Published online Jun 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i6.312

Peer-review started: January 7, 2020

First decision: February 27, 2020

Revised: May 10, 2020

Accepted: May 27, 2020

Article in press: May 27, 2020

Published online: June 27, 2020

Processing time: 173 Days and 0.4 Hours

Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis (LPAC) syndrome is a very particular form of biliary lithiasis with no excess of cholesterol secretion into bile, but a decrease in phosphatidylcholine secretion, which is responsible for stones forming not only in the gallbladder, but also in the liver. LPAC syndrome may be underreported due to a lack of testing resulting from insufficient awareness among clinicians.

To describe the clinical and radiological characteristics of patients with LPAC syndrome to better identify and diagnose the disease.

We prospectively evaluated all patients aged over 18 years old who were consulted or hospitalized in two hospitals in Paris, France (Bichat University Hospital and Croix-Saint-Simon Hospital) between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018. All patients whose profiles led to a clinical suspicion of LPAC syndrome underwent a liver ultrasound examination performed by an experienced radiologist to confirm the diagnosis of LPAC syndrome. Twenty-four patients were selected. Data about the patients’ general characteristics, their medical history, their symptoms, and their blood tests results were collected during both their initial hospitalization and follow-up. Cytolysis and cholestasis were expressed compared to the normal values (N) of serum aspartate and alanine transaminase activities, and to the normal value of alkaline phosphatase level, respectively. The subjects were systematically reevaluated and asked about their symptoms 6 mo after inclusion in the study through an in-person medical appointment or phone call. Genetic testing was not performed systematically, but according to the decision of each physician.

Most patients were young (median age of 37 years), male (58%), and not overweight (median body mass index was 24). Many had a personal history of acute pancreatitis (54%) or cholecystectomy (42%), and a family history of gallstones in first-degree relatives (30%). LPAC syndrome was identified primarily in patients with recurring biliary pain (88%) or after a new episode of acute pancreatitis (38%). When present, cytolysis and cholestasis were not severe (2.8N and 1.7N, respectively) and disappeared quickly. Interestingly, four patients from the same family were diagnosed with LPAC syndrome. At ultrasound examination, the most frequent findings in intrahepatic bile ducts were comet-tail artifacts (96%), microlithiasis (83%), and acoustic shadows (71%). Computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging were performed on 15 and three patients, respectively, but microlithiasis was not detected. Complications of LPAC syndrome required hospitalizing 18 patients (75%) in a conventional care unit for a mean duration of 6.8 d. None of them died. Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was effective and well-tolerated in almost all patients (94%) with a rapid onset of action (3.4 wk). Twelve patients’ (67%) adherence to UDCA treatment was considered “good.” Five patients (36%) underwent cholecystectomy (three of them were treated both by UDCA and cholecystectomy). Despite UDCA efficacy, biliary pain recurred in five patients (28%), three of whom adhered well to treatment guidelines.

LPAC syndrome is easy to diagnose and treat; therefore, it should no longer be overlooked. To increase its detection rate, all patients who experience recurrent biliary symptoms following an episode of acute pancreatitis should undergo an ultrasound examination performed by a radiologist with knowledge of the disease.

Core tip: Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis (LPAC) syndrome is considered rare, but it may be underreported due to a lack of testing resulting from insufficient awareness among physicians, radiologists, and digestive surgeons. This study describes the clinical and radiological characteristics of patients with LPAC syndrome, which helps clinicians better diagnose and treat the disease. Diagnosis is easily made via ultrasound imaging performed on patients with typical recurring biliary symptoms, and medical treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid is rapidly effective and well-tolerated. LPAC syndrome is straightforward to diagnose and treat; therefore, it should no longer be overlooked.

- Citation: Gille N, Karila-Cohen P, Goujon G, Konstantinou D, Rekik S, Bécheur H, Pelletier AL. Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis syndrome: A rare cause of acute pancreatitis that should not be neglected. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(6): 312-322

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i6/312.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i6.312

Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis (LPAC) syndrome is a very particular form of biliary lithiasis that was first described by Rosmorduc et al[1] in 2001. Contrary to what occurs in “common” cholelithiasis, there is no excess of cholesterol secretion into bile in this syndrome, but a decrease in phosphatidylcholine secretion. Phosphatidylcholine is the major phospholipid in human bile; i.e., it forms micelles to solubilize cholesterol and permit its transportation. With a low phospholipid content, the bile is oversaturated with cholesterol crystals that precipitate to form microscopic and macroscopic stones not only in the gallbladder but also in the liver[2]. A decrease in phosphatidylcholine secretion is caused by a mutation of ATP-binding cassette, subfamily B, member 4 (ABCB4) gene encoding the bile canalicular protein Multidrug resistance 3 (MDR3), which is the phosphatidylcholine translocator across the canalicular membrane of the hepatocyte[3].

The prevalence of LPAC syndrome has not been evaluated with precision, but it affects around 5% of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis[2]. Although only a few studies have described patients with this disorder due to its rarity and its recent discovery, several common characteristics have been identified. LPAC syndrome usually manifests through biliary symptoms or complications (e.g., biliary pain, acute pancreatitis, cholecystitis, or cholangitis) that occur in young patients who are not overweight. These symptoms often recur after cholecystectomy. Moreover, patients frequently report a family history of cholelithiasis, or a personal history of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in women[3].

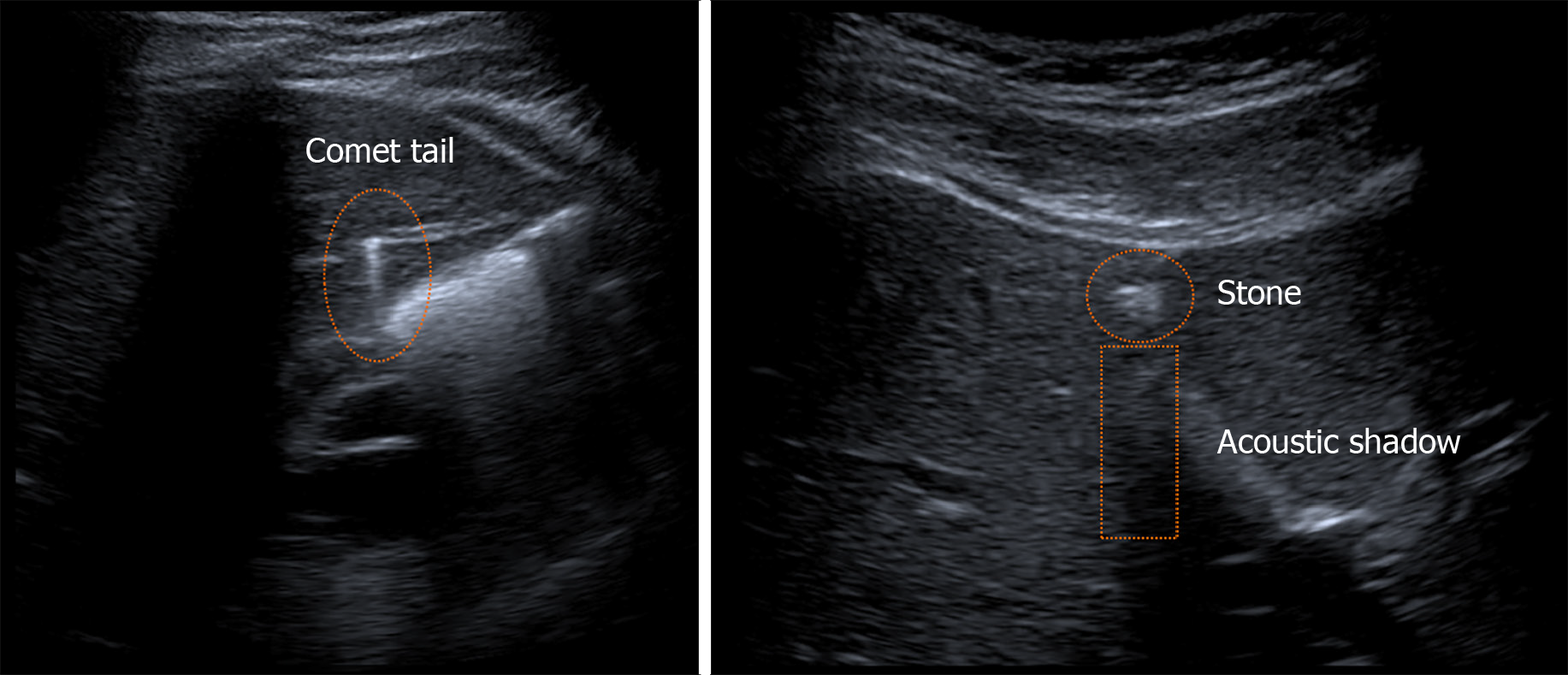

Ultrasound examination of the liver is essential for diagnosis because it can reveal intrahepatic stones, which appear as heterogeneous and echoic foci with acoustic shadows centered on the intrahepatic ducts, intrahepatic microlithiasis, or comet-tail artifacts due to ultrasound reverberation[4].

Although the reason behind its efficacy is not completely understood, treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) seems to diminish symptoms of LPAC syndrome in the majority of cases[1,3,5]. Such treatment is typically carried out on a long-term basis, but it remains unclear whether the therapy should be administered throughout a patient’s entire life. Improving the understanding of this syndrome will facilitate the screening and treatment of patients.

LPAC syndrome may be underreported due to a lack of testing resulting from insufficient awareness among physicians, radiologists, and digestive surgeons. The aim of this study was to describe the clinical and radiological characteristics of patients with LPAC syndrome to better identify and diagnose the disease.

We prospectively evaluated all patients aged over 18 years old who were consulted or hospitalized in two hospitals in Paris, France (Bichat University Hospital and Croix-Saint-Simon Hospital) between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018. All patients whose profiles led to a clinical suspicion of LPAC syndrome underwent a liver ultrasound examination performed by an experienced radiologist to confirm the diagnosis of LPAC syndrome.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had an acute pancreatitis with any other etiology, if they suffered from chronic alcoholism or, if at the ultrasound examination, their liver was dysmorphic or had massive steatosis.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data about the patients’ general characteristics, their medical history, their symptoms, and their blood tests results, were collected during both their initial hospitalization and follow-up. Cytolysis and cholestasis were expressed compared to the normal values (N) of serum aspartate and alanine transaminase activities, and to the normal value of alkaline phosphatase level, respectively.

LPAC syndrome was suspected when at least one of the following features was present: The onset of biliary pain before the age of 30 years; biliary pain recurring after cholecystectomy; a personal history of acute pancreatitis with unknown etiology; a personal history of pregnancy cholestasis; or a family history of gallstones before the age of 30 years in first-degree relatives.

The diagnosis was made by ultrasound examination when the following findings were detected in the intrahepatic bile ducts: Hyperechoic foci in the form of comet-tail artifacts, microlithiasis, or stones with acoustic shadows.

Radiological features during ultrasound examinations were interpreted and reported by a skilled radiologist who was familiar with LPAC syndrome. All ultrasound examinations were performed using an Aplio 500 ultrasound machine with a 3.5 MHz transducer (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan).

The subjects were systematically reevaluated and asked about their symptoms 6 months after inclusion in the study through an in-person medical appointment or phone call. Follow-up was based on clinical evaluation and not on ultrasound examination. The efficacy of UDCA treatment was defined as the complete disappearance or a significant decrease of biliary pain intensity or frequency. Intolerance to UDCA treatment was defined as the occurrence of side effects that required either stopping treatment or lowering dosage. Patients’ adherence to UDCA treatment was considered “good” when taking the medication at least six days per week. Adherence was defined as “poor” when patients missed more than one day of medication per week, or if they stopped taking it without having been requested by their physician.

Genetic testing was not performed systematically, but according to the decision of each physician, and written consent was obtained from all patients involved. EDTA whole-blood samples were sent to the genetic laboratory of Saint-Antoine Hospital in Paris. Molecular analysis was performed by sequencing the coding exons and the adjacent intron junctions of all the genes implicated in hereditary cholelithiasis. These genes were ABCB4/MDR3 (NM_00043), ABCB11/BSEP (NM_003742), ATP8B1/FIC1 (NM_005603), ABCC2/MRP2 (NM_000392), NR1H4/FXR (NM_005123), ABCG5/ABCG5 (NM_022436), ABCG8/ABCG8 (NM_022437), SLC4A2/AE2 (NM_003040), GPBAR1/TGR5 (NM_001077191), and AQP8 (NM_001169). DNA was amplified with primers specific for the coding exons and their intron boundaries. Sequencing was performed by capture (NimbleGen; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and next-generation sequencing (MiSeq; Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States), and the results were analyzed with SOPHiA DMM software (SOPHiA Genetics, Boston, MA, United States). When gene variants were detected, results were confirmed on polymerase chain reaction products using the Sanger sequencing technique.

Quantitative variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and qualitative variables were expressed as n (%).

Twenty-four patients prospectively seen in the two hospitals between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018 had both clinical and radiological signs of LPAC syndrome, met none of the exclusion criteria, and were thus included in the study. The characteristics of the 24 patients are presented in Table 1.

| General characteristics | |||

| Median age (yr) | 37 ± 11.8 | (26–67) | n = 24 |

| Gender: Male | 14 | (58) | n = 24 |

| Median BMI (kg/m2) | 24 ± 4.5 | (18.9–34) | n = 24 |

| Pregnancy at diagnosis | 0 | (0) | n = 10 |

| Ethnicity | n = 24 | ||

| Caucasian | 12 | (50) | |

| Maghrebian | 10 | (42) | |

| Asian | 1 | (4) | |

| Sub-Saharan African | 1 | (4) | |

| Medical history | |||

| Acute pancreatitis | 13 | (54) | n = 24 |

| Cholecystectomy | 10 | (42) | n = 24 |

| Family history of cholelithiasis in first-degree relatives | 7 | (30) | n = 23 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 3 | (13) | n = 24 |

| Acute cholangitis | 3 | (13) | n = 24 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 0 | (0) | n = 24 |

| Cholestasis of pregnancy | 0 | (0) | n = 10 |

| Estrogen therapy | 0 | (0) | n = 10 |

| Existing medical conditions | |||

| Recurring pain | 21 | (88) | n = 24 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 9 | (38) | n = 24 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 2 | (14) | n = 14 |

| Acute cholangitis | 1 | (4) | n = 24 |

| Cytolysis | n = 23 | ||

| Presence | 13 | (57) | |

| Quantification (N) | 2.8 ± 3.1 | (0–10) | |

| Cholestasis | n = 23 | ||

| Presence | 13 | (57) | |

| Quantification (N) | 1.7 ± 2.0 | (0–8) | |

Patients with LPAC syndrome were for the most part young with a median age of 37 years, mostly male (58%), and not overweight [median body mass index (BMI) was 24]. Many had a medical history of acute pancreatitis (54%) and cholecystectomy (42%). Interestingly, a family history of gallstones in first-degree relatives was frequent (30%). None of the female patients were pregnant, had a history of cholestasis of pregnancy, or were treated by estrogen therapy.

LPAC syndrome was identified primarily in patients who experienced recurring biliary pain (88%). Only three patients (12%) had no symptoms (they had an ultrasound examination due to a family history of LPAC syndrome). Acute pancreatitis was the most frequent complication that led to the identification of the disease, occurring in nine cases (38%) vs two cases (14%) of acute cholecystitis and only one case (4%) of acute cholangitis. Liver function was not altered; we observed cytolysis and cholestasis in 13 patients (57%). When present, cytolysis and cholestasis were not severe (2.8N and 1.7N, respectively) and disappeared quickly, as only four of 19 patients (21%) still had cytolysis and cholestasis when the ultrasound examinations were performed.

Genetic testing was performed on seven patients, none of which had a mutation in the ABCB4/MDR3 gene.

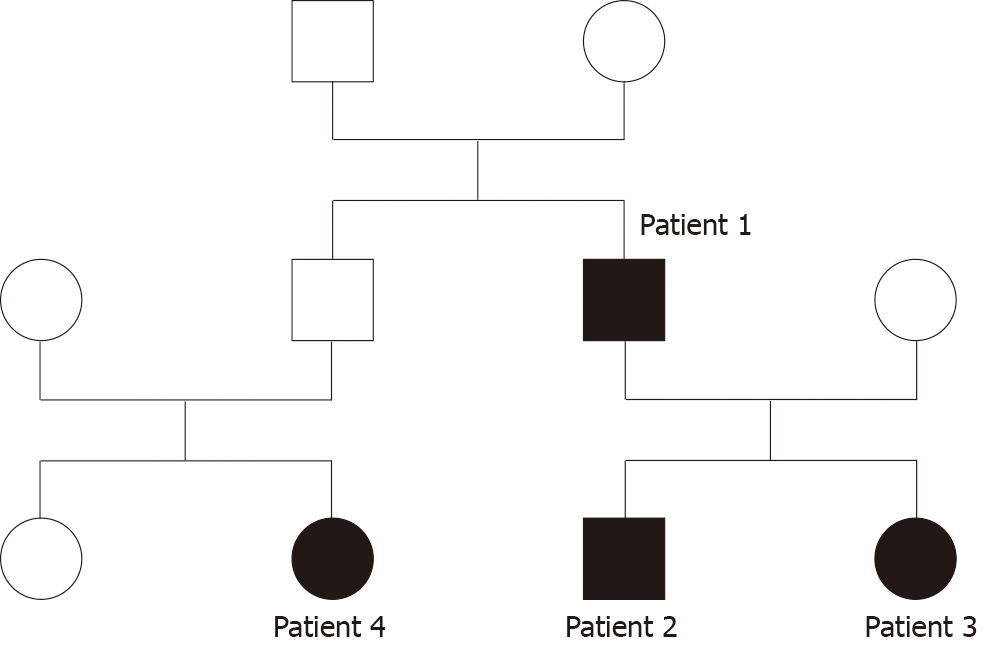

Interestingly, four patients from the same family were diagnosed with LPAC syndrome. Their family tree is presented in Figure 1.

Patient 1 was the father of Patients 2 and 3. He had a medical history of several episodes of acute pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and cholangitis, and underwent cholecystectomy. LPAC syndrome was diagnosed after the occurrence of a new episode of acute pancreatitis. Patients 2 and 3 had no significant medical history or symptoms and underwent ultrasound examinations because of their father’s diagnosis. Patient 4 was the daughter of Patient 1’s brother. She complained of recurring biliary pain and the diagnosis was made by echography. An ultrasound examination was not performed on Patient 4’s father; therefore, we cannot know if he had LPAC syndrome.

Genetic testing was only performed on Patient 1 who had a heterozygous missense variant c.634G>A, p.Ala212Thr in the AQP8 gene. This mutation is not responsible for LPAC syndrome, but it can increase the risk of developing biliary lithiasis.

The diagnosis of LPAC syndrome was made by ultrasound examination performed by an experienced radiologist. The most frequent findings in intrahepatic bile ducts were comet-tail artifacts in 23 patients (96%), microlithiasis in 20 patients (83%), and acoustic shadows in 17 patients (71%). Stones were present only in three patients (13%). Some of the ultrasound findings are presented in Figure 2.

Among patients who had no history of cholecystectomy, gallstones were detected in six (43%), and gallbladder sludge was found in two (14%). Other associated findings were less frequent. The detailed results of the ultrasound examinations are presented in Table 2.

| Intrahepatic bile duct findings | n = 24 | ||

| Comet-tail artifacts | 23 | (96) | |

| Microlithiasis | 20 | (83) | |

| Acoustic shadows | 17 | (71) | |

| Stones | 3 | (13) | |

| Associated findings | |||

| Gallstones | 6 | (43) | n = 14 |

| Gallbladder sludge | 2 | (14) | n = 14 |

| Gallbladder hydrops | 1 | (7) | n = 14 |

| Common bile duct stones | 1 | (4) | n = 23 |

Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) were performed on 15 and three patients, respectively, but microlithiasis was not detected.

The mean follow-up time was 19.7 mo. Complications of LPAC syndrome required hospitalizing 18 patients (75%) in a conventional care unit for a mean duration of 6.8 days. No patients needed to be hospitalized in an intensive care unit. Treatment with UDCA was administered to 18 patients (75%). Among the six patients who were not treated, three were asymptomatic and three refused to take the medication. Twelve patients’ (67%) adherence to UDCA treatment was considered “good.” Five patients (36%) underwent cholecystectomy (three of them were treated both by UDCA and cholecystectomy). None of the 24 patients had to undergo a Roux-en-Y procedure. These results are presented in Table 3.

| Follow-up time (mo) | 19.7 ± 5.8 | (10.1–29.4) | n = 24 |

| Patients’ care | |||

| Hospitalization | |||

| In a conventional care unit | |||

| Yes | 18 | (75) | n = 24 |

| Duration (days) | 6.8 ± 3.1 | (2–14) | n = 18 |

| In an intensive care unit | 0 | (0) | n = 24 |

| Treatment | |||

| UDCA | 18 | (75) | n = 24 |

| Cholecystectomy | 5 | (36) | n = 14 |

| Outcome | |||

| Good adherence to UDCA | 12 | (67) | n = 18 |

| UDCA efficacy | 17 | (94) | n = 18 |

| Onset of action (in weeks) | 3.4 ± 2.5 | (2–12) | n = 17 |

| Pain recurrence | 5 | (28) | n = 18 |

| UDCA intolerance | 2 | (11) | n = 18 |

| Death | 0 | (0) | n = 24 |

Treatment with UDCA was effective in 17 patients (94%). The onset of action was rapid (3.4 wk), and UDCA was well-tolerated: e.g., only two patients (11%) experienced side effects (nausea and diarrhea) which required lowering their dosage. No patients experienced side effects strong enough to completely stop the treatment. Despite UDCA efficacy, biliary pain recurred in five patients (28%), three of whom adhered well to treatment guidelines. Interestingly, among these five patients, four had a genetic susceptibility that could contribute to the recurrence of symptoms. These genetic mutations were not identified as those responsible for LPAC syndrome but could be responsible for genetic cholelithiasis and pancreatitis. Each of the four patients had one of the following mutations: A heterozygous mutation in the gene ATP8B1, a homozygous missense mutation in the gene ABCB11/BSEP, a double heterozygous mutation ΔF508/L967S in the CFTR gene, and a heterozygous missense variant c.3220A>G, p.N1074D in the CASR gene.

No patients died.

Our original study prospectively evaluated 24 patients with LPAC syndrome. Our work determined not only the patients’ characteristics, but also the symptoms and clinical signs that should lead physicians to search for the syndrome, the radiological features essential for diagnosis, and the treatment outcome.

Two limitations in our study should be highlighted: i.e., the relatively limited number of patients included and the fact that genetic testing was not performed systematically, which hinders the analysis of all possible mutations present.

The prevalence of LPAC syndrome has not been described precisely in the literature, but it seems to be more frequent in our study than previously expected, with 24 patients diagnosed in less than 2 years at two medium-size hospitals. Contrary to “common” cholelithiasis, whose risk factors include being older, overweight, or female[6], LPAC syndrome affects young patients with normal BMI. Even if most patients in our study were male (58%), the literature shows that the syndrome seems to occur more frequently among female patients, with a sex ratio close to 3:1[1,3,5,7]. In a study conducted by Condat et al[8], LPAC syndrome was responsible for 22% of cholelithiasis among women younger than 30 years old. In the same study, the average age of female patients was 24.7 years, which is younger than the average age observed among males (between 38 to 40 years in our study and in the literature)[1,5]. Moreover, a previous study showed that the syndrome was associated with a history of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy[8]. These results could be explained by the aggravating role of estrogen that inhibits phospholipid excretion into bile[9]. As LPAC syndrome is associated with particular genetic mutations, suspicion of the disease is strengthened in the case of a family history of cholelithiasis (evident in 30% of the patients in our study).

Most patients are symptomatic with typical biliary pain leading to cholecystectomy in 90% of cases[3]. The recurrence of symptomatology after cholecystectomy is due to intrahepatic lithiasis or lithiasis migration. Acute pancreatitis is a frequent complication of LPAC syndrome, as shown by the fact that nearly half of our patients had a personal history of acute pancreatitis or cholecystectomy, and more than one-third were diagnosed following a new episode of acute pancreatitis. Other complications such as acute cholecystitis and acute cholangitis are less frequent because most patients have already undergone cholecystectomy.

Ultrasound examination is of critical importance in the positive diagnosis of LPAC syndrome and must be carried out and interpreted by a radiologist familiar with the disease. The detection rate of signs of LPAC syndrome ranges from 5% if the radiologist is not familiar with the disease to 90% for an experienced radiologist[10]. Comet-tail artifacts are the most common findings and must be distinguished from pneumobilia (contrary to pneumobilia, comet-tail artifacts are not mobile[2]). CT scans are inefficient for diagnosis because their ability to detect microlithiasis is lower than that of echography. Biliary MRIs are usually normal[10]. Other investigations such as echoendoscopy or liver biopsy are not relevant[11] and an analysis of bile composition to detect low phospholipid concentration cannot be performed in clinical practice[3].

LPAC syndrome is associated with mutations of the ABCB4 gene located on chromosome 7, locus 21 (7q21), which codes for protein MDR3[1,3]. Nevertheless, as diagnosis is based on clinical and radiological criteria, we chose not to systematically perform genetic testing in our study. Moreover, in the literature, mutations were detected in only 50%–65% of the patients suffering from LPAC syndrome[2,3,7,12]. Hypotheses to explain the low mutation detection rate could be the presence of mutations in the introns, mutations in a gene promoter, mutations in a regulatory region, or mutations of another gene or biliary carrier (ABCB11 or BSEP, ABCC2, ABCG5/ABCG8)[2,3,7,13]. Nevertheless, genetic testing can be recommended in some situations. Searching for mutations in first-degree relatives can be done as genetic family counseling with a family screening. For research purposes, searching for mutations of the ABCB4 gene should facilitate detection of new mechanisms responsible for the syndrome and render genetic screening more effective[3,7,8,10].

The incidence of long-term complications, such as cirrhosis or malignant transformation, is still unknown, but sporadic cases have been described in the literature. Chronic aggression of the bile epithelium by lithiasis and hydrophobic bile acids can lead to the chronic inflammation responsible for secondary biliary cirrhosis[3,7,14,15] and secondary sclerosis cholangitis[4,16]. Moreover, dysplasia can ensue from chronic inflammation and cases of cholangiocarcinoma have been described among patients with LPAC syndrome[2,7,12,16-18].

Medical treatment with UDCA is effective and has a rapid and positive impact on symptomatology (94% efficacy with an average onset of action of 3.4 weeks in our study). This observation suggests that symptoms are not directly related to stones, but may be due to inflammation of intrahepatic bile ducts or to cholesterol crystals not detected by echography[2]. UDCA is usually well tolerated and side effects, such as diarrhea and nausea, are rare. Recommended daily dosage varies from 7 to 10 mg/kg, but can be increased to 20 mg/kg if biliary symptoms persist[1,2,7]. UDCA is a long-term treatment that should be continued even if all symptoms have disappeared. There are no recommendations about dietary regimens, but in the case of associated hypercholesterolemia, treatment with statin is preferable to fibrate because the latter increases bile lithogenicity[2,3]. However, the appropriateness of surgical treatment is not clearly determined. In our study, we performed cholecystectomy in one-third of patients in addition to UDCA. The absence of guidelines about the role of cholecystectomy as a treatment for LPAC syndrome is mainly due to the difficulty of determining whether the symptomatology is ascribed to gallbladder lithiasis or to intrahepatic damage[2,3]. Hence, one of the options is to reserve cholecystectomy in case of acute cholecystitis or if treatment with UDCA fails[10]. If performed, cholecystectomy should always be done in addition to medical treatment with UDCA. If done without UDCA treatment, symptoms reoccur in half of patients[1].

In conclusion, LPAC syndrome is likely underreported due to a lack of testing resulting from insufficient awareness among physicians, radiologists, and digestive surgeons. A deeper understanding of this disease by these medical professionals is necessary to avoid overlooking its rather simple diagnosis. LPAC syndrome typically manifests through biliary symptoms or episodes of acute pancreatitis in young patients with normal BMI. Symptoms often reoccur after cholecystectomy and patients usually have family history of cholelithiasis. The diagnosis is made via ultrasound examination by detecting intrahepatic lithiasis or comet-tail artifacts. Other exams are not necessary unless ultrasound examination proves ineffective. Genetic testing is not necessary for diagnosis because no mutations are detected in half of patients, but it can be performed for the purpose of research or genetic family counseling. LPAC syndrome is easily treatable with UDCA, which is rapidly effective, well-tolerated, and avoids the recurrence of biliary symptoms and long-term complications. Cholecystectomy should be reserved in the case of acute cholecystitis or if treatment with UDCA fails. LPAC syndrome is easy to diagnose and treat; therefore, it should no longer be overlooked. To increase its detection rate, all patients who experience recurrent biliary symptoms following an episode of acute pancreatitis should undergo an ultrasound examination performed by a radiologist with knowledge of the disease.

Low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis (LPAC) syndrome is a very particular form of biliary lithiasis with no excess of cholesterol secretion into bile, but a decrease in phosphatidylcholine secretion, which is responsible for stones forming not only in the gallbladder, but also in the liver. This study describes the clinical and radiological characteristics of patients with LPAC syndrome to better identify and diagnose the disease.

LPAC syndrome is considered a rare disease, but it may be underreported due to a lack of testing resulting from insufficient awareness among physicians, radiologists, and digestive surgeons. Improving the understanding of this syndrome will facilitate the screening and treatment of patients.

We aimed to determine the clinical and radiological characteristics, as well as the outcome of patients with LPAC syndrome in order to better identify and diagnose the disease.

We prospectively evaluated all adult patients who were consulted or hospitalized in two hospitals in Paris, France, between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018. All patients whose profiles led to a clinical suspicion of LPAC syndrome underwent a liver ultrasound examination performed by an experienced radiologist to confirm the diagnosis of LPAC syndrome. Twenty-four patients were selected. Patients’ characteristics, radiological features and outcomes were analyzed.

Most patients were young (median age of 37 years), male (58%), and not overweight (median body mass index was 24). Many had a personal history of acute pancreatitis (54%) or cholecystectomy (42%), and a family history of gallstones in first-degree relatives (30%). LPAC syndrome was identified primarily in patients with recurring biliary pain (88%) or after a new episode of acute pancreatitis (38%). When present, cytolysis and cholestasis were not severe and disappeared quickly. Interestingly, four patients from the same family were diagnosed with LPAC syndrome. At ultrasound examination, the most frequent findings in intrahepatic bile ducts were comet-tail artifacts (96%), microlithiasis (83%), and acoustic shadows (71%). Computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging were performed on 15 and three patients, respectively, but microlithiasis was not detected. Complications of LPAC syndrome required hospitalizing 18 patients (75%) in a conventional care unit for a mean duration of 6.8 d. None of them died. Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was effective and well-tolerated in almost all patients (94%) with a rapid onset of action (3.4 wk). Twelve patients’ (67%) adherence to UDCA treatment was considered “good.” Five patients (36%) underwent cholecystectomy (three of them were treated both by UDCA and cholecystectomy). Despite UDCA efficacy, biliary pain recurred in five patients (28%), three of whom adhered well to treatment guidelines.

LPAC syndrome is easy to diagnose and treat; therefore, it should no longer be overlooked. LPAC syndrome typically manifests through biliary symptoms or episodes of acute pancreatitis in young patients with normal BMI. Symptoms often reoccur after cholecystectomy and patients usually have family history of cholelithiasis. The diagnosis is made via ultrasound examination by detecting intrahepatic lithiasis or comet-tail artifacts. Other exams are not necessary unless ultrasound examination proves ineffective. Genetic testing is not necessary for diagnosis because no mutations are detected in half of patients, but it can be performed for the purpose of research or genetic family counseling. LPAC syndrome is easily treatable with UDCA, which is rapidly effective, well-tolerated, and avoids the recurrence of biliary symptoms and long-term complications. Cholecystectomy should be reserved in the case of acute cholecystitis or if treatment with UDCA fails.

LPAC syndrome is likely underreported due to a lack of testing resulting from insufficient awareness among physicians, radiologists, and digestive surgeons. A deeper understanding of this disease by these medical professionals is necessary to avoid overlooking its rather simple diagnosis. To increase its detection rate, all patients who experience recurrent biliary symptoms following an episode of acute pancreatitis should undergo an ultrasound examination performed by a radiologist with knowledge of the disease.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: France

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gonoi W, Rungsakulkij N, Tannuri U S-Editor: Yang Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Rosmorduc O, Hermelin B, Poupon R. MDR3 gene defect in adults with symptomatic intrahepatic and gallbladder cholesterol cholelithiasis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1459-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Erlinger S. Low phospholipid-associated cholestasis and cholelithiasis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36 Suppl 1:S36-S40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rosmorduc O, Poupon R. Low phospholipid associated cholelithiasis: association with mutation in the MDR3/ABCB4 gene. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Benzimra J, Derhy S, Rosmorduc O, Menu Y, Poupon R, Arrivé L. Hepatobiliary anomalies associated with ABCB4/MDR3 deficiency in adults: a pictorial essay. Insights Imaging. 2013;4:331-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rosmorduc O, Hermelin B, Boelle PY, Parc R, Taboury J, Poupon R. ABCB4 gene mutation-associated cholelithiasis in adults. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:452-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Diehl AK. Symptoms of gallstone disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;6:635-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Poupon R, Rosmorduc O, Boëlle PY, Chrétien Y, Corpechot C, Chazouillères O, Housset C, Barbu V. Genotype-phenotype relationships in the low-phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis syndrome: a study of 156 consecutive patients. Hepatology. 2013;58:1105-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Condat B, Zanditenas D, Barbu V, Hauuy MP, Parfait B, El Naggar A, Collot V, Bonnet J, Ngo Y, Maftouh A, Dugué L, Balian C, Charlier A, Blazquez M, Rosmorduc O. Prevalence of low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis in young female patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:915-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Okolicsanyi L, Lirussi F, Strazzabosco M, Jemmolo RM, Orlando R, Nassuato G, Muraca M, Crepaldi G. The effect of drugs on bile flow and composition. An overview. Drugs. 1986;31:430-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Condat B. Le syndrome LPAC (Low Phospholipid-Associated Cholelithiasis) : mythe ou réalité ? FMC-HE, POST’U 2016, Paris. Available from: https://www.fmcgastro.org/textes-postus/no-postu_year/le-syndrome-lpac-low-phospholipid-associated-cholelithiasis-mythe-ou-realite/. |

| 11. | Goubault P, Brunel T, Rode A, Bancel B, Mohkam K, Mabrut JY. Low-Phospholipid Associated Cholelithiasis (LPAC) syndrome: A synthetic review. J Visc Surg. 2019;156:319-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Erlinger S. [Right upper quadrant abdominal pain and fever. Genetic phospholipid deficiency]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:F50-F55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dröge C, Bonus M, Baumann U, Klindt C, Lainka E, Kathemann S, Brinkert F, Grabhorn E, Pfister ED, Wenning D, Fichtner A, Gotthardt DN, Weiss KH, McKiernan P, Puri RD, Verma IC, Kluge S, Gohlke H, Schmitt L, Kubitz R, Häussinger D, Keitel V. Sequencing of FIC1, BSEP and MDR3 in a large cohort of patients with cholestasis revealed a high number of different genetic variants. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1253-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Degiorgio D, Crosignani A, Colombo C, Bordo D, Zuin M, Vassallo E, Syrén ML, Coviello DA, Battezzati PM. ABCB4 mutations in adult patients with cholestatic liver disease: impact and phenotypic expression. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:271-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Denk GU, Bikker H, Lekanne Dit Deprez RH, Terpstra V, van der Loos C, Beuers U, Rust C, Pusl T. ABCB4 deficiency: A family saga of early onset cholelithiasis, sclerosing cholangitis and cirrhosis and a novel mutation in the ABCB4 gene. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:937-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wendum D. [Liver disease associated with hereditary defects of hepatobiliary transporters]. Ann Pathol. 2010;30:426-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tougeron D, Fotsing G, Barbu V, Beauchant M. ABCB4/MDR3 gene mutations and cholangiocarcinomas. J Hepatol. 2012;57:467-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Khabou B, Trigui A, Boudawara TS, Keskes L, Kamoun H, Barbu V, Fakhfakh F. A homozygous ABCB4 mutation causing an LPAC syndrome evolves into cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;495:598-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |