Published online Jun 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i6.277

Peer-review started: February 9, 2020

First decision: March 18, 2020

Revised: April 7, 2020

Accepted: May 5, 2020

Article in press: May 5, 2020

Published online: June 27, 2020

Processing time: 139 Days and 11.9 Hours

Delta hepatitis is a rare infection with an aggressive disease course. For almost three decades, however, there have been no epidemiological studies in our traditionally endemic area.

To investigate the prevalence of delta hepatitis in a sample of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection followed at a Hepatology Unit in Valencia, Spain.

Retrospective evaluation of anti-hepatitis D virus-immunoglobulin G seroprevalence among patients with chronic HBV infection (n = 605) followed at a reference Hepatology Unit in Spain.

The prevalence of anti-hepatitis D virus-immunoglobulin G among HBV-infected patients was 11.5%: Male (63%) and median age of 52 years. The majority were born in Spain (67%) and primarily infected through intravenous drug use. However, a significant percent (24.5%), particularly those diagnosed in more recent years, were migrants presumably nosocomially infected. Comorbidities such as diabetes (8.5%), obesity/overweight (55%), and alcohol consumption (34%) were frequent. A high proportion of patients developed liver complications such as cirrhosis (77%), liver decompensation (81%), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (16.5%), or required liver transplantation (LT) (59.5%). Diabetes was associated with progression to cirrhosis, LT, and death. Male sex, increasing age, and alcohol were associated with LT and HCC. Compared to HBV mono-infected patients, delta individuals developed cirrhosis and liver decompensation more frequently, with no differences in HCC rates.

Patients infected in the 1980’s were mostly locals infected through intravenous drug use, whereas those diagnosed recently are frequently non-Spanish natives from endemic areas. Regardless of their origin, patients are predominantly male with significant comorbidities, which potentially play a major role in disease progression. We confirm a high rate of subsequent liver complications.

Core tip: Our study shows that there has been a change in the delta hepatitis virus-infected patient profile in our unit. Most patients infected in the 1980s, due to intravenous drug abuse, have progressed to cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma and therefore still represent a significant burden on our Hepatology Unit. However, our main concern is with newly diagnosed patients, as there is a clear delay in the diagnosis of infection and cirrhosis. In addition, follow-up in their home countries has been poor. Most of them come from Eastern Europe and prior medical intervention was the main route of infection. We must also take into account the presence of comorbidities, e.g., metabolic syndrome and alcohol intake, which may contribute to the aggressive progression of the disease. Therefore, we must devote our efforts to controlling these aspects and finding an effective treatment, given the poor results offered by pegylated-α-interferon.

- Citation: Hernàndez-Èvole H, Briz-Redón Á, Berenguer M. Changing delta hepatitis patient profile: A single center experience in Valencia region, Spain. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(6): 277-287

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i6/277.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i6.277

Delta hepatitis is a rare infectious disease caused by hepatitis D virus (HDV), an RNA defective virus that requires the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) to infect cells. Roughly 15 million people are infected worldwide. However, there are areas where the prevalence is higher, such as the Mediterranean basin[1].

The importance of early detection of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-HDV coinfection is due to the aggressive course of the disease demonstrated in these patients compared to those only infected by HBV. At present, the only treatment available and recommended by Scientific Societies is alfa pegylated interferon[2]. However, its use is restricted to highly selected patients (avoided in cirrhosis, active autoimmune disease and certain psychiatry disorders) and the response rate is low. Consequently, the only possible and effective way to control the spread of the infection currently is HBV vaccination.

In 1988, Buti et al[3] reported a delta seroprevalence among HBV carriers of 15% in Spain; highlighting that intravenous drug users (IDUs) were the major risk group. Most recent studies from northern Spain, a non-traditional immigration area, have reported decreasing rates of infection over a 29-year period. A similar pattern has been documented in other European countries. The prevalence stabilized in the 1990s but was followed by a subsequent increase from 4.7% in 2003-2007 (lowest prevalence) to 7.4% in 2008-2012[4].

There are no recent epidemiological data for our area, particularly information regarding the current profile of HDV infected patients. This information is especially needed given that the region is an immigration receiving area and the absence of epidemiological information for almost three decades.

Based on this background, we aimed to update the epidemiological data on HDV infection in our geographical area. We specifically aimed to assess whether there had been changes in the profile of infected individuals, confirm the greater aggressive nature of HDV-HBV coinfection compared to HBV mono-infection, and describe risk factors for progression of disease.

A retrospective single center study review of a database of HBV-infected patients followed in the Hepatology Unit of the Hospital Universitari I Politècnic “La Fe” (HUP La Fe). Inclusion criteria were: Diagnosis of delta hepatitis (confirmed by the presence of anti-HDV-immunoglobulin G [IgG]). No exclusion criteria were set.

The following data were extracted from the chart review: (1) Demographics including age, sex, country of birth, race, year of diagnosis, and first visit to the Unit, and probable mechanism of acquisition of HBV-HDV infection; (2) Presence of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and alcohol intake, history of infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); and (3) Hepatitis B e (HBe) antigen as well as alanine aminotransferase at diagnosis or first visit. In addition, the presence and time of occurrence of cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The date a patient may have received a transplant or died was also recorded. The follow-up ended at the time of liver transplantation (LT), death or in the absence of these events, at the last visit.

The second part of the research was focused on the differences in disease evolution between HBV-HDV co-infected patients vs the HBV mono-infected patients. For this purpose, we designed a case-control study (1:1 match): HBV-infected patients to HBV-HDV-infected patients controlling for the year of diagnosis and sex. The following data were extracted: Presence of HCV or HIV coinfection, cirrhosis, liver decompensation, and liver cancer as well as laboratory tests gathered from the first visit onward including serum creatinine (mg/dL), estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2), total bilirubin (mg/dL), albumin (g/dL), platelets (mm3), international normalized ratio, Child-Turcotte-Pugh, and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease staging.

HDV infection was defined as the presence of anti-HDV-IgG in patient serum. Chronic HBV infection was confirmed with the presence of HBsAg antigen in serum over a 6 mo period. Coinfection by HCV or HIV was confirmed with the presence of anti-HCV-IgG and anti-HIV-IgG, respectively. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on histologic, elastographic (liver stiffness greater than 12.5 kPas), and/or a composite of laboratory/imaging criteria[5].

Continuous variables are expressed as the median and interquartile range, while categorical variables are depicted by the number and corresponding percentage. The comparison of qualitative variables was performed with χ2 or Fisher’s test. For the analysis of continuous variables with a normal distribution, the Student’s t-test was used while the Mann-Whitney test was used for variables not following a normal distribution. The statistical significance was set at 0.05. To clarify the role of HDV coinfection in the development of the outcomes during the course of the disease previously mentioned, Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were done and the cumulative risk of developing these events was analyzed with Cox regression. All statistical tests performed for the analysis/comparison of variables excluded missing data. Particularly, patients missing one of the dates needed for the computation of a certain survival time outcome (depending on the risk being evaluated) were excluded for the estimation of the corresponding Kaplan-Meier curve.

The statistical analysis was performed using an SPSS program version 24.0 (IBM corporation). The R packages survival[6] and survminer[7] were used to produce the survival curves.

The study protocol coded MBH-INT-2018-01 was examined and approved by the Ethics Committee of HUP “La Fe”.

A total of 605 HBV-infected patients were included. Delta serology had not been tested in three cases. Seventy (n = 70) patients were anti-HDV-IgG positive (11.57%).

The general characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Patients were predominantly male (62.9%) and born in Spain (67.1%) with a median age of 52 years (interquartile range 12) at study entry. A non-negligible proportion (24.3%) were migrants from Eastern European countries. Regarding the route of infection, virtually half of the patients (45.7%) did not remember the possible source of the infection. Of the remaining patients 20% had a probable iatrogenic source of infection and (14.9%) had history of IDU.

| Demographic parameters | n (%) | Missing data, % | |

| Sex, men | 44 (62.9) | 0 | |

| Country of birth by region | 0 | ||

| Spain | 47 (67.1) | ||

| Eastern Europe | 17 (24.3) | ||

| Other | 6 (8.6) | ||

| Probable route of infection | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 32 (45.7) | ||

| Iatrogenesis | 14 (20.9) | ||

| Intravenous drug use | 10 (14.9) | ||

| Household contact | 6 (8.6) | ||

| Sexual intercourse | 4 (5.7) | ||

| Blood transfusion | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Other | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Non-diabetic | 64 (91.4) | 0 |

| Alcohol consumption | 24 (34.3) | 1.42 | |

| Weight | 8.7 | ||

| Underweight | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Normal weight | 26 (37.1) | ||

| Overweight | 23 (32.9) | ||

| Obese | 12 (17.2) | ||

| Serologic parameters | |||

| HBe antigen | HBeAg+ | 8 (11.4) | 1.4 |

| HIV | Anti-HIV-IgG + | 7 (10) | 5.7 |

| HCV | Anti-HCV-IgG + | 8 (11.4) | 0 |

| Events | |||

| Progression to cirrhosis | 54 (77.1) | 1.4 | |

| Liver decompensation | 39 (72.2) | 7.4 | |

| Most frequent type of liver decompensation | |||

| Ascites | 27 (71.1) | ||

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 10 (26.3) | ||

| Liver encephalopathy | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 0 (0) | ||

| Liver cancer | 9 (12.9) | 0 | |

| Liver transplant | 32 (45.7) | 0 | |

| Death | 4 (5.7) | 0 | |

Although no patient was initially diabetic, diabetes developed over the course of the disease in a small proportion of individuals (8.6%). Furthermore, 55.5% were either obese or overweight with a median body mass index of 25.5 kg/m2. Alcohol consumption was reported by roughly one-third of the sample (34.1%). Regarding coinfection with other viruses, 10.6% (n = 7) and 11.4% (n = 8) were HIV and HCV coinfected, respectively. In most cases, coinfections occurred in Spanish patients with a history of IDU, infected during the peak incidence in the 1980s. Only 11.6% were HBe-antigen positive at diagnosis or first visit to the Unit. The majority (58.6%) of patients had alanine aminotransferase levels 1.5 times the upper limit of normality at diagnosis or first visit to the unit.

One-third of the population (31.4%) had received pegylated interferon alfa therapy at some point in the disease course, with none responding. None of the patients was on interferon treatment at the time of the study. Early treatment discontinuation due to adverse events occurred in 20% of those treated. In contrast to delta therapy, antivirals against HBV were frequently used, with 54.3% of patients having received oral antivirals at some point during their disease course. Tenofovir was the most frequent antiviral used (36.8%) followed by Lamivudine (28.9%). Fifteen patients had never been treated with either pegylated interferon or oral antivirals.

Either at first visit or during follow-up, a large proportion (77.1%) of patients progressed to cirrhosis. Of these, the majority (80.9%) developed some type of decompensation, particularly ascites (71.1%) or upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to varices (26.3%). HCC developed in 16.9% of patients and liver transplantation was performed in 59.3%. Four patients died in the course of the follow-up, with two of the deaths related to their liver disease. Median age at time death was 50.5 years (interquartile range, 23).

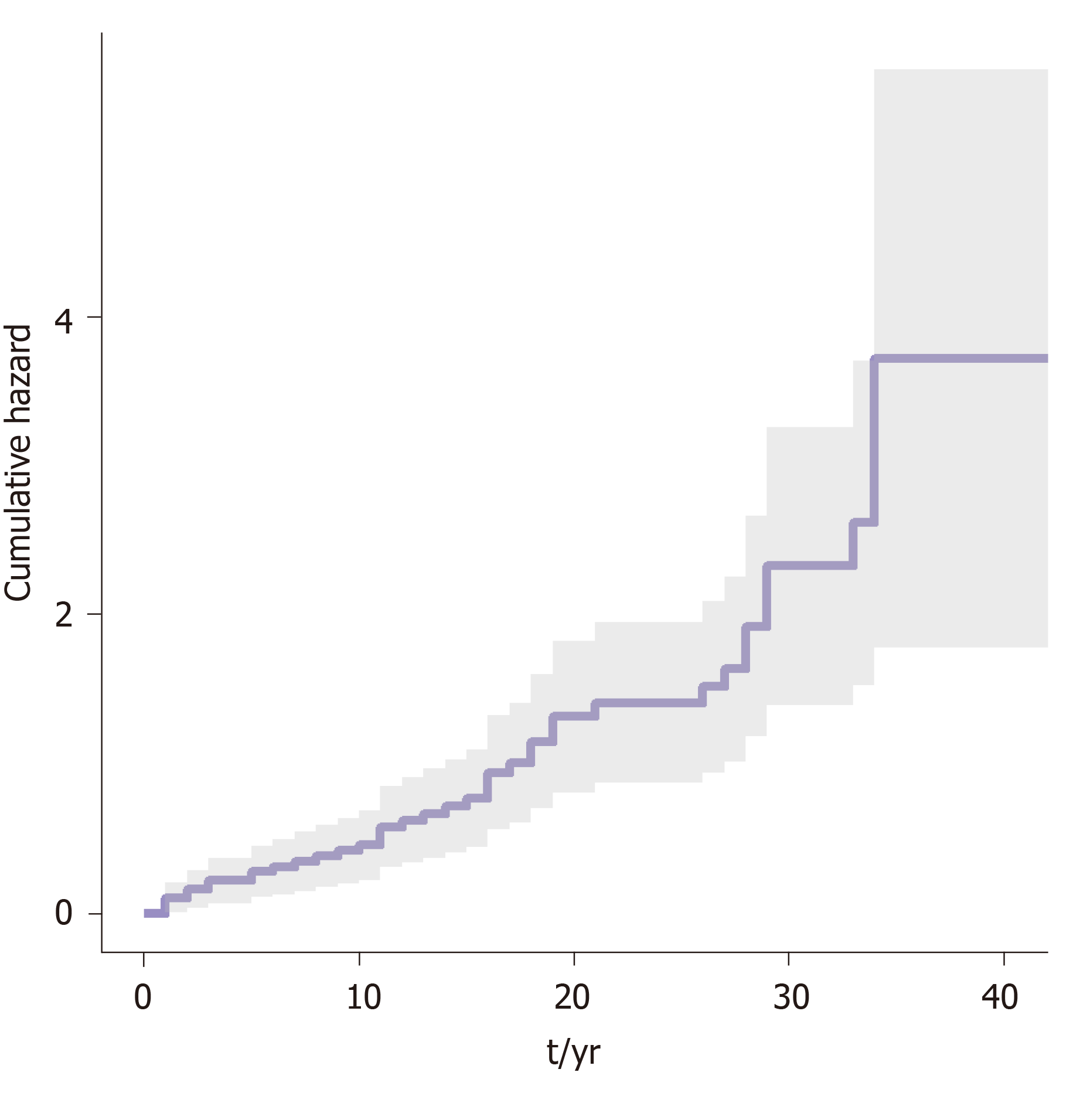

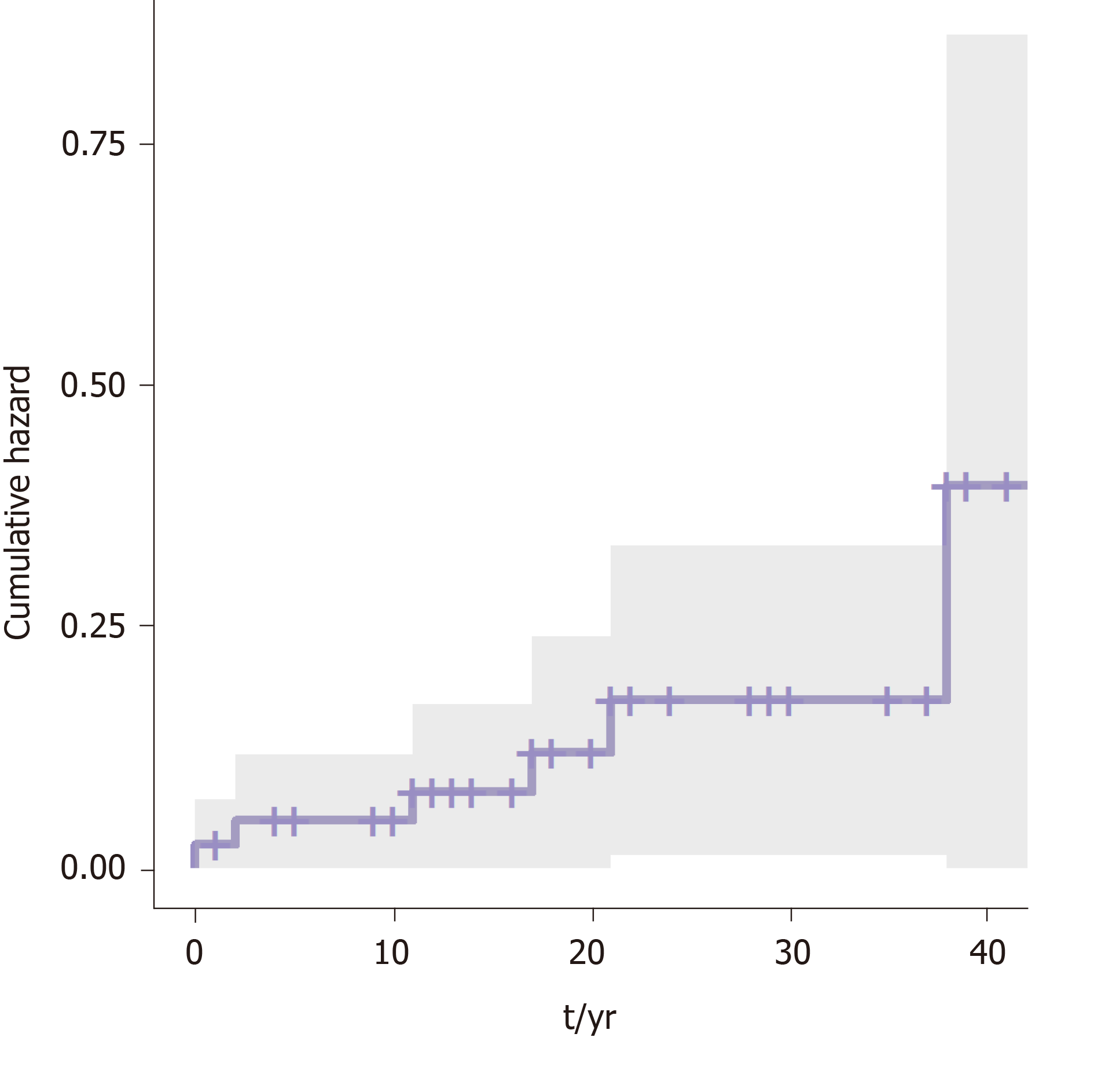

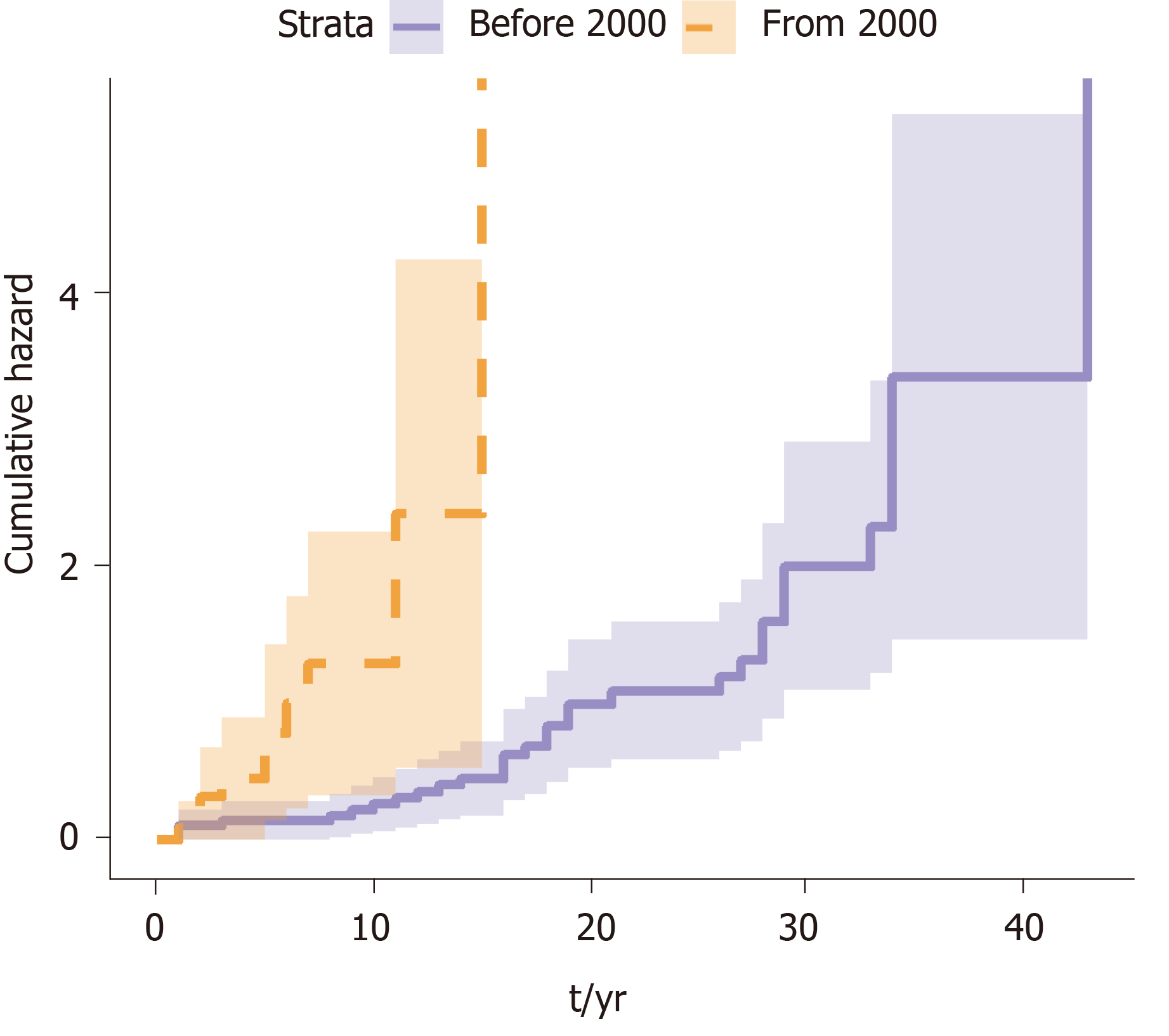

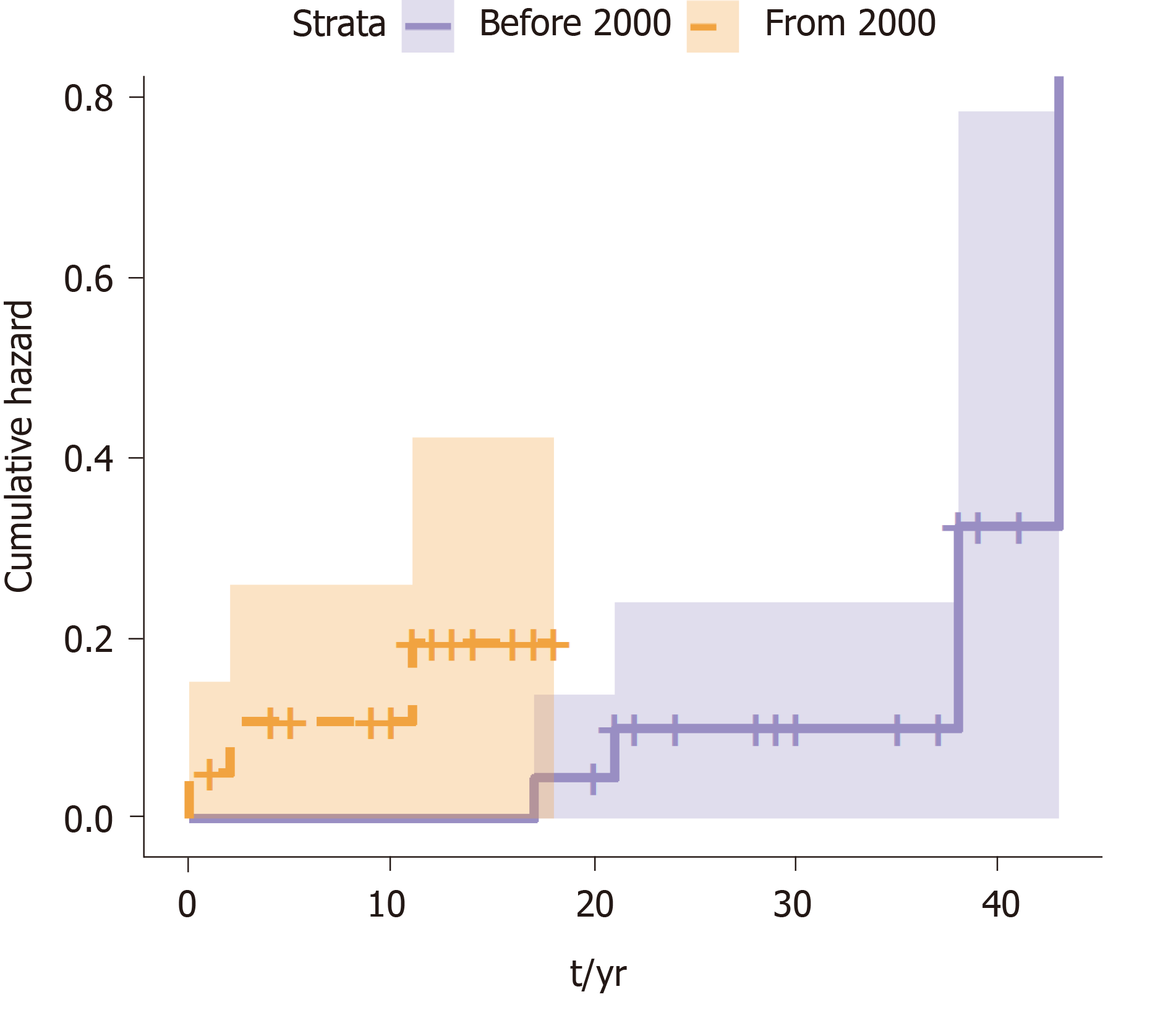

A survival analysis was performed to determine the cumulative risk of developing the different events during follow up (Figure 1 and Figure 2). We differentiated the cumulative risk of developing cirrhosis and liver cancer according to whether they were diagnosed before or from 2000 (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Progression to cirrhosis at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years from diagnosis occurred in 24%, 37%, 54%, and 73% of the patients, respectively. Liver cancer was observed at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years from diagnosis for the 5%, 5%, 8%, and 11%, respectively. In turn, the probability of developing decompensated cirrhosis from diagnosis reached 65%, 76%, 76%, and 88% at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years, respectively. Finally, LT-free mortality at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years from diagnosis was 3%, 3%, 7%, and 12%, respectively.

Factors associated with the development of the different events are shown in Table 2. Diabetes was significantly associated with progression to cirrhosis, LT, and death. Furthermore, men were more frequently transplanted, with LT significantly increasing with patient age. Age was also significantly related to the onset of liver cancer. Alcohol consumption was also found to be associated with the need of LT as well as with liver cancer, but without reaching statistical significance in the latter. Finally, a history of interferon therapy was associated with a higher probability of LT.

| Cirrhosis | Liver cancer | Liver decompensation2 | Transplantation | Survival | |

| Age | + (0.056)2 | ++ (0.007) | NS | ++ (0.034) | NS |

| Sex | NS | NS | + (0.101) | ++ (0.040) | NS |

| Country of birth | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Diabetes | ++ (0.027) | NS | + (0.085) | ++ (0.013) | ++ (0.004) |

| Overweight | NS | NS | NS | + (0.104) | NS |

| Alcohol consumption | NS | + (0.100) | NS | ++ (0.019) | NS |

| HIV coinfection | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| HCV coinfection | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Log [ALT] | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Treatment with IFN | NS | NS | NS | ++ 0.034 | NS |

| Antiviral treatment | + (0.092) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

We compared those patients diagnosed before the year 2000 to those diagnosed after 2000 to the present to assess the impact of changes in the Spanish population due to migration (based on data provided by the Immigration National Survey)[8]. Significant differences were noticed regarding the time from diagnosis of infection to cirrhosis among patients diagnosed before and after the year 2000 (Table 3). The median time interval from diagnosis to cirrhosis was 2 years [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.0-4.1] for those patients seen after the year 2000, while the interval was significantly longer 18.0 years (95%CI: 14.0-22.0); (P < 0.0001) for those patients seen before the year 2000.

| Demographic parameters | Total | Diagnosis before 2000 | Diagnosis after 2000 | P value | |

| Country of birth by region | < 0.00 | ||||

| Spain | 47 (67.1) | 37 (92.5) | 10 (33.3) | ||

| Eastern Europe | 17 (24.3) | 3(7.5) | 14 (46.7) | ||

| Other | 6 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 6 (20) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Diabetic | 6 (8.6) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (16.7) | 0.038 |

| Alcohol consumption | Alcohol consumption | 24 (34.3) | 12 (30) | 12 (41.4) | 0.327 |

| Weight | 0.038 | ||||

| Underweight | 2 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (3.8) | ||

| Normal weight | 26 (37.1) | 12 (32.4) | 14 (53.8) | ||

| Overweight | 23 (32.9) | 14 (37.8) | 9 (34.6) | ||

| Obese | 12 (17.1) | 10 (27) | 2 (7.7) | ||

| Serologic parameters | |||||

| HBe antigen | HBeAg + | 8 (11.4) | 8 (11.4) | 0 (0) | 0.008 |

| HIV | Anti-HIV-IgG + | 7 (10) | 7 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.024 |

| HCV | Anti-HCV-IgG+ | 8 (11.4) | 8 (11.4) | 0 (0) | 0.009 |

| Events | |||||

| Progression to cirrhosis | 54 (77.1) | 33 (82.5) | 21 (72.4) | 0.316 | |

| Liver decompensation | 39 (72.2) | 24 (77.4) | 15 (75) | 0.842 | |

| Liver transplant | 32 (45.7) | 22 (55) | 10 (33.3) | 0.74 | |

| Death | 4 (5.7) | 2 (5) | 2 (6.7) | 0.766 | |

In an attempt to distinguish the effect of delta virus from that of HBV, HDV-HBV patients were paired with HBV-patients of the same sex and diagnosis year. Eventually, 62 HBV patients were included. Mono-infected HBV-patients were also predominantly men with a similar median age of 55.05 years (range: 30-83). Demographic, serological, and evolutive parameters of paired patients are summarized in Table 4. Cirrhosis and liver decompensation developed in a larger proportion of delta patients (P < 0.000). In fact, only 14 of HBV-mono-infected patients progressed to cirrhosis compared to 43 of those coinfected. No differences in HCC development were found between groups.

| HBV patient sample | HDV patient sample | P value | ||

| Demographic parameters | Age in yr | 55.05 | 48.90 | < 0.024 |

| Sex, men | 40 (64.5) | 40 (64.5) | - | |

| Serological parameters | HIV | 0 (0) | 7 (11.9) | < 0.005 |

| HCV | 4 (6.5) | 8 (12.9) | NS | |

| Evolution parameters | Liver cirrhosis | 14 (23.3) | 43 (74.1) | < 0.000 |

| Liver decompensation | 5 (8.2) | 33 (57.9) | ||

| Liver cancer | 4 (6.6) | 5 (8.5) | NS | |

The purpose of this study was to describe the prevalence and profile of the delta hepatitis-infected population in our Hepatology Unit over the last 30 years, and the differences due to migration. We also determined current risk factors associated with an unfavorable course and elucidated compliance with clinical practice guidelines.

The major findings can be summarized as follows. (1) Delta-infected patients were middle-aged males in whom HIV or HCV coinfection existed. Alcohol consumption and overweight-obesity were frequently present. (2) A substantial proportion (40%) was non-Spanish born, particularly those diagnosed more recently. (3) The profile of HDV-infected patients has substantially changed over the years, with a higher prevalence of Spanish-born, more frequently infected through IDU, and consequently more frequently coinfected with either HIV or HCV among those diagnosed before the year 2000. By contrast, in those diagnosed more recently there was a significantly higher proportion of coinfected immigrants, presumably due to nosocomial infection. (4) A significant proportion of patients progressed to cirrhosis and/or HCC, highlighting the aggressive nature of this co-infection. and (5) A relatively high number of patients (31.4%) had never received therapy with pegylated interferon.

Delta hepatitis is a concern in HBV-infected patients in our region. Indeed, the prevalence of HDV infection in our referral area is 11.57%, a rate higher than that previously reported both in our region as well as in surrounding countries. These findings might be due to our institution being a transplantation referral center and the recent migratory pattern. Recent studies in Spain have reported lower prevalence rates. According to Aguilera et al[9], the delta prevalence in a tertiary hospital in Santiago de Compostela in 2018 was 4% among HBsAg+ patients followed since 2000. As in our study, patients diagnosed before 2000 were preferentially Spanish-born males, with a history of prior IDU. In fact, data from several studies have clearly shown that during the 1980 and 1990s, HDV-infected patients were mostly IDUs, with seroprevalence rates in IDUs ranging from 60% (de Miguel et al[10]) to 68% (Castro Iglesias et al[11]). In our region, a prevalence of 50% among IDUs was reported in the 1980s with no infections found among asymptomatic HBsAg+ carriers without a history of drug addiction[12]. In the most recent study from 2017, the prevalence was 8.2% among 1215 patients with chronic HBV infection followed since 1983 in Northern Spain[4]. This study also highlighted a decreasing prevalence among Spanish patients with the migrant population having become the main source of Delta infection nowadays. In addition, they detected an increased number of infections related to sexual practices. In our sample only 4 patients (3 women and 1 men) contracted the virus because of presumably “risky sexual practices,” but they were uniformly distributed between the two groups according to year of diagnosis, before and after 2000. Unfortunately, given the retrospective nature of this study, data on sexual practices were not universally recorded.

As previously reported, a proportion of patients were co-infected with other viruses. HIV (10.6%) and HCV (11.4%)-coinfection was mainly observed in the Spanish population, where the main risk factor was IDU. Interestingly, 5.7% of the sample had quadruple HBV, HDV, HCV, and HIV infection. As typically described in the Mediterranean area, most of the patients were anti-HBe positive at time of diagnosis.

The profile of currently diagnosed HDV-infected patients is that of middle-aged males, migrating from endemic areas, particularly Eastern Europe, where prior medical contact/intervention seems to be the main risk factor for infection. The few studies in our country evaluating the migrant population have solely focused on people from the African continent. López-Vélez et al[13] found that 10% of HBsAg+ asymptomatic carriers from a cohort of sub-Saharan Africa immigrants residing in Madrid were also anti-HDV-IgG-positive. More recent data among immigrants from Equatorial Guinea living in Madrid demonstrated a prevalence of HDV infection of 20.9% of HBsAg carriers[14].

Regarding the natural history of this infection, our data confirmed prior studies highlighting the aggressive course of HBV-HDV coinfected patients. Indeed, three-quarters of patients progressed to cirrhosis and liver decompensation. Furthermore, only 3.3 years elapsed between the diagnosis of compensated cirrhosis and liver transplantation, death or last visit. The lack of response to pegylated interferon as well as the presence of frequent comorbidities, such as diabetes, obesity or alcohol intake may explain these findings. In summary, given the low efficacy rate of interferon, addressing adequately these comorbidities seems the best strategy to improve the long-term outcome of HDV-infected individuals. In addition, it is likely that the very short delay observed between diagnosis and cirrhosis in those diagnosed after the year 2000 may be related to the fact that most of these patients were migrants (46.7%) with no prior liver evaluation.

The main limitation of this study lies in its retrospective design. We cannot exclude selection bias potentially resulting in a prevalence underestimation and errors in estimating the time of infection. Furthermore, as this was a single center study, the sample size was relatively small which may have limited statistical power. Finally, no data on viral load was collected due to substantial missing data in early years and the change in quantitative techniques over time.

Despite these limitations, this research provides epidemiological data in a historically endemic area with new migration, highlighting changes in the patient profile, with a predominance of patients coming from Eastern Europe and the high frequency of comorbidities that may impact disease progression.

In conclusion, 11.5% of our HBV-infected population is coinfected with HDV. Recently, diagnosed patients are non-Spanish born individuals coming from endemic countries where the main risk factor is presumably prior medical contact/intervention, inadequately diagnosed and followed until their arrival to Spain. Importantly, IDU patients infected during the first outbreak in the 1980s still represent a significant burden as most have progressed to cirrhosis and/or liver cancer. Independently from the country of origin, the majority of HDV-infected individuals are men with comorbidities, potentially playing a major role in disease progression. Finally, the low use of pegylated interferon together with its very low efficacy highlights the need for better therapies.

At present, epidemiological data and information regarding possible changes in the infected patient's profile are scarce. In addition, there were no updated epidemiological data in our region for three decades.

To carry out this research in Spain is of special interest given the idiosyncrasies of our country, and especially of our Region, Comunidad Valenciana, as an immigration receiving area.

The main objective was to describe the prevalence and profile of the hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection in our referral hospital. Secondary objectives were as follows: (1) To determine the epidemiology of the HDV infection; (2) To assess risk factors associated with this infection and determine whether the disease course is worse than in hepatitis B virus (HBV) mono-infected patients of the same age and sex; and (3) To elucidate whether the recommendations of the European guidelines for treatment are met.

Retrospective evaluation of anti-HDV-immunoglobulin G seroprevalence among patients with chronic HBV infection followed in a reference Hepatology Unit. Demographic, clinical, analytic, serologic, and virology parameters were retrieved from chart review together with evolution events (cirrhosis, liver decompensation, liver transplantation, and death). HDV-HBV patients were matched 1:1 by age and year of diagnosis to HBV mono-infected patients.

Most of anti-HDV-IgG patients were men (63%) with a median age of 52 years. The majority were Spaniards (67%), who were infected due to intravenous drug use; 24.5% of the population corresponded to migrants, presumably due to a nosocomial infection. Comorbidities (diabetes, alcohol consumption and overweight) were frequent in both groups. A high proportion of patients developed liver complications such as cirrhosis (77%), liver decompensation (81%), or HCC (16.5%), or required liver transplantation (59.5%). Compared to HBV mono-infected patients, delta individuals more frequently developed cirrhosis and liver decompensation, with no differences in HCC rates. The main limitation of this study lies in its retrospective quality. Therefore, we must base our conclusions on the current sample and follow patients prospectively in order to continue updating their data. Future research should collect virological data (HDV viral load) and determine the genotype in order to elucidate the role of these factors and determine if it is possible to ascertain individualized evolutionary courses according to the characteristics previously exposed.

We confirmed our hypothesis that the HDV-infected population has changed starting in 2000 due to an increase in the immigrant population. However, the disease outcomes remain the same: Cirrhosis, impaired liver function and HCC. We have found a high prevalence of delta hepatitis in our area compared to other Spanish and European regions; probably because increased number of immigrants. This implies that we must be very diligent in screening for this infection in order to be able to offer patients early follow-up.

Delta hepatitis remains a major concern and must follow these patients carefully given the significant complications seen on follow-up. Future research should elucidate the behavior of patients diagnosed over the last decade.

We are thankful to the physicians taking care of HDV-infected individuals.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Spain

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good):

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Qi XS, Soldera J, Tajiri K, Zhang XC S-Editor: Yu XQ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Koh C, Heller T, Glenn JS. Pathogenesis of and New Therapies for Hepatitis D. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:461-476.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67:370-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3745] [Cited by in RCA: 3799] [Article Influence: 474.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Buti M, Esteban R, Jardi R, Allende H, Baselga JM, Guardia J. Epidemiology of delta infection in Spain. J Med Virol. 1988;26:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ordieres C, Navascués CA, González-Diéguez ML, Rodríguez M, Cadahía V, Varela M, Rodrigo L, Rodríguez M. Prevalence and epidemiology of hepatitis D among patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a report from Northern Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:277-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ferraioli G, Wong VW, Castera L, Berzigotti A, Sporea I, Dietrich CF, Choi BI, Wilson SR, Kudo M, Barr RG. Liver Ultrasound Elastography: An Update to the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology Guidelines and Recommendations. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018;44:2419-2440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 371] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kassambara A, Kosinski M, Biecek P. Survminer. Drawing Survival Curves using “ggplot2”. R package version 0.3, 1. 2019. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survminer/index.html. |

| 7. | Therneau T. A Package for Survival Analysis in S. version 2.38. 2015. Available from: https://www.mayo.edu/research/documents/tr53pdf/DOC-10027379. |

| 8. | Instituto Nacional de Estadística I. Encuesta Nacional de Inmigración. 2008; 1-8. Available from: http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177005&menu=resultados&idp=1254735573002. |

| 9. | Aguilera A, Trastoy R, odríguez-Calviño J, Manso T, de Mendoza C, Soriano V. Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis delta in patients with chronic hepatitis B in Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:1060-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | de Miguel J, Collazos J, Mayo J, Martinez E, Lopez de Goicoechea MJ. Hepatitis D virus infection in drug addicts infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:363-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Castro Iglesias MA, Pereira Andrade JD, Rodríguez Lozano J, Sánchez Mozo P, Ramírez Cerceda C, Iglesias Gil de Bernabé F. [Epidemiologic and clinical study of infection caused by hepatitis delta virus in the health service area of La Coruna]. Rev Clin Esp. 1989;185:55-59. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Rodrigo JM, Serra MA, Gimeno V, Olmo JA, Aparisi L, Escudero A, Wassel AH, Bixquert M. Prevalence of delta infection in drug addicts in Valencia, Spain. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;234:407-408. [PubMed] |

| 13. | López-Vélez R, Turrientes C, Gutierrez C, Mateos M. Prevalence of hepatitis B, C, and D markers in sub-Saharan African immigrants. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:650-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rivas P, Herrero MD, Poveda E, Madejón A, Treviño A, Gutiérrez M, Ladrón de Guevara C, Lago M, de Mendoza C, Soriano V, Puente S. Hepatitis B, C, and D and HIV infections among immigrants from Equatorial Guinea living in Spain. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:789-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |