Published online Jan 27, 2022. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v14.i1.224

Peer-review started: March 26, 2021

First decision: November 11, 2021

Revised: December 2, 2021

Accepted: December 25, 2021

Article in press: December 25, 2021

Published online: January 27, 2022

Processing time: 300 Days and 19.2 Hours

Liver surgery has traditionally been characterized by the complexity of its procedures and potentially high rates of morbidity and mortality in inexperienced hands. The robotic approach has gradually been introduced in liver surgery and has increased notably in recent years. However, few centers currently perform robotic liver surgery and experiences in robot-assisted surgical procedures continue to be limited compared to the laparoscopic approach.

To analyze the outcomes and feasibility of an initial robotic liver program implemented in an experienced laparoscopic hepatobiliary center.

A total of forty consecutive patients underwent robotic liver resection (da Vinci Xi, intuitive.com, United States) between June 2019 and January 2021. Patients were prospectively followed and retrospectively reviewed. Clinicopathological characteristics and perioperative and short-term outcomes were analyzed. Data are expressed as mean and standard deviation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

The mean age of patients was 59.55 years, of which 18 (45%) were female. The mean body mass index was 29.41 kg/m². Nine patients (22.5%) were cirrhotic. Patients were divided by type of resection as follows: Ten segmentectomies, three wedge resections, ten left lateral sectionectomies, six bisegmentectomies (two V-VI bisegmentectomies and four IVb-V bisegmentectomies), two right anterior sectionectomies, five left hepatectomies and two right hepatectomies. Malignant lesions occurred in twenty-nine (72.5%) of the patients. The mean operative time was 258.11 min and two patients were transfused intraoperatively (5%). Inflow occlusion was used in thirty cases (75%) and the mean total clamping time was 32.62 min. There was a single conversion due to uncontrollable hemorrhage. Major postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo > IIIb) occurred in three patients (7.5%) and mortality in one (2.5%). No patient required readmission to the hospital. The mean hospital stay was 5.6 d.

Although robotic hepatectomy is a safe and feasible procedure with favorable short-term outcomes, it involves a demanding learning curve that requires a high level of training, skill and dexterity.

Core Tip: The number of liver procedures performed laparoscopically remains highly variable, ranging from 10% up to 80% in some centers, and complex hepatectomies are still confined to expert and experienced laparoscopic liver surgeons. The robotic approach is gradually being introduced in liver surgery and has increased notably in recent years, which could compensate for the inherent difficulties of the laparoscopic approach. In this study, we analyzed our single-center data of robotic liver resections using the da Vinci Xi System®.

- Citation: Durán M, Briceño J, Padial A, Anelli FM, Sánchez-Hidalgo JM, Ayllón MD, Calleja-Lozano R, García-Gaitan C. Short-term outcomes of robotic liver resection: An initial single-institution experience. World J Hepatol 2022; 14(1): 224-233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v14/i1/224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v14.i1.224

Liver surgery has traditionally been characterized by the complexity of its procedures and potentially high rates of morbidity and mortality in inexperienced hands. In recent years, laparoscopic liver surgery has notably increased due to the beneficial outcomes in terms of fewer complications and transfusions, less blood loss and shorter hospital stays compared to open surgery with similar oncologic outcomes[1,2].

The number of liver procedures performed laparoscopically remains highly variable, ranging from 10% up to 80% in some centers[3]. Complex hepatectomies such as major hepatectomies or in posterosuperior segments are still restricted to expert laparoscopic liver surgeons with considerable experience due to their inherent risk, which make them very technically demanding procedures[4-6]. The increase in laparoscopic liver resections (LLR) has been accompanied by the development of parenchymal transection equipment and improved optical systems to compensate for the limitations of this approach and to increase the safety of hepatic resections[7].

The robotic approach is gradually being introduced in liver surgery and could compensate for the inherent difficulties of the laparoscopic approach. However, only some centers have implemented robotic-assisted surgery and the experience continues to be limited compared to laparoscopy[8]. In this study, we report an initial experience with our first forty robotic liver resections (RLRs) using the da Vinci Xi SystemÒ (Intuitive Surgical, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, United States). The aim of this study was to analyze the outcomes and feasibility of an initial robotic liver program implemented in an experienced laparoscopic hepatobiliary center.

Following Institutional Review Board approval, we performed a retrospective review on our prospective recorded single-institution data between June 2019 and January 2021, including sixty-three patients who underwent a hepatobiliopancreatic procedure as follows: Nineteen distal pancreatectomies, four bilioenteric reconstructions and forty Liver resections. Forty RLRs were performed by a single hepatic surgeon (Dr. Briceño J) and included in the study. The indication of robotic surgery was established when the patient was considered a suitable candidate for minimally invasive surgical approach. All patients gave their informed consent prior to surgery.

Patient preoperative data included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American society of anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, comorbidities, previous abdominal surgery and presence of chronic liver disease.

Intraoperative parameters included operative time, blood transfusion, use of inflow occlusion and duration and conversion rate. Operative time was defined as the time from the first incision to closure. Intraoperative complications were defined as an event requiring major deviation from the planned procedure.

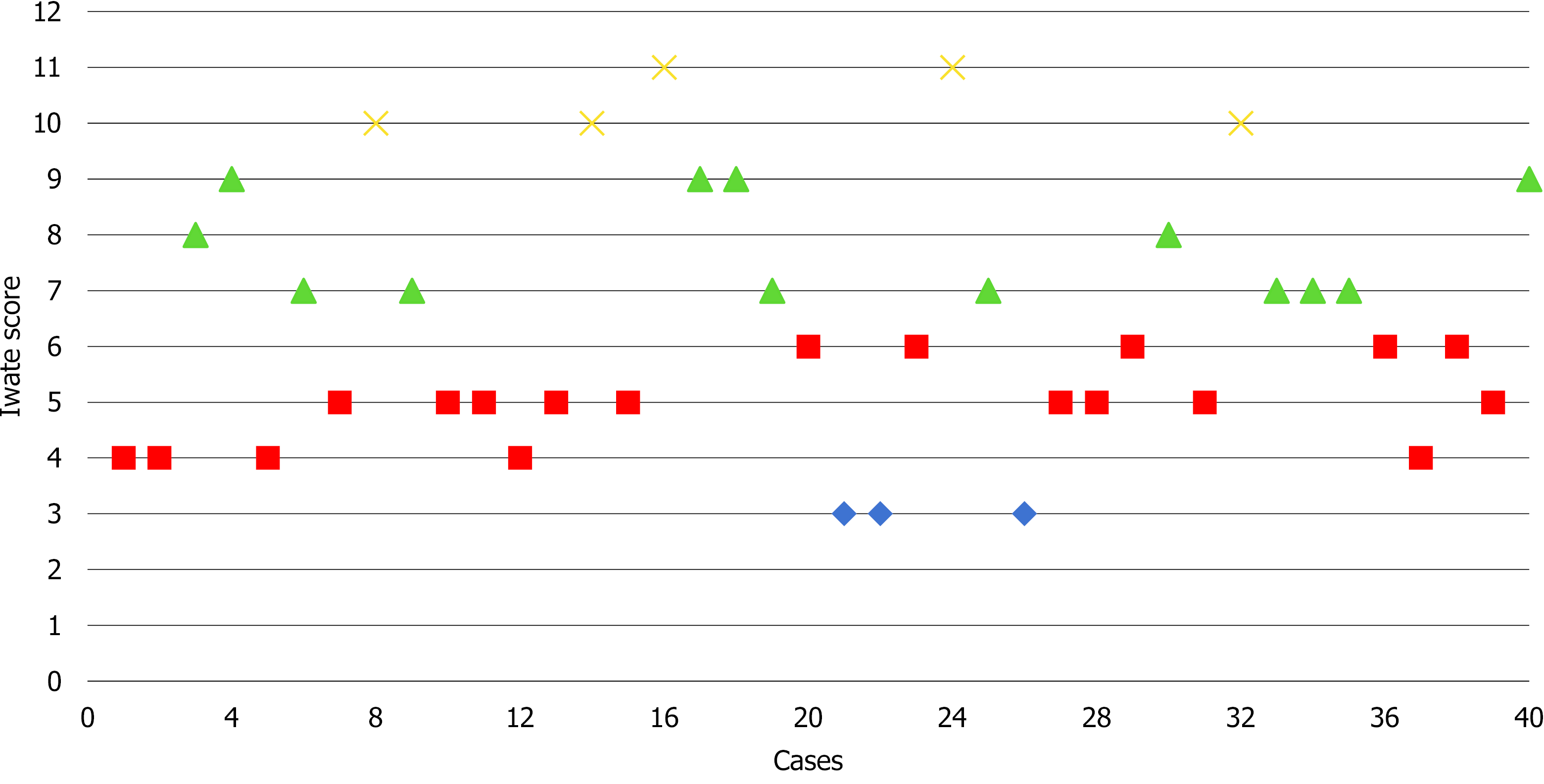

The anatomical location of the lesions and surgical resection were defined according to the Brisbane terminology[9]. The difficulty of the liver resections was graded according to the IWATE scoring system as revised in the Morioka consensus conference whereby a score of 0-3 is graded as low difficulty, 4-6 as intermediate difficulty, 7-9 as advanced difficulty and 10-12 as expert difficulty[10].

Postoperative variables were postoperative complications, length of stay, readmission within 30 d and mortality. Postoperative complications were recorded using the Clavien–Dindo classification up to 90 d after surgery[11]. Complications were considered major when Clavien-Dindo > III.

The characteristics, diagnosis, number and size of the lesions were determined by pathological reports. Resection margins were defined as R0 resection when tumor distance from the margin was greater than 1 mm, as R1 resection when tumor distance from the margin was less than 1 mm and as R2 resection upon presence of macroscopic tumor at the margin.

Statistics demographic data and clinical outcomes were analyzed. The descriptive analysis included mean and standard deviation in continuous variables, while categorical and ordinal variables were reported as counts with proportions. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States).

After anesthesia, patients are placed in the French position and in the reverse Trendelenburg position (15°) with a slight left tilt (5°). The assistant is located between the patient’s legs and the robot is located at the left shoulder. The trocars are placed according to the following surgical requirements: The transection plane, the segments involved and the position of the endostapler. For a right hepatic lobe procedure, a 12 mm camera port is introduced in the right paraumbilical area and the main working ports (first and third robotic arm ports on the left and right, respectively) are placed in the left and right upper quadrant area. The fourth robotic trocar is placed near the left anterior axillary line. For a left hepatic lobe procedure or a left hepatectomy, trocar placement is similar to that described previously; however, the camera port is placed at the umbilicus to visualize the target anatomy. Once the robotic trocars are placed, the da Vinci Xi robotic system (Intuitive.com, United States) is docked. An AirSeal port (SurgiQuest Inc., Milford, CT, United States) is used for bedside assistance. An intracorporeal pringle maneuver using Huang’s loop is applied and used when deemed appropriate (Figure 1).

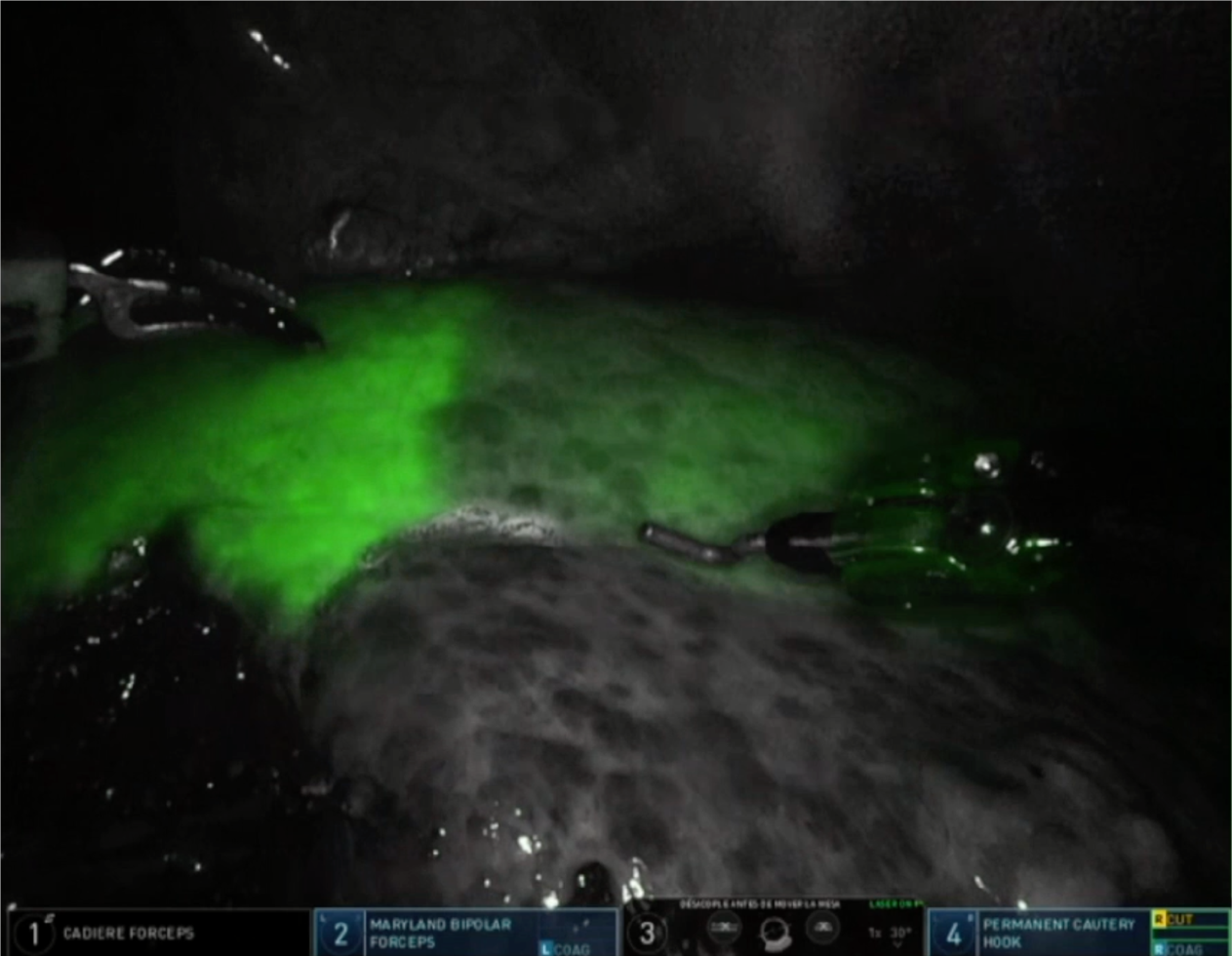

A robotic vessel sealer and bipolar cautery are the main instruments employed for parenchymal transection using the crush-clamp technique. An intraoperative robotic ultrasound device is employed to confirm the location of the tumor and to check the surgical transection line. For anatomic liver resection, indocyanine green may be injected intravenously to visualize hepatic perfusion and the demarcation line by negative staining (Figure 2). Finally, the specimen is removed from the abdominal cavity by means of an extraction bag.

Forty patients underwent RLR for benign or malignant tumors. Overall, the mean age was 59.6 (± 11.8), of which 18 (45%) were female. The mean BMI was 29.4 (± 4.7). Seventeen patients (42.5%) underwent a previous surgery (laparoscopic or “open”). A total of 72.5% (n = 29) of all lesions were malignant (primary lesions n = 23, metastatic lesions n = 6). Five lesions (12.5%) were located in the postero-superior segments (IVa, VII and VIII). The patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Sex (female) | 18 (45) |

| Age (yr) | 59.6 ± 11.8 |

| BMI | 29.4 ± 4.7 |

| ASA class | |

| ASA I | 3 (7.5) |

| ASA II | 13 (32.5) |

| ASA III | 24 (60) |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 17 (42.5) |

| Chronic liver disease | 12 (30) |

| History of type 2 diabetes | 14 (35) |

| History of hypertension | 22 (55) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 7 (17.5) |

| Chronic cardiac disease | 7 (17.5) |

| Chronic renal disease | 2 (5) |

| Viral infection | |

| HCV | 5 (17.5) |

| HBV | 1 (2.5) |

| Benign/malignant | 11 (27.5)/29 (72.5) |

The type of liver resection, simultaneous combined procedures and outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Nine patients (22.5%) were cirrhotic and another 22.5% had moderate to severe hepatic steatosis. Seven (17.5%) major hepatectomies were performed, of which five were left hepatectomies and two right hepatectomies. Additionally, thirty-three (82.5%) minor hepatectomies were performed: Ten segmentectomies, three wedge resections, ten left lateral sectionectomies, six bisegmentectomies (two V-VI bisegmentectomies, four IVb-V bisegmentectomies), two right posterior sectionectomies and two right anterior sectionectomies. Two patients underwent a simultaneous resection of the primary tumor and the metastatic liver lesions. Of these, one underwent a distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy and anatomic right hepatectomy and the other underwent a low anterior resection with hepatic wedge resection. Only one patient was converted to the “open” approach due to hemorrhage. Based on the IWATE criteria, 3/40 operations were categorized as low difficulty, 19/40 as intermediate, 13/40 as advanced and 5/40 as expert (see Figure 3).

| Type of liver resection, n (%) | Combined procedures | Cirrhosis | Conversion | Postoperative complications | |

| Wedge resection | 3 (7.5) | LAR (1), CH (2) | |||

| Segmentectomy | 10 (25) | CH (3) | 4 | 1 (Bleeding) | Ascites (1), colon ischemia (1) |

| Left lateral sectionectomy | 10 (25) | CH (1) | 4 | AKI (1), POT (1) | |

| Bisegmentectomy V-VI | 2 (5) | CH (1) | |||

| Bisegmentectomy IVb-V | 4 (10) | CH (3) | |||

| Right posterior sectionectomy | 2 (5) | CH (1) | |||

| Right anterior sectionectomy | 2 (5) | CH (2) | Ileus (1) | ||

| Left hepatectomy | 5 (12.5) | RFA (1), CH (4) | Bile leak (1) | ||

| Right hepatectomy | 2 (5) | PS (1), CH (1) | 1 | PHLF, ascites, LGIB and AKI (1), Bile leak (1) | |

Eight patients developed complications and are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Major complications (Clavien-Dindo > III) occurred in three patients (7.5%). Postoperative complications included ascites (1), ileus (1), acute renal injury (1) and bile leak (2), for which one patient required endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. One cirrhotic patient who underwent a right hepatectomy developed post-hepatectomy liver failure, ascites, acute kidney injury and lower gastrointestinal bleeding with no findings at colonoscopy.

| Operative duration (min) | 247.6 ± 119.2 |

| Inflow occlusion | 30 (75%) |

| Total clamping time (min) | 32.6 ± 26.6 |

| Intraoperative vasopressors use | 14 (35%) |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | 2 (5%) |

| Postoperative complications | 8 (20%) |

| Clavien–dindo classification | |

| Grade I | 1 |

| Grade II | 4 |

| Grade IIIa | 2 |

| Grade IIIb | |

| Grade IV | |

| Grade V | 1 |

| Conversion | 1 (2.5%) |

| Mortality | 1 (2.5%) |

| Length of stay (d) | 5.6 ± 6.1 |

| 30-d readmission |

The mean operative duration was 247.6 (± 119.2) min. Inflow occlusion was used in 30 cases (75%) and mean total clamping time was 32.6 (± 26.6) min. Two patients were transfused intraoperatively (5%) and vasopressors were used intraoperatively in fourteen cases (35%). The overall mean length of stay was 5.6 (± 6.1) d, while for minor hepatectomies was 4.4 (± 3.6) d and for major hepatectomies was 14 (± 12.6) d.

The pathologic findings are summarized in Table 4. The mean number of lesions was 1.2 (± 0.7), the mean size was 60.6 (± 40.5) and R0 resection was performed in twenty-seven (93%) of malignant cases. Of the forty operations, the most common diagnoses were as follows: Sixteen (40%) hepatocellular carcinoma, six (15%) intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, five (12.5%) colorectal metastases and four (10%) giant hemangiomas.

| Malignant | n (%) |

| Primary | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 16 (40) |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 6 (15) |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 1 (2.5) |

| Metastatic | |

| Colorectal metastases | 5 (12.5) |

| Non-colorectal metastases | 1 (2.5) |

| Benign | |

| Adenoma | 1 (2.5) |

| Giant hemangioma | 4 (10) |

| Giant focal nodular hyperplasia | 3 (7.5) |

| Hydatid cyst | 2 (5) |

| Simple cyst | 1 (2.5) |

| Number of lesions | 1.2 ± 0.7 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 60.6 ± 40.5 |

| Surgical margin | |

| R0 | 27 (93) |

| R1 | 2 (7) |

The minimally invasive approach in liver surgery has revolutionized the management of patients with liver tumors due to its demonstrated superiority over open surgery in terms of hospital stay, morbidity and blood loss[12,13].

Despite the exponential increase in laparoscopic liver surgery in recent years, the development of this surgical procedure has been a real challenge and even today the majority of hepatectomies performed by laparoscopy are the least complex, while major LLRs are still performed in few expert centers. A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated similar outcomes between laparoscopic and robotic major hepatectomies[14]. Most procedures were performed in specialized centers by liver surgeons with great previous expertise on minimally invasive surgery, demonstrating a severe complication rate of 6.7% and 3.6%, respectively, and almost zero risk of death.

Certain aspects associated with the laparoscopic approach, such as unstable cameras, rigid instruments with reduced degrees of freedom, human hand tremors, poor surgeon ergonomics and the difficulty of suturing in hard-to-reach locations constitute a serious limitation for performing complex hepatectomies[15]. Robotic systems have compensated for the limitations inherent in the laparoscopic approach as they use stable, 3D high-definition cameras that eliminate hand tremors and provide 7 degrees of freedom, thus increasing manual dexterity and facilitating liver resections. Moreover, it has been shown that robotic platforms reduce physical workload and are less strenuous for surgeons, so they may reduce musculoskeletal strain and disorders[16,17].

In this study, we present our initial experience in robotic liver surgery. Comparing our experience with those reported by other specialized centers, some have performed a greater number of RLRs, but the study interval is greater[18-25]. In our series, forty RLRs were performed in 18 mo and included major hepatectomies and cirrhotic patients. Most of the patients were overweight, middle-aged men, the majority of whom were ASA class III and had several comorbidities. Resections were mainly performed for malignant lesions, with hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal metastases being the most common diagnoses. Two patients underwent a simultaneous resection of the primary tumor (distal pancreatectomy and low anterior resection) and liver metastasis.

Resections for liver metastases were only performed in the absence of peritoneal carcinomatosis or unresectable extrahepatic disease. All patients with malignant disease except two had negative margins after the resection. Of the total number of patients, eleven (27.5%) had benign indications for liver resections. Benign lesions were resected because of severe symptoms caused by tumor size, radiological features of malignancy or diagnostic uncertainty despite preoperative biopsies and underwent anatomic resection.

Regarding the type of resection performed, left lateral sectionectomy (25%) and segmentectomy (25%) were the most frequently performed resections. To study the complexity of the RLRs performed, we employed the IWATE score. The effectiveness of the IWATE score as an indicator of operative difficulty in LLR has been demonstrated and several groups have previously considered that its usefulness in laparoscopic liver surgery could be extrapolated to the robotic approach[26,27]. In this study, 45% of the procedures were classified as advanced and expert. These percentages are similar to those of Labadie et al[26] (43%) and lower than the data reported by Sucandy et al[27] (68.6%). As can be seen in Figure 3 showing the cases performed to date and their degree of difficulty, the 45% of RLRs performed were classified as advanced and expert. In our experience, this is due to two reasons: The advantages of the robotic approach for surgeons and the extensive background of our group in laparoscopic liver surgery, which has provided the surgeons an understanding of the specific features and difficulties of this minimally invasive approach. In the coming years, the IWATE score will likely have to be adapted to robotic-assisted liver surgery, as this approach allows accessing posterior superior segments but shows difficulties associated with the resection of various lesions in different quadrants. RLR may favor the operative feasibility of highly difficult resections reducing the conversion rate and increasing safety. However, it does not translate directly into a postoperative course more favorable than pure laparoscopy, as we are still comparing two minimally invasive approaches[28].

Although the overall complication rate was 20%, major complications (Clavien–Dindo > III) occurred in three patients (7.5%). The postoperative complication rate in our study (20%) is similar to that published in a recent metanalysis by Guan et al[29] (19.2%), which included 435 RLRs. Reported conversion rates range from 0%-6%[18,19,21,22,30]. The only conversion to the “open” approach in our series (2.5%) occurred in a cirrhotic patient due to hemorrhage from a right inferior hepatic vein during a segment VI resection which required a cava vein venorrhaphy. The only death in our series occurred in a patient with a previous history of autoimmune vasculopathy who underwent a segment VI segmentectomy. The patient developed pancolonic ischemia at postoperative day 7 requiring intervention and died 18 d after being admitted to the Intensive care unit due to massive intestinal ischemia.

The main limitations to the present study are its single-arm design, the relatively small sample size and the retrospective nature of the analysis despite prospective recording. The lack of financial costs and quality of life analysis prevent a deeper investigation.

The results reported in this initial case series reflect perioperative outcomes similar to those published previously which support the safety and feasibility of this approach in liver surgery. Previous experience in minimally invasive liver surgery is necessary to overcome the initial difficulties of the robotic approach and perform complex liver procedures in a short period of time.

Future work is required to clarify the role of the robotic approach in complex hepatectomies.

The implementation of a liver robotic surgery program is safe and feasible with favorable short-term outcomes.

Forty consecutive patients underwent robotic liver resection between June 2019 and January 2021. Liver resection included: Ten segmentectomies, three wedge resections, ten left lateral sectionectomies, six bisegmentectomies (two V-VI bisegmentectomies and four IVb-V bisegmentectomies), two right anterior sectionectomies, five left hepatectomies and two right hepatectomies.

In this study patients were prospectively followed and retrospectively reviewed. The study was conducted according to STROBE statements.

The authors aimed to analyze the outcomes and feasibility of an initial robotic liver surgery program implemented in an experienced laparoscopic hepatobiliary center.

A robotic liver surgery program has been implemented in our center which has significant previous experience in minimally invasive surgery.

In recent years, minimal invasive liver surgery has notably increased due to its perioperative and postoperative favorable outcomes.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li HL, Ziogas IA S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang JL

| 1. | Jin B, Chen MT, Fei YT, Du SD, Mao YL. Safety and efficacy for laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy: A meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:A26-A34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xing L, Guo HB, Kan JL, Liu SG, Lv HT, Liu JH, Bian W. Clinical outcome of open surgery versus laparoscopic surgery for cirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;32:239-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Viganò L, Cimino M, Aldrighetti L, Ferrero A, Cillo U, Guglielmi A, Ettorre GM, Giuliante F, Dalla Valle R, Mazzaferro V, Jovine E, De Carlis L, Calise F, Torzilli G; Italian Group of Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery (I Go MILS). Multicentre evaluation of case volume in minimally invasive hepatectomy. Br J Surg. 2020;107:443-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Choi GH, Chong JU, Han DH, Choi JS, Lee WJ. Robotic hepatectomy: the Korean experience and perspective. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2017;6:230-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tzanis D, Shivathirthan N, Laurent A, Abu Hilal M, Soubrane O, Kazaryan AM, Ettore GM, Van Dam RM, Lainas P, Tranchart H, Edwin B, Belli G, Campos RR, Pearce N, Gayet B, Dagher I. European experience of laparoscopic major hepatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:120-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kasai M, Cipriani F, Gayet B, Aldrighetti L, Ratti F, Sarmiento JM, Scatton O, Kim KH, Dagher I, Topal B, Primrose J, Nomi T, Fuks D, Abu Hilal M. Laparoscopic versus open major hepatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Surgery. 2018;163:985-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Velayutham V, Fuks D, Nomi T, Kawaguchi Y, Gayet B. 3D visualization reduces operating time when compared to high-definition 2D in laparoscopic liver resection: a case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:147-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ciria R, Berardi G, Alconchel F, Briceño J, Choi GH, Wu YM, Sugioka A, Troisi RI, Salloum C, Soubrane O, Pratschke J, Martinie J, Tsung A, Araujo R, Sucandy I, Tang CN, Wakabayashi G. The impact of robotics in liver surgery: A worldwide systematic review and short-term outcomes meta-analysis on 2,728 cases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Strasberg SM. Nomenclature of hepatic anatomy and resections: a review of the Brisbane 2000 system. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:351-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wakabayashi G. What has changed after the Morioka consensus conference 2014 on laparoscopic liver resection? Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2016;5:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24843] [Article Influence: 1183.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Okuno M, Goumard C, Mizuno T, Omichi K, Tzeng CD, Chun YS, Aloia TA, Fleming JB, Lee JE, Vauthey JN, Conrad C. Operative and short-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for colorectal liver metastases located in the posterosuperior liver: a propensity score matching analysis. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1776-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Meng XF, Xu YZ, Pan YW, Lu SC, Duan WD. Open versus laparoscopic hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:2396-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ziogas IA, Giannis D, Esagian SM, Economopoulos KP, Tohme S, Geller DA. Laparoscopic versus robotic major hepatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:524-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tsilimigras DI, Moris D, Vagios S, Merath K, Pawlik TM. Safety and oncologic outcomes of robotic liver resections: A systematic review. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:1517-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dalager T, Jensen PT, Eriksen JR, Jakobsen HL, Mogensen O, Søgaard K. Surgeons' posture and muscle strain during laparoscopic and robotic surgery. Br J Surg. 2020;107:756-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dalsgaard T, Jensen MD, Hartwell D, Mosgaard BJ, Jørgensen A, Jensen BR. Robotic Surgery Is Less Physically Demanding Than Laparoscopic Surgery: Paired Cross Sectional Study. Ann Surg. 2020;271:106-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sucandy I, Giovannetti A, Ross S, Rosemurgy A. Institutional First 100 Case Experience and Outcomes of Robotic Hepatectomy for Liver Tumors. Am Surg. 2020;86:200-207. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Quijano Y, Vicente E, Ielpo B, Duran H, Diaz E, Fabra I, Olivares S, Ferri V, Ortega I, Malavé L, Ferronetti A, Piccinni G, Caruso R. Robotic Liver Surgery: Early Experience From a Single Surgical Center. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fruscione M, Pickens R, Baker EH, Cochran A, Khan A, Ocuin L, Iannitti DA, Vrochides D, Martinie JB. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic major liver resection: analysis of outcomes from a single center. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:906-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choi GH, Choi SH, Kim SH, Hwang HK, Kang CM, Choi JS, Lee WJ. Robotic liver resection: technique and results of 30 consecutive procedures. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2247-2258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Valverde A, Abdallah S, Danoussou D, Goasguen N, Jouvin I, Oberlin O, Lupinacci RM. Transitioning From Open to Robotic Liver Resection. Results of 46 Consecutive Procedures Including a Majority of Major Hepatectomies. Surg Innov. 2021;28:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goh BKP, Lee LS, Lee SY, Chow PKH, Chan CY, Chiow AKH. Initial experience with robotic hepatectomy in Singapore: analysis of 48 resections in 43 consecutive patients. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ceccarelli G, Andolfi E, Fontani A, Calise F, Rocca A, Giuliani A. Robot-assisted liver surgery in a general surgery unit with a "Referral Centre Hub&Spoke Learning Program". Early outcomes after our first 70 consecutive patients. Minerva Chir. 2018;73:460-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee B, Choi Y, Cho JY, Yoon YS, Han HS. Initial experience with a robotic hepatectomy program at a high-volume laparoscopic center: single-center experience and surgical tips. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Labadie KP, Droullard DJ, Lois AW, Daniel SK, McNevin KE, Gonzalez JV, Seo YD, Sullivan KM, Bilodeau KS, Dickerson LK, Utria AF, Calhoun J, Pillarisetty VG, Sham JG, Yeung RS, Park JO. IWATE criteria are associated with perioperative outcomes in robotic hepatectomy: a retrospective review of 225 resections. Surg Endosc. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Luberice K, Sucandy I, Modasi A, Castro M, Krill E, Ross S, Rosemurgy A. Applying IWATE criteria to robotic hepatectomy: is there a "robotic effect"? HPB (Oxford). 2021;23:899-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cipriani F, Fiorentini G, Magistri P, Fontani A, Menonna F, Annecchiarico M, Lauterio A, De Carlis L, Coratti A, Boggi U, Ceccarelli G, Di Benedetto F, Aldrighetti L. Pure laparoscopic versus robotic liver resections: Multicentric propensity score-based analysis with stratification according to difficulty scores. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Guan R, Chen Y, Yang K, Ma D, Gong X, Shen B, Peng C. Clinical efficacy of robot-assisted versus laparoscopic liver resection: a meta analysis. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Morel P, Jung M, Cornateanu S, Buehler L, Majno P, Toso C, Buchs NC, Rubbia-Brandt L, Hagen ME. Robotic versus open liver resections: A case-matched comparison. Int J Med Robot. 2017;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |