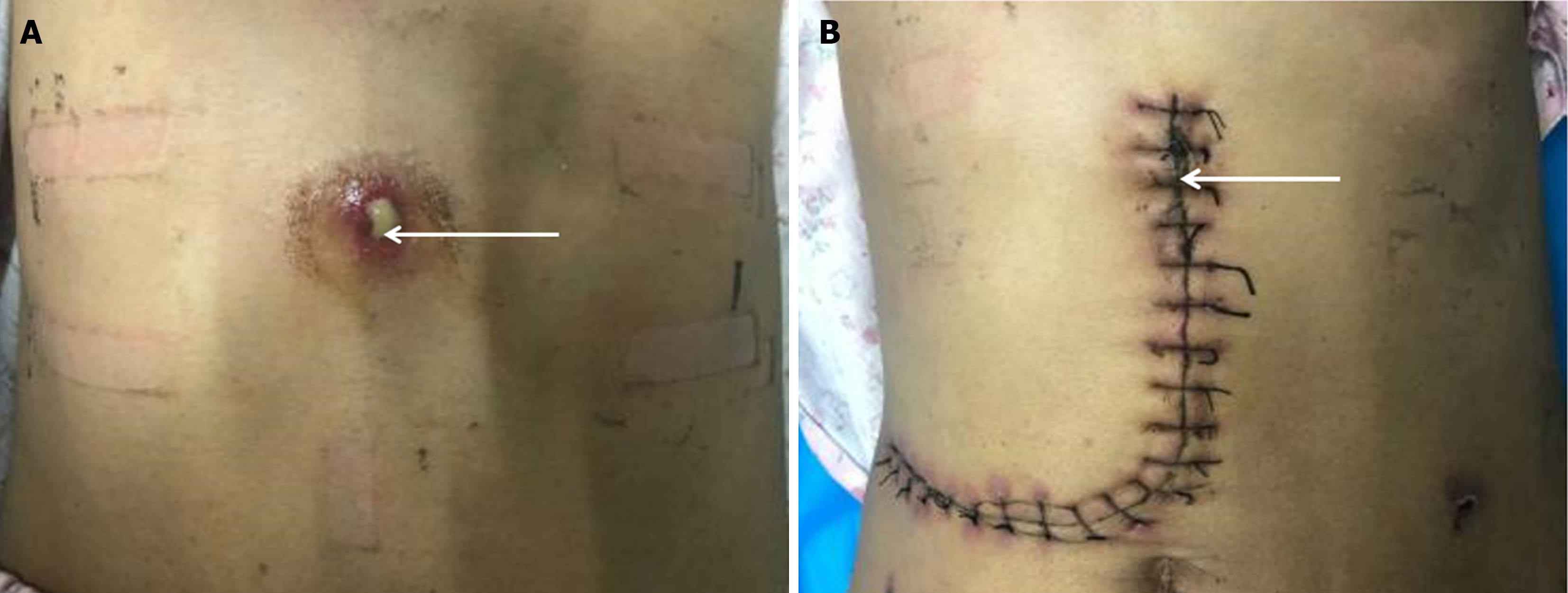

Physical examination revealed normal skin, sclerae, palpebral conjunctiva, heart, and lungs. However, an abdominal microbulge, skin rupture with pus outflow, and tenderness were found 5.0 cm above the umbilicus (Figure 1A). No abdominal varices, gastrointestinal peristalsis, or swelling were observed, but umbilical secretions and decreased abdominal breathing were present. Upper abdominal and periumbical tenderness, rebound pain, and muscle tension were noted, while the rest of the abdomen was unremarkable.

Initial laboratory tests showed: Red blood cells, 5.98 × 1012 cells/L; white blood cells, 5.54 × 1012 cells/L; hemoglobin, 167 g/L; and platelet count, 240 × 109 cells/L. Liver function tests revealed: Alanine aminotransferase, 9 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 13 U/L; total bilirubin, 7.2 mol/L; direct bilirubin, 1.4 mol/L; indirect bilirubin, 5.8 mol/L; albumin, 32.2 g/L; and cholinesterase, 6140 U/L. A hydatid ELISA test yielded a positive result.

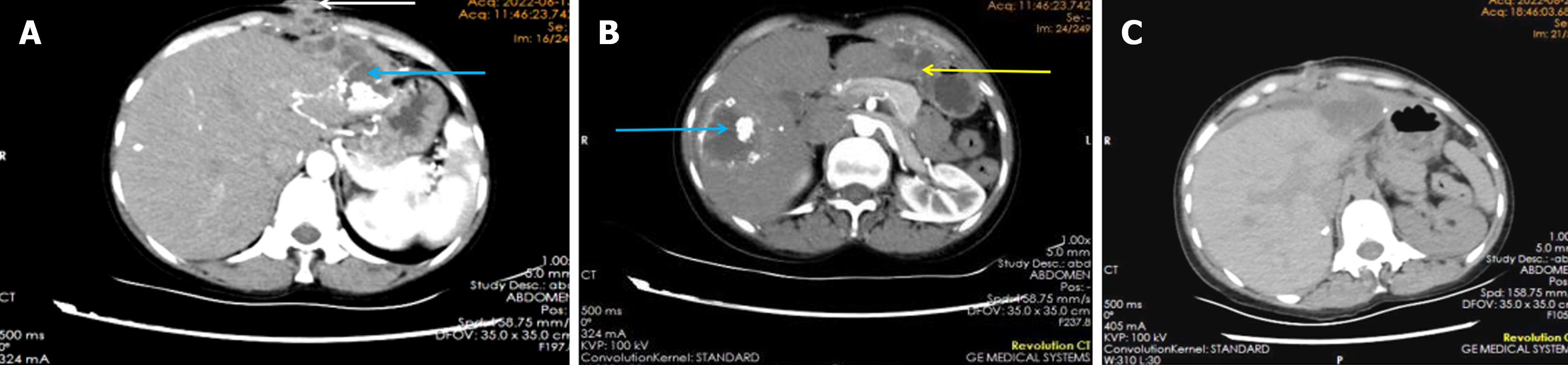

Abdominal color Doppler US revealed a 51 mm × 40 mm solid mass with a hyperechoic rim in the right hepatic lobe, suggestive of CE consolidation. Abdominal CT scan confirmed echinococcosis in the left lobe and anterior liver space, adhesion to the diaphragm, and a subxiphoid abscess with adjacent abdominal wall swelling. Scattered calcifications were identified within the right lobe CE (Figure 2A and B).

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of hepatic CE with abdominal wall abscesses was made. The preoperative evaluation showed normal cardiopulmonary function and Child–Pugh grade A (5 points).

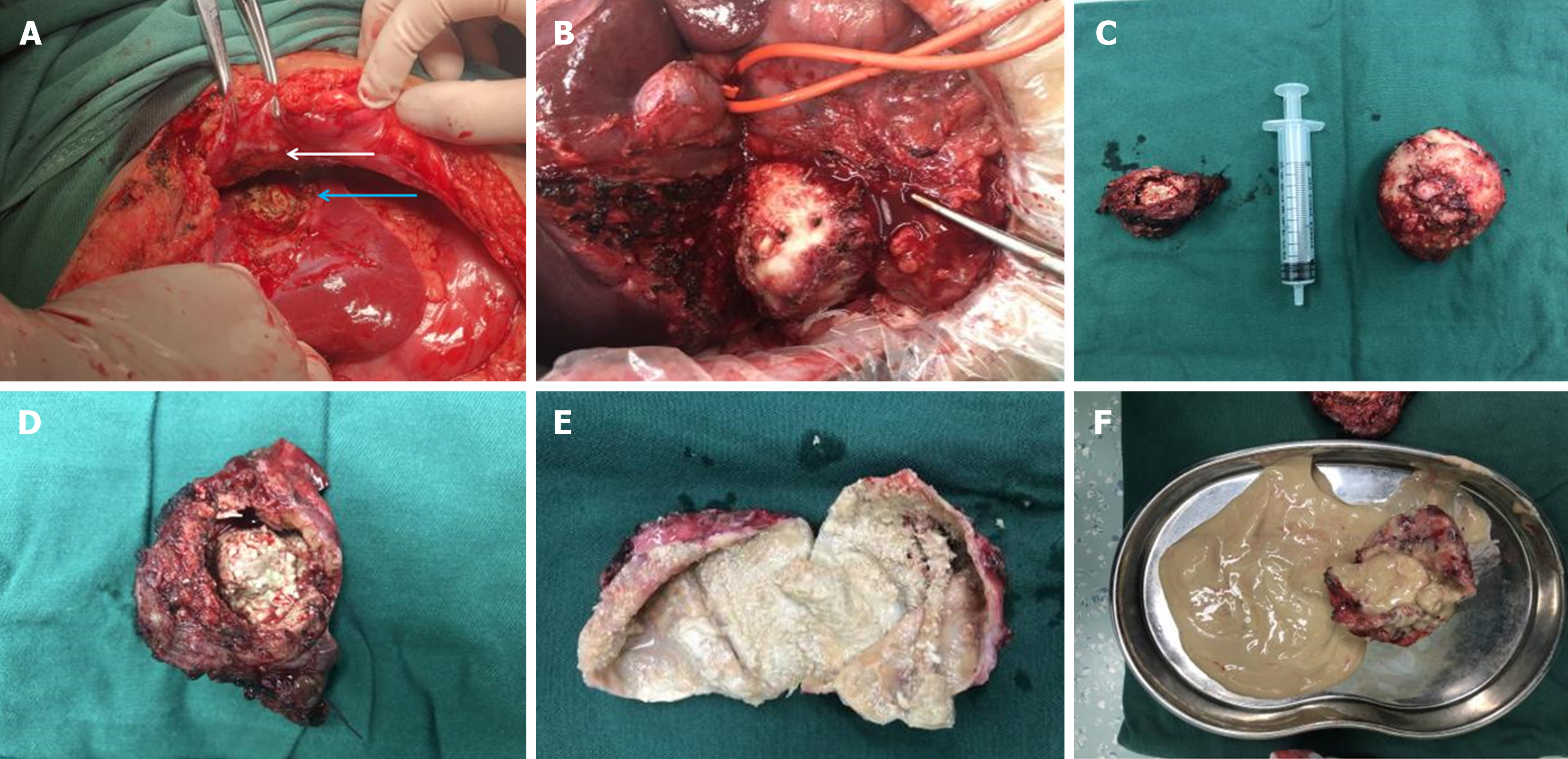

Intraoperatively (Figure 3), an oval cystic mass, measuring approximately 10.0 cm × 10.0 cm × 10.0 cm, was visualized in the right anterior hepatic lobe, exhibiting characteristics consistent with hepatic unilocular E. granulosus. Moreover, an irregular solid mass, measuring about 5.0 cm × 5.0 cm × 5.0 cm, in the left outer lobe was identified, presenting features compatible with hepatic E. multilocularis. Lastly, dense adhesions connected both masses to the anterior abdominal wall, characteristic of hepatic multilocular Echinococcus larvae.

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was revised to mixed-type encapsulated hepatic echinococcosis (cystic and alveolar), with abdominal wall abscess and sinus tract formation.

A combined multisegmental hepatectomy with abdominal wall sinus tract resection was performed.

Postoperatively, the patient was encouraged to wake up and eat early to promote organ function recovery[8]. A follow-up CT scan 7 days postoperatively revealed a blurred fat space in the surgical area, with effusion, gas accumulation, and slight swelling of the right lower abdominal wall, with minimal exudate and pneumatosis; and unchanged scattered calcifications in the liver (Figure 2C).

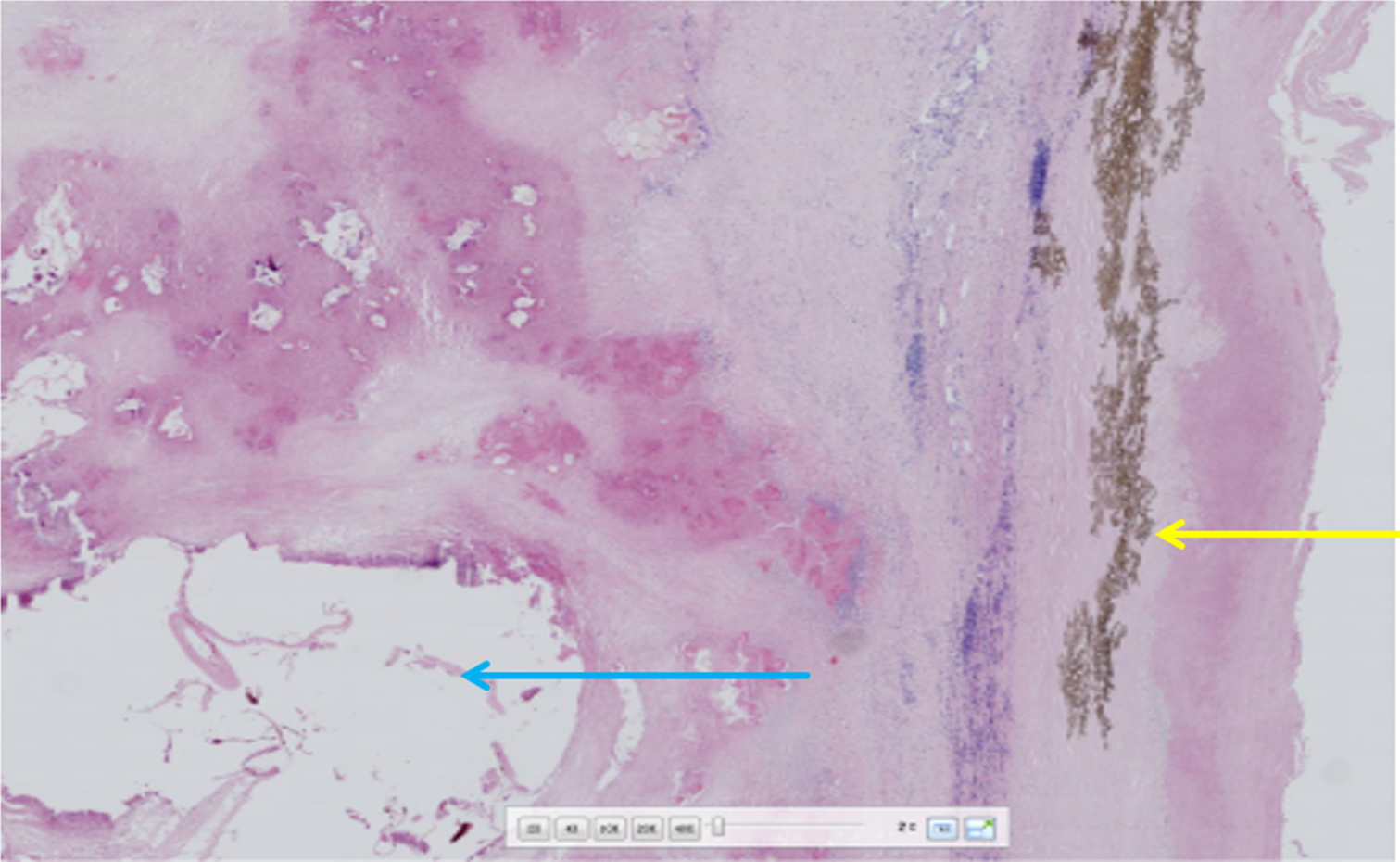

Pathological examination of the liver hydatid tissue and fibrous cyst wall tissue revealed fibrous hyperplasia with hyalinization, necrosis, calcification, inflammatory cell infiltration, and minimal lamellar structures, consistent with echinococcosis (Figure 4). Nine days after surgery, the abdominal incision had healed well (Figure 1B), and the patient was discharged.

Regular oral albendazole therapy was initiated, as per the 2019 diagnostic criteria and expert guidelines for hepatic echinococcosis.

While relying on the aforementioned criteria, this patient’s CT scan only revealed CE lesions and could not pinpoint the AE focus. Two factors might explain this. Initially, AE lesions often develop complete internal necrosis after infection, forming a thin and uniform abscess wall indistinguishable from CE on CT. Additionally, mixed CE and AE infections are uncommon and rarely appear clearly on scans. Even with CT, the optimal view for diagnosis is not always achieved, leading to potential bias in this report.

Surgical treatment for patients with combined CE and AE infections prioritizes surgical safety. Aim for radical surgery to remove all lesions comprehensively, while still employing individualized approaches for each patient. Postoperatively, all coinfected patients should adhere to the standard AE diagnosis and treatment regimen, involving ongoing benzimidazole therapy[8].

Echinococcosis primarily targets organs like the liver, lungs, and spleen, with abdominal wall invasion is highly unusual. This patient presented with a long-standing abdominal wall abscess and sinus tract, but had no other symptoms of discomfort. Despite no major liver vessel involvement, the complications were significant. For such cases, successful surgery hinges on radical resection of the abdominal wall abscess and sinus tract. Insufficient resection risks AE recurrence, while exceeding necessary bounds can compromise remaining liver volume and functionality, leaving a large abdominal wall defect. Therefore, surgeons must ensure a safe 1.0-cm resection margin while preserving enough normal abdominal tissue (transverse diameter < 3 cm) and adequate blood supply[9,10]. By adhering to these principles, supported by thorough preoperative evaluation, accurate surgical planning, and optimal postoperative care, our patient achieved complete recovery and was discharged without complications.

This report summarized our experience in diagnosing and treating this rare condition: A mixed infection of both Echinococcus species with abdominal wall invasion and sinus tract formation. While the general treatment principles remain consistent with those of a simple infection by either E. granulosus or E. multilocularis, the presence of these additional complications necessitates additional considerations. For patients with long-standing lesions and established sinus tracts, radical resection of the affected tissue, including the sinus tracts and any abdominal wall abscesses, should be considered during surgery. This aligns with the principle of individualized treatment of echinococcosis. However, the long-term prognosis for such patients require postoperative albendazole treatment and regular follow-up protocols.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oprea V, Romania S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Wang TP, Cao ZG. Current status of echinococcosis control in China and the existing challenges. Zhongguo Jishengchongxue Yu Jishengchongbing Zazhi. 2018;36:291-296. |

| 2. | Bayrak M, Altıntas Y. Current approaches in the surgical treatment of liver hydatid disease: single center experience. BMC Surg. 2019;19:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mihmanli M, Idiz UO, Kaya C, Demir U, Bostanci O, Omeroglu S, Bozkurt E. Current status of diagnosis and treatment of hepatic echinococcosis. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:1169-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Wen H, Xu MQ. Applied hydatid disease. Beijing: Science Press, 2007. |

| 5. | Committee of Hydatid Surgery; Society of Surgeons. Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of hepatic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis (2019 edition). Zhonghua Xiaohua Waike Zazhi. 2019;18:711-721. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Wen H, Vuitton L, Tuxun T, Li J, Vuitton DA, Zhang W, McManus DP. Echinococcosis: Advances in the 21st Century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 640] [Article Influence: 106.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kern P, Menezes da Silva A, Akhan O, Müllhaupt B, Vizcaychipi KA, Budke C, Vuitton DA. The Echinococcoses: Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Burden of Disease. Adv Parasitol. 2017;96:259-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang XQ, Hang XM, Tian QS, Zhao SY, A JD. Hepatic cystic and alveolar echinococcosis co-infections: a report of 3 cases. Zhongguo Xuexicheongbing Fangzhi Zazhi. 2020;32:213-216. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wu JG. Surgical strategies and significance of HIP2 expression for abdominal wall invasion of gastrointestinal cancer. Doctoral dissertations, Shanghai Jiaotong University School, 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Chinese Society of Hernia and Abdominal Wall Surgery, Chinese Society of Hernia and Abdominal Wall Surgery; Chinese Medical Doctor Association. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of abdominal wall incisional hernia (2018 edition). Zhonghua Waike Zazhi. 2018;56:499-502. [DOI] [Full Text] |