Published online Oct 27, 2021. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i10.1405

Peer-review started: April 11, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: June 23, 2021

Accepted: September 23, 2021

Article in press: September 23, 2021

Published online: October 27, 2021

Processing time: 194 Days and 13.2 Hours

Despite significant advancements in liver transplantation (LT) surgical procedures and perioperative care, post-LT biliary complications (BCs) remain a significant source of morbidity, mortality, and graft failure. In addition, data are conflicting regarding the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of LT recipients. Thus, the success of LT should be considered in terms of both the survival and recovery of HRQoL.

To assess the impact of BCs on the HRQoL of live-donor LT recipients (LDLT-Rs).

We retrospectively analysed data for 25 LDLT-Rs who developed BCs post-LT between January 2011 and December 2016 at our institution. The Short Form 12 version 2 (SF 12v2) health survey was used to assess their HRQoL. We also included 25 LDLT-Rs without any post-LT complications as a control group.

The scores for HRQoL of LDLT-Rs who developed BCs were significantly higher than the norm-based scores in the domains of physical functioning (P = 0.003), role-physical (P < 0.001), bodily pain (P = 0.003), general health (P = 0.004), social functioning (P = 0.005), role-emotional (P < 0.001), and mental health (P < 0.001). No significant difference between the two groups regarding vitality was detected (P = 1.000). The LDLT-Rs with BCs had significantly lower scores than LDLT-Rs without BCs in all HRQoL domains (P < 0.001) and the mental (P < 0.001) and physical (P = 0.0002) component summary scores.

The development of BCs in LDLT-Rs causes a lower range of improvement in HRQoL.

Core Tip: We retrospectively analysed data for 25 Live-donor liver transplantation recipients (LDLT-Rs) with biliary complications (BCs) and described their health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using the Short Form 12 version 2 health survey. All scores for HRQoL domains of LDLT-Rs with BCs were significantly higher than the norm-based scores except for vitality. The LDLT-Rs with BCs had significantly lower scores than LDLT-Rs without BCs in all HRQoL domains (P < 0.001) and in the mental (P < 0.001) and physical (P = 0.0002) component summary scores. We conclude that the development of BCs in LDLT-Rs causes a lower range of improvement in HRQoL.

- Citation: Guirguis RN, Nashaat EH, Yassin AE, Ibrahim WA, Saleh SA, Bahaa M, El-Meteini M, Fathy M, Dabbous HM, Montasser IF, Salah M, Mohamed GA. Impact of biliary complications on quality of life in live-donor liver transplant recipients. World J Hepatol 2021; 13(10): 1405-1416

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v13/i10/1405.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v13.i10.1405

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional model reflecting the domains of social, mental, emotional, and physical health[1,2]. More than 50 different HRQoL tools have been used in liver transplant (LT) research[3], and no golden standard instrument has existed until now[4]. These tools can be classified into generic and disease-specific tools[3,5]. Generic HRQoL tools, of which the validated Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey is the most frequently used for evaluating LT recipients, allow assessments across various medical conditions and health states[6,7].

Short Form 12 version 2 (SF-12v2) is a validated concise version of the SF-36 version 2 (SF-36v2) with only 12 questions[8,9]. Similar to the SF-36v2, it evaluates the same eight dimensions of HRQoL covering the previous 4 wk: General health, bodily pain, physical functioning, role physical, vitality, role emotional, mental health, and social functioning. Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores were created from patient responses[10]. The sum of scores ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates the worst state of health and 100 indicates the best state of health[10,11].

The data are conflicting regarding the HRQoL of LT recipients. The heterogeneity between studies regarding the type of graft, diversity of included patients, and health survey precludes definitive conclusions[4,12]. In addition, an overlap exists between the primary liver disease and LT process with diverse events during peri- and postoperative management.

The global assessment of HRQoL after LT usually confirms improvement compared with pretransplant status[13]; however, it may remain suboptimal compared to the general population due to post-LT complications, recurrence of primary liver disease, or adverse effects of immunosuppressants[14-17]. In addition, cirrhosis leads to loss of muscle mass, sarcopenia, malnutrition, and physical impairment that manifest as physical frailty, increasing the risk of pretransplant mortality[18-20] and delayed improvement of physical functioning post-LT[21-23].

Fatigue affects up to 50% of patients with chronic liver disease; moreover, it demonstrates a significant association with poor HRQoL[24,25]. It also affects up to 60% of LT recipients[26]. It is a complex symptom that may be influenced by physical and mental states, including poor sleep quality, anxiety, and depression[27].

The LT candidates often have impaired HRQoL with a high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms[28,29]. Moreover, LT was considered as post-traumatic stress disorder and was also found to be associated with anxiety and depression, which may further impair the HRQoL of LT recipients[30-33].

In the light of the above, HRQoL should be considered in terms of the outcome after LT[34,35]. Hence, we aimed to assess the impact of biliary complications (BCs) on the HRQoL of live-donor LT recipients (LDLT-Rs).

We retrospectively analysed all LDLT-Rs at Ain Shams Centre for Organ Transplantation, Ain Shams Specialised Hospital, Cairo, Egypt, between January 2011 and December 2016. During this period, 215 adult patients underwent right-lobe LDLT at our centre. We included LDLT-Rs who developed BCs post-LT. We excluded LDLT-Rs with any of the following situations: cholestatic liver diseases (primary biliary cirrhosis or primary sclerosing cholangitis), vascular complications, acute or chronic rejection, recurrent hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, graft failure, failure to follow up for at least one year post-LT, or patients who refused to participate in the research. As a result, 25 LDLT-Rs with BCs were included in the final analysis. We enrolled 25 LDLT-Rs who did not develop any post-LT complications as a control group. LT recipients were assessed at least 12 months post-LT, with median follow up duration of 5.5 years (range: 12 mo - 8 years).

This study was performed per the ethical principles of the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University (No: FMASU MD 187/2016), which waived the requirement of informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the research.

Eligible LDLT-Rs were invited to fulfil the SF-12v2 questionnaire during follow-up visits after obtaining verbal consent. We used anonymous questionnaires to ensure strict confidentiality. The SF-12v2 includes 12 questions: one question on general health perceptions, two questions concerning physical functioning, two questions on role limitations because of physical health problems, one question on bodily pain, one question on vitality, two questions on role limitations, one question on social functioning, and two questions on general mental health.

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (v. 23; IBM Corp., Armonk, New York). Nonparametric numerical variables are presented as the median and interquartile range. Nominal variables are presented as the number and percentage. Ordinal data were analysed using the chi-squared test for trends. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

This study included 25 adult right-lobe LDLT-Rs who experienced BCs. At the time of LT, the mean age of the recipients was 52 ± 7 years, and 19 (76%) recipients were male. Cirrhosis due to HCV was the most common indication for LT in 21 patients (84%; Tables 1 and 2).

| Variable | n (%) | |

| Indication of liver transplantation | HCV | 21 (84) |

| HBV | 1 (4) | |

| Combined HCV and HBV | 1 (4) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2 (8) | |

| Donors’ gender | Male | 17 (68) |

| Female | 8 (32) | |

| Recipients’ gender | Male | 19 (76) |

| Female | 6 (24) | |

| Immunosuppressant | Tacrolimus | 22 (88) |

| Cyclosporine | 3 (12) | |

| Biliary leakage | - | 7 (28) |

| + | 18 (72) | |

| Need of pigtail catheter for biloma (total = 18) | - | 15 (83.3) |

| + | 3 (16.6) | |

| Biliary infection | - | 0 (0) |

| + | 25 (100) | |

| Frequency of biliary infection (total = 25) | 1-2 Episodes | 16 (64) |

| ≥ 3 Episodes | 9 (36) | |

| Biliary stricture | - | 5 (20) |

| + | 20 (80) | |

| Frequency of biliary stricture (total = 20) | 1-2 Episodes | 13 (65) |

| ≥ 3 Episodes | 7 (28) | |

| Need for ERCP | - | 5 (20) |

| + | 20 (80) | |

| Frequency of ERCP | 1-2 ERCP | 13 (65) |

| ≥ 3 ERCP | 7 (28) | |

| Need for PTC | - | 22 (88) |

| + | 3 (12) | |

| Frequency of PTC | 1 PTC | 2 (66.6) |

| 2 PTC | 1 (33.3) | |

| Surgical intervention for stricture | - | 19 (95) |

| + | 1 (5) | |

| Admission related to biliary complications | - | 0 (0) |

| + | 25 (100) | |

| Early biliary infection (total = 25) | - | 2 (8) |

| + | 23 (92) | |

| Early biliary stricture (total = 20) | - | 17 (68) |

| + | 8 (32) |

| Variable | Data |

| MELD score | 15 ± 3 |

| Child score | 9 ± 2 |

| Donors’ age (yr) | 30 ± 4 |

| Donors’ BMI (kg/m2) | 25 ± 4 |

| Recipient's age (yr) | 52 ± 7 |

| Recipient's BMI (kg/m2) | 27 ± 6 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.9 (2-3.9) |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.6 (0.9-2.3) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 190 ± 49 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (IU/L) | 100 (50-130) |

| Platelets (109/L) | 75 ± 31 |

| Cold ischemia time (min) | 48 ± 25 |

| Warm ischemia time (min) | 47 ± 23 |

| Graft arterialization time (min) | 145 ± 53 |

| Time to biliary infection (d) | 13 (11-36) |

| Time to biliary stricture (d) | 130 (120-190) |

Among the 25 LDLT-Rs included in this study, minor biliary leakage occurred in 15 recipients (83.3%) and stopped spontaneously without further management. In only three (16.6%) recipients, pigtail insertion and further interventional management were needed. Moreover, 25 recipients developed a biliary infection, mainly occurring early (23; 92%) and in one to two episodes in 16 (64%) recipients (Table 1). Furth

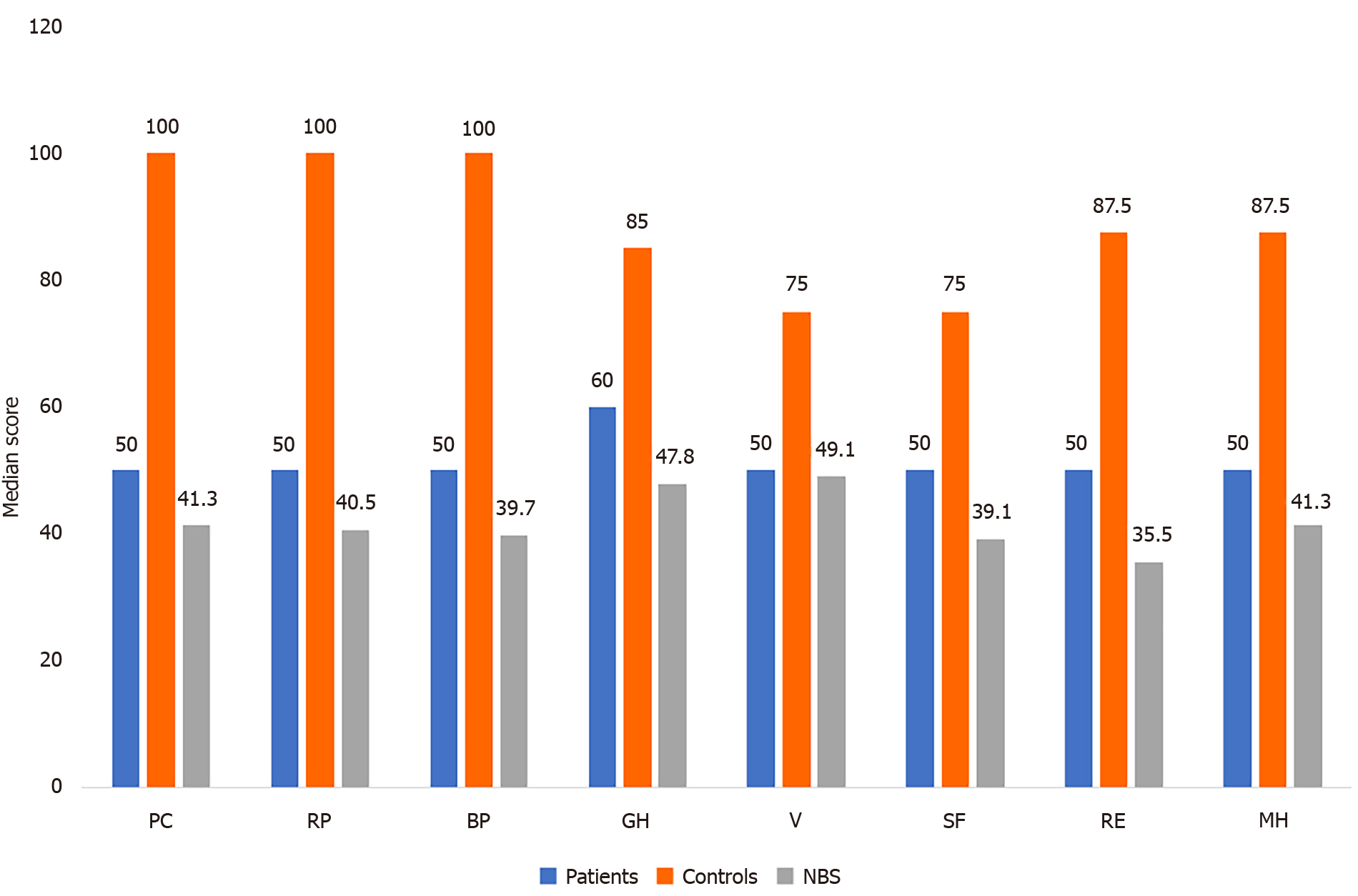

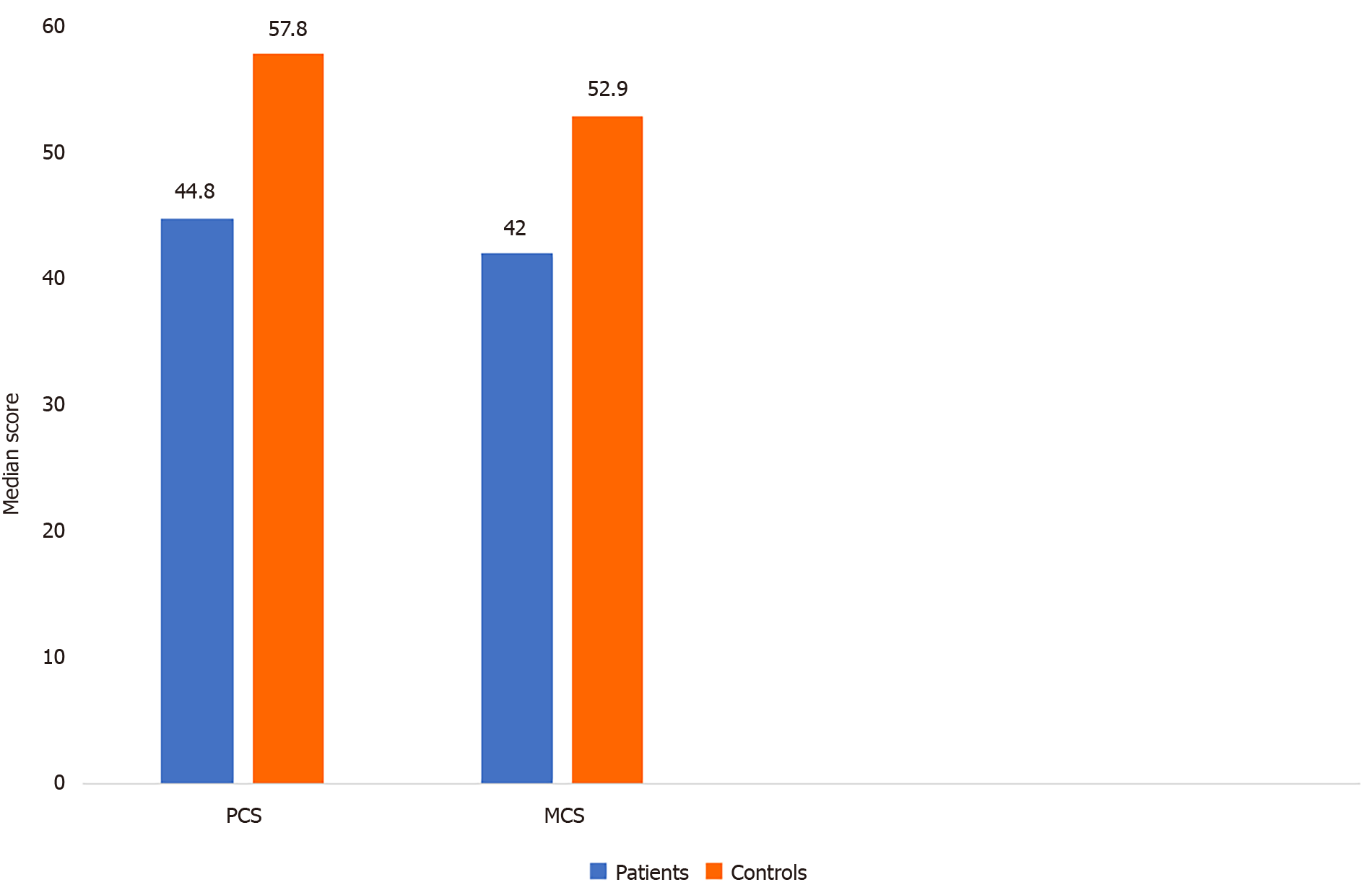

The scores of HRQoL of LDLT-Rs with BCs were significantly higher than the norm-based scores in the domains of physical functioning (P = 0.003), role-physical (P < 0.001), bodily pain (P = 0.003), general health (P = 0.004), social functioning (P = 0.005), role-emotional (P < 0.001), and mental health (P < 0.001). In contrast, no significant difference was found between the two groups regarding vitality (P = 1.000; Table 3 and Figure 1). The LDLT-Rs with BCs had significantly lower scores than LDLT-Rs without BCs in all HRQoL domains (P < 0.001) and in the mental (P < 0.001) and physical (P = 0.0002) component summary scores (Tables 4 and 5; Figures 1 and 2).

| HRQoL score | LDLT-R with BC | NBS score | P value1 |

| Physical functioning | 50 (50-75) | 41.3 (41.3-49.2) | 0.003 |

| Role physical | 50 (31.3-75) | 40.5 (34.2-49) | 0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 50 (50-75) | 39.7 (39.7-48.7) | 0.003 |

| General health | 60 (60-85) | 47.8 (47.8-57.7) | 0.004 |

| Vitality | 50 (25-50) | 49.1 (39.2-49.1) | 1.000 |

| Social functioning | 50 (50-50) | 39.1 (39.1-39.1) | 0.005 |

| Role emotion | 50 (37.5-75) | 35.5 (30.3-45.9) | < 0.001 |

| Mental health | 50 (50-62.5) | 41.3 (41.3-47) | 0.001 |

| HRQoL domain | Patients (n = 25) | Controls (n = 25) | P value1 |

| Physical functioning | 50 (50-75) | 100 (100-100) | < 0.001 |

| Role physical | 50 (31.3-75) | 100 (87.5-100) | < 0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 50 (50-75) | 100 (100-100) | < 0.001 |

| General health | 60 (60-85) | 85 (85-85) | < 0.001 |

| Vitality | 50 (25-50) | 75 (75-87.5) | < 0.001 |

| Social functioning | 50 (50-50) | 75 (75-100) | < 0.001 |

| Role emotion | 50.0 (37.5-75) | 87.5 (75-100) | < 0.001 |

| Mental health | 50 (50-62.5) | 87.5 (75-87.5) | < 0.001 |

| PCS | 44.8 (41.7-52.9) | 57.8 (55.2-59) | < 0.001 |

| MCS | 42 (35.6-45.2) | 52.9 (50.2-57.9) | < 0.001 |

| Variable | NBS | Patients (n = 25), % | Control (n = 25) , % | P value1 |

| Physical component summary score | At or above | 11 (44) | 25 (100) | 0.0002 |

| Below | 8 (32) | 0 (0) | ||

| Far below | 6 (24) | 0 (0) | ||

| Mental component summary score | At or above | 7 (28) | 24 (96) | < 0.0001 |

| Below | 7 (28) | 1 (4) | ||

| Far below | 11 (44) | 0 (0) |

Despite the considerable advances in LT surgical techniques and perioperative care, post-LT BCs remain a significant source of morbidity, mortality, and graft failure[36]. To our knowledge, no previous study has specifically assessed the impact of BCs on the HRQoL of LDLT-Rs. In our study, LDLT-Rs with BCs had significantly higher HRQoL domain scores except for the vitality domain than norm-based scores; however, those patients gained a significantly lower range of improvement in HRQoL domains with lower MCS and PCS scores than those without BCs. This result can be attributed to more prolonged and frequent hospital admission and expectation reduction with anxiety, stress, and depression[37]. In agreement with the current results, the published literature has observed the positive effects of LT on the recipients’ HRQoL[12,37-40].

Similar to the present study[41], other authors have assessed the LT recipients’ HRQoL using the WHOQOLBREF questionnaire[42] and Transplant Effects Questionnaire[43] and concluded that LT recipients, especially those who received LDLT, reported the highest level of HRQoL in all four dimensions of HRQoL in comparison to those with other organ transplantation.

In partial agreement with the current study, a review of 32 studies and 5402 patients found that the overall HRQoL scores of LT recipients remain improved and equivalent to the general population in the long term. However, physical functioning continues to be inferior to the general population despite a noticeable improvement from preoperative physical functioning[4]. Similarly, a review article of 31 publications reported improved overall HRQoL and physical functioning in deceased donor LT (DDLT) adult recipients during the first 2 years, which remains stable in the long term but does not reach the level of the general population[35]. Additionally, Sullivan et al[44] assessed the HRQoL two decades after DDLT using the SF-12 survey. In adult survivors, the MCS score (54.6) was equivalent to that of the general population; however, the PCS score (39.3) remained below average. This outcome can be explained by the presence of comorbidities, primary liver disease severity, postoperative morbidity, and graft type[20,33]. Additionally, Dunn et al[45] reported that group exercise activities were correlated with improved physical function, mental health, and HRQoL, independent of comorbidities, for up to 5 years after LT. Therefore, physical activity should be encouraged after LT[46].

In a study by Casanovas et al[47], the SF-36 scores of 156 LT candidates were assessed pre- and post-LT. They observed significantly lower patient baseline scores in all HRQoL domains than general population scores, especially in physical health. As early as 3 months till 1-year post-LT, they detected improvement in all SF-36 domains except vitality and social functioning, revealing no significant improvement. Moreover, sleeping problems were observed at the baseline and persisted post-LT. The poor sleep quality frequently noted in cirrhotic patients is known to cause fatigue and impair cognitive and physical functions[48].

In contrast to our results, Domingos et al[37] retrospectively assessed the HRQoL of 93 DDLT recipients who survived 10 years post-LT using the SF-36 survey and observed that LT recipients had lower mental health scores than the general population. In all other domains, LT recipients had similar (emotional limitations, pain, and general health status) or superior (physical limitations, social aspects, functional capacity, and vitality) scores than the general population. In addition, Dąbrowska-Bender et al[15] assessed the SF-36 health survey in 121 DDLT recipients and observed no change in mental health score, whereas significant physical impairment was reported by 18.18% of the recipients.

In a study by Annema et al[30], LT had a beneficial effect on the mental health of LT recipients by ameliorating anxiety and depression symptom severity. However, recipients with persistent symptoms of anxiety and depression experienced a negative effect on HRQoL and therapeutic adherence. They also observed that persistent anxiety and depression were correlated with the development of BCs and the duration of the hospital stay. Similarly, in another report[49], the HRQoL of 82 LT recipients was retrospectively assessed, finding 94% reported high mean scores on HRQoL, the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire, and adherence to medications. Conversely, patients with a low HRQoL reported anxiety, depression, fatigue, slowing pace, and physical limitations, suggesting that LT recipients who fail to adapt to their post-LT state experienced a decreased ability to tolerate physical symptoms and post-LT complications[50]. Other causes for lower mental health scores post-LT are the worry regarding medication side effects, hepatic disease recurrence, and other potential complications[51].

Candidates for LT may have overly optimistic anticipations for post-LT improve

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and small sample size. More research is required to define the predictors of HRQoL and plan multidisciplinary strategies for HRQoL improvement in LT recipients. According to the current literature, HRQoL should be integrated into the clinical care of LT[53].

We conclude that the development of BCs in LDLT-Rs causes a lower range of improvement in HRQoL.

Despite the considerable advances in liver transplantation (LT) surgical techniques and perioperative care, post-LT biliary complications (BCs) remain a significant source of morbidity, mortality, and graft failure. Due to the current high survival rates of LT, the focus has shifted to improving the quality of life of LT recipients.

The data are conflicting regarding the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of LT recipients.

To assess the impact of BCs on the HRQoL of live-donor LT recipients (LDLT-Rs).

We retrospectively analysed data for 25 LDLT-Rs with BCs and described their HRQoL through the Short Form 12 version 2 (SF-12v2) health survey compared to 25 LDLT-Rs without post-LT complications.

The scores of HRQoL of LDLT-Rs with BCs were significantly higher than the norm-based scores in all HRQoL domains except vitality. The LDLT-Rs with BCs had significantly lower scores than LDLT-Rs without BCs in all HRQoL domains (P < 0.001) and in the mental (P < 0.001) and physical (P = 0.0002) component summary scores.

The development of BCs in LDLT-Rs causes a lower range of improvement in HRQoL.

The assessment of HRQoL should be integrated into the clinical care of LT recipients. Identifying the determinants of HRQoL could improve the management plan of these patients through a multidisciplinary approach.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dambrauskas Z S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being | Healthy People 2020. [cited 20 February 2021]. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health measures/Health-Related-Quality-of-Life-and-Well-Being. |

| 2. | Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenæs R, Andersen JR, Andersen MH, Beisland E, Borge CR, Engebretsen E, Eisemann M, Halvorsrud L, Hanssen TA, Haugstvedt A, Haugland T, Johansen VA, Larsen MH, Løvereide L, Løyland B, Kvarme LG, Moons P, Norekvål TM, Ribu L, Rohde GE, Urstad KH, Helseth S; LIVSFORSK network. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:2641-2650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 81.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jay CL, Butt Z, Ladner DP, Skaro AI, Abecassis MM. A review of quality of life instruments used in liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51:949-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yang LS, Shan LL, Saxena A, Morris DL. Liver transplantation: a systematic review of long-term quality of life. Liver Int. 2014;34:1298-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Saab S, Ng V, Landaverde C, Lee SJ, Comulada WS, Arevalo J, Durazo F, Han SH, Younossi Z, Busuttil RW. Development of a disease-specific questionnaire to measure health-related quality of life in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:567-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | RAND Corporation. 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) Scoring Instructions. [cited 20 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form/scoring.html. |

| 7. | Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11319] [Cited by in RCA: 12808] [Article Influence: 441.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | SF-12 and SF-12v2 Health Survey. [cited 20 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.qualitymetric.com/health-surveys/the-sf-12v2-health-survey/. |

| 10. | Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (with a supplement Documenting Version 1). Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated, 2002. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maruish ME. User’s Manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey. 3rd ed. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Incorporated, 2012. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | McLean KA, Drake TM, Sgrò A, Camilleri-Brennan J, Knight SR, Ots R, Adair A, Wigmore SJ, Harrison EM. The effect of liver transplantation on patient-centred outcomes: a propensity-score matched analysis. Transpl Int. 2019;32:808-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Burra P, Ferrarese A, Feltrin G. Quality of life and adherence in liver transplant recipients. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2018;64:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Burra P, Ferrarese A. Health-related quality of life in liver transplantation: another step forward. Transpl Int. 2019;32:792-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dąbrowska-Bender M, Kozaczuk A, Pączek L, Milkiewicz P, Słoniewski R, Staniszewska A. Patient Quality of Life After Liver Transplantation in Terms of Emotional Problems and the Impact of Sociodemographic Factors. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:2031-2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, Guerrero-Misas M, Thorburn D, Davidson BR, Tsochatzis E, Gurusamy KS. Maintenance immunosuppression for adults undergoing liver transplantation: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD011639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Amodio P, Salari L, Montagnese S, Schiff S, Neri D, Bianco T, Minazzato L. Hepatitis C virus infection and health-related quality of life. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2295-2299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bhanji RA, Takahashi N, Moynagh MR, Narayanan P, Angirekula M, Mara KC, Dierkhising RA, Watt KD. The evolution and impact of sarcopenia pre- and post-liver transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:807-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ooi PH, Hager A, Mazurak VC, Dajani K, Bhargava R, Gilmour SM, Mager DR. Sarcopenia in Chronic Liver Disease: Impact on Outcomes. Liver Transpl. 2019;25:1422-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tandon P, Montano-Loza AJ eds. Frailty and Sarcopenia in Cirrhosis. The Basics, the Challenges and the Future. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2019: 1-279. |

| 21. | Lai JC, Segev DL, McCulloch CE, Covinsky KE, Dodge JL, Feng S. Physical frailty after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1986-1994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dasarathy S, Merli M. Sarcopenia from mechanism to diagnosis and treatment in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1232-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Davuluri G, Krokowski D, Guan BJ, Kumar A, Thapaliya S, Singh D, Hatzoglou M, Dasarathy S. Metabolic adaptation of skeletal muscle to hyperammonemia drives the beneficial effects of l-leucine in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2016;65:929-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Barboza KC, Salinas LM, Sahebjam F, Jesudian AB, Weisberg IL, Sigal SH. Impact of depressive symptoms and hepatic encephalopathy on health-related quality of life in cirrhotic hepatitis C patients. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31:869-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jopson L, Dyson JK, Jones DE. Understanding and Treating Fatigue in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:131-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Elliott C, Frith J, Pairman J, Jones DE, Newton JL. Reduction in functional ability is significant postliver transplantation compared with matched liver disease and community dwelling controls. Transpl Int. 2011;24:588-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kang SH, Choi Y, Han HS, Yoon YS, Cho JY, Kim S, Kim KH, Hyun IG, Shehta A. Fatigue and weakness hinder patient social reintegration after liver transplantation. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018;24:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Paglione HB, Oliveira PC, Mucci S, Roza BA, Schirmer J. Quality of life, religiosity, and anxiety and depressive symptoms in liver transplantation candidates. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2019;53:e03459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nusrat S, Khan MS, Fazili J, Madhoun MF. Cirrhosis and its complications: evidence based treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5442-5460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 30. | Annema C, Drent G, Roodbol PF, Stewart RE, Metselaar HJ, van Hoek B, Porte RJ, Ranchor AV. Trajectories of Anxiety and Depression After Liver Transplantation as Related to Outcomes During 2-Year Follow-Up: A Prospective Cohort Study. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:174-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Saracino RM, Jutagir DR, Cunningham A, Foran-Tuller KA, Driscoll MA, Sledge WH, Emre SH, Fehon DC. Psychiatric Comorbidity, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Mental Health Service Utilization Among Patients Awaiting Liver Transplant. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Annema C, Drent G, Roodbol PF, Metselaar HJ, Van Hoek B, Porte RJ, Schroevers MJ, Ranchor AV. A prospective cohort study on posttraumatic stress disorder in liver transplantation recipients before and after transplantation: Prevalence, symptom occurrence, and intrusive memories. J Psychosom Res. 2017;95:88-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen PX, Yan LN, Wang WT. Health-related quality of life of 256 recipients after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5114-5121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2016;64:433-485. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Onghena L, Develtere W, Poppe C, Geerts A, Troisi R, Vanlander A, Berrevoet F, Rogiers X, Van Vlierberghe H, Verhelst X. Quality of life after liver transplantation: State of the art. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:749-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 36. | Chang JH, Lee I, Choi MG, Han SW. Current diagnosis and treatment of benign biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1593-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Domingos MF, Coelho JCU, Nogueira IR, Parolin MB, Matias JEF, De Freitas ACT, Zeni Neto C, Ramos EJB. Quality of Life after 10 Years of Liver Transplantation. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020;29:611-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Jover-Aguilar M, Martínez-Alarcón L, Ramis G, Gago FA, Pons JA, Ríos A, Febrero B, García CC, Hiciano Guillermo AI, Ramírez P. Self-Esteem Related to Quality of Life in Patients Over 60 Years Old Who Received an Orthotopic Liver Transplantation More Than 10 Years Ago. Transplant Proc. 2020;52:562-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Beekman L, Berzigotti A, Banz V. Physical Activity in Liver Transplantation: A Patient's and Physicians' Experience. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1729-1734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Legendre C, Viebahn R, Crespo M, Dor F, Gustafsson B, Samuel U, Karam V, Binet I, Aberg F, De Geest S, Moes DJAR, Tonshoff B, Oppenheimer F, Asberg A, Halleck F, Loupy A, Suesal C. Beyond Survival in Solid Organ Transplantation: A Summary of Expert Presentations from the Sandoz 6th Standalone Transplantation Meeting, 2018. Transplantation. 2019;103:S1-S13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tarabeih M, Bokek-Cohen Y, Azuri P. Health-related quality of life of transplant recipients: a comparison between lung, kidney, heart, and liver recipients. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:1631-1639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | WHO. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment; Field trial version. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. [cited 20 February 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf. |

| 43. | Ziegelmann JP, Griva K, Hankins M, Harrison M, Davenport A, Thompson D, Newman SP. The Transplant Effects Questionnaire (TxEQ): The development of a questionnaire for assessing the multidimensional outcome of organ transplantation - example of end stage renal disease (ESRD). Br J Health Psychol. 2002;7:393-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sullivan KM, Radosevich DM, Lake JR. Health-related quality of life: two decades after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:649-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Dunn MA, Rogal SS, Duarte-Rojo A, Lai JC. Physical Function, Physical Activity, and Quality of Life After Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:702-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Neale J, Smith AC, Bishop NC. Effects of Exercise and Sport in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:273-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Casanovas T, Herdman M, Chandía A, Peña MC, Fabregat J, Vilallonga JS. Identifying Improved and Non-improved Aspects of Health-related Quality of Life After Liver Transplantation Based on the Assessment of the Specific Questionnaire Liver Disease Quality of Life. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:132-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Stewart CA, Auger RR, Enders FT, Felmlee-Devine D, Smith GE. The effects of poor sleep quality on cognitive function of patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9:207-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 509] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Girgenti R, Tropea A, Buttafarro MA, Ragusa R, Ammirata M. Quality of Life in Liver Transplant Recipients: A Retrospective Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Burra P, Germani G. Long-term quality of life for transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2013;19 Suppl 2:S40-S43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Sánchez-Martín M, Borda-Mas M, Avargues-Navarro ML, Gómez-Bravo MÁ, Conrad R. Spanish Adaptation and Validation of the Transplant Effects Questionnaire (TxEQ-Spanish) in Liver Transplant Recipients and Its Relationship to Posttraumatic Growth and Quality of Life. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Åberg F. Quality of life after liver transplantation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;46-47:101684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |