Published online Dec 27, 2023. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1307

Peer-review started: July 28, 2023

First decision: September 14, 2023

Revised: October 25, 2023

Accepted: December 4, 2023

Article in press: December 4, 2023

Published online: December 27, 2023

Processing time: 150 Days and 0.9 Hours

Liver resection is the mainstay for a curative treatment for patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), also in elderly population. Despite this, the evaluation of patient condition, liver function and extent of disease remains a demanding process with the aim to reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality.

To identify new perioperative risk factors that could be associated with higher 90- and 180-d mortality in elderly patients eligible for liver resection for HCC considering traditional perioperative risk scores and to develop a risk score.

A multicentric, retrospective study was performed by reviewing the medical records of patients aged 70 years or older who electively underwent liver resection for HCC; several independent variables correlated with death from all causes at 90 and 180 d were studied. The coefficients of Cox regression proportional-hazards model for six-month mortality were rounded to the nearest integer to assign risk factors' weights and derive the scoring algorithm.

Multivariate analysis found variables (American Society of Anesthesiology score, high rate of comorbidities, Mayo end stage liver disease score and size of biggest lesion) that had independent correlations with increased 90- and 180-d mortality. A clinical risk score was developed with survival profiles.

This score can aid in stratifying this population in order to assess who can benefit from surgical treatment in terms of postoperative mortality.

Core Tip: To support the decision-making process in elderly patient with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and understand who can benefit from surgical treatment in terms of postoperative mortality, we analyzed data from 11 hepato-biliary centers during a 10-years period. A multivariate analysis was performed to find variables (American Society of Anesthesiology score, high rate of comorbidities, Mayo end stage liver disease score and size of biggest lesion) that had independent correlations with increased 90‐ and 180‐d mortality. The evaluation of elderly patients who underwent liver resection for HCC need to be supported by any form of possible analysis of risk.

- Citation: Conticchio M, Inchingolo R, Delvecchio A, Ratti F, Gelli M, Anelli MF, Laurent A, Vitali GC, Magistri P, Assirati G, Felli E, Wakabayashi T, Pessaux P, Piardi T, di Benedetto F, de'Angelis N, Briceño J, Rampoldi A, Adam R, Cherqui D, Aldrighetti LA, Memeo R. Peri-operative score for elderly patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2023; 15(12): 1307-1314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v15/i12/1307.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v15.i12.1307

The life expectancy of the population has increased in recent years, and this led to an increased rate of malignant disease in elderly population[1,2]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) became even more frequent in elderly population[3,4].

According to current guidelines liver resection, ablation and liver transplant are still the mainstay treatments for HCC.

Liver resection presented better overall and disease-free survival than other curative treatments[5]. Despite this, liver resection presented a significant risk postoperative morbidity and mortality.

The approach of liver disease in elderly population needed of an accurate stratification of patients at risk, with the involvement of multidisciplinary preoperative assessment.

The aim of our study was to analyze a population of elderly patients who underwent liver resection for HCC, to investigate the possible presence of risk predictors of postoperative mortality at 90 and 180 d.

A multicentric, retrospective cohort study was carried out by reviewing the medical records of patients aged > 70 years or over undergoing liver resection for HCC from January 2009 to January 2019. We evaluated all preoperative independent variables linked with patients (demographics data), with lesion (number and size, calculated on the preoperative imaging) and preoperative clinical assessment in eligible patients. The primary endpoint was to define 90 d and 180 d mortality rate. The second one was to explore the association among variables and post operative mortality rate.

All analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 16 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, Tex). Data are reported as means (standard deviations) for continuous variables or numbers (percentages) of patients for categorical variables. Six-month follow-up was chosen to analyze at least 20 fatal events after the surgery. Associations between baseline pre-operative variables with six-month mortality were evaluated using a univariate Cox proportional-hazards model. A score point system was derived from the multivariable Cox proportional-hazards model including univariate predictors with P < 0.05. For a dichotomous risk factor, the estimated regression coefficient was rounded to the nearest integer. For a non-dichotomous risk factor, continuous or discrete, the estimated regression coefficient was multiplied by observed values, rounded to the nearest integer and rescaled to assign zero points to the lowest risk-category. Hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95%CI were reported. The discriminative ability of the models was assessed using the Harrell’s concordance index (C-index). Patients were stratified into three groups of risk by the estimated six-month mortality probability (low-risk < 5%, mid-risk 5%-10%, and high-risk > 10%). The cumulative mortality was displayed using Kaplan-Meier estimates with comparison between curves based on the Log-Rank statistic. The score was internally validated by resampling 1000 bootstrap replications. The bias was calculated as the difference between estimation and the mean of the bootstrap sample. Theoretical profiles were constructed by combining variables of the final model as well as a risk score for death in the period. The cut off of 6 mo as final follow up has been chosen to obtain an appropriate number of events, but its significance was validated at 3 mo. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 429 patients, who underwent liver resection for HCC were included (Table 1). The majority of patients were male (n = 319, 74.3%, and 110 females, 25.7%), aged ≥ 70 years (mean of 75.3 ± 4.1 years); 20 deaths (4.7%) occurred up to 180 d after surgery, as shown in Table 1.

| All | Alive at 180 d | Death at 180 d | HR | P value | ||||

| N | n = 429 | N | n = 409 | N | n = 20 | |||

| Age, yr | 429 | 75.3 ± 4.1 | 409 | 75.3 ± 4.1 | 20 | 76.9 ± 4.9 | 1.52 (0.94-2.47) | 0.086 |

| Male | 429 | 319 (74.4) | 409 | 306 (74.8) | 20 | 13 (65.0) | 0.61 (0.24-1.54) | 0.296 |

| BMI | 429 | 26.9 ± 3.5 | 409 | 26.9 ± 3.6 | 20 | 26.9 ± 0.9 | 0.97 (0.52-1.82) | 0.921 |

| ASA score | 429 | 2.60 ± 0.50 | 409 | 2.59 ± 0.50 | 20 | 2.90 ± 0.31 | 4.49 (1.47-13.74) | 0.008 |

| Comorbidity > 2 | 429 | 142 (33.1) | 409 | 129 (31.5) | 20 | 13 (65.0) | 3.92 (1.56-9.82) | 0.004 |

| HBV | 429 | 80 (18.6) | 409 | 80 (19.6) | 20 | 0 (0.0) | - | - |

| HCV | 429 | 217 (50.6) | 409 | 210 (51.3) | 20 | 7 (35.0) | 0.51 (0.2-1.28) | 0.151 |

| ALD | 429 | 60 (14.0) | 409 | 56 (13.7) | 20 | 4 (20.0) | 1.58 (0.53-4.72) | 0.415 |

| Others | 429 | 72 (16.8) | 409 | 63 (15.4) | 20 | 9 (45.0) | 4.3 (1.78-10.37) | 0.001 |

| F4 cirrhosis | 429 | 178 (41.5) | 409 | 173 (42.3) | 20 | 5 (25.0) | 0.46 (0.17-1.27) | 0.134 |

| CHILD A | 429 | 370 (86.2) | 409 | 353 (86.3) | 20 | 17 (85.0) | 0.92 (0.27-3.13) | 0.891 |

| MELD score | 429 | 7.4 ± 2.1 | 409 | 7.4 ± 2.0 | 20 | 8.9 ± 2.7 | 1.25 (1.09-1.44) | 0.001 |

| Albumin | 382 | 3.80 ± 0.60 | 367 | 3.80 ± 0.60 | 15 | 3.71 ± 0.77 | 0.75 (0.33-1.73) | 0.504 |

| Bilirubin | 424 | 1.05 ± 0.64 | 404 | 1.05 ± 0.64 | 20 | 0.99 ± 0.54 | 0.81 (0.37-1.76) | 0.587 |

| Creatinin | 425 | 1.03 ± 0.36 | 405 | 1.02 ± 0.36 | 20 | 1.17 ± 0.42 | 2.55 (0.9-7.2) | 0.077 |

| INR | 422 | 1.20 ± 0.23 | 402 | 1.20 ± 0.23 | 20 | 1.17 ± 0.28 | 0.51 (0.07-3.8) | 0.508 |

| AST | 424 | 68 ± 61 | 405 | 69 ± 61 | 19 | 48 ± 41 | 0.92 (0.85-1) | 0.045 |

| ALT | 201 | 51 ± 80 | 182 | 52 ± 82 | 19 | 41 ± 48 | 0.98 (0.91-1.05) | 0.540 |

| GGT | 192 | 145 ± 218 | 174 | 145 ± 218 | 18 | 146 ± 228 | 1 (0.98-1.02) | 0.958 |

| Platelets | 425 | 191 ± 92 | 406 | 191 ± 92 | 19 | 177 ± 85 | 0.98 (0.93-1.04) | 0.509 |

| Number of lesions | 429 | 1.09 ± 0.30 | 409 | 1.09 ± 0.31 | 20 | 1.05 ± 0.22 | 0.54 (0.08-3.77) | 0.531 |

| Size of biggest lesion (mm) | 429 | 33 ± 10 | 409 | 32 ± 10 | 20 | 37 ± 13 | 1.26 (1.01-1.58) | 0.043 |

| Bilobar lesion | 429 | 8 (1.9) | 409 | 8 (2.0) | 20 | 0 (0.0) | - | - |

| Preop treatment | 429 | 53 (12.4) | 409 | 50 (12.2) | 20 | 3 (15.0) | 1.24 (0.36-4.23) | 0.732 |

| Major HTC | 429 | 56 (13.1) | 409 | 55 (13.4) | 20 | 1 (5.0) | 0.34 (0.05-2.56) | 0.297 |

Two hundred fifty-seven patients, 60% presented an American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score III-IV, and the median range of Mayo end stage liver disease (MELD) score was 7 (7.4 ± 2.1). Roughly one third of patients was affected by more of 2 comorbidities (n = 142, 33.1%). Most patients presented a single, unilobar lesion (n = 421, 98%). Most of patients underwent to a minor hepatectomy, while only 54 patients (13.1%) underwent to a major hepatectomy, according to Brisbane classification.

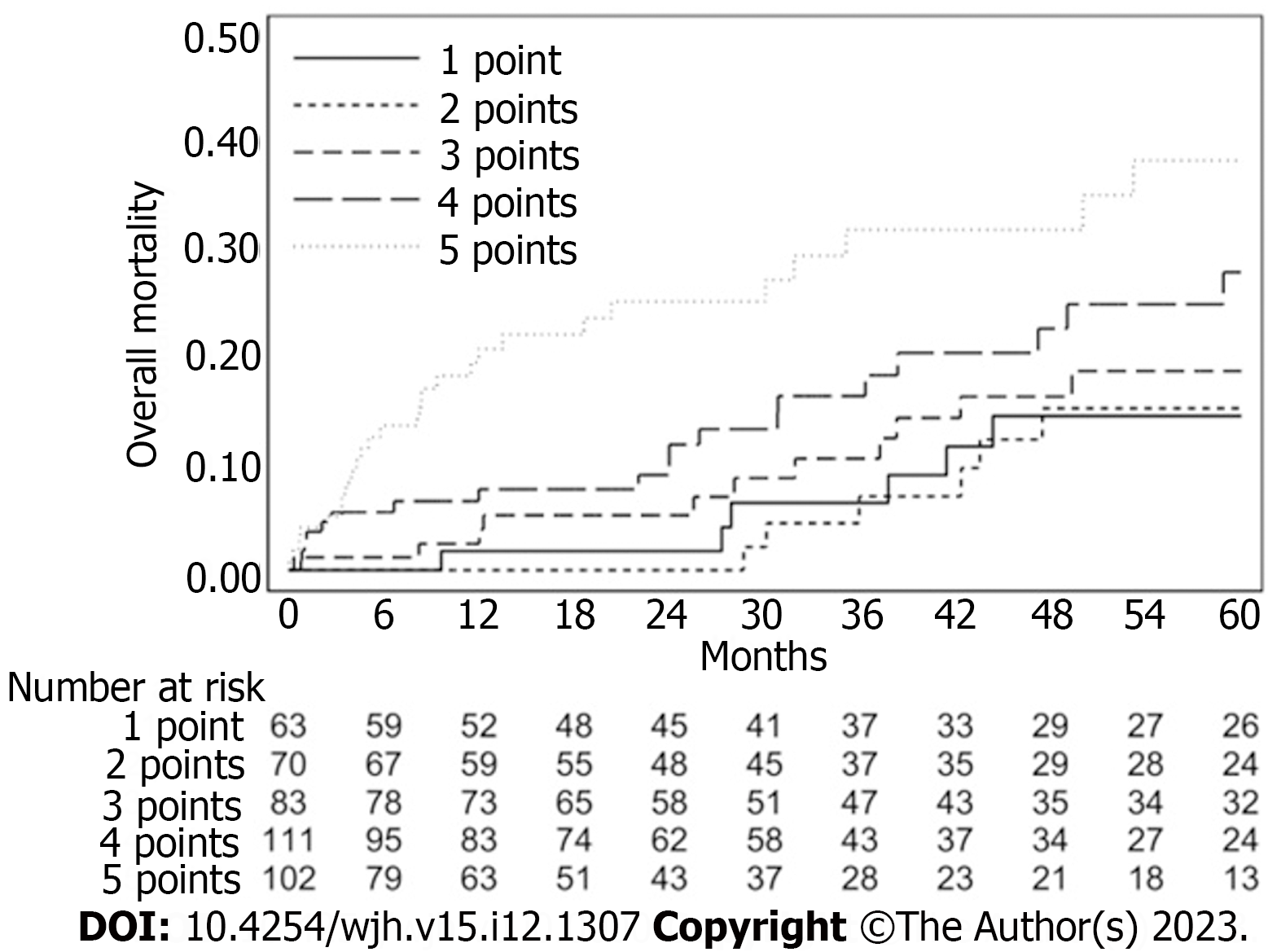

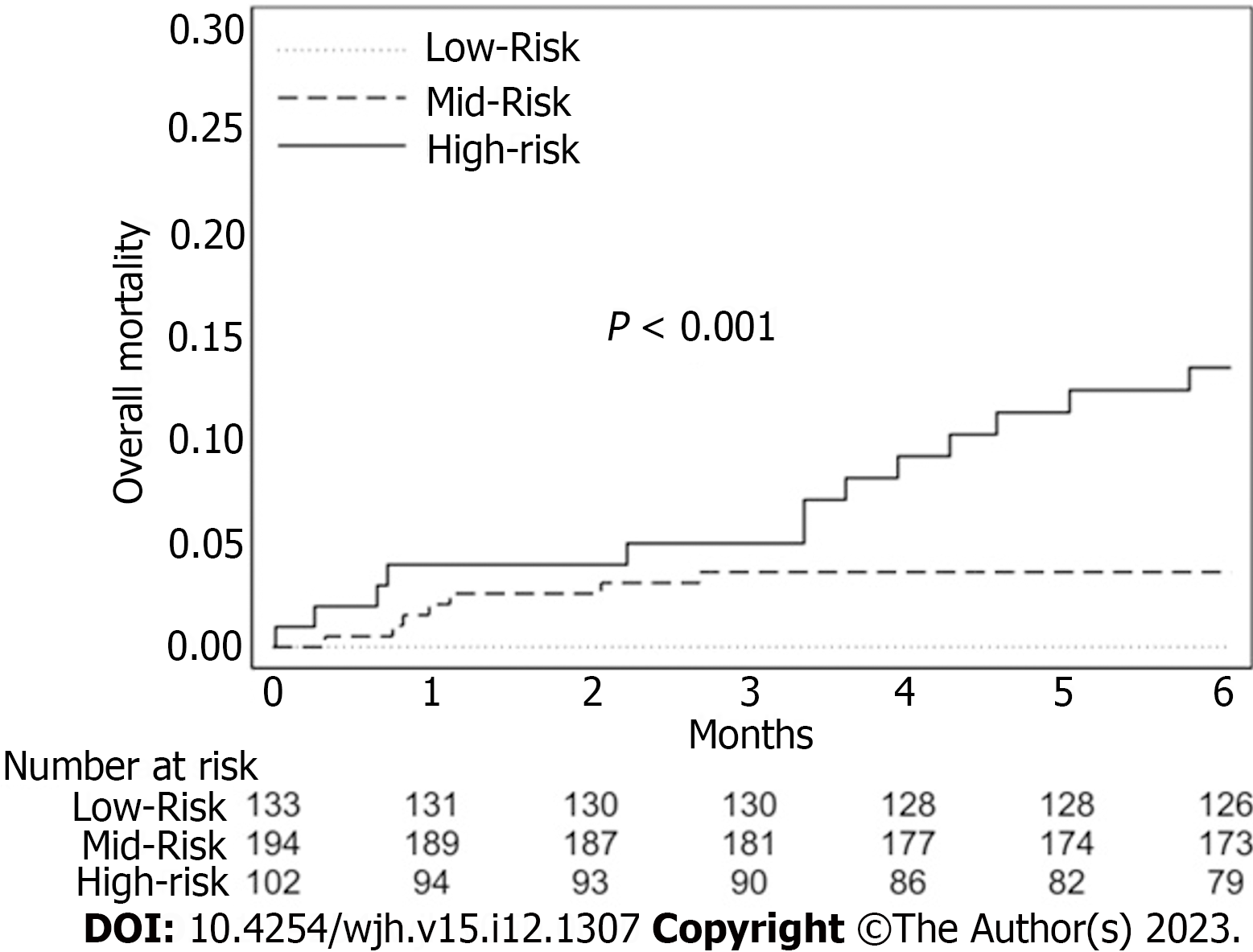

The overall survival curve calculated by the Kaplan–Meier estimator is shown in Figure 1. The ASA score, MELD score, the presence of Comorbidities > 2 and the size of the biggest lesion presented in the univariate analysis an HR greater than 1, as shown in Table 1. They are used as predictor factors in the multivariate analysis (Table 2). Table 3 showed a score system which provides a balanced weight for each variable. Combining the four variables we obtained different profiles of patients with a different preoperative risk, based on personal score, groupable in a low-risk (< 5% at 6 mo), mid-risk (5%-10% at 6 mo) and high-risk class (> 10% at 6 mo) (Table 4 and Figure 2).

| Beta | HR | P value | |

| ASA score | 1.189 | 3.28 (1.04-10.34) | 0.042 |

| Comorbidity 2 | 1.071 | 2.92 (1.14-7.45) | 0.025 |

| MELD | 0.202 | 1.22 (1.06-1.41) | 0.005 |

| Size of largest lesion | 0.046 | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | 0.034 |

| C-index = 0.807 | - | - | - |

| Values | Points | |

| ASA score | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | |

| 3 | 2 | |

| 4 | 3 | |

| Comorbidity > 2 | Yes | 1 |

| MELD | < 8 | 0 |

| 8-12 | 1 | |

| > 12 | 2 | |

| Size of largest lesion (mm) | ≤ 10 | 0 |

| 10-32 | 1 | |

| > 32 | 2 | |

| Max score | 8 |

| Score | Number and prevalence, n (%) | Three-month mortality, % | Six-month mortality, % |

| ≥ 2 vs ≤ 1 | 366 (85.3) vs 63 (14.7) | 3.3 vs 0.0 | 5.7 vs 0.0 |

| ≥ 3 vs ≤ 2 | 296 (69.0) vs 133 (31.0) | 4.1 vs 0.0 | 7.0 vs 0.0 |

| ≥ 4 vs ≤ 3 | 213 (49.7) vs 216 (50.3) | 5.3 vs 0.5 | 9.3 vs 0.5 |

| ≥ 5 vs ≤ 4 | 102 (23.8) vs 327 (76.2) | 5.0 vs 2.2 | 13.6 vs 2.2 |

| ≥ 6 vs ≤ 5 | 28 (6.5) vs 401 (93.5) | 11.3 vs 2.3 | 22.9 vs 3.6 |

Figure 2 showed the curves of six-month mortality probability, according to the different profile created on various score. The rate of mortality probability significantly increased from patients with score 2 to patients with score 6: Patients with a score ≥ 2 presented a 5.7% of mortality, patients with a score ≥ 3 presented a 7%, patients with a score ≥ 4 showed a 9.3% of mortality, patients with a score ≥ 5 showed a 13.6%, patients with a score ≥ 6 presented 22.9% of mortality.

We performed an Internal validation using a bootstrapping technique with 1000 resamples, the derived score point system had good discrimination as 0.803 of the Harrell C-Index (bootstrap 95%CI 0.741-0.875). The bias of the estimated risk assigned to 1 point of the score, as the difference between coefficient estimation in the derivation model (0.875) and the mean of the bootstrap sample (0.888), it was negligible (-0.013).

The present study observed a population of elderly patients (≥ 70 years) who underwent liver resection for HCC, and it showed that a simple preoperative score, resulting from the evaluation of presence and degree of ASA score, MELD score, the presence of more than 2 comorbidities and the size of the biggest lesion, can predict 90 d and 180 d mortality rate.

The process of ‘aging society’ resulted in an increasing rate of surgical oncological elderly patients and it made necessary to provide an accurate preoperative assessment to optimize the choice of the best possible treatment. Liver resection represented the treatment of choice for resectable HCC, even in elderly population[6-9]. Age itself should not be a contraindication to liver resection in treatment of HCC, but this population needed a more accurate selection and preoperative evaluation of benefits and drawback.

The assessment of liver function needed to be linked with the identification of modifiable and not modifiable risk factors to improve surgical outcomes. There were several predictive of 30 d mortality after liver resection for HCC[10-13]. MELD score was often considered a significant parameter, as well in our study where this score was ranged in 3 degrees with a different impact on final sum. Conversely Lee et al[14] in a nationwide cohort study recognized the Platelet-Albumin-Bilirubin score had an higher sensitivity and specificity than MELD or Albumin-Bilirubin score[15].

With the aim to better explore the concept of ‘frailty’ in this population also the ASA score gained more relevance. In our results an ASA score of 1-2 or 3-4 can weight in a different significantly way on the final score and so have impact on the post operative mortality probability. Not only the evaluation of the degree of pathological physical state, but also the presence of more of 2 comorbidities resulted significant as risk predictor in our score. The limit was represented by not knowing the type of comorbidity which made impossible to optimize the stratification. Preoperative evaluation of the physiological age could be more useful in predicting risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality than chronological age[16,17], but several external validation of comprehensive score are needed.

As previously reported the size of largest tumor was a useful factor to predict prognostic outcomes after liver resection for HCC[13,18,19]. Also our results showed in univariate and multivariate analysis how an increasing size could be a risk factor on postoperative mortality. In the setting of liver disease almost completely represented by a single nodule of HCC, a size > 32 mm could impact on postoperative mortality risk as a MELD score > 12. The idea of the importance of morphological tumor data was yet explored by Mazzaferro[18] with ‘Metroticket paradigm’ before, and ‘Up to7 criteria’ after, more useful in the context of liver transplantation, but it had represented the substrate for comprehensive measures as reported by Tokumitsu et al[12] with its NxS score which provide a cut off value of tumor burden to predict the prognosis following hepatectomies for HCC[12]. Despite this, prognosis of HCC was more complex than other solid tumors because it depended not only from tumor burden but also from liver function reserve.

ASA score, MELD score, the presence of more than 2 comorbidities and the size of the lesion were all non-modifiable factor. Our work underlined how the process of decision making could be delicate in elderly patients with HCC. The association of evaluation of liver (functional and oncological) disease and the physiological age of patients needed to be assessed before surgery[19-20] to better stratifying patients at risk and to implement preoperative and postoperative programs of rehabilitation which could bridge the gap of physiopathological state[21].

However, this study had some limitations. First of all, because of its retrospective nature, there was a possibility of an unavoidable selection bias. Secondly, the surgical procedures included were laparoscopic and open approach without considering their different impact on the postoperative outcomes. In addition, our aim was to evaluate 90 and 180 d mortality but another key point was represented by postoperative complications and their correlations with preoperative and intraoperative data. This could be the focus for future works.

In conclusion, our score resulted from granular evaluation of possible risk factors for the postoperative mortality at 90 d and 180 d in elderly patients resected for HCC.

It would be a simple and useful tool to provide a better cognition of patients who could benefit of liver resection and to improve 180 d mortality.

Liver resection represented one of the mainstay treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The approach of liver disease in elderly population needed of an accurate stratification of patients at risk, with the involvement of multidisciplinary preoperative assessment.

Liver resection is burdened by a variable rate of postoperative morbidity and mortality. Elderly patients represented more often the major rate of patients who underwent liver resection for HCC. This aspect makes mandatory an accurate preoperative assessment and a specific evaluation of potential postoperative risk.

The aim of our study was to analyze a population of elderly patients who underwent liver resection for HCC, to investigate the possible presence of risk predictors of postoperative mortality at 90 and 180 d.

Associations between baseline pre-operative variables with six-month mortality were evaluated using a unit-variate Cox proportional-hazards model. A score point system was derived from the multi-variable Cox proportional-hazards model.

The American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score, Mayo end stage liver disease score, the presence of comorbidities > 2 and the size of the biggest lesion are included in the stratification of the score. Combining the four variables we obtained different profiles of patients with a different preoperative risk at 6 mo: Low-risk < 5%, mid-risk 5%-10% and high-risk class > 10%.

This score can aid in stratifying this population in order to assess who can benefit from surgical treatment in terms of postoperative mortality.

Randomized controlled studies are needed to better explore these results.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fernández-Placencia RM, Peru; Li YW, China S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Marosi C, Köller M. Challenge of cancer in the elderly. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sav A, McMillan SS, Akosile A. Burden of Treatment among Elderly Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20516] [Article Influence: 2051.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (20)] |

| 4. | Petrick JL, Florio AA, Znaor A, Ruggieri D, Laversanne M, Alvarez CS, Ferlay J, Valery PC, Bray F, McGlynn KA. International trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, 1978-2012. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:317-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 78.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, Raoul JL, Schirmacher P, Vilgrain V; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5593] [Cited by in RCA: 6066] [Article Influence: 866.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Kaibori M, Yoshii K, Yokota I, Hasegawa K, Nagashima F, Kubo S, Kon M, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Kudo M, Kumada T, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Matsuyama Y, Takayama T, Kokudo N; Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Impact of Advanced Age on Survival in Patients Undergoing Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Report of a Japanese Nationwide Survey. Ann Surg. 2019;269:692-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758-2765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1195] [Cited by in RCA: 1319] [Article Influence: 82.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Conticchio M, Inchingolo R, Delvecchio A, Laera L, Ratti F, Gelli M, Anelli F, Laurent A, Vitali G, Magistri P, Assirati G, Felli E, Wakabayashi T, Pessaux P, Piardi T, di Benedetto F, de'Angelis N, Briceño J, Rampoldi A, Adam R, Cherqui D, Aldrighetti LA, Memeo R. Radiofrequency ablation vs surgical resection in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Milan criteria. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:2205-2218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Conticchio M, Delvecchio A, Ratti F, Gelli M, Anelli FM, Laurent A, Vitali GC, Magistri P, Assirati G, Felli E, Wakabayashi T, Pessaux P, Piardi T, Di Benedetto F, de'Angelis N, Javier Briceno DF, Rampoldi AG, Adam R, Cherqui D, Aldrighetti L, Memeo R. Laparoscopic surgery versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of single hepatocellular carcinoma ≤3 cm in the elderly: a propensity score matching analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2022;24:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Takagi K, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, Nobuoka D, Kuise T, Fushimi T, Fujiwara T, Yagi T. Preoperative Controlling Nutritional Status Score Predicts Mortality after Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2019;36:226-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shen J, Tang L, Zhang X, Peng W, Wen T, Li C, Yang J, Liu G. A Novel Index in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients After Curative Hepatectomy: Albumin to Gamma-Glutamyltransferase Ratio (AGR). Front Oncol. 2019;9:817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tokumitsu Y, Shindo Y, Matsui H, Matsukuma S, Nakajima M, Suzuki N, Takeda S, Wada H, Kobayashi S, Eguchi H, Ueno T, Nagano H. Utility of scoring systems combining the product of tumor number and size with liver function for predicting the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:3903-3913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moris D, Shaw BI, Ong C, Connor A, Samoylova ML, Kesseli SJ, Abraham N, Gloria J, Schmitz R, Fitch ZW, Clary BM, Barbas AS. A simple scoring system to estimate perioperative mortality following liver resection for primary liver malignancy-the Hepatectomy Risk Score (HeRS). Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2021;10:315-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee SK, Song MJ, Kim SH, Park M. Comparing various scoring system for predicting overall survival according to treatment modalities in hepatocellular carcinoma focused on Platelet-albumin-bilirubin (PALBI) and albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Okinaga H, Yasunaga H, Hasegawa K, Fushimi K, Kokudo N. Short-Term Outcomes following Hepatectomy in Elderly Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Analysis of 10,805 Septuagenarians and 2,381 Octo- and Nonagenarians in Japan. Liver Cancer. 2018;7:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tokumitsu Y, Sakamoto K, Tokuhisa Y, Matsui H, Matsukuma S, Maeda Y, Sakata K, Wada H, Eguchi H, Ogihara H, Fujita Y, Hamamoto Y, Iizuka N, Ueno T, Nagano H. A new prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after curative hepatectomy. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:4411-4422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tokumitsu Y, Tamesa T, Matsukuma S, Hashimoto N, Maeda Y, Tokuhisa Y, Sakamoto K, Ueno T, Hazama S, Ogihara H, Fujita Y, Hamamoto Y, Oka M, Iizuka N. An accurate prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma patients after curative hepatectomy. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:944-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mazzaferro V. Results of liver transplantation: with or without Milan criteria? Liver Transpl. 2007;13:S44-S47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McCorkle R, Strumpf NE, Nuamah IF, Adler DC, Cooley ME, Jepson C, Lusk EJ, Torosian M. A specialized home care intervention improves survival among older post-surgical cancer patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1707-1713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kaibori M, Matsushima H, Ishizaki M, Kosaka H, Matsui K, Ogawa A, Yoshii K, Sekimoto M. Perioperative Geriatric Assessment as A Predictor of Long-Term Hepatectomy Outcomes in Elderly Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Melloul E, Hübner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong CH, Garden OJ, Farges O, Kokudo N, Vauthey JN, Clavien PA, Demartines N. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Liver Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World J Surg. 2016;40:2425-2440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |