Published online Mar 27, 2021. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i3.291

Peer-review started: November 16, 2020

First decision: January 18, 2021

Revised: January 20, 2021

Accepted: March 11, 2021

Article in press: March 11, 2021

Published online: March 27, 2021

Processing time: 123 Days and 3.2 Hours

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a dependent virus that relies on hepatitis B virus for its replication and transmission. Chronic hepatitis D is a severe form of viral hepatitis that can result in end stage liver disease. Currently, pegylated interferon alpha is the only approved therapy for chronic HDV infection and is associated with significant side effects. Liver transplantation (LT) is the only treatment option for patients with end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, or fulminant hepatitis due to coinfection with HDV. As LT for HDV and hepatitis B virus coinfection is uncommon in the United States, most data on the long-term impact of LT on HDV are from international centers. In this review, we discuss the indications and results of LT with treatment options in HDV patients.

Core Tip: Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a dependent virus and relies on hepatitis B virus (HBV) to synthesize the pathogenic genomes. Therefore, it can only survive as a coinfection with HBV or as a superinfection. Chronic HDV infection results in rapid liver damage and can result in end stage liver disease. Currently, pegylated interferon alpha is the only approved therapy for chronic HDV infection and is associated with significant side effects. Thus, liver transplant remains the only option for patients with end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma due to coinfection or superinfection with HDV and HBV, fulminant liver failure and those who cannot be treated with interferon-based therapies. Post transplantation reinfection with HDV/HBV is an undesirable outcome. Though, there is a consensus that hepatitis B immune globulin in combination with a potent nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have shown promising results. In addition, there is ongoing research for newer treatment drugs. This review article focuses on liver transplant in patients as a result of hepatitis D virus. We have discussed the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, indication of liver transplantation, treatment options and the outcomes. New therapy trials have been also discussed in the treatment section. We believe that this topic is an area of knowledge gap and this article will cover the basics.

- Citation: Muhammad H, Tehreem A, Hammami MB, Ting PS, Idilman R, Gurakar A. Hepatitis D virus and liver transplantation: Indications and outcomes. World J Hepatol 2021; 13(3): 291-299

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v13/i3/291.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v13.i3.291

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) was discovered in 1970s by Rizzetto et al[1]. It is formed by 1678 nucleotide single stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus which is circular in shape and contains two viral proteins that are p24 and p27[2,3]. There is a total of 8 genotypes of HDV in the world[4]. HDV is not able to make its own proteins and relies on hepatitis B virus (HBV) to synthesize the pathogenic genomes. Therefore, it can only survive as a coinfection with HBV or as a superinfection. Around 5% of HBV carriers worldwide have been exposed to HDV and the prevalence of HDV coinfection in United States is reported to be 12%[5,6]. Chronic HDV infection results in rapid liver damage compared to patients infected with HBV alone. In addition, incidence of cirrhosis is almost three times with HBV/HDV chronic coinfection and associated with increased rate of early decompensation leading to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[7]. As HDV uses host polymerase for replication, HBV polymerase inhibitors are not effective against it[8]. Therefore, the only widely accepted treatment is interferon at high doses which has a success rate of 25% to 30%, which is defined as virological response after one year of conventional or PEG-INFa treatment with most studies measuring virological response after 6 mo of treatment[9]. Thus, liver transplant (LT) remains the only option for patients with end-stage liver disease, HCC due to coinfection or superinfection with HDV and HBV, fulminant liver failure and those who cannot be treated with interferon-based therapies. In this review we discuss the indications of liver transplantation and its outcome in patients with HDV.

There are about 240 million people worldwide who have positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Amongst them 2% to 8% are co-infected with HDV resulting in approximately 20 to 40 million suffering from HDV[10,11]. However, recent studies have estimated the coinfection number to be higher as up to 72 million[12]. HDV is endemic in the Middle East, Mediterranean Area, Amazon Region, and African countries[13]. In Europe, HDV is mainly a problem in Eastern European immigrant populations and amongst intravenous drug users (IVDU)[14,15]. There are 8 different HDV genotypes and genotype 1 is the most common in North America[16]. Testing for HDV has not been widespread in the United States and the prevalence has been underestimated. There has been a 3.4% HDV seropositive rate reported in the veteran population positive with HBsAg[17]. In comparison, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (1999-2012) showed a significantly lower rate of HDV prevalence (0.02%) in the civilian population[18]. It increased to 0.11% in a repeat National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011-2016) study[19]. Both these studies are limited as they excluded homeless, incarcerated, and other high-risk individuals. However, a study done among patients with IVDU in Baltimore by Kucirka et al[20] reported 11% prevalence of HDV in 2005-2006. Similarly, Gish et al[21] conducted a study in California on chronic HBV patients reporting a coinfection rate of 8%. This variability warrants routine testing of HDV in HBV carriers with specific recommendations for screening, treatment and follow-up. This will aid risk stratification of patients and allow for early discovery of complications, which in turn may improve outcomes.

HDV is parenterally transmitted and has variable clinical manifestations. There are two major patterns of infection that are described in literature. Notably, coinfection of HBV with HDV and superinfection of HDV in chronic HBV-infected patients. HDV develops innate and adaptive immunity and there are specific markers such as HDV RNA, hepatitis D antigen and anti-HDV antibodies, such as IgM and IgG, which help to detect and differentiate the chronicity of the disease[22].

As HDV’s virulence is dependent on HBV, coinfection results from simultaneous acute HBV and HDV. It is usually transient and cannot be clinically distinguished from HBV infection[23]. HDV has incubation period of approximately 1 mo resulting in clinical symptoms of fatigue, loss of appetite and nausea. It is accompanied with a rise in liver enzymes, including serum alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase. Then comes the jaundice phase with increase in bilirubin levels. As it is usually self-limiting and most patients recover completely with only 2% leading to chronic infection[7,24].

Superinfection with HDV can also result in acute hepatitis which is more severe than seen with co-infection. This is because HBV has already set the ground for more aggressive disease progression. It can lead to acute liver failure with clinical symptoms starting as nausea and progressing to coagulopathy, encephalopathy and coma[25]. About 80% to 90% of patients progress to chronic hepatitis. Amongst them, some dated studies have reported up to 70% to 80% progress to cirrhosis within 5 to 10 years[26]. However, newer studies suggested a 4% annual progression to cirrhosis[27]. This variability might be due to the different genotypes of HDV. Although there is controversy in the literature over whether HDV has oncogenic properties, cirrhosis from HDV does increase the risk of HCC, which is the second most common cause of cancer deaths in men worldwide[28].

HBsAg is necessary before other markers for HDV are investigated to establish the diagnosis. One important distinguishing test is IgM anti-HBc, which is only present in acute HDV/HBV coinfection and not in acute HDV superinfection. Likewise, HDV RNA is a sensitive marker for acute infection and reaches a very high quantitative value in chronic patients. Similarly, the presence of anti-HDV IgM or high anti-HDV IgG titer can differentiate between current and past infections. Therefore, knowing these markers helps to differentiate the disease pattern (Table 1)[23].

| Coinfection | Superinfection | |

| HDV infection | Acute | Acute or chronic |

| IgM anti-HBc | Positive | Negative |

| Serum HDV RNA | Transient | Persistent and high |

| IgM anti-HDV | Transient | Persistent |

| IgG anti-HDV | Late appearance and low | Persistent and high |

The global disease burden of HBV/HDV coinfection is increasing with 10.6% of HBsAg carriers without high risk sexual behavior or IVDU are HDV[12]. HDV can lead to a more severe form of viral hepatitis than in HBV mono-infection[29]. Irrespective of whether being coinfected with HBV or as superinfection, HDV can cause fulminant hepatitis[30]. The clinical course of fulminant hepatitis D is 4 to 30 d and transplant free survival is as low as 20%[7,31].

Chronic HDV results in rapid liver fibrosis, earlier decompensation, higher risk of HCC development and annual mortality rate between 7% to 9%[32]. Mortality rates of greater than 50% at 15 years follow up have been reported in Taiwan[33]. Though direct oncogenic properties of HDV is not clearly described, higher rates of cirrhosis in HDV patients can lead to increased rates of HCC[34]. Rates of HCC are variable across the globe with studies showing anti-HDV antibodies ranging from 4% to 23% in HBsAg positive HCC patients[35,36]. Treatment option for HDV has limited success. Therefore, the only definitive therapy for patients with end-stage liver disease, HCC, or fulminant hepatitis due to HDV is liver transplant[13].

Currently there is no United States Food and Drug Administration approved treatment for HDV[37]. However, PEG-IFNa is commonly used and is also recommended by major liver societies such as American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and European Association for the Study of the Liver[38,39]. Pegylated form requires only weekly dosing and metanalysis has shown increased suppression (29%) of HDV RNA at 6 mo compared to standard IFN alpha (19%)[40]. In addition, PEG-IFNa is also associated with lower rates of side effects such as anorexia, nausea, weight loss, alopecia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia[41,42]. Although there is no definite treatment duration, negative HDV RNA at 24 wk is being considered a reference for virological response and treatment for 48 wk is recommended[38,43]. Pegylated IFN has been studied in combination with nucleosides. The Hep-Net/International Delta Hepatitis Intervention Trial randomized 90 patients to adefovir, peginterferon, or the combination arm. Approximately 25% achieved virological response at 24 wk in the peginterferon and combination group and none in the adefovir group[44]. Similarly, the HIDIT-2 trial (which replaced adefovir with tenofovir) yielded similar results to the trial[21] and did not show a response in the nucleoside alone[45]. Thus, combination of interferon with nucleosides or increasing the duration of treatment has shown no additional benefits.

In addition, newer experimental treatments are currently underway. One such example is the use of oral prenylation inhibitor lonafarnib (LNF). Prenylation inhibitors have been shown to abolish HDV-like particle production in vitro and in vivo[46]. LNF interferes with the HDV cycle and targets the virion assembly step in the hepatocyte cytoplasm, where the nascent HDV nucleoprotein complex is enveloped by HBsAg[47]. To explore this, the LOWR HDV-1 [Lonafarnib with and without Ritonavir (RTV) in HDV-1] phase two clinical trial was conducted by Yurdaydin et al[47] with the intention to study optimal LNF dosing while assessing tolerability and viral response when combined with P450 3A4 inhibitor RTV or PEG-IFNa. Results showed that LNF, whether as monotherapy or as combination with PEG-IFNa, led to HDV-RNA viral load decline in all patients. All treated patients in different treatment regimens reported GI adverse effects consisting of anorexia and weight loss. Higher dose of LNF, 300 mg peroral BID, was associated with increased adverse effects. RTV helped to lower LNF dose (100 mg per oral BID dosing) while still achieving better antiviral results. Similarly, LNF 100 mg BID with PEG-IFNa helped in more substantial and rapid HDV-RNA reduction, compared to PEG-IFNa alone[47]. Such trials have opened the door to further explore newer treatment options for HDV.

PEG-IFNa is only used amongst patients with compensated liver disease. For those who undergo LT, long-term survival depends on the prevention of allograft reinfection. LT for HDV is not common in United States and studies in literature are mostly from other countries[48,49]. Due to antivirals and with hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG), rates of HBV/HDV reinfection after LT has decreased[50]. Currently there is no specific prophylaxis for HDV. However, as its growth is dependent on HBV, the focus should be on preventing HBV infection.

Levels of HBV DNA (> 105 copies/mL) strongly predict HBV reinfection in HBsAg positive LT recipients[51]. As per AASLD recommendations, all HBsAg-positive recipients should receive prophylactic nucleoside/nucleotide analogs with or without HBIG post-LT. In addition, pretransplant hepatitis B e-antigen/HBV-DNA levels should not be taken into consideration and HBIG monotherapy should not be used. They further suggest that entecavir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and tenofovir alafenamide should be the preferred antivirals and continued indefinitely post-LT[38]. The use of HBIG depends on the recipient and virologic factors. In medically adherent HBV mono-infected recipients with undetectable or low-level viremia at the time of LT and no evidence of concurrent infection, no HBIG or a very short course (5 d) of HBIG post-LT combined with long-term antiviral therapy is highly effective in preventing HBV recurrence[38]. On the other hand, in HBV/HDV co-infected recipients, the combination of long-term HBIG and antiviral therapy may be the best approach in preventing HBV and HDV recurrence[38].

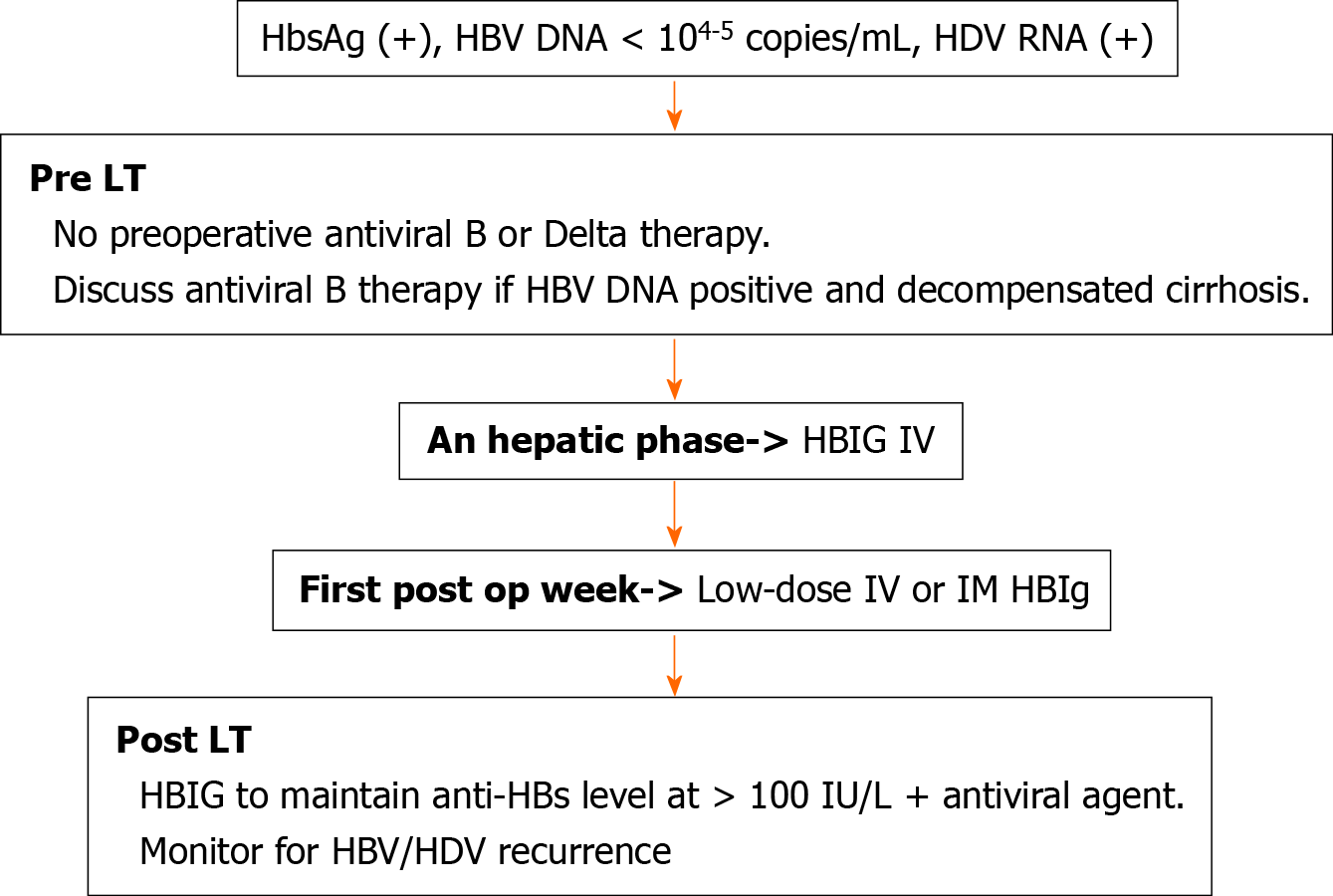

Data regarding the dosage of HBIG therapy varies across transplant centers. In previous studies HBIG has been given as either high (≥ 10000 IU/mL) or low (< 10000 IU/mL) dose for either a fixed duration (median of 6 mo) or indefinitely post-LT[50]. It is administered either intravenous or intramuscularly during an hepatic phase, followed by daily doses during the first week, with subsequent doses given monthly or by following anti-HBs titers based on the transplant center protocol[50]. A trough anti-HBs titer of at least 100 IU/L is thought to be protective and reinfection rate can be further reduced by maintaining anti-HBs titers consistently above 500 IU/L[52] (Figure 1)[48].

Long-term survival following LT for viral hepatitis depends on prevention of allograft reinfection[53]. This is a well-known concept for HBV as well as HCV and can be applied for HDV related LT as well. LT for HDV started in the late 1980s from Europe. One of the earliest reporting was from Rizzetto et al[54] from Italy, on 7 patients who underwent LT due to HDV cirrhosis. It resulted in reinfection rate of 70% with HDV and milder forms of hepatitis were reported in 40% of the cases. This encouraged others to believe that LT was a feasible option for ESLD from HDV. Ottobrelli et al[55] reported a larger series of 22 patients, which showed 80% reinfection rate and 73% survival rate at one year. Although the reinfection rate was high, the clinical course was mild, therefore giving hope to the patients that LT was the possible cure for HDV. At that time, it was unclear whether administration of HBIG will be beneficial in preventing reinfection. Therefore, a multicenter study was done in Europe and amongst 110 patients who underwent LT due to HDV cirrhosis, the three-year actuarial risk of HBV recurrence after transplantation was reported as 70% ± 14% in the group who received no HBIG and 17% ± 6% in patients who received HBIG for > 6 mo[56]. The actuarial three-year survival was reported as 83%. In that study, long-term administration of HBIG (RR: 2.22; 95% confidence interval: 1.13-4.33; P < 0.001) and HDV superinfection (RR: 6.25; 95% confidence interval: 3.13-12.42; P < 0.001) were reported as independent predictors of better survival[56]. With the passage of time and development of new antivirals which when used in combination with HBIG, post-LT HBV/HDV reinfection has significantly decreased. In a retrospective study Adil et al[57] reported HBV recurrence rate of 5.1% and no HDV recurrence among 255 patients, after a mean follow-up of 30 mo. Similarly, study by Idilman et al[58] endorsed this, showing that amongst 90 patients with delta co-infection-related cirrhosis who underwent LT, only one recipient (who received lamivudine and HBIG combination), had HBV recurrence upon follow up. Moreover, in an another study with 104 HDV patients, with a longer follow up of 82 mo, the survival and HBV recurrence rates were 97% and 13.4% respectively[59]. Thus, it was confirmed that it is very important for survival and viability of the graft that the patients remain HBsAg-negative after transplantation.

Interestingly, studies have shown that presence of HDV infection appears to provide a protective effect against HBV reinfection in LT patients, possibly via suppression of HBV replication resulting in longer survival rates[49]. Recently a study published on LT patients in Brazil showed significantly higher 4-year survival rate of 95% in HDV group (n = 29), compared to 75% in HBV group (n = 40)[60]. One of the largest series involving hepatic transplantation in patients with HDV (n = 76), identified 88% survival after 5 years[61]. This is likely because of low HBV recurrence rate in these series.

HDV leading to HCC has also been treated with LT. Romeo et al[27] performed a retrospective study where 29 of 299 patients diagnosed with HBV/HDV had liver transplant; amongst these 29 patients, 10 patients (34%) had HCC. After transplant, 5 patients died (3 with primary graft failure, 1 with tumor recurrence, and 1 with non-liver–cancer-related reasons). Similarly, a retrospective study was conducted in Turkey amongst 25 live donor LT recipients with chronic HBV/HDV, 11 of which had HCC. The cumulative 5-year survival was 74%. In the HCC group, 7 of 11 tumors matched the Milan criteria and 4 patients did not (in whom 2 patients had HCC recurrence after 2 years which was treated by ablation techniques)[32]. Thus, results from our review supports the AASLD guideline, that using HBIG in conjunction with oral antivirals post-transplantation, changes the natural history of the liver disease even among recipients with HCC.

HDV presents a severe health burden with liver transplantation as the only treatment for patients with End-stage Liver Disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, or fulminant hepatitis. Post transplantation reinfection with HDV/hepatitis B virus is an undesirable outcome as it affects survival. While transplant centers across the world have their own protocols, there is a consensus that hepatitis B immune globulin in combination with a potent nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have shown promising results. In the future, with the potential approval of the pipeline drugs for HDV treatment, their role in the post-transplant setting also needs to be explored. Currently, the data on liver transplant due to HDV is limited and more randomized controlled trials investigating the duration and frequency of hepatitis B immune globulin as well as the specific anti-HBs titer level are needed to optimize the pre- and post-transplant treatment plans.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jiménez Pérez M, Pyrsopoulos N S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Rizzetto M, Canese MG, Aricò S, Crivelli O, Trepo C, Bonino F, Verme G. Immunofluorescence detection of new antigen-antibody system (delta/anti-delta) associated to hepatitis B virus in liver and in serum of HBsAg carriers. Gut. 1977;18:997-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 683] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wang KS, Choo QL, Weiner AJ, Ou JH, Najarian RC, Thayer RM, Mullenbach GT, Denniston KJ, Gerin JL, Houghton M. Structure, sequence and expression of the hepatitis delta (delta) viral genome. Nature. 1986;323:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Chang FL, Chen PJ, Tu SJ, Wang CJ, Chen DS. The large form of hepatitis delta antigen is crucial for assembly of hepatitis delta virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8490-8494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wranke A, Wedemeyer H. Antiviral therapy of hepatitis delta virus infection - progress and challenges towards cure. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;20:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Te H, Doucette K. Viral hepatitis: Guidelines by the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Disease Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martins EB, Glenn J. Prevalence of Hepatitis Delta Virus (HDV) Infection in the United States: Results from an ICD-10 Review. AASLD abstracts. 2017;152:S1085. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Farci P, Niro GA. Clinical features of hepatitis D. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:228-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wranke A, Serrano BC, Heidrich B, Kirschner J, Bremer B, Lehmann P, Hardtke S, Deterding K, Port K, Westphal M, Manns MP, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H. Antiviral treatment and liver-related complications in hepatitis delta. Hepatology. 2017;65:414-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yurdaydin C. Treatment of chronic delta hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:237-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1806] [Cited by in RCA: 2000] [Article Influence: 200.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 11. | Hughes SA, Wedemeyer H, Harrison PM. Hepatitis delta virus. Lancet. 2011;378:73-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen HY, Shen DT, Ji DZ, Han PC, Zhang WM, Ma JF, Chen WS, Goyal H, Pan S, Xu HG. Prevalence and burden of hepatitis D virus infection in the global population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2019;68:512-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wedemeyer H, Manns MP. Epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of hepatitis D: update and challenges ahead. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wedemeyer H, Heidrich B, Manns MP. Hepatitis D virus infection--not a vanishing disease in Europe! Hepatology. 2007;45:1331-1332; author reply 1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cross TJ, Rizzi P, Horner M, Jolly A, Hussain MJ, Smith HM, Vergani D, Harrison PM. The increasing prevalence of hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection in South London. J Med Virol. 2008;80:277-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Radjef N, Gordien E, Ivaniushina V, Gault E, Anaïs P, Drugan T, Trinchet JC, Roulot D, Tamby M, Milinkovitch MC, Dény P. Molecular phylogenetic analyses indicate a wide and ancient radiation of African hepatitis delta virus, suggesting a deltavirus genus of at least seven major clades. J Virol. 2004;78:2537-2544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kushner T, Serper M, Kaplan DE. Delta hepatitis within the Veterans Affairs medical system in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Hepatol. 2015;63:586-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Njei B, Do A, Lim JK. Prevalence of hepatitis delta infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2012. Hepatology. 2016;64:681-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Patel EU, Thio CL, Boon D, Thomas DL, Tobian AAR. Prevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Virus Infections in the United States, 2011-2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:709-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kucirka LM, Farzadegan H, Feld JJ, Mehta SH, Winters M, Glenn JS, Kirk GD, Segev DL, Nelson KE, Marks M, Heller T, Golub ET. Prevalence, correlates, and viral dynamics of hepatitis delta among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:845-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Gish RG, Yi DH, Kane S, Clark M, Mangahas M, Baqai S, Winters MA, Proudfoot J, Glenn JS. Coinfection with hepatitis B and D: epidemiology, prevalence and disease in patients in Northern California. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1521-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abbas Z, Afzal R. Life cycle and pathogenesis of hepatitis D virus: A review. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:666-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Negro F. Hepatitis D virus coinfection and superinfection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a021550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Caredda F, Rossi E, d'Arminio Monforte A, Zampini L, Re T, Meroni B, Moroni M. Hepatitis B virus-associated coinfection and superinfection with delta agent: indistinguishable disease with different outcome. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:925-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Rajaram P, Subramanian R. Acute Liver Failure. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;39:513-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rizzetto M, Verme G, Recchia S, Bonino F, Farci P, Aricò S, Calzia R, Picciotto A, Colombo M, Popper H. Chronic hepatitis in carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen, with intrahepatic expression of the delta antigen. An active and progressive disease unresponsive to immunosuppressive treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:437-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Romeo R, Del Ninno E, Rumi M, Russo A, Sangiovanni A, de Franchis R, Ronchi G, Colombo M. A 28-year study of the course of hepatitis Delta infection: a risk factor for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1629-1638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25542] [Article Influence: 1824.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 29. | Fattovich G, Giustina G, Christensen E, Pantalena M, Zagni I, Realdi G, Schalm SW. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type B. The European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (Eurohep). Gut. 2000;46:420-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Botelho-Souza LF, Vasconcelos MPA, Dos Santos AO, Salcedo JMV, Vieira DS. Hepatitis delta: virological and clinical aspects. Virol J. 2017;14:177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sánchez-Tapias JM, Mas A, Costa J, Bruguera M, Mayor A, Ballesta AM, Compernolle C, Rodés J. Recombinant alpha 2c-interferon therapy in fulminant viral hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1987;5:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Öcal S, Korkmaz M, Harmancı Ö, Ensaroğlu F, Akdur A, Selçuk H, Moray G, Haberal M. Hepatitis B- and hepatitis D-virus-related liver transplant: single-center data. Exp Clin Transplant. 2015;13 Suppl 1:133-138. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Su CW, Huang YH, Huo TI, Shih HH, Sheen IJ, Chen SW, Lee PC, Lee SD, Wu JC. Genotypes and viremia of hepatitis B and D viruses are associated with outcomes of chronic hepatitis D patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1625-1635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Romeo R, Foglieni B, Casazza G, Spreafico M, Colombo M, Prati D. High serum levels of HDV RNA are predictors of cirrhosis and liver cancer in patients with chronic hepatitis delta. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Abbas Z, Abbas M, Abbas S, Shazi L. Hepatitis D and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:777-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Mahale P, Aka P, Chen X, Pfeiffer RM, Liu P, Groover S, Mendy M, Njie R, Goedert JJ, Kirk GD, Glenn JS, O'Brien TR. Hepatitis D virus infection, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in The Gambia. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:738-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Food and Drug Administration. Chronic Hepatitis D Virus Infection: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industry 2019 [cited March 7, 2021]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/chronic-hepatitis-d-virus-infection-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industry.. |

| 38. | Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr, Bzowej NH, Wong JB. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2290] [Cited by in RCA: 2845] [Article Influence: 406.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3802] [Article Influence: 475.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 40. | Alavian SM, Tabatabaei SV, Behnava B, Rizzetto M. Standard and pegylated interferon therapy of HDV infection: A systematic review and meta- analysis. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:967-974. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Abbas Z, Khan MA, Salih M, Jafri W. Interferon alpha for chronic hepatitis D. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011: CD006002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Castelnau C, Le Gal F, Ripault MP, Gordien E, Martinot-Peignoux M, Boyer N, Pham BN, Maylin S, Bedossa P, Dény P, Marcellin P, Gault E. Efficacy of peginterferon alpha-2b in chronic hepatitis delta: relevance of quantitative RT-PCR for follow-up. Hepatology. 2006;44:728-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mentha N, Clément S, Negro F, Alfaiate D. A review on hepatitis D: From virology to new therapies. J Adv Res. 2019;17:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wedemeyer H, Yurdaydìn C, Dalekos GN, Erhardt A, Çakaloğlu Y, Değertekin H, Gürel S, Zeuzem S, Zachou K, Bozkaya H, Koch A, Bock T, Dienes HP, Manns MP; HIDIT Study Group. Peginterferon plus adefovir vs either drug alone for hepatitis delta. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:322-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wedemeyer H, Yurdaydin C, Hardtke S, Caruntu FA, Curescu MG, Yalcin K, Akarca US, Gürel S, Zeuzem S, Erhardt A, Lüth S, Papatheodoridis GV, Keskin O, Port K, Radu M, Celen MK, Idilman R, Weber K, Stift J, Wittkop U, Heidrich B, Mederacke I, von der Leyen H, Dienes HP, Cornberg M, Koch A, Manns MP; HIDIT-II study team. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for hepatitis D (HIDIT-II): a randomised, placebo controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:275-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Glenn JS, Watson JA, Havel CM, White JM. Identification of a prenylation site in delta virus large antigen. Science. 1992;256:1331-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Yurdaydin C, Keskin O, Kalkan Ç, Karakaya F, Çalişkan A, Karatayli E, Karatayli S, Bozdayi AM, Koh C, Heller T, Idilman R, Glenn JS. Optimizing lonafarnib treatment for the management of chronic delta hepatitis: The LOWR HDV-1 study. Hepatology. 2018;67:1224-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Roche B, Samuel D. Liver transplantation in delta virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:245-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Rifai K, Wedemeyer H, Rosenau J, Klempnauer J, Strassburg CP, Manns MP, Tillmann HL. Longer survival of liver transplant recipients with hepatitis virus coinfections. Clin Transplant. 2007;21:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV. High genetic barrier nucleos(t)ide analogue(s) for prophylaxis from hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:353-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Chun J, Kim W, Kim BG, Lee KL, Suh KS, Yi NJ, Park KU, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Lee HS. High viremia, prolonged Lamivudine therapy and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma predict posttransplant hepatitis B recurrence. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1649-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | de Villa VH, Chen YS, Chen CL. Hepatitis B core antibody-positive grafts: recipient's risk. Transplantation. 2003;75:S49-S53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Muhammad H, Hammami MB, Ting PS, Simsek C, Saberi B, Gurakar. Can HCV Viremic Organs Be Used in Liver Transplantation to HCV Negative Recipients? OBM Hepatol and Gastroenterol. 2020;4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 54. | Rizzetto M, Macagno S, Chiaberge E, Verme G, Negro F, Marinucci G, di Giacomo C, Alfani D, Cortesini R, Milazzo F. Liver transplantation in hepatitis delta virus disease. Lancet. 1987;2:469-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ottobrelli A, Marzano A, Smedile A, Recchia S, Salizzoni M, Cornu C, Lamy ME, Otte JB, De Hemptinne B, Geubel A. Patterns of hepatitis delta virus reinfection and disease in liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1649-1655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Samuel D, Muller R, Alexander G, Fassati L, Ducot B, Benhamou JP, Bismuth H. Liver transplantation in European patients with the hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1842-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 837] [Cited by in RCA: 746] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 57. | Adil B, Fatih O, Volkan I, Bora B, Veysel E, Koray K, Cemalettin K, Burak I, Sezai Y. Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis D Virus Recurrence in Patients Undergoing Liver Transplantation for Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis B Virus Plus Hepatitis D Virus. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2119-2123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Idilman R, Akyildiz M, Keskin O, Gungor G, Yilmaz TU, Kalkan C, Dayangac M, Cinar K, Balci D, Hazinedaroglu S, Tokat Y. The long-term efficacy of combining nucleos(t)ide analog and low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin on post-transplant hepatitis B virus recurrence. Clin Transplant. 2016;30:1216-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Serin A, Tokat Y. Recurrence of Hepatitis D Virus in Liver Transplant Recipients With Hepatitis B and D Virus-Related Chronic Liver Disease. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:2457-2460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Lima DS, Murad Júnior AJ, Barreira MA, Fernandes GC, Coelho GR, Garcia JHP. LIVER TRANSPLANTATION IN HEPATITIS DELTA: SOUTH AMERICA EXPERIENCE. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55:14-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Samuel D, Zignego AL, Reynes M, Feray C, Arulnaden JL, David MF, Gigou M, Bismuth A, Mathieu D, Gentilini P. Long-term clinical and virological outcome after liver transplantation for cirrhosis caused by chronic delta hepatitis. Hepatology. 1995;21:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |