Published online Dec 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1315

Peer-review started: September 20, 2023

First decision: October 25, 2023

Revised: November 3, 2023

Accepted: November 21, 2023

Article in press: November 21, 2023

Published online: December 27, 2023

Processing time: 95 Days and 20 Hours

Patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection have increased serum omentin-1. Omentin-1 is an anti-inflammatory adipokine, and higher levels may be a direct effect of HCV infection. Successful elimination of HCV by direct acting antivirals almost normalized circulating levels of various molecules with a role in inflammation.

To evaluate the effect of HCV infection on serum omentin-1, serum omentin-1 levels of HCV patients were measured before therapy and at 12 wk after therapy end. Associations of serum omentin-1 with parameters of inflammation and liver function were explored at both time points. Serum omentin-1 levels of patients with and without liver cirrhosis, which was defined by ultrasound or the fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score, were compared.

Serum omentin-1 levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in 84 chronic HCV patients before therapy and at 12 wk after therapy end where sustained virological response 12 (SVR12) was achieved in all patients. Serum omentin-1 of 14 non-infected controls was measured in parallel.

In patients with chronic HCV, serum omentin-1 levels were not related to viral load or viral genotype. HCV patients with liver steatosis and HCV patients with diabetes had serum omentin-1 levels comparable to patients not suffering from these conditions. Serum omentin-1 levels at SVR12 were similar in comparison to pretreatment levels. In addition, serum levels did not differ between HCV-infected patients and non-infected controls. Serum omentin-1 levels did not correlate with leukocyte count or C-reactive protein. Positive correlations of serum omentin-1 with bilirubin and the model for end-stage liver disease score (MELD) were detected before therapy and at SVR12 in the whole cohort. Bilirubin and the MELD score also positively correlated with serum omentin-1 levels in the subgroup of patients with ultrasound diagnosed liver cirrhosis before therapy. At SVR12, serum omentin-1 levels of patients with liver cirrhosis negatively correlated with albumin. Before therapy start, patients with high FIB-4 scores had increased serum omentin-1 in comparison to patients with a low score. Serum omentin-1 levels of patients with liver cirrhosis defined by ultrasound were increased at baseline and at SVR12.

Present study showed that liver cirrhosis, but not HCV infection per se, is related to elevated serum omentin-1 levels.

Core Tip: Omentin-1 is an adipokine well described for its anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing functions. Aim of this study was to identify the effect of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and liver cirrhosis on serum omentin-1 levels. This study showed that circulating omentin-1 levels of HCV infected patients and non-infected healthy controls were similar. Accordingly, serum omentin-1 levels did not change upon effective elimination of the virus by direct acting antiviral therapy. Serum omentin-1 was not associated with diabetes or C-reactive protein in the HCV cohort. Patients with liver cirrhosis had increased serum omentin-1 levels before treatment and at sustained virological response 12 in comparison to HCV patients without liver cirrhosis. This analysis shows that increased serum omentin-1 levels of chronic HCV patients with liver cirrhosis persist after viral elimination. Serum omentin-1 has no role in the favourable metabolic outcomes of HCV eradication.

- Citation: Peschel G, Weigand K, Grimm J, Müller M, Buechler C. Serum omentin-1 is correlated with the severity of liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(12): 1315-1324

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i12/1315.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1315

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes systemic and hepatic inflammation, which drive the development and progression of liver fibrosis[1,2]. Highly effective elimination of HCV by direct acting antivirals (DAAs) rapidly improves inflammation and circulating levels of various cytokines and chemokines decline[3-5]. Interestingly, levels of pro- as well as anti-inflammatory cytokines were reduced shortly after start of DAA therapy[3-6]. Regression of liver fibrosis after HCV cure is possible, and complete reversal is expected to take several years[7]. Non-invasive tests for scoring of liver fibrosis are sonographic shear-wave elastography and transient elastography, and improvement of these measures at sustained virological response 12 (SVR12) or SVR24 is correlated with the resolution of liver inflammation[4,8]. The fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score is calculated from age, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) as well as platelet number, and was found accurate to assess advanced liver fibrosis in patients with HCV[9]. ALT and AST levels rapidly decline after start of DAA therapy, and lower FIB-4 scores at SVR12 are attributable to reduced hepatic inflammation[4,10].

Omentin-1 was first described as intelectin-1, a protein expressed in the intestine, which recognizes complex carbohydrates of bacterial cell walls. Later on, omentin-1 was shown to be highly expressed by stromal vascular cells of visceral adipose tissues. Omentin-1 protects from oxidative stress and exerts anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages, endothelial cells and adipocytes[11]. Omentin-1 serum levels are decreased in obesity and negatively correlate with fasting insulin levels[12]. There is convincing evidence that low serum omentin-1 levels in obesity contribute to impaired insulin signalling and insulin resistance[12-14].

Insulin resistance in chronic HCV infection is common, but the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. HCV-infected patients with elevated aminotransferase levels also had increased serum omentin-1. In this cohort, HCV patients with type 2 diabetes had lower serum omentin-1, which was negatively correlated with the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index and fasting insulin levels[15]. Serum omentin-1 concentrations of HCV patients with liver cirrhosis stratified by a HOMA-IR index below and above 2.5 were, however, similar[16]. Insulin resistance is associated with liver steatosis, which was not related to altered serum omentin-1 levels. Moreover, there was no correlation of serum omentin-1 levels with liver inflammation grades[16,17].

However, patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and patients with HCV-related liver cirrhosis had increased serum omentin-1 levels in comparison to healthy controls[17,18]. No significant differences in omentin-1 serum levels were found regarding the severity of liver cirrhosis assessed by the model of end stage liver disease (MELD) score or Child-Pugh score[18,19]. Accordingly, another study could not observe associations of serum omentin-1 levels with histologically scored fibrosis stages in patients with HCV[17]. In contrast, it was also reported that HCV patients with advanced liver fibrosis, which was histologically scored, had higher serum omentin-1 levels in comparison to those patients with a lower score[16].

Current studies suggest that serum omentin-1 is increased in chronic HCV, but whether this is caused by viral infection or related to liver disease severity has not been clarified to date. Aim of this study was to examine the effect of efficient virus elimination by DAA therapy on serum omentin-1 levels and to describe associations of serum omentin-1 levels with measures of liver disease severity.

This prospective study included patients with chronic HCV from September 1, 2014 to February 27, 2017, and was conducted at the Department of Internal Medicine I at the University Hospital Regensburg. Patients with an indication for therapy with DAAs (drug combinations used were sofosbuvir/daclatasvir, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, or elbasvir/grazoprevir) according to recent guidelines participated in the study[20]. The patients were older than 18 years, and had not been treated for HCV before. Patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis, hepatitis B virus or human immunodeficiency virus co-infection were excluded. The 14 controls were patients not infected with HCV, and without any severe diseases such as liver cirrhosis. This group included eight females and six males. Age was 63 (38-87) years and body mass index (BMI) was 26.9 (17.8-43.4) kg/m2, and both measures were similar to the patient cohort (P > 0.05 for all).

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the University Hospital of Regensburg (14-101-0049, date of approval May 22, 2014) and was performed according to the updated guidelines of good clinical practice and updated Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Laboratory measures were provided by the Institute of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, University Hospital Regensburg.

Cirrhosis diagnosis by ultrasound relied on nodular liver surface, small liver size, and coarse liver parenchyma[21]. The FIB-4 score is an accepted non-invasive fibrosis score[22]. Cut-off values for the FIB4-score were: fibrosis > 3.25, no fibrosis: < 1.3 for patients < 65 years, and < 2 for patients older than 65 years[23].

Serum aliquots were stored at -80 °C and thawed immediately before being used. Serum was used undiluted for omentin-1 measurement with the Human Intelectin-1/Omentin DuoSet enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems; Catalog #: DY4254-05; Wiesbaden-Nordenstadt, Germany).

Levels of the cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10 were quantified using Multiplex Luminex® Assays (Merck, KGaA, Germany) as described before[4].

Data are shown as boxplots, which represent the minimum value, the maximum value, the median, the first quartile and the third quartile. Small circles and asterisks above the boxes are outliers. Data in tables are given as median value, and the minimum value and the maximum value are listed in brackets. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used for comparison of two or more independent groups, respectively (SPSS Statistics 26.0 program). Students’ t-test (Ms Excel) was used for analysis of paired data and Spearman correlation for correlation analysis (SPSS Statistics 26.0 program). A value of P < 0.05 was regarded significant.

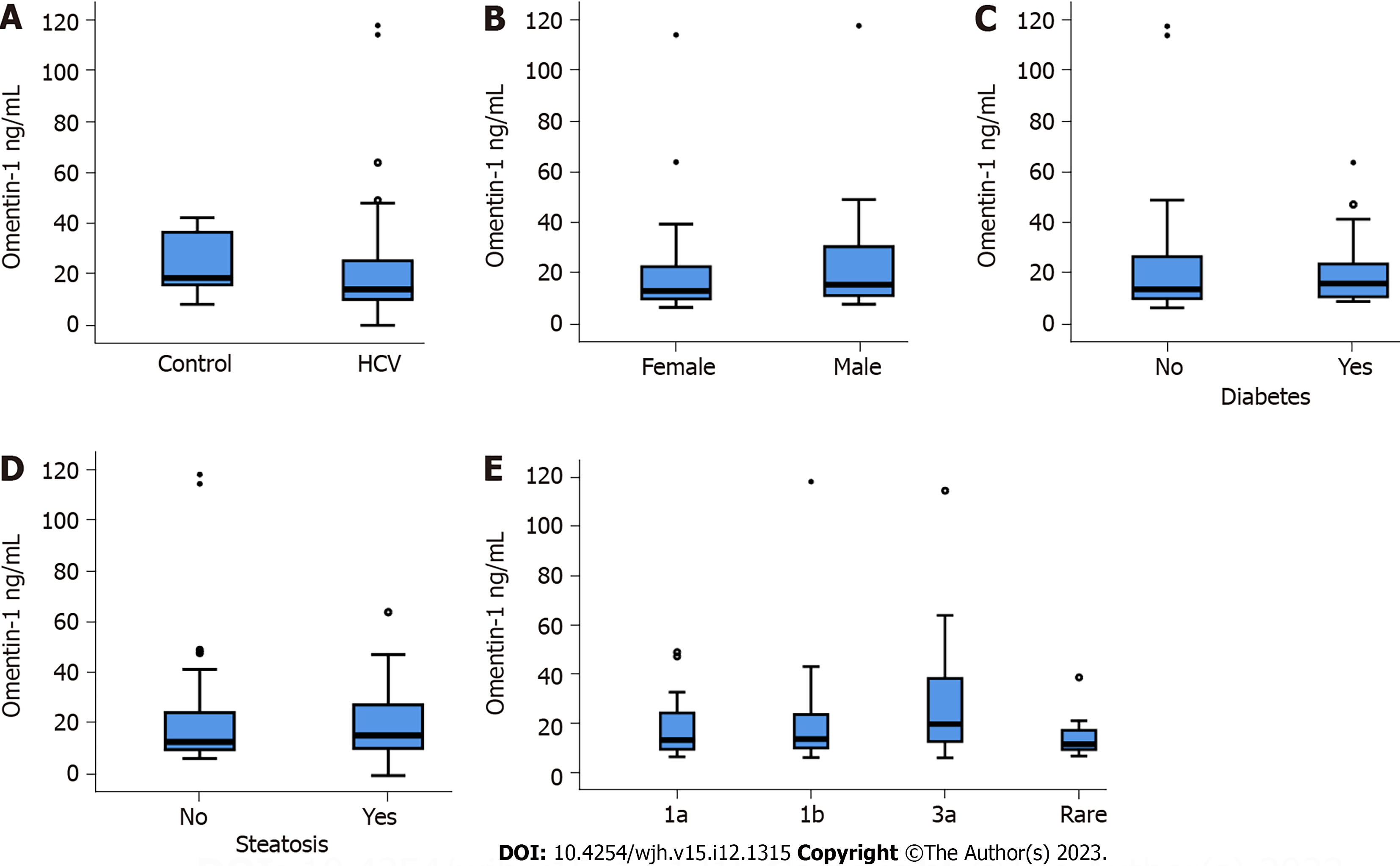

Eighty-four patients with chronic HCV infection (Table 1) and 14 non-infected controls were included in the study. Serum omentin-1 levels of controls and HCV patients were similar (Figure 1A). In the HCV cohort, serum omentin-1 levels of females and males were comparable (Figure 1B). Associations of serum omentin-1 with the BMI (r = -0.082, P = 0.486) or age (r = 0.092, P = 0.408) were not identified. The 15 diabetic HCV patients had similar omentin-1 serum levels in comparison to the non-diabetic HCV patients (Figure 1C). Ten of the patients with diabetes had liver cirrhosis, as was diagnosed by ultrasound imaging. In the cirrhosis group diabetic and non-diabetic patients had comparable serum omentin-1 levels (P = 1.00). Thirty-eight patients of the HCV cohort had liver steatosis but serum omentin-1 did not differ from patients without liver steatosis (Figure 1D).

| Parameter | Before therapy | Patients at SVR12 |

| Gender (F/M) | 37/47 | 36/42 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 26.5 (18.4-40.4) | 26.8 (18.4-40.4) |

| Age yr | 56 (24-82) | 57 (24-82) |

| MELD score | 7 (6-19) | 7 (6-19) |

| ALT U/L | 70 (22-247) | 26 (6-135)c |

| AST U/L | 64 (14-1230) | 23 (10-1390), n = 76c |

| Bilirubin mg/dL | 1.0 (1.0-4.3) | 1.0 (1.0-2.8) |

| Albumin g/L | 37.3 (19.0–45.5), n = 83 | 39.1 (26.1-47.7)c |

| INR | 1.1 (1.0-2.3) | 1.1 (1.0-2.8) |

| Creatinine mg/dL | 1.0 (1.0-1.3) | 1.0 (1.0-1.4) |

| GFR ml/min | 98 (47-161) | 94 (52–129) |

| Leukocyte number/L | 6.1 (2.2-12.3) | 6.2 (1.9-38.6), n = 77 |

| CRP mg/L | 2.9 (2.9-29.9) | 2.9 (2.9-20.4) |

| PCT ng/mL | 0.08 (0.01–11.02), n = 83 | 0.04 (0.01-0.15)c |

| Platelet number/nL | 157 (38-364) | 171 (38-312), n = 77 |

| HDL mg/dL | 52 (19-103), n = 78 | 51 (23-100), n = 71 |

| LDL mg/dL | 91 (31-204), n = 78 | 117 (38-243), n = 70c |

Serum omentin-1 was not related to viral load (r = -0.100, P = 0.364). HCV genotypes were 1a (22 patients), 1b (39 patients) and 3a (15 patients), and rare genotypes (8 patients) were assigned to one group. Serum omentin-1 levels did not vary between HCV genotypes (Figure 1E).

In the whole cohort, serum omentin-1 levels positively correlated with the MELD score (r = 0.428, P < 0.001), bilirubin (r = 0.435, P < 0.001), international normalized ratio (INR) (r = 0.380, P < 0.001) and procalcitonin (r = 0.365, P = 0.001), and negatively with platelet number (r = -0.303, P = 0.005), albumin (r = -0.297, P = 0.006) and low density lipoprotein (LDL) (r = -0.426, P < 0.001). Partial correlation of serum omentin-1 with LDL controlled for the MELD score was not significant (P = 0.075). Serum omentin-1 levels did not correlate with creatinine (r = 0.176, P = 0.107) or glomerular filtration rate (r =

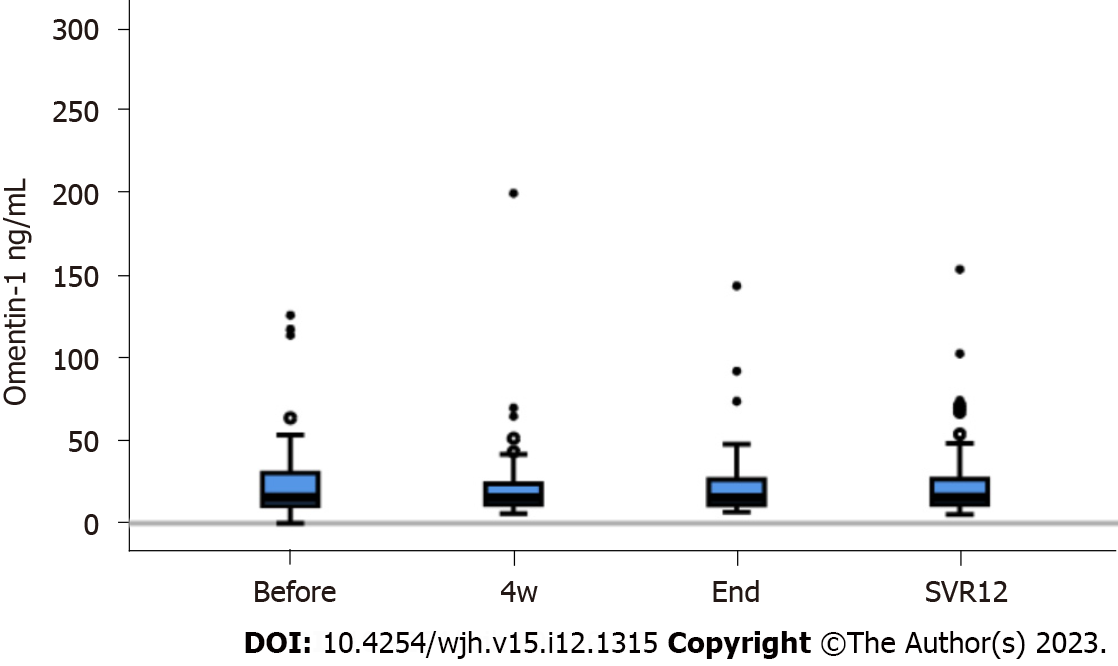

DAA therapy cleared HCV effectively and viral load was significantly reduced at four weeks after therapy start and at SVR12 (P < 0.001 in comparison to pre-treatment levels)[24]. At SVR12, ALT, AST, ferritin and procalcitonin were declined, and albumin and LDL were increased in contrast to levels before therapy (Table 1). Serum omentin-1 levels did not change during therapy (Figure 2).

Associations between serum omentin-1 and most of the clinical markers of liver disease severity persisted at SVR12. Serum omentin-1 levels correlated with the MELD score (r = 0.314, P = 0.005), bilirubin (r = 0.435, P < 0.001), albumin (r = -0.255, P = 0.025), INR (r = 0.293, P = 0.009) and LDL (r = -0.265, P = 0.027). Partial correlation of omentin-1 and LDL corrected for the MELD score was not significant (P = 0.625).

Serum omentin-1 did not correlate with creatinine (r = 0.047, P = 0.685) or glomerular filtration rate (r = -0.112, P = 0.334).

Serum omentin-1 did not correlate with leukocyte count (r = -0.205, P = 0.061), C-reactive protein (r = 0.117, P = 0.290), IL-6 (0.022, P = 0.113) or IL-10 (r = -0.138, P = 0.218) levels before DAA therapy. At SVR12 no significant associations between serum omentin-1 with leukocyte count (r = -0.093, P = 0.423), C-reactive protein (r = -0.098, P = 0.394), IL-6 (r = 0.067, P = 0.578) or IL-10 (r = 0.225, P = 0.058) were found.

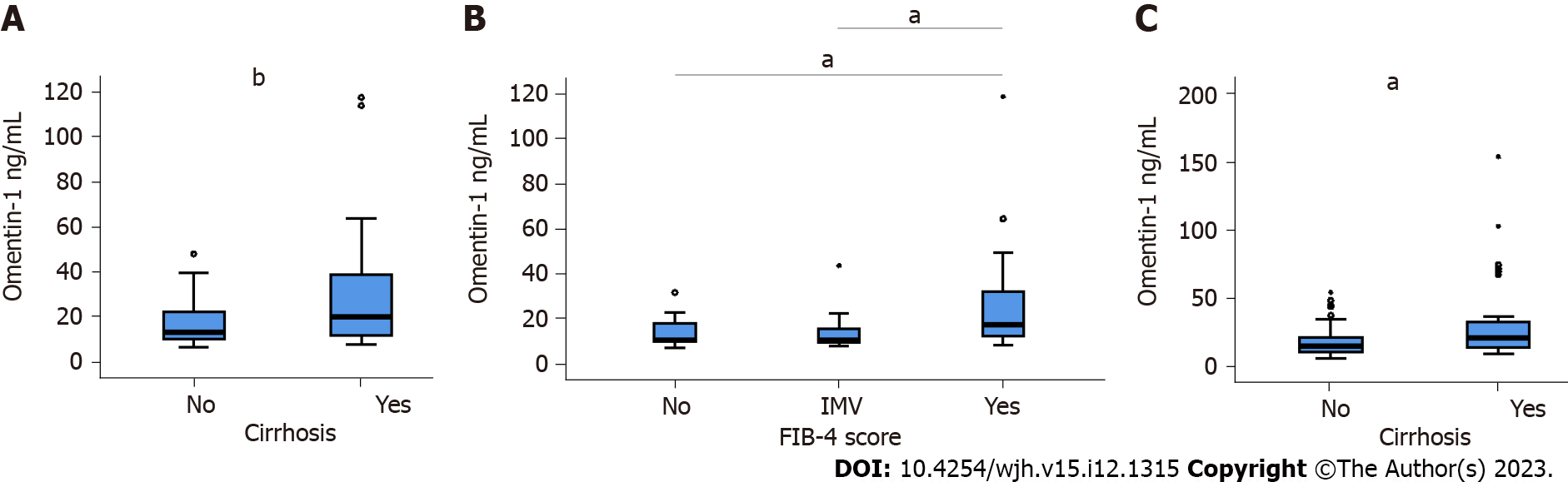

Before therapy, the 31 patients with liver cirrhosis diagnosed by ultrasound examination had higher omentin-1 (Figure 3A). The FIB-4 index for non-invasive scoring of liver fibrosis indicated higher omentin-1 serum levels of patients with advanced liver fibrosis in comparison to patients with low and intermediate scores (Figure 3B). Positive correlations with the MELD score (r = 0.375, P = 0.031) and bilirubin (r = 0.481, P < 0.005), and a negative correlation with LDL (r =

AT SVR12, in the subgroup of patients with ultrasound diagnosed liver cirrhosis, a negative correlation of albumin and serum omentin-1 was detected (r = -0.436, P = 0.018). Serum omentin-1 levels of patients with cirrhosis were higher in contrast to HCV patients without cirrhosis at SVR12 (Figure 3C).

Here, we have shown that serum omentin-1 is increased in HCV patients with advanced liver fibrosis. HCV infection per se did not affect serum omentin-1 levels, which were not related to viral titer or genotype, did not decline upon efficient elimination of HCV and were similar among HCV patients and non-infected controls.

In our previous study we have measured serum omentin-1 levels of patients with liver cirrhosis[18], and the 37 patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and the 3 patients with HCV related cirrhosis had similar levels (P = 0.693). Though the number of patients with HCV caused cirrhosis was small, this finding is in accordance with the assumption that HCV infection has no effect on serum omentin-1 levels.

Omentin-1 is best described for its role as an insulin-sensitizer[11,12]. Serum omentin-1 was, however, similar between diabetic and non-diabetic HCV patients in accordance with previous studies. It has been shown before that patients with liver cirrhosis and diabetes had similar omentin-1 levels in comparison to non-diabetic cirrhosis patients[19]. In addition, chronic HCV patients with a high HOMA-IR index had omentin-1 levels comparable to patients with a low index[16]. In apparently healthy cohorts, serum omentin-1 correlated negatively with the HOMA-IR index[14,25], and this association seems to be lost in chronic HCV.

HCV infection can promote diabetes and liver steatosis[26]. Metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is relatively common in the general population, and accordingly, is abundant in patients with HCV[27]. MAFLD is associated with insulin resistance, and reduced levels of circulating omentin-1[11,28]. In the HCV cohort, serum omentin-1 levels of patients with hepatic steatosis did not change. The diagnosis of MAFLD in patients with HCV infection is, however, challenging[27] and virus-induced fatty liver was not discriminated from metabolic liver steatosis in our study. Therefore, we can only conclude that liver steatosis either caused by HCV and/or by metabolic dysfunction is not related to changed serum omentin-1 levels.

HCV is classified into eight genotypes and more than 80 subtypes[29]. Most prevalent in Europe is HCV genotype 1 and the subtypes 1a and 1b[30], and 61 of our patients were infected by 1a or 1b. The second most prevalent genotype in our study cohort was 3a. HCV genotypes differ in their clinical features, and insulin resistance and liver steatosis are more common in genotype 1 and 3 infection[31]. Serum omentin-1 levels of patients infected with genotype 1a, 1b or 3a were, however, similar.

In accordance with previous data[16], serum omentin-1 levels were not associated with viral load. Highly efficient elimination of HCV by DAA treatment had no effect on the circulating levels of omentin-1. This indicates that hepatic and systemic inflammation caused by HCV infection[4] do not change serum omentin-1 levels. In line with this suggestion the current analysis showed that serum omentin-1 levels of HCV patients and controls were similar.

HCV patients with advanced liver fibrosis had increased serum omentin-1 levels when liver fibrosis was assessed by the non-invasive FIB-4 score or diagnosed by ultrasound. Higher concentrations of omentin-1 have been described in HCV patients with liver cirrhosis in comparison to healthy controls[17,18]. Current findings suggest that severe liver disease and not viral infection is the cause of increased serum omentin-1 levels.

Serum omentin-1 levels did, however not increase with higher Child-Pugh scores and did not correlate with the MELD score in patients with mostly alcoholic liver cirrhosis[18]. In our HCV patients with liver cirrhosis, serum omentin-1 levels did not correlate with the MELD score at SVR12. At this time, there was an association between serum omentin-1 and albumin, a biomarker for impaired hepatic function. Small cirrhosis cohorts and relatively weak associations between serum omentin-1 levels and laboratory measures of liver disease may prevent the observation of significant associations. Future research has to identify the causes for higher serum omentin-1 levels in patients with advanced liver fibrosis.

LDL of patients with liver cirrhosis is reduced[32-34], and negative correlation of serum omentin-1 levels with LDL is in this context. Negative associations of serum omentin-1 and LDL have been reported in healthy controls[35] and this finding is in line with the beneficial metabolic effects of this adipokine[11]. In HCV infection and at SVR12 the protective effects of omentin-1 against dyslipidemia could not be observed.

Increased serum omentin-1 levels of patients with advanced liver disease may originate from visceral adipose tissues with high omentin-1 expression[11]. It has been also suggested that impaired hepatic clearance of serum omentin-1 by the damaged liver contributes to higher serum levels[18]. Serum omentin-1 levels of patients with chronic HCV were not correlated with the hepatic mRNA expression of omentin-1[17], indicating that omentin-1 synthesis in the liver plays a minor role for systemic omentin-1 levels. Further study is needed to clarify the origin of higher serum omentin-1 in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Patients with end-stage renal disease had elevated serum omentin-1[36] indicating renal excretion of omentin-1. In the current analysis, which included patients with normal and slightly reduced glomerular filtration rates, associations between serum omentin-1 levels and markers for kidney function such as creatinine or glomerular filtration rates were not observed [37] This shows that minor renal dysfunction has no role for higher serum omentin-1 levels in HCV patients with liver cirrhosis.

Induction of omentin-1 levels of patients with liver cirrhosis is in agreement with studies on serum adiponectin levels, an anti-inflammatory adipokine functioning as an insulin sensitizer, whose circulating levels also decline in obesity[38,39]. Serum adiponectin levels of patients with HCV, hepatitis B virus and MAFLD related liver cirrhosis were increased[40]. In these patient cohorts, circulating levels of adiponectin were not associated with BMI or markers of insulin sensitivity[41]. These findings suggest that adiponectin does not exert its protective roles in liver cirrhosis as seems to be the case for omentin-1.

A limitation of this study is that Child-Pugh scores were not included. Early guidelines commenting on treatment in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis, who have Child-Pugh B or C, did not recommend the use of DAAs for these patients[42]. Our cohort was recruited shortly after these drugs were approved, and patients with decompensated cirrhosis were excluded. The Child-Pugh score of our cohort was not determined but from the clinical data of our patients we assume that most of them had Child-Pugh score A.

In summary, the current analysis showed that higher serum omentin-1 levels in chronic HCV infection is not a marker of metabolic health but rather indicates advanced liver fibrosis.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can cause severe liver damage. Chronic HCV infection can be cured with direct acting antiviral therapy, which also decreases insulin resistance. Omentin-1 is regarded a beneficial adipokine and improves insulin resistance. Serum omentin-1 levels are increased in HCV infection. The effect of viral cure on serum omentin-1 levels has not been analysed as far as we know. Moreover, data regarding associations of omentin-1 with liver injury are discordant.

From a pathophysiological standpoint, it can be important to evaluate associations of serum omentin-1 levels with HCV infection and liver disease severity.

The objective of this study was to assess the effect of HCV clearance on serum omentin-1 levels, and to evaluate associations of serum omentin-1 levels with clinical markers of inflammation, liver steatosis, diabetes and liver dysfunction.

This observational study included 84 patients with chronic HCV, and collected serum before therapy, at 4 wk after therapy start, at therapy end and at sustained viological response 12 (SVR12). Serum omentin-1 was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Serum omentin-1 levels of 14 controls were also determined.

The study found evidence of increased serum omentin-1 levels in patients with liver cirrhosis. HCV elimination did not change serum omentin-1 levels, suggesting that viral infection has no effect on serum omentin-1.

Effective elimination of HCV is associated with favourable metabolic outcomes. This study indicates that omentin-1 has no role herein. Serum omentin-1 of HCV patients with liver cirrhosis is increased at baseline and SVR12, and may have a role in liver cirrhosis pathogenesis.

Evaluation whether increased serum omentin-1 is just a marker of impaired liver function or contributes to liver damage.

The authors are very grateful to Elena Underberg for excellent technical assistance.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Virology

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang YC, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | de Torres M, Poynard T. Risk factors for liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol. 2003;2:5-11. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Li H, Huang MH, Jiang JD, Peng ZG. Hepatitis C: From inflammatory pathogenesis to anti-inflammatory/hepatoprotective therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:5297-5311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hengst J, Falk CS, Schlaphoff V, Deterding K, Manns MP, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H. Direct-Acting Antiviral-Induced Hepatitis C Virus Clearance Does Not Completely Restore the Altered Cytokine and Chemokine Milieu in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1965-1974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peschel G, Grimm J, Buechler C, Gunckel M, Pollinger K, Aschenbrenner E, Kammerer S, Jung EM, Haimerl M, Werner J, Müller M, Weigand K. Liver stiffness assessed by shear-wave elastography declines in parallel with immunoregulatory proteins in patients with chronic HCV infection during DAA therapy. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2021;79:541-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saraiva GN, do Rosário NF, Medeiros T, Leite PEC, Lacerda GS, de Andrade TG, de Azeredo EL, Ancuta P, Almeida JR, Xavier AR, Silva AA. Restoring Inflammatory Mediator Balance after Sofosbuvir-Induced Viral Clearance in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:8578051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nabeel MM, Darwish RK, Alakel W, Maher R, Mostafa H, Hashem A, Elbeshlawy M, Abul-Fotouh A, Shousha HI, Saeed Marie M. Changes in Serum Interferon Gamma and Interleukin-10 in Relation to Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy of Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 4: A Pilot Study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:428-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Friedman SL. Regression of Fibrosis Following Hepatitis C Eradication. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2022;18:599-601. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Brakenhoff SM, Verburgh ML, Willemse SB, Baak LC, Brinkman K, van der Valk M. Liver stiffness improvement in hepatitis C patients after successful treatment. Neth J Med. 2020;78:368-375. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, Fontaine H, Pol S. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46:32-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1288] [Cited by in RCA: 1610] [Article Influence: 89.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huynh T, Zhang J, Hu KQ. Hepatitis C Virus Clearance by Direct-acting Antiviral Results in Rapid Resolution of Hepatocytic Injury as Indicated by Both Alanine Aminotransferase and Aspartate Aminotransferase Normalization. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6:258-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhao A, Xiao H, Zhu Y, Liu S, Zhang S, Yang Z, Du L, Li X, Niu X, Wang C, Yang Y, Tian Y. Omentin-1: a newly discovered warrior against metabolic related diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2022;26:275-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rabe K, Lehrke M, Parhofer KG, Broedl UC. Adipokines and insulin resistance. Mol Med. 2008;14:741-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adams-Huet B, Devaraj S, Siegel D, Jialal I. Increased adipose tissue insulin resistance in metabolic syndrome: relationship to circulating adipokines. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2014;12:503-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sitticharoon C, Nway NC, Chatree S, Churintaraphan M, Boonpuan P, Maikaew P. Interactions between adiponectin, visfatin, and omentin in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues and serum, and correlations with clinical and peripheral metabolic factors. Peptides. 2014;62:164-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nassif WM, Amin AI, Hassan ZA, Abdelaziz DH. Changes of serum omentin-1 levels and relationship between omentin-1 and insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C patients. EXCLI J. 2013;12:924-932. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Wójcik K, Jabłonowska E, Omulecka A, Piekarska A. Insulin resistance, adipokine profile and hepatic expression of SOCS-3 gene in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10449-10456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kukla M, Waluga M, Adamek B, Zalewska-Ziob M, Kasperczyk J, Gabriel A, Bułdak RJ, Sobala-Szczygieł B, Kępa L, Ziora K, Żwirska-Korczala K, Surma E, Sawczyn T, Hartleb M. Omentin serum concentration and hepatic expression in chronic hepatitis C patients - together or apart? Pol J Pathol. 2015;66:231-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Eisinger K, Krautbauer S, Wiest R, Karrasch T, Hader Y, Scherer MN, Farkas S, Aslanidis C, Buechler C. Portal vein omentin is increased in patients with liver cirrhosis but is not associated with complications of portal hypertension. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:926-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kukla M, Waluga M, Żorniak M, Berdowska A, Wosiewicz P, Sawczyn T, Bułdak RJ, Ochman M, Ziora K, Krzemiński T, Hartleb M. Serum omentin and vaspin levels in cirrhotic patients with and without portal vein thrombosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2613-2624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. Clinical Practice Guidelines Panel: Chair; EASL Governing Board representative; Panel members. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series(☆). J Hepatol. 2020;73:1170-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 567] [Cited by in RCA: 779] [Article Influence: 155.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yen YH, Kuo FY, Chen CH, Hu TH, Lu SN, Wang JH, Hung CH. Ultrasound is highly specific in diagnosing compensated cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C patients in real world clinical practice. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sigrist RMS, El Kaffas A, Jeffrey RB, Rosenberg J, Willmann JK. Intra-Individual Comparison between 2-D Shear Wave Elastography (GE System) and Virtual Touch Tissue Quantification (Siemens System) in Grading Liver Fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:2774-2782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McPherson S, Hardy T, Dufour JF, Petta S, Romero-Gomez M, Allison M, Oliveira CP, Francque S, Van Gaal L, Schattenberg JM, Tiniakos D, Burt A, Bugianesi E, Ratziu V, Day CP, Anstee QM. Age as a Confounding Factor for the Accurate Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Advanced NAFLD Fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:740-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 81.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Peschel G, Grimm J, Gülow K, Müller M, Buechler C, Weigand K. Chemerin Is a Valuable Biomarker in Patients with HCV Infection and Correlates with Liver Injury. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li XP, Zeng S, Wang M, Wu XP, Liao EY. Relationships between serum omentin-1, body fat mass and bone mineral density in healthy Chinese male adults in Changsha area. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37:991-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Negro F. Facts and fictions of HCV and comorbidities: steatosis, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases. J Hepatol. 2014;61:S69-S78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rau M, Buggisch P, Mauss S, Boeker KHW, Klinker H, Müller T, Stoehr A, Schattenberg JM, Geier A. Prognostic impact of steatosis in the clinical course of chronic HCV infection-Results from the German Hepatitis C-Registry. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0264741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang Q, Chen S, Ke Y, Li Q, Shen C, Ruan Y, Wu K, Hu J, Liu S. Association of circulating omentin level and metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1073498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hedskog C, Parhy B, Chang S, Zeuzem S, Moreno C, Shafran SD, Borgia SM, Asselah T, Alric L, Abergel A, Chen JJ, Collier J, Kapoor D, Hyland RH, Simmonds P, Mo H, Svarovskaia ES. Identification of 19 Novel Hepatitis C Virus Subtypes-Further Expanding HCV Classification. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:ofz076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Asselah T, Hassanein T, Waked I, Mansouri A, Dusheiko G, Gane E. Eliminating hepatitis C within low-income countries - The need to cure genotypes 4, 5, 6. J Hepatol. 2018;68:814-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hnatyszyn HJ. Chronic hepatitis C and genotyping: the clinical significance of determining HCV genotypes. Antivir Ther. 2005;10:1-11. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Ghadir MR, Riahin AA, Havaspour A, Nooranipour M, Habibinejad AA. The relationship between lipid profile and severity of liver damage in cirrhotic patients. Hepat Mon. 2010;10:285-288. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Jiang M, Liu F, Xiong WJ, Zhong L, Xu W, Xu F, Liu YB. Combined MELD and blood lipid level in evaluating the prognosis of decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1397-1401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Valkov I, Ivanova R, Alexiev A, Antonov K, Mateva L. Association of Serum Lipids with Hepatic Steatosis, Stage of Liver Fibrosis and Viral Load in Chronic Hepatitis C. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:OC15-OC20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Christodoulatos GS, Antonakos G, Karampela I, Psallida S, Stratigou T, Vallianou N, Lekka A, Marinou I, Vogiatzakis E, Kokoris S, Papavassiliou AG, Dalamaga M. Circulating Omentin-1 as a Biomarker at the Intersection of Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Occurrence and Cardiometabolic Risk: An Observational Cross-Sectional Study. Biomolecules. 2021;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Alcelik A, Tosun M, Ozlu MF, Eroglu M, Aktas G, Kemahli E, Savli H, Yazici M. Serum levels of omentin in end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012;35:511-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Levey AS, Perrone RD, Madias NE. Serum creatinine and renal function. Annu Rev Med. 1988;39:465-490. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Baranova A, Jarrar MH, Stepanova M, Johnson A, Rafiq N, Gramlich T, Chandhoke V, Younossi ZM. Association of serum adipocytokines with hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Digestion. 2011;83:32-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Buechler C, Wanninger J, Neumeier M. Adiponectin, a key adipokine in obesity related liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2801-2811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Udomsinprasert W, Honsawek S, Poovorawan Y. Adiponectin as a novel biomarker for liver fibrosis. World J Hepatol. 2018;10:708-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | Buechler C, Haberl EM, Rein-Fischboeck L, Aslanidis C. Adipokines in Liver Cirrhosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Im GY, Dieterich DT. Direct-acting antiviral agents in patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:727-765. [PubMed] |