Published online Apr 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i4.846

Peer-review started: July 30, 2021

First decision: September 29, 2021

Revised: October 8, 2021

Accepted: March 25, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Published online: April 27, 2022

Processing time: 265 Days and 18.4 Hours

Infection of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) stent is a rare and serious complication that most commonly occurs during TIPS creation and revision. Patients typically present with recurrent bacteremia due to shunt occlusion or vegetation. To date there are approximately 58 cases reported. We present a patient diagnosed with late polymicrobial TIPS infection five years following TIPS creation.

A 63-year-old female status-post liver transplant with recurrent cirrhosis and portal hypertension presented with sepsis and recurrent extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Escherichia coli bacteremia. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an occluded TIPS with thrombus extension into the distal right portal vein, and focal thickening of the cecum and ascending colon. Colonoscopy revealed patchy ulcers in these areas with histopathology demonstrating ulcerated colonic mucosa with fibrinopurulent exudate. Shunt thrombectomy and revision revealed infected-appearing thrombus. Patient initially cleared her infection with antibacterial therapy and TIPS revision; however, soon after, she developed Enterobacter cloacae bacteremia and Candida glabrata and C. albicans fungemia with recurrent TIPS thrombosis. She remained on antifungal therapy indefinitely and later developed vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium with recurrent TIPS thrombosis. The option of liver re-transplant for removal of the infected TIPS was not offered given her critical illness and complex shunt anatomy. The patient became intolerant to linezolid and elected hospice care.

Clinicians should be aware that TIPS superinfection may occur as long as five years following TIPS creation in an immunocompromised patient.

Core Tip: Polymicrobial transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) infection may occur in an immunocompromised patient many years following TIPS creation. Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with TIPS infection, it is important to consider this diagnosis early in a patient with recurrent septicemia, even without recent TIPS creation or revision. Early shunt thrombectomy is important for source control and optimization of antibiotic penetrance of the TIPS.

- Citation: Perez IC, Haskal ZJ, Hogan JI, Argo CK. Late polymicrobial transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt infection in a liver transplant patient: A case report. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(4): 846-853

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i4/846.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i4.846

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) creation is a routine therapy for patients with complications of portal hypertension such as refractory ascites or variceal hemorrhage[1]. Endotipsitis is a rare endovascular infection of a TIPS with a prevalence of approximately 1% and mortality rate of approximately 32%[2-4]. A rare but challenging complication of endotipsitis is persistent bacteremia following TIPS creation and revision. Early cases of TIPS infection, categorized as an infection within 120 days of TIPS creation, are commonly associated with gram-positive bacteria[4]. In the USA the use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to TIPS creation is routinely practiced, and according to the American Society of Interventional Radiology is considered a class IIB recommendation[2,5]. However, there are strict indications based on the guidelines by the British Society of Gastroenterology, which strongly recommend prophylactic antibiotics only for TIPS shunt for variceal bleeding, long/complex procedures, or in a patient with a previous biliary surgery or instrumentation[6].

TIPS stent colonization is believed to be secondary to lack of graft endothelization with the highest mortality rates associated with Staphylococcus and Candida species[2-4,7]. These microorganisms are difficult to treat given their ability to form biofilms, as can be seen in other endovascular infections such as prosthetic valve endocarditis[7,8]. Tacrolimus, a immunosuppressive medication prescribed to this patient, has been associated with decreased epithelization in animal and in vivo studies and therefore may further increase the risk of TIPS stent colonization in a patient[9,10]. This case report presents a rare event of polymicrobial TIPS infection occurring five years following TIPS creation in an immunosuppressed patient status post liver transplantation for hepatitis C cirrhosis. Additionally, polymicrobial endotipsitis cases were identified through PubMed to provide an updated overview of treatment courses and associated health outcomes.

A 63-year-old female presented with sepsis and recurrent extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteremia.

Our patient initially presented to her local hospital with hypotension and sepsis in late August 2019 and completed a 10-d course of ertapenem while hospitalized for E. coli bacteremia. She presented locally with similar symptoms a few days after discharge from the initial admission and was found to have recurrent E. coli bacteremia with the identical susceptibility pattern. Imaging demonstrated TIPS occlusion, and the patient was transferred to our institution with recurrent E. coli bacteremia from an unidentified source.

Our patient with a MELD-Na score of 23 underwent orthotopic liver transplantation in 2009 for hepatitis C cirrhosis. Her transplant course was complicated by recurrent hepatitis C infection resulting in bridging fibrosis/early cirrhosis despite viral eradication in 2011. She eventually developed portal hypertension related to a non-occlusive portal vein thrombosis and anastomotic stenosis of the hepatic vein and inferior vena cava. In 2014, she suffered acute gastric variceal bleeding and underwent semi-urgent treatment with balloon-occluded anterograde obliteration of a gastrorenal shunt and TIPS creation with a self-expanding poly-tetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE)–covered stent-graft.

Medical history included hepatitis C, gastric varices, hypertension, well-controlled diabetes mellitus type 2, iron deficiency anemia and fibromyalgia. Family history included hypertension, lung cancer, and prostate cancer.

The patient was afebrile and displayed right upper abdominal tenderness.

Laboratory findings included hemoglobin 8.6 (12-16 g/dL) (baseline of approximately 9-10), white blood cell (WBC) 5.39 (4-11 × 103/µL), platelets 89 (150-450 × 103/µL), alanine transferase 16 (< 55 U/L), aspartate transferase 19 (< 35 U/L), total bilirubin 0.5 (0.3-1.2 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase 88 (40-150 U/L) and creatinine 1.2 (0.7-1.3 mg/dL). Gastrointestinal pathogens panel polymerase chain reaction was negative for enteroaggregative E. coli, enteropathogenic E. coli, enterotoxigenic E. coli, shiga-like toxin-producing E. coli, E. coli O157, and shigella/enteroinvasive E. coli. Histopathology of cecum and ascending colon biopsies obtained a few days prior revealed extensive ulcerated colonic mucosa with fibrinopurulent exudates, consistent with active colitis. There was no evidence of cytomegalovirus associated inclusion bodies, microorganisms, granulomas, or malignancy. Bacterial culture of the extracted thrombus (Figure 1) during thrombectomy did not grow any organisms. Urine analysis showed no bacteria and rare white blood cells per high power field with no growth on culture.

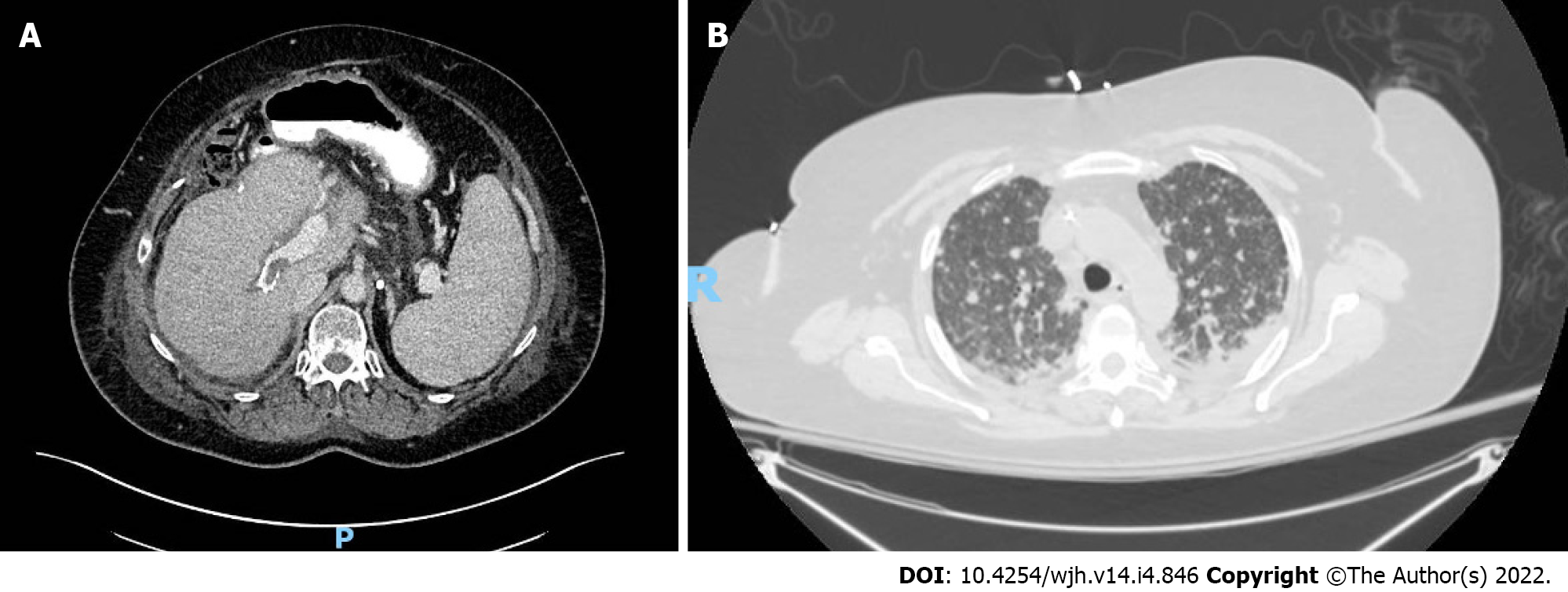

Thickening of the cecum and ascending colon, and TIPS occlusion that extended into the distal right portal vein were noted on abdominal computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2A). Magnetic resonance imaging did not show significant hepatic biliary dilatation or biliary leak. Chest CT suggested multiple pulmonary septic emboli. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) obtained a few days prior showed mild reduced systolic ejection fraction and no obvious vegetations, though aortic, tricuspid, and pulmonic valves were not well visualized due to restricted patient mobility and excessive abdominal air.

The patient was diagnosed with a late TIPS infection.

She underwent TIPS thrombectomy, venoplasty, and placement of a new Wallstent coaxial uncovered metallic stent at the portal end of the TIPS to extend the intraportal leading end of the shunt into a larger caliber portal vein, as the originally entered portal vein was small in caliber and formed an inflow narrowing into the TIPS at the leading edge of the PTFE-coated self-expanding stent. Anticoagulation after TIPS revision was not considered in this patient as she did not have a primary hypercoagulable disorder, and the flow in the shunt was brisk and was rendered clean by thrombectomy and clot extraction. She was discharged on a 6-wk course of IV ertapenem (1 g once daily). Patient successfully cleared her E. coli bacteremia.

Two and a half months later, our patient presented with a headache and was treated for Enterobacter cloacae and Candida glabrata septicemia. Vital signs were notable for fever (38.2℃) and tachycardia (114 bpm). Labs included hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL, WBC 4.34 × 103/µL, platelets 70 × 103/µL, alanine transferase < 6 U/L, aspartate transferase 33 U/L, and creatinine 0.9 mg/dL. Abdominal CT showed a new non-occlusive thrombus in the mid-TIPS and a right ovarian vein clot. Repeat shunt thrombectomy and revision was performed. Histopathology of the extracted thrombus confirmed Candida species, and C. glabrata and C. albicans grew in blood cultures. Additional infectious workup included a TTE that was non-revealing. A 6-wk course of IV ertapenem (1 g once daily) and IV micafungin (150 mg daily) was initiated at discharge.

Four weeks later she developed acute dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain and was readmitted with hypoxemic respiratory failure. TTE revealed grade 1 diastolic dysfunction without vegetation. Chest CT revealed numerous bilateral pulmonary nodules with diffuse ground-glass and interstitial opacities (Figure 2B). Blood cultures once again grew C. glabrata and C. albicans, and bronchoalveolar lavage grew Candida species. Given suspicion for refractory intravascular Candida infection, therapy was escalated to IV amphotericin (300 mg daily) and oral flucytosine (1000 mg twice a day). Balloon sweep of the TIPS was complicated by post-procedural shock and hypoxemia. In the setting of progressive acute kidney injury and pancytopenia, the patient was transitioned to IV micafungin (150 mg daily) and IV voriconazole (400 mg twice daily for one day followed by 300 mg twice daily). Due to the combination of respiratory failure, active infection, and location of the TIPS that extended into the base of the right atrium, re-transplantation (and removal of the TIPS) was not offered due to exceedingly high surgical risk. She remained on antifungal therapy indefinitely and over the subsequent three months developed recurrent vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia. Newly identified thrombus along a peripherally inserted central catheter suggested the possibility of line associated septic thrombophlebitis as the source of her Enterococcus bacteremia. Bacteremia recrudesced despite line extraction, eventual resolution of her line associated clot, and an appropriate course of proactively dosed IV daptomycin (400-915 mg daily). Repeat TTE did not reveal signs of infective endocarditis and CT confirmed recurrent TIPS thrombosis as the likely source of her refractory Enterococcus faecium bacteremia that progressed to develop a daptomycin minimum inhibitory concentration > 256. Although the patient improved clinically and initially cleared her bacteremia with IV linezolid (600 mg daily), she developed severe thrombocytopenia and gastrointestinal bleeding that precluded further use of this agent. The patient elected to pursue hospice care and died shortly thereafter.

This case is a unique account of polymicrobial TIPS stent infection occurring five years after TIPS creation, the longest interval reported[4]. Shunt infection is most commonly reported during TIPS creation or revision, and infrequently with biliary-shunt fistulae that may form following TIPS creation[11]. Our patient presented with recurrent E. coli bacteremia of unclear origin and ongoing active colitis. While it is possible that bacterial translocation into the portal vein blood in the setting of active colitis could lead to E. coli bacteremia and seeding of the TIPS, it seems more likely that the colitis and occlusion of the TIPS occurred as a result of a low-flow state with seeding of the occlusive TIPS thrombus during ongoing E. coli bacteremia. Evidence that supports colitis likely being ischemic during the second episode of E. coli bacteremia include the colonic biopsy results obtained during lower endoscopy that corresponded to areas of active colitis noted on CT imaging which did not show any microorganisms based on limited histopathological analysis (no gram staining performed). Alternative common sources of E. coli bacteremia were investigated during her second episode of bacteremia, including urinary infection, biliary leak, cholangitis, and bacterial gastroenteritis, and work-up was non-revealing. Moreover, there was a very low suspicion for infective endocarditis given the respective organism involved and no history of IV drug use. This was confirmed on multiple TTEs which did not show any vegetation. In summary, the initial source of infection that may have seeded the TIPS was not clearly identified -- bacterial translocation due to confirmed, active colitis is a plausible explanation but an alternate source such as genitourinary or biliary are also possible given that records do not indicate a source of the initial E. coli bacteremia. It is important to note that during this patient’s first E. coli bacteremia episode diagnostic imaging was delayed. Imaging was pursued during her second episode of E. coli bacteremia as the patient complained of right upper quadrant pain and this revealed an occluded TIPS that raised suspicion for endotipsitis. This patient continued to suffer from recurrent polymicrobial bacteremia and fungemia after multiple TIPS revisions likely from a chronically infected TIPS. The patient likely had incomplete stent endothelization given the use of tacrolimus, which increased her risk of stent colonization[9,10].

Determining treatment duration and whether liver transplantation should be considered in the clinical scenario of endotipsitis are challenging decisions. Available clinical care guidance derives from case reports and case series, hence underscoring the importance of reporting new cases. To date there are 59 cases[2,4,12-14] of TIPS stent infection with nine being polymicrobial (Tables 1 and 2)[15-19]. Initial treatment courses range from 2 to 6 wk of antimicrobial therapy, followed by long-term oral therapy and orthotopic liver transplantation when medical therapy fails (Table 2). Analysis of polymicrobial cases to date showed that infections resolved with liver transplantation (Table 2). If patients did not undergo transplantation they remained indefinitely on antifungal therapy. While TIPS thrombectomy and revision were not commonly undertaken, there should be consideration of early thrombectomy, as drug penetration and source control may be insufficient with only antimicrobial therapy. For instance, inadequate drug penetration has been noted with amphotericin for Candida infective endocarditis[7]. Hence, surgical intervention is recommended for left sided infective endocarditis involving fungal organisms, as well as for S. aureus, or other highly resistant organisms[15]. Considering the high mortality rate of fungal TIPS infections[14,20-24], approximately 60% (Table 1), it is unclear whether antifungal prophylaxis should be considered prior to a TIPS revision. Justification for this step is lacking due to paucity of prospective studies (not surprising given the rarity of this infection) and the absence of guidelines to identify high-risk patients.

| Microbial agent | Reported cases | Mortality rate, % |

| Enterococcus (faecalis, faecium) | 14 | 21 |

| Staphylococcus (aureus, epidermidis) | 9 | 44 |

| Escherichia coli | 7 | 43 |

| Candida (glabrata, albicans) | 7 | 57 |

| Lactobacillus (rhamnosus, acidophilus) | 3 | 67 |

| Streptococcus (sanguis, bovis) | 2 | 0 |

| Gemella morbillorum | 2 | 0 |

| Klebsiella (pneumonia, oxytoca) | 3 | 33 |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 | 0 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 | 0 |

| Salmonella typhi | 1 | 0 |

| polymicrobial infection | 9 | 50 |

| total | 59 | 39 |

| Case and microbial agent | Treatment course | Outcome | Ref. |

| Case 1: Gram-positive and negative bacteria, and fungus | Antibiotic × 2 wk->antifungal × 2 ws->antibiotics->liver transplant | Resolved | [2] |

| Case 2: Gram-negative bacteria | antibiotics × 6 wk->antibiotics -> liver transplant | Resolved | [4] |

| Case 3: Gram-negative bacteria | antibiotic × 4 wk | Resolved | [20] |

| Case 4: Gram-negative bacteria and fungus | antibiotics and antifungal × 6 wk-> antifungal indefinitely | Resolved | [20] |

| Case 5: Gram-positive and negative bacteria | antibiotics->TIPS revision | Death | [21] |

| Case 6: Gram-positive and negative bacteria, and fungi | antibiotics->antibiotics, antifungal and TIPS revision-> antibiotic->antibiotics and TIPS revision->oral antibiotics indefinitely | Unknown | [22] |

| Case 7: Gram-positive and negative bacteria, and fungus | antibiotics and antifungals->liver transplant | Resolved | [23] |

| Case 8: Gram-positive and negative bacteria | antimicrobials × 4 wk ->liver transplantation | Resolved | [24] |

| Case 9: Gram-positive and negative bacteria, and fungi | antibiotics × 10 d-> TIPS thrombectomy & revision, and antibiotics × 6 wk-> TIPS thrombectomy and revision, and antibiotics and antifungals for 6 wk->balloon sweep of TIPS, antifungals indefinitely with antibiotics as tolerated | Death | Current case |

In summary, we present a case of recurrent E. coli bacteremia due to a late TIPS infection and occlusion that later evolved to a polymicrobial, multidrug-resistant TIPS infection. The patient initially cleared her infection with antimicrobial therapy and TIPS thrombectomy. Unfortunately, the patient later developed recurrent polymicrobial bacteremia and fungemia from a chronically infected TIPS.

TIPS infection is a rare event that most commonly occurs following TIPS creation and revision, though as illustrated in this case report it may occur many years following TIPS creation. Clinicians should be aware of this clinical complication early in the course so a TIPS thrombectomy can be performed for source control and to improve antibiotic penetration of the TIPS. Moreover, literature review shows that the highest mortality rates with endotipsitis are with Candida and polymicrobial infections. Given the refractory nature of these infections, liver transplantation should be considered to provide definitive treatment when feasible. Lastly, the rarity of a TIPS infection limits the development of research studies, and current understanding of this entity relies mainly on case reports and case series, hence highlighting the need to continue to report new cases.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American College of Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Fernandes SA, Brazil; Tripathi D, United Kingdom S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The Role of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) in the Management of Portal Hypertension: update 2009. Hepatology. 2010;51:306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Darrow AW, Gaba RC, Lokken RP. Transhepatic Revision of Occluded Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Complicated by Endotipsitis. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35:492-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Garcia-Zamalloa A, Gomez JT, Egusquiza AC. New Case of Endotipsitis: Urgent Need for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Eurasian J Med. 2017;49:214-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Navaratnam AM, Grant M, Banach DB. Endotipsitis: A case report with a literature review on an emerging prosthetic related infection. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:710-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chehab MA, Thakor AS, Tulin-Silver S, Connolly BL, Cahill AM, Ward TJ, Padia SA, Kohi MP, Midia M, Chaudry G, Gemmete JJ, Mitchell JW, Brody L, Crowley JJ, Heran MKS, Weinstein JL, Nikolic B, Dariushnia SR, Tam AL, Venkatesan AM. Adult and Pediatric Antibiotic Prophylaxis during Vascular and IR Procedures: A Society of Interventional Radiology Practice Parameter Update Endorsed by the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and the Canadian Association for Interventional Radiology. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29:1483-1501.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, Travis S, Armstrong MJ, Tsochatzis EA, Rowe IA, Roslund N, Ireland H, Lomax M, Leithead JA, Mehrzad H, Aspinall RJ, McDonagh J, Patch D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Gut. 2020;69:1173-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 43.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Steinbach WJ, Perfect JR, Cabell CH, Fowler VG, Corey GR, Li JS, Zaas AK, Benjamin DK Jr. A meta-analysis of medical vs surgical therapy for Candida endocarditis. J Infect. 2005;51:230-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Venditti M. Clinical aspects of invasive candidiasis: endocarditis and other localized infections. Drugs. 2009;69 Suppl 1:39-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Matter CM, Rozenberg I, Jaschko A, Greutert H, Kurz DJ, Wnendt S, Kuttler B, Joch H, Grünenfelder J, Zünd G, Tanner FC, Lüscher TF. Effects of tacrolimus or sirolimus on proliferation of vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;48:286-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Prado AP, Pérez-Martínez C, Cuellas-Ramón C, Gonzalo-Orden JM, Regueiro-Purriños M, Martínez B, García-Iglesias MJ, Ajenjo JM, Altónaga JR, Diego-Nieto A, de Miguel A, Fernández-Vázquez F. Time course of reendothelialization of stents in a normal coronary swine model: characterization and quantification. Vet Pathol. 2011;48:1109-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim E, Lee SW, Kim WH, Bae SH, Han NI, Oh JS, Chun HJ, Lee HG. Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Occlusion Complicated with Biliary Fistula Successfully Treated with a Stent Graft: A Case Report. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13:e28993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Colston JM, Scarborough M, Collier J, Bowler IC. High-dose daptomycin monotherapy cures Staphylococcus epidermidis 'endotipsitis' after failure of conventional therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | DeSimone JA, Beavis KG, Eschelman DJ, Henning KJ. Sustained bacteremia associated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:384-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anstead GM, Martinez M, Graybill JR. Control of a Candida glabrata prosthetic endovascular infection with posaconazole. Med Mycol. 2006;44:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sanyal AJ, Reddy KR. Vegetative infection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:110-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Armstrong PK, MacLeod C. Infection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt devices: three cases and a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:407-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Suhocki PV, Smith AD, Tendler DA, Sexton DJ. Treatment of TIPS/biliary fistula-related endotipsitis with a covered stent. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:937-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jawaid Q, Saeed ZA, Di Bisceglie AM, Brunt EM, Ramrakhiani S, Varma CR, Solomon H. Biliary-venous fistula complicating transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt presenting with recurrent bacteremia, jaundice, anemia and fever. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1604-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Willner IR, El-Sakr R, Werkman RF, Taylor WZ, Riely CA. A fistula from the portal vein to the bile duct: an unusual complication of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1952-1955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | AATS Surgical Treatment of Infective Endocarditis Consensus Guidelines Writing Committee Chairs; Pettersson GB, Coselli JS; Writing Committee, Pettersson GB, Coselli JS, Hussain ST, Griffin B, Blackstone EH, Gordon SM, LeMaire SA, Woc-Colburn LE. 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: Surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: Executive summary. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:1241-1258.e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McCarty TR, Sack J, Syed B, Kim R, Njei B. Fungal endotipsitis: A case report and literature review. J Dig Dis. 2017;18:237-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Darwin P, Mergner W, Thuluvath P. Torulopsis glabrata fungemia as a complication of a clotted transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:89-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schiano TD, Atillasoy E, Fiel MI, Wolf DC, Jaffe D, Cooper JM, Jonas ME, Bodenheimer HC Jr, Min AD. Fatal fungemia resulting from an infected transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stent. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:709-710. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Brickey TW, Trotter JF, Johnson SP. Torulopsis glabrata fungemia from infected transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stent. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:751-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |